Hard disk drive

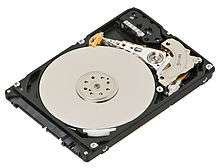

Internals of a 2.5-inch SATA hard disk drive | |

| Date invented | 24 December 1954[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|

| Invented by | IBM team led by Rey Johnson |

| Computer memory types |

|---|

| Volatile |

| RAM |

| Historical |

|

| Non-volatile |

| ROM |

| NVRAM |

| Early stage NVRAM |

| Magnetic |

| Optical |

| In development |

| Historical |

|

A hard disk drive (HDD), hard disk, hard drive, or fixed disk,[lower-alpha 2] is an electromechanical data storage device that uses magnetic storage to store and retrieve digital information using one or more rigid rapidly rotating disks (platters) coated with magnetic material. The platters are paired with magnetic heads, usually arranged on a moving actuator arm, which read and write data to the platter surfaces.[2] Data is accessed in a random-access manner, meaning that individual blocks of data can be stored or retrieved in any order and not only sequentially. HDDs are a type of non-volatile storage, retaining stored data even when powered off.[3][4][5]

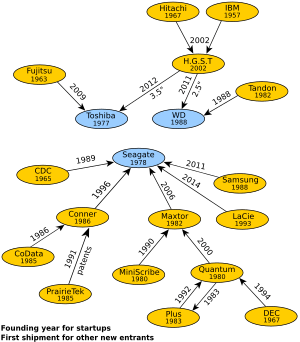

Introduced by IBM in 1956,[6] HDDs became the dominant secondary storage device for general-purpose computers by the early 1960s. Continuously improved, HDDs have maintained this position into the modern era of servers and personal computers. More than 200 companies have produced HDDs historically, though after extensive industry consolidation most units are manufactured by Seagate, Toshiba, and Western Digital. HDDs dominate the volume of storage produced (exabytes per year) for servers. Though production is growing slowly, sales revenues and unit shipments are declining because solid-state drives (SSDs) have higher data-transfer rates, higher areal storage density, better reliability,[7] and much lower latency and access times.[8][9][10][11]

The revenues for SSDs, most of which use NAND, slightly exceed those for HDDs.[12] Though SSDs have nearly 10 times higher cost per bit, they are replacing HDDs where speed, power consumption, small size, and durability are important.[10][11]

The primary characteristics of an HDD are its capacity and performance. Capacity is specified in unit prefixes corresponding to powers of 1000: a 1-terabyte (TB) drive has a capacity of 1,000 gigabytes (GB; where 1 gigabyte = 1 billion bytes). Typically, some of an HDD's capacity is unavailable to the user because it is used by the file system and the computer operating system, and possibly inbuilt redundancy for error correction and recovery. Performance is specified by the time required to move the heads to a track or cylinder (average access time) plus the time it takes for the desired sector to move under the head (average latency, which is a function of the physical rotational speed in revolutions per minute), and finally the speed at which the data is transmitted (data rate).

The two most common form factors for modern HDDs are 3.5-inch, for desktop computers, and 2.5-inch, primarily for laptops. HDDs are connected to systems by standard interface cables such as PATA (Parallel ATA), SATA (Serial ATA), USB or SAS (Serial Attached SCSI) cables.

History

| Parameter | Started with (1957) | Developed to (2017) | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity (formatted) | 3.75 megabytes[13] | 14 terabytes[14] | 3.73-million-to-one[15] |

| Physical volume | 68 cubic feet (1.9 m3)[lower-alpha 3][6] | 2.1 cubic inches (34 cm3)[16][lower-alpha 4] | 56,000-to-one[17] |

| Weight | 2,000 pounds (910 kg)[6] | 2.2 ounces (62 g)[16] | 15,000-to-one[18] |

| Average access time | approx. 600 milliseconds[6] | 2.5 ms to 10 ms; RW RAM dependent | about 200-to-one[19] |

| Price | US$9,200 per megabyte (1961)[20] | US$0.032 per gigabyte by 2015[21] | 300-million-to-one[22] |

| Data density | 2,000 bits per square inch[23] | 1.3 terabits per square inch in 2015[24] | 650-million-to-one[25] |

| Average lifespan | c. 2000 hrs MTBF | c. 2,500,000 hrs (~285 years) MTBF[26] | 1250-to-one[27] |

The first production IBM hard disk drive, the 350 disk storage, shipped in 1957 as a component of the IBM 305 RAMAC system. It was approximately the size of two medium-sized refrigerators and stored five million six-bit characters (3.75 megabytes)[13] on a stack of 50 disks.[28]

In 1962, the IBM 350 was superseded by the IBM 1301 disk storage unit,[29] which consisted of 50 platters, each about 1/8-inch thick and 24 inches in diameter.[30] While the IBM 350 used only two read/write heads,[28] the 1301 used an array of heads, one per platter, moving as a single unit. Cylinder-mode read/write operations were supported, and the heads flew about 250 micro-inches (about 6 µm) above the platter surface. Motion of the head array depended upon a binary adder system of hydraulic actuators which assured repeatable positioning. The 1301 cabinet was about the size of three home refrigerators placed side by side, storing the equivalent of about 21 million eight-bit bytes. Access time was about a quarter of a second.

Also, in 1962, IBM introduced the model 1311 disk drive, which was about the size of a washing machine and stored two million characters on a removable disk pack. Users could buy additional packs and interchange them as needed, much like reels of magnetic tape. Later models of removable pack drives, from IBM and others, became the norm in most computer installations and reached capacities of 300 megabytes by the early 1980s. Non-removable HDDs were called "fixed disk" drives.

Some high-performance HDDs were manufactured with one head per track (e.g. IBM 2305 in 1970) so that no time was lost physically moving the heads to a track.[31] Known as fixed-head or head-per-track disk drives they were very expensive and are no longer in production.[32]

In 1973, IBM introduced a new type of HDD code-named "Winchester". Its primary distinguishing feature was that the disk heads were not withdrawn completely from the stack of disk platters when the drive was powered down. Instead, the heads were allowed to "land" on a special area of the disk surface upon spin-down, "taking off" again when the disk was later powered on. This greatly reduced the cost of the head actuator mechanism, but precluded removing just the disks from the drive as was done with the disk packs of the day. Instead, the first models of "Winchester technology" drives featured a removable disk module, which included both the disk pack and the head assembly, leaving the actuator motor in the drive upon removal. Later "Winchester" drives abandoned the removable media concept and returned to non-removable platters.

Like the first removable pack drive, the first "Winchester" drives used platters 14 inches (360 mm) in diameter. A few years later, designers were exploring the possibility that physically smaller platters might offer advantages. Drives with non-removable eight-inch platters appeared, and then drives that used a 5 1⁄4 in (130 mm) form factor (a mounting width equivalent to that used by contemporary floppy disk drives). The latter were primarily intended for the then-fledgling personal computer (PC) market.

As the 1980s began, HDDs were a rare and very expensive additional feature in PCs, but by the late 1980s their cost had been reduced to the point where they were standard on all but the cheapest computers.

Most HDDs in the early 1980s were sold to PC end users as an external, add-on subsystem. The subsystem was not sold under the drive manufacturer's name but under the subsystem manufacturer's name such as Corvus Systems and Tallgrass Technologies, or under the PC system manufacturer's name such as the Apple ProFile. The IBM PC/XT in 1983 included an internal 10 MB HDD, and soon thereafter internal HDDs proliferated on personal computers.

External HDDs remained popular for much longer on the Apple Macintosh. Many Macintosh computers made between 1986 and 1998 featured a SCSI port on the back, making external expansion simple. Older compact Macintosh computers did not have user-accessible hard drive bays (indeed, the Macintosh 128K, Macintosh 512K, and Macintosh Plus did not feature a hard drive bay at all), so on those models external SCSI disks were the only reasonable option for expanding upon any internal storage.

The 2011 Thailand floods damaged the manufacturing plants and impacted hard disk drive cost adversely between 2011 and 2013.[33]

Driven by ever increasing areal density, HDDs have continuously improved; a few highlights are listed in the table above. Market applications expanded through the 2000s, from the mainframe computers of the late 1950s to most mass storage applications including computers and consumer applications such as storage of entertainment content.

NAND performance is improving faster than HDDs, and applications for HDDs are eroding. Smaller form factors, 1.8-inches and below, were discontinued around 2010. The price of solid-state storage (NAND), represented by Moore's law, is improving faster than HDDs. NAND has a higher price elasticity of demand than HDDs, and this drives market growth.[34] During the late 2000s and 2010s, the product life cycle of HDDs entered a mature phase, and slowing sales may indicate the onset of the declining phase.[35]

Technology

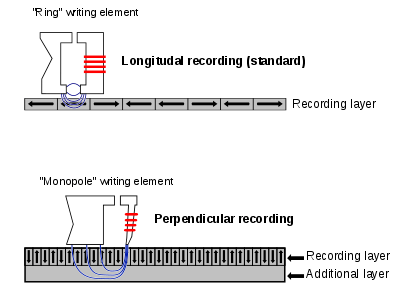

Magnetic recording

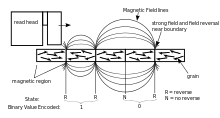

A modern HDD records data by magnetizing a thin film of ferromagnetic material[lower-alpha 5] on a disk. Sequential changes in the direction of magnetization represent binary data bits. The data is read from the disk by detecting the transitions in magnetization. User data is encoded using an encoding scheme, such as run-length limited encoding,[lower-alpha 6] which determines how the data is represented by the magnetic transitions.

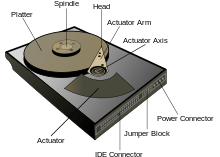

A typical HDD design consists of a spindle that holds flat circular disks, also called platters, which hold the recorded data. The platters are made from a non-magnetic material, usually aluminum alloy, glass, or ceramic. They are coated with a shallow layer of magnetic material typically 10–20 nm in depth, with an outer layer of carbon for protection.[37][38][39] For reference, a standard piece of copy paper is 0.07–0.18 mm (70,000–180,000 nm)[40] thick.

The platters in contemporary HDDs are spun at speeds varying from 4,200 rpm in energy-efficient portable devices, to 15,000 rpm for high-performance servers.[42] The first HDDs spun at 1,200 rpm[6] and, for many years, 3,600 rpm was the norm.[43] As of December 2013, the platters in most consumer-grade HDDs spin at either 5,400 rpm or 7,200 rpm.[44]

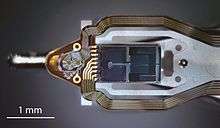

Information is written to and read from a platter as it rotates past devices called read-and-write heads that are positioned to operate very close to the magnetic surface, with their flying height often in the range of tens of nanometers. The read-and-write head is used to detect and modify the magnetization of the material passing immediately under it.

In modern drives, there is one head for each magnetic platter surface on the spindle, mounted on a common arm. An actuator arm (or access arm) moves the heads on an arc (roughly radially) across the platters as they spin, allowing each head to access almost the entire surface of the platter as it spins. The arm is moved using a voice coil actuator or in some older designs a stepper motor. Early hard disk drives wrote data at some constant bits per second, resulting in all tracks having the same amount of data per track but modern drives (since the 1990s) use zone bit recording – increasing the write speed from inner to outer zone and thereby storing more data per track in the outer zones.

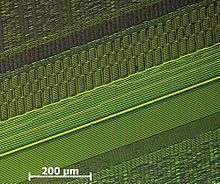

In modern drives, the small size of the magnetic regions creates the danger that their magnetic state might be lost because of thermal effects, thermally induced magnetic instability which is commonly known as the "superparamagnetic limit". To counter this, the platters are coated with two parallel magnetic layers, separated by a three-atom layer of the non-magnetic element ruthenium, and the two layers are magnetized in opposite orientation, thus reinforcing each other.[45] Another technology used to overcome thermal effects to allow greater recording densities is perpendicular recording, first shipped in 2005,[46] and as of 2007 the technology was used in many HDDs.[47][48][49]

In 2004, a new concept was introduced to allow further increase of the data density in magnetic recording, using recording media consisting of coupled soft and hard magnetic layers. That so-called exchange spring media, also known as exchange coupled composite media, allows good writability due to the write-assist nature of the soft layer. However, the thermal stability is determined only by the hardest layer and not influenced by the soft layer.[50][51]

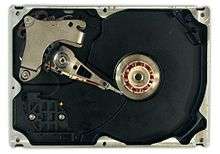

Components

A typical HDD has two electric motors; a spindle motor that spins the disks and an actuator (motor) that positions the read/write head assembly across the spinning disks. The disk motor has an external rotor attached to the disks; the stator windings are fixed in place. Opposite the actuator at the end of the head support arm is the read-write head; thin printed-circuit cables connect the read-write heads to amplifier electronics mounted at the pivot of the actuator. The head support arm is very light, but also stiff; in modern drives, acceleration at the head reaches 550 g.

The actuator is a permanent magnet and moving coil motor that swings the heads to the desired position. A metal plate supports a squat neodymium-iron-boron (NIB) high-flux magnet. Beneath this plate is the moving coil, often referred to as the voice coil by analogy to the coil in loudspeakers, which is attached to the actuator hub, and beneath that is a second NIB magnet, mounted on the bottom plate of the motor (some drives have only one magnet).

The voice coil itself is shaped rather like an arrowhead, and made of doubly coated copper magnet wire. The inner layer is insulation, and the outer is thermoplastic, which bonds the coil together after it is wound on a form, making it self-supporting. The portions of the coil along the two sides of the arrowhead (which point to the actuator bearing center) then interact with the magnetic field of the fixed magnet. Current flowing radially outward along one side of the arrowhead and radially inward on the other produces the tangential force. If the magnetic field were uniform, each side would generate opposing forces that would cancel each other out. Therefore, the surface of the magnet is half north pole and half south pole, with the radial dividing line in the middle, causing the two sides of the coil to see opposite magnetic fields and produce forces that add instead of canceling. Currents along the top and bottom of the coil produce radial forces that do not rotate the head.

The HDD's electronics control the movement of the actuator and the rotation of the disk, and perform reads and writes on demand from the disk controller. Feedback of the drive electronics is accomplished by means of special segments of the disk dedicated to servo feedback. These are either complete concentric circles (in the case of dedicated servo technology), or segments interspersed with real data (in the case of embedded servo technology). The servo feedback optimizes the signal to noise ratio of the GMR sensors by adjusting the voice-coil of the actuated arm. The spinning of the disk also uses a servo motor. Modern disk firmware is capable of scheduling reads and writes efficiently on the platter surfaces and remapping sectors of the media which have failed.

Error rates and handling

Modern drives make extensive use of error correction codes (ECCs), particularly Reed–Solomon error correction. These techniques store extra bits, determined by mathematical formulas, for each block of data; the extra bits allow many errors to be corrected invisibly. The extra bits themselves take up space on the HDD, but allow higher recording densities to be employed without causing uncorrectable errors, resulting in much larger storage capacity.[52] For example, a typical 1 TB hard disk with 512-byte sectors provides additional capacity of about 93 GB for the ECC data.[53]

In the newest drives, as of 2009,[54] low-density parity-check codes (LDPC) were supplanting Reed–Solomon; LDPC codes enable performance close to the Shannon Limit and thus provide the highest storage density available.[54][55]

Typical hard disk drives attempt to "remap" the data in a physical sector that is failing to a spare physical sector provided by the drive's "spare sector pool" (also called "reserve pool"),[56] while relying on the ECC to recover stored data while the number of errors in a bad sector is still low enough. The S.M.A.R.T (Self-Monitoring, Analysis and Reporting Technology) feature counts the total number of errors in the entire HDD fixed by ECC (although not on all hard drives as the related S.M.A.R.T attributes "Hardware ECC Recovered" and "Soft ECC Correction" are not consistently supported), and the total number of performed sector remappings, as the occurrence of many such errors may predict an HDD failure.

The "No-ID Format", developed by IBM in the mid-1990s, contains information about which sectors are bad and where remapped sectors have been located.[57]

Only a tiny fraction of the detected errors end up as not correctable. Examples of specified uncorrected bit read error rates include:

- 2013 specifications for enterprise SAS disk drives state the error rate to be one uncorrected bit read error in every 1016 bits read,[58][59]

- 2018 specifications for consumer SATA hard drives state the error rate to be one uncorrected bit read error in every 1014 bits.[60][61].

Within a given manufacturers model the uncorrected bit error rate is typically the same regardless of capacity of the drive.[58][59][60][61]

The worst type of errors are silent data corruptions which are errors undetected by the disk firmware or the host operating system; some of these errors may be caused by hard disk drive malfunctions while others originate elsewhere in the connection between the drive and the host.[62]

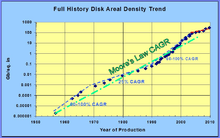

Development

The rate of areal density advancement was similar to Moore's law (doubling every two years) through 2010: 60% per year during 1988–1996, 100% during 1996–2003 and 30% during 2003–2010.[63] Gordon Moore (1997) called the increase "flabbergasting,"[64] while observing later that growth cannot continue forever.[65] Price improvement decelerated to −12% per year during 2010–2017,[66] as the growth of areal density slowed. The rate of advancement for areal density slowed to 10% per year during 2010–2016,[67] and there was difficulty in migrating from perpendicular recording to newer technologies.[68]

As bit cell size decreases, more data can be put onto a single drive platter. In 2013, a production desktop 3 TB HDD (with four platters) would have had an areal density of about 500 Gbit/in2 which would have amounted to a bit cell comprising about 18 magnetic grains (11 by 1.6 grains).[69] Since the mid-2000s areal density progress has increasingly been challenged by a superparamagnetic trilemma involving grain size, grain magnetic strength and ability of the head to write.[70] In order to maintain acceptable signal to noise smaller grains are required; smaller grains may self-reverse (electrothermal instability) unless their magnetic strength is increased, but known write head materials are unable to generate a magnetic field sufficient to write the medium. Several new magnetic storage technologies are being developed to overcome or at least abate this trilemma and thereby maintain the competitiveness of HDDs with respect to products such as flash memory–based solid-state drives (SSDs).

In 2013, Seagate introduced one such technology, shingled magnetic recording (SMR).[71] Additionally, SMR comes with design complexities that may cause reduced write performance.[72][73] Other new recording technologies that, as of 2016, still remain under development include heat-assisted magnetic recording (HAMR),[74][75] microwave-assisted magnetic recording (MAMR),[76][77] two-dimensional magnetic recording (TDMR),[69][78] bit-patterned recording (BPR),[79] and "current perpendicular to plane" giant magnetoresistance (CPP/GMR) heads.[80][81][82]

The rate of areal density growth has dropped below the historical Moore's law rate of 40% per year, and the deceleration is expected to persist through at least 2020. Depending upon assumptions on feasibility and timing of these technologies, the median forecast by industry observers and analysts for 2020 and beyond for areal density growth is 20% per year with a range of 10–30%.[83][84][85][86] The achievable limit for the HAMR technology in combination with BPR and SMR may be 10 Tbit/in2,[87] which would be 20 times higher than the 500 Gbit/in2 represented by 2013 production desktop HDDs. As of 2015, HAMR HDDs have been delayed several years, and are expected in 2018. They require a different architecture, with redesigned media and read/write heads, new lasers, and new near-field optical transducers.[88]

Capacity

The capacity of a hard disk drive, as reported by an operating system to the end user, is smaller than the amount stated by the manufacturer for several reasons: the operating system using some space, use of some space for data redundancy, and space use for file system structures. Also the difference in capacity reported in SI decimal prefixed units vs. binary prefixes can lead to a false impression of missing capacity.

Calculation

Modern hard disk drives appear to their host controller as a contiguous set of logical blocks, and the gross drive capacity is calculated by multiplying the number of blocks by the block size. This information is available from the manufacturer's product specification, and from the drive itself through use of operating system functions that invoke low-level drive commands.[89][90]

The gross capacity of older HDDs is calculated as the product of the number of cylinders per recording zone, the number of bytes per sector (most commonly 512), and the count of zones of the drive. Some modern SATA drives also report cylinder-head-sector (CHS) capacities, but these are not physical parameters because the reported values are constrained by historic operating system interfaces. The C/H/S scheme has been replaced by logical block addressing (LBA), a simple linear addressing scheme that locates blocks by an integer index, which starts at LBA 0 for the first block and increments thereafter.[91] When using the C/H/S method to describe modern large drives, the number of heads is often set to 64, although a typical hard disk drive, as of 2013, has between one and four platters.

In modern HDDs, spare capacity for defect management is not included in the published capacity; however, in many early HDDs a certain number of sectors were reserved as spares, thereby reducing the capacity available to the operating system.

For RAID subsystems, data integrity and fault-tolerance requirements also reduce the realized capacity. For example, a RAID 1 array has about half the total capacity as a result of data mirroring, while a RAID 5 array with x drives loses 1/x of capacity (which equals to the capacity of a single drive) due to storing parity information. RAID subsystems are multiple drives that appear to be one drive or more drives to the user, but provide fault tolerance. Most RAID vendors use checksums to improve data integrity at the block level. Some vendors design systems using HDDs with sectors of 520 bytes to contain 512 bytes of user data and eight checksum bytes, or by using separate 512-byte sectors for the checksum data.[92]

Some systems may use hidden partitions for system recovery, reducing the capacity available to the end user.

Formatting

Data is stored on a hard drive in a series of logical blocks. Each block is delimited by markers identifying its start and end, error detecting and correcting information, and space between blocks to allow for minor timing variations. These blocks often contained 512 bytes of usable data, but other sizes have been used. As drive density increased, an initiative known as Advanced Format extended the block size to 4096 bytes of usable data, with a resulting significant reduction in the amount of disk space used for block headers, error checking data, and spacing.

The process of initializing these logical blocks on the physical disk platters is called low-level formatting, which is usually performed at the factory and is not normally changed in the field.[93] High-level formatting writes data structures used by the operating system to organize data files on the disk. This includes writing partition and file system structures into selected logical blocks. For example, some of the disk space will be used to hold a directory of disk file names and a list of logical blocks associated with a particular file.

Examples of partition mapping scheme include Master boot record (MBR) and GUID Partition Table (GPT). Examples of data structures stored on disk to retrieve files include the File Allocation Table (FAT) in the DOS file system and inodes in many UNIX file systems, as well as other operating system data structures (also known as metadata). As a consequence, not all the space on an HDD is available for user files, but this system overhead is usually small compared with user data.

Units

| Capacity advertised by manufacturers[lower-alpha 7] | Capacity expected by some consumers[lower-alpha 8] | Reported capacity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Windows[lower-alpha 8] | macOS ver 10.6+[lower-alpha 7] | ||||

| With prefix | Bytes | Bytes | Diff. | ||

| 100 GB | 100,000,000,000 | 107,374,182,400 | 7.37% | 93.1 GB | 100 GB |

| 1 TB | 1,000,000,000,000 | 1,099,511,627,776 | 9.95% | 931 GB | 1,000 GB, 1,000,000 MB |

The total capacity of HDDs is given by manufacturers using SI decimal prefixes such as gigabytes (1 GB = 1,000,000,000 bytes) and terabytes (1 TB = 1,000,000,000,000 bytes).[94] This practice dates back to the early days of computing;[96] by the 1970s, "million", "mega" and "M" were consistently used in the decimal sense for drive capacity.[97][98][99] However, capacities of memory are quoted using a binary interpretation of the prefixes, i.e. using powers of 1024 instead of 1000.

Software reports hard disk drive or memory capacity in different forms using either decimal or binary prefixes. The Microsoft Windows family of operating systems uses the binary convention when reporting storage capacity, so an HDD offered by its manufacturer as a 1 TB drive is reported by these operating systems as a 931 GB HDD. Mac OS X 10.6 ("Snow Leopard") uses decimal convention when reporting HDD capacity.[100] The default behavior of the df command-line utility on Linux is to report the HDD capacity as a number of 1024-byte units.[101]

The difference between the decimal and binary prefix interpretation caused some consumer confusion and led to class action suits against HDD manufacturers. The plaintiffs argued that the use of decimal prefixes effectively misled consumers while the defendants denied any wrongdoing or liability, asserting that their marketing and advertising complied in all respects with the law and that no class member sustained any damages or injuries.[102][103][104]

Price evolution

HDD price per byte improved at the rate of −40% per year during 1988–1996, −51% per year during 1996–2003, and −34% per year during 2003–2010.[21][63] The price improvement decelerated to −13% per year during 2011–2014, as areal density increase slowed and the 2011 Thailand floods damaged manufacturing facilities.[68]

Form factors

IBM's first hard drive, the IBM 350, used a stack of fifty 24-inch platters and was of a size comparable to two large refrigerators. In 1962, IBM introduced its model 1311 disk, which used six 14-inch (nominal size) platters in a removable pack and was roughly the size of a washing machine. This became a standard platter size and drive form-factor for many years, used also by other manufacturers.[105] The IBM 2314 used platters of the same size in an eleven-high pack and introduced the "drive in a drawer" layout, although the "drawer" was not the complete drive.

Later drives were designed to fit entirely into a chassis that would mount in a 19-inch rack. Digital's RK05 and RL01 were early examples using single 14-inch platters in removable packs, the entire drive fitting in a 10.5-inch-high rack space (six rack units). In the mid-to-late 1980s the similarly sized Fujitsu Eagle, which used (coincidentally) 10.5-inch platters, was a popular product.

Such large platters were never used with microprocessor-based systems. With increasing sales of microcomputers having built in floppy-disk drives (FDDs), HDDs that would fit to the FDD mountings became desirable. Thus HDD Form factors, initially followed those of 8-inch, 5.25-inch, and 3.5-inch floppy disk drives. Although referred to by these nominal sizes, the actual sizes for those three drives respectively are 9.5″, 5.75″ and 4″ wide. Because there were no smaller floppy disk drives, smaller HDD form factors developed from product offerings or industry standards. 2.5-inch drives are actually 2.75″ wide.

As of 2012, 2.5-inch and 3.5-inch hard disks were the most popular sizes. By 2009, all manufacturers had discontinued the development of new products for the 1.3-inch, 1-inch and 0.85-inch form factors due to falling prices of flash memory,[106][107] which has no moving parts. While nominal sizes are in inches, actual dimensions are specified in millimeters.

Performance characteristics

The factors that limit the time to access the data on an HDD are mostly related to the mechanical nature of the rotating disks and moving heads.

Seek time is a measure of how long it takes the head assembly to travel to the track of the disk that contains data. The first HDD had an average seek time of about 600 ms.[6] Some early PC drives used a stepper motor to move the heads, and as a result had seek times as slow as 80–120 ms, but this was quickly improved by voice coil type actuation in the 1980s, reducing seek times to around 20 ms. Seek time has continued to improve slowly over time. The fastest server drives today have a seek time around 4 ms.[108] The average seek time is strictly the time to do all possible seeks divided by the number of all possible seeks, but in practice is determined by statistical methods or simply approximated as the time of a seek over one-third of the number of tracks.[109]

Rotational latency is incurred because the desired disk sector may not be directly under the head when data transfer is requested. Average rotational latency is shown in the table, based on the statistical relation that the average latency is one-half the rotational period.

The bit rate or data transfer rate (once the head is in the right position) creates delay which is a function of the number of blocks transferred; typically relatively small, but can be quite long with the transfer of large contiguous files.

Delay may also occur if the drive disks are stopped to save energy.

Defragmentation is a procedure used to minimize delay in retrieving data by moving related items to physically proximate areas on the disk.[110] Some computer operating systems perform defragmentation automatically. Although automatic defragmentation is intended to reduce access delays, performance will be temporarily reduced while the procedure is in progress.[111]

Time to access data can be improved by increasing rotational speed (thus reducing latency) or by reducing the time spent seeking. Increasing areal density increases throughput by increasing data rate and by increasing the amount of data under a set of heads, thereby potentially reducing seek activity for a given amount of data. The time to access data has not kept up with throughput increases, which themselves have not kept up with growth in bit density and storage capacity.

Latency

| Rotational speed [rpm] |

Average rotational latency [ms] |

|---|---|

| 15,000 | 2 |

| 10,000 | 3 |

| 7,200 | 4.16 |

| 5,400 | 5.55 |

| 4,800 | 6.25 |

Data transfer rate

As of 2010, a typical 7,200-rpm desktop HDD has a sustained "disk-to-buffer" data transfer rate up to 1,030 Mbit/s.[112] This rate depends on the track location; the rate is higher for data on the outer tracks (where there are more data sectors per rotation) and lower toward the inner tracks (where there are fewer data sectors per rotation); and is generally somewhat higher for 10,000-rpm drives. A current widely used standard for the "buffer-to-computer" interface is 3.0 Gbit/s SATA, which can send about 300 megabyte/s (10-bit encoding) from the buffer to the computer, and thus is still comfortably ahead of today's disk-to-buffer transfer rates. Data transfer rate (read/write) can be measured by writing a large file to disk using special file generator tools, then reading back the file. Transfer rate can be influenced by file system fragmentation and the layout of the files.[110]

HDD data transfer rate depends upon the rotational speed of the platters and the data recording density. Because heat and vibration limit rotational speed, advancing density becomes the main method to improve sequential transfer rates. Higher speeds require a more powerful spindle motor, which creates more heat. While areal density advances by increasing both the number of tracks across the disk and the number of sectors per track,[113] only the latter increases the data transfer rate for a given rpm. Since data transfer rate performance tracks only one of the two components of areal density, its performance improves at a lower rate.

Other considerations

Other performance considerations include quality-adjusted price, power consumption, audible noise, and both operating and non-operating shock resistance.

The Federal Reserve Board has a quality-adjusted price index for large-scale enterprise storage systems including three or more enterprise HDDs and associated controllers, racks and cables. Prices for these large-scale storage systems improved at the rate of ‒30% per year during 2004–2009 and ‒22% per year during 2009–2014.[63]

Access and interfaces

Current hard drives connect to a computer over one of several bus types, including parallel ATA, Serial ATA , SCSI, Serial Attached SCSI (SAS), and Fibre Channel. Some drives, especially external portable drives, use IEEE 1394, or USB. All of these interfaces are digital; electronics on the drive process the analog signals from the read/write heads. Current drives present a consistent interface to the rest of the computer, independent of the data encoding scheme used internally, and independent of the physical number of disks and heads within the drive.

Typically a DSP in the electronics inside the drive takes the raw analog voltages from the read head and uses PRML and Reed–Solomon error correction[114] to decode the data, then sends that data out the standard interface. That DSP also watches the error rate detected by error detection and correction, and performs bad sector remapping, data collection for Self-Monitoring, Analysis, and Reporting Technology, and other internal tasks.

Modern interfaces connect the drive to the host interface with a single data/control cable. Each drive also has an additional power cable, usually direct to the power supply unit. Older interfaces had separate cables for data signals and for drive control signals.

- Small Computer System Interface (SCSI), originally named SASI for Shugart Associates System Interface, was standard on servers, workstations, Commodore Amiga, Atari ST and Apple Macintosh computers through the mid-1990s, by which time most models had been transitioned to IDE (and later, SATA) family disks. The length limit of the data cable allows for external SCSI devices.

- Integrated Drive Electronics (IDE), later standardized under the name AT Attachment (ATA, with the alias PATA (Parallel ATA) retroactively added upon introduction of SATA) moved the HDD controller from the interface card to the disk drive. This helped to standardize the host/controller interface, reduce the programming complexity in the host device driver, and reduced system cost and complexity. The 40-pin IDE/ATA connection transfers 16 bits of data at a time on the data cable. The data cable was originally 40-conductor, but later higher speed requirements led to an "ultra DMA" (UDMA) mode using an 80-conductor cable with additional wires to reduce cross talk at high speed.

- EIDE was an unofficial update (by Western Digital) to the original IDE standard, with the key improvement being the use of direct memory access (DMA) to transfer data between the disk and the computer without the involvement of the CPU, an improvement later adopted by the official ATA standards. By directly transferring data between memory and disk, DMA eliminates the need for the CPU to copy byte per byte, therefore allowing it to process other tasks while the data transfer occurs.

- Fibre Channel (FC) is a successor to parallel SCSI interface on enterprise market. It is a serial protocol. In disk drives usually the Fibre Channel Arbitrated Loop (FC-AL) connection topology is used. FC has much broader usage than mere disk interfaces, and it is the cornerstone of storage area networks (SANs). Recently other protocols for this field, like iSCSI and ATA over Ethernet have been developed as well. Confusingly, drives usually use copper twisted-pair cables for Fibre Channel, not fibre optics. The latter are traditionally reserved for larger devices, such as servers or disk array controllers.

- Serial Attached SCSI (SAS). The SAS is a new generation serial communication protocol for devices designed to allow for much higher speed data transfers and is compatible with SATA. SAS uses a mechanically identical data and power connector to standard 3.5-inch SATA1/SATA2 HDDs, and many server-oriented SAS RAID controllers are also capable of addressing SATA HDDs. SAS uses serial communication instead of the parallel method found in traditional SCSI devices but still uses SCSI commands.

- Serial ATA (SATA). The SATA data cable has one data pair for differential transmission of data to the device, and one pair for differential receiving from the device, just like EIA-422. That requires that data be transmitted serially. A similar differential signaling system is used in RS485, LocalTalk, USB, FireWire, and differential SCSI.

Integrity and failure

Due to the extremely close spacing between the heads and the disk surface, HDDs are vulnerable to being damaged by a head crash – a failure of the disk in which the head scrapes across the platter surface, often grinding away the thin magnetic film and causing data loss. Head crashes can be caused by electronic failure, a sudden power failure, physical shock, contamination of the drive's internal enclosure, wear and tear, corrosion, or poorly manufactured platters and heads.

The HDD's spindle system relies on air density inside the disk enclosure to support the heads at their proper flying height while the disk rotates. HDDs require a certain range of air densities to operate properly. The connection to the external environment and density occurs through a small hole in the enclosure (about 0.5 mm in breadth), usually with a filter on the inside (the breather filter).[115] If the air density is too low, then there is not enough lift for the flying head, so the head gets too close to the disk, and there is a risk of head crashes and data loss. Specially manufactured sealed and pressurized disks are needed for reliable high-altitude operation, above about 3,000 m (9,800 ft).[116] Modern disks include temperature sensors and adjust their operation to the operating environment. Breather holes can be seen on all disk drives – they usually have a sticker next to them, warning the user not to cover the holes. The air inside the operating drive is constantly moving too, being swept in motion by friction with the spinning platters. This air passes through an internal recirculation (or "recirc") filter to remove any leftover contaminants from manufacture, any particles or chemicals that may have somehow entered the enclosure, and any particles or outgassing generated internally in normal operation. Very high humidity present for extended periods of time can corrode the heads and platters.

For giant magnetoresistive (GMR) heads in particular, a minor head crash from contamination (that does not remove the magnetic surface of the disk) still results in the head temporarily overheating, due to friction with the disk surface, and can render the data unreadable for a short period until the head temperature stabilizes (so called "thermal asperity", a problem which can partially be dealt with by proper electronic filtering of the read signal).

When the logic board of a hard disk fails, the drive can often be restored to functioning order and the data recovered by replacing the circuit board with one of an identical hard disk. In the case of read-write head faults, they can be replaced using specialized tools in a dust-free environment. If the disk platters are undamaged, they can be transferred into an identical enclosure and the data can be copied or cloned onto a new drive. In the event of disk-platter failures, disassembly and imaging of the disk platters may be required.[117] For logical damage to file systems, a variety of tools, including fsck on UNIX-like systems and CHKDSK on Windows, can be used for data recovery. Recovery from logical damage can require file carving.

A common expectation is that hard disk drives designed and marketed for server use will fail less frequently than consumer-grade drives usually used in desktop computers. However, two independent studies by Carnegie Mellon University[118] and Google[119] found that the "grade" of a drive does not relate to the drive's failure rate.

A 2011 summary of research, into SSD and magnetic disk failure patterns by Tom's Hardware summarized research findings as follows:[120]

- Mean time between failures (MTBF) does not indicate reliability; the annualized failure rate is higher and usually more relevant.

- Magnetic disks do not have a specific tendency to fail during early use, and temperature has only a minor effect; instead, failure rates steadily increase with age.

- S.M.A.R.T. warns of mechanical issues but not other issues affecting reliability, and is therefore not a reliable indicator of condition.[121]

- Failure rates of drives sold as "enterprise" and "consumer" are "very much similar", although these drive types are customized for their different operating environments.[122][123]

- In drive arrays, one drive's failure significantly increases the short-term risk of a second drive failing.

Market segments

- Desktop HDDs

- They typically store between 60 GB and 4 TB and rotate at 5,400 to 10,000 rpm, and have a media transfer rate of 0.5 Gbit/s or higher (1 GB = 109 bytes; 1 Gbit/s = 109 bit/s). As of February 2017, the highest-capacity desktop HDDs stored 12 TB,[14] with plans to release a 14TB one in later 2017.[124] As of 2016, the typical speed of a hard drive in an average desktop computer is 7200 RPM, whereas low-cost desktop computers may use 5900 RPM or 5400 RPM drives. For some time in the 2000s and early 2010s some desktop users would also use 10k RPM drives such as Western Digital Raptor but such drives have become much rarer as of 2016 and are not commonly used now, having been replaced by NAND flash-based SSDs.

- Mobile (laptop) HDDs

Two enterprise-grade SATA 2.5-inch 10,000 rpm HDDs, factory-mounted in 3.5-inch adapter frames

Two enterprise-grade SATA 2.5-inch 10,000 rpm HDDs, factory-mounted in 3.5-inch adapter frames- Smaller than their desktop and enterprise counterparts, they tend to be slower and have lower capacity. Mobile HDDs spin at 4,200 rpm, 5,200 rpm, 5,400 rpm, or 7,200 rpm, with 5,400 rpm being typical. 7,200 rpm drives tend to be more expensive and have smaller capacities, while 4,200 rpm models usually have very high storage capacities. Because of smaller platter(s), mobile HDDs generally have lower capacity than their desktop counterparts.

- There are also 2.5-inch drives spinning at 10,000 rpm, which belong to the enterprise segment with no intention to be used in laptops.

- Enterprise HDDs

- Typically used with multiple-user computers running enterprise software. Examples are: transaction processing databases, internet infrastructure (email, webserver, e-commerce), scientific computing software, and nearline storage management software. Enterprise drives commonly operate continuously ("24/7") in demanding environments while delivering the highest possible performance without sacrificing reliability. Maximum capacity is not the primary goal, and as a result the drives are often offered in capacities that are relatively low in relation to their cost.[125]

- The fastest enterprise HDDs spin at 10,000 or 15,000 rpm, and can achieve sequential media transfer speeds above 1.6 Gbit/s[126] and a sustained transfer rate up to 1 Gbit/s.[126] Drives running at 10,000 or 15,000 rpm use smaller platters to mitigate increased power requirements (as they have less air drag) and therefore generally have lower capacity than the highest capacity desktop drives. Enterprise HDDs are commonly connected through Serial Attached SCSI (SAS) or Fibre Channel (FC). Some support multiple ports, so they can be connected to a redundant host bus adapter.

- Enterprise HDDs can have sector sizes larger than 512 bytes (often 520, 524, 528 or 536 bytes). The additional per-sector space can be used by hardware RAID controllers or applications for storing Data Integrity Field (DIF) or Data Integrity Extensions (DIX) data, resulting in higher reliability and prevention of silent data corruption.[127]

- Consumer electronics HDDs

- They include drives embedded into digital video recorders and automotive vehicles. The former are configured to provide a guaranteed streaming capacity, even in the face of read and write errors, while the latter are built to resist larger amounts of shock. They usually spin at a speed of 5400 RPM.

Manufacturers and sales

More than 200 companies have manufactured HDDs over time. But consolidations have concentrated production into just three manufacturers today: Western Digital, Seagate, and Toshiba.

Worldwide revenue for disk storage declined 4% per year, from a peak of $38 billion in 2012 to $27 billion in 2016. Production of HDDs grew 16% per year, from 335 exabytes in 2011 to 693 exabytes in 2016. Shipments declined 7% per year during this time period, from 620 million units to 425 million.[67] Seagate and Western Digital each have 40–45% of unit shipments, while Toshiba has 13–17%. The average sales price for the two largest manufacturers was $60 per unit in 2015.[128]

Competition from solid-state drives

The maximum areal storage density for flash memory used in solid state drives (SSDs) is 2.8 Tbit/in2 in laboratory demonstrations as of 2016, and the maximum for HDDs is 1.5 Tbit/in2. The areal density of flash memory is doubling every two years, similar to Moore's law (40% per year) and faster than the 10–20% per year for HDDs. As of 2016, maximum capacity was 10 terabytes for an HDD,[129] and 15 terabytes for an SSD.[24] HDDs were used in 70% of the desktop and notebook computers produced in 2016, and SSDs were used in 30%. The usage share of HDDs is declining and could drop below 50% in 2018–2019 according to one forecast, because SSDs are replacing smaller-capacity (less than one-terabyte) HDDs in desktop and notebook computers and MP3 players.[130]

The market for silicon-based flash memory (NAND) chips, used in SSDs and other applications, is growing rapidly. Worldwide revenue grew 12% per year during 2011–2016. It rose from $22 billion in 2011 to $39 billion in 2016, while production grew 46% per year from 19 exabytes to 120 exabytes.[67]

External hard disk drives

External hard disk drives typically connect via USB; variants using USB 2.0 interface generally have slower data transfer rates when compared to internally mounted hard drives connected through SATA. Plug and play drive functionality offers system compatibility and features large storage options and portable design. As of March 2015, available capacities for external hard disk drives ranged from 500 GB to 10 TB.[131]

External hard disk drives are usually available as pre-assembled integrated products, but may be also assembled by combining an external enclosure (with USB or other interface) with a separately purchased drive. They are available in 2.5-inch and 3.5-inch sizes; 2.5-inch variants are typically called portable external drives, while 3.5-inch variants are referred to as desktop external drives. "Portable" drives are packaged in smaller and lighter enclosures than the "desktop" drives; additionally, "portable" drives use power provided by the USB connection, while "desktop" drives require external power bricks.

Features such as biometric security or multiple interfaces (for example, Firewire) are available at a higher cost.[132] There are pre-assembled external hard disk drives that, when taken out from their enclosures, cannot be used internally in a laptop or desktop computer due to embedded USB interface on their printed circuit boards, and lack of SATA (or Parallel ATA) interfaces.[133][134]

In GUIs, hard disk drives are commonly symbolized with a drive icon

In GUIs, hard disk drives are commonly symbolized with a drive icon

See also

Notes

- ↑ This is the original filing date of the application which led to US Patent 3,503,060, generally accepted as the definitive disk drive patent.[1]

- ↑ Further inequivalent terms used to describe various hard disk drives include disk drive, disk file, direct access storage device (DASD), CKD disk, and Winchester disk drive (after the IBM 3340). The term "DASD" includes other devices beside disks.

- ↑ Comparable in size to a large side-by-side refrigerator.

- ↑ The 1.8-inch form factor is obsolete; sizes smaller than 2.5 inches have been replaced by flash memory.

- ↑ Initially gamma iron oxide particles in an epoxy binder, the recording layer in a modern HDD typically is domains of a granular Cobalt-Chrome-Platinum-based alloy physically isolated by an oxide to enable perpendicular recording.[36]

- ↑ Historically a variety of run-length limited codes have been used in magnetic recording including for example, codes named FM, MFM and GCR which are no longer used in modern HDDs.

- 1 2 Expressed using decimal multiples.

- 1 2 Expressed using binary multiples.

References

- ↑ Kean, David W., "IBM San Jose, A quarter century of innovation", 1977.

- ↑ Arpaci-Dusseau, Remzi H.; Arpaci-Dusseau, Andrea C. (2014). "Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces, Chapter: Hard Disk Drives" (PDF). Arpaci-Dusseau Books.

- ↑ Patterson, David; Hennessy, John (1971). Computer Organization and Design: The Hardware/Software Interface. Elsevier. p. 23.

- ↑ Domingo, Joel. "SSD vs. HDD: What's the Difference?". PC Magazine UK. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ↑ "Implications of non-volatile memory as primary storage for database management systems". IEEE. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "IBM Archives: IBM 350 disk storage unit". Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Validating the Reliability of Intel Solid-State Drives" (PDF). Intel. July 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

- ↑ Fullerton, Eric (March 2018). "5th Non-Volatile Memories Workshop (NVMW 2018)" (PDF). IEEE. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ Handy, James (July 31, 2012). "For the Lack of a Fab..." Objective Analysis. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- 1 2 Hutchinson, Lee. (June 25, 2012) How SSDs conquered mobile devices and modern OSes. Ars Technica. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- 1 2 Santo Domingo, Joel (May 10, 2012). "SSD vs HDD: What's the Difference?". PC Magazine. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- ↑ Hough, Jack (May 14, 2018). "Why Western Digital Can Gain 45% Despite Declining HDD Business". Barron’s. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- 1 2 "Time Capsule, 1956 Hard Disk". Oracle Magazine. Oracle. July 2014. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

IBM 350 disk drive held 3.75 MB

- 1 2 "Ultrastar Hs14". HGST. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ↑ 14,000,000,000,000 divided by 3,750,000.

- 1 2 "Toshiba Storage Solutions – MK3233GSG".

- ↑ 68 x 12 x 12 x 12 divided by 2.1 .

- ↑ 910,000 divided by 62.

- ↑ 600 divided by 2.5 .

- ↑ Ballistic Research Laboratories "A THIRD SURVEY OF DOMESTIC ELECTRONIC DIGITAL COMPUTING SYSTEMS," March 1961, section on IBM 305 RAMAC (p. 314-331) states a $34,500 purchase price which calculates to $9,200/MB.

- 1 2 John C. McCallum (May 16, 2015). "Disk Drive Prices (1955–2015)". jcmit.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2015. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

- ↑ 9,200,000 divided by 0.032 .

- ↑ "Magnetic head development". IBM Archives. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- 1 2 Coughlin, Tom (February 3, 2016). "Flash Memory Areal Densities Exceed Those of Hard Drives". forbes.com. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- ↑ 1,300,000,000,000 divided by 2,000.

- ↑ https://www.hgst.com/products/hard-drives/ultrastar-he12

- ↑ 2,500,000 divided by 2,000.

- 1 2 "IBM Archives: IBM 350 disk storage unit". IBM. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- ↑ "IBM Archives: IBM 1301 disk storage unit". ibm.com.

- ↑ "DiskPlatter-1301". computermuseum.li. Archived from the original on March 28, 2015.

- ↑ Microsoft Windows NT Workstation 4.0 Resource Guide 1995, Chapter 17 – Disk and File System Basics

- ↑ P. PAL Chaudhuri, P. Pal (April 15, 2008). Computer Organization and Design (3rd Edition). PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. p. 568. ISBN 978-81-203-3511-0.

- ↑ "Farming hard drives: how Backblaze weathered the Thailand drive crisis". blaze.com. 2013. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ↑ Kanellos, Michael (January 17, 2006). "Flash goes the notebook". CNET. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ↑ "Industry Life Cycle - Encyclopedia - Business Terms | Inc.com". Inc Magazine. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ↑ New Paradigms in Magnetic Recording

- ↑ "Hard Drives". escotal.com. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ↑ "What is a "head-crash" & how can it result in permanent loss of my hard drive data?". data-master.com. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ↑ "Hard Drive Help". hardrivehelp.com. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ↑ Elert, Glenn. "Thickness of a Piece of Paper". hypertextbook.com. Retrieved July 9, 2011.

- ↑ CMOS-MagView is an instrument that visualizes magnetic field structures and strengths.

- ↑ Blount, Walker C. (November 2007). "Why 7,200 RPM Mobile Hard Disk Drives?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 19, 2012. Retrieved July 17, 2011.

- ↑ "Ref — Hard Disk Spindle Motor". PC Guide. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- ↑ "Choosing High Performance Storage is not about RPM any more". Seagate. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

- ↑ Hayes, Brian. "Terabyte Territory". American Scientist. p. 212.

- ↑ "Press Releases December 14, 2004". Toshiba. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

- ↑ "Seagate Momentus 2½" HDDs per webpage January 2008". Seagate.com. October 24, 2008. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

- ↑ "Seagate Barracuda 3½" HDDs per webpage January 2008". Seagate.com. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

- ↑ "Western Digital Scorpio 2½" and Greenpower 3½" HDDs per quarterly conference, July 2007". Wdc.com. Archived from the original on March 16, 2009. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

- ↑ "Exchange spring recording media for areal densities up to 10Tbit/in2, J. Magn. Mag. Mat., D. Suess et al, 2004 online".

- ↑ "Composite media for perpendicular magnetic recording, IEEE Trans. Mag. Mat., R. Victora et al, 2005".

- ↑ Error Correcting Code, The PC Guide

- ↑ Curtis E. Stevens (2011). "Advanced Format in Legacy Infrastructures: More Transparent than Disruptive" (PDF). idema.org. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- 1 2 "Iterative Detection Read Channel Technology in Hard Disk Drives", Hitachi

- ↑ "2.5-inch Hard Disk Drive with High Recording Density and High Shock Resistance, Toshiba, 2011

- ↑ MjM Data Recovery Ltd. "MJM Data Recovery Ltd: Hard Disk Bad Sector Mapping Techniques". Datarecovery.mjm.co.uk. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ↑ Charles M. Kozierok. "The PC Guide: Hard Disk: Sector Format and Structure". 1997–2004.

- 1 2 "Enterprise Performance 15K HDD: Data Sheet" (PDF). Seagate. 2013. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- 1 2 "WD Xe: Datacenter hard drives" (PDF). Western Digital. 2013. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- 1 2 "3.5" BarraCuda data sheet" (PDF). Seagate. June 2018. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- 1 2 "WD Red Desktop/Mobile Series Spec Sheet" (PDF). Western Digital. April 2018. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- ↑ David S. H. Rosenthal (October 1, 2010). "Keeping Bits Safe: How Hard Can It Be?". ACM Queue. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Byrne, David (July 1, 2015). "Prices for Data Storage Equipment and the State of IT Innovation". The Federal Reserve Board FEDS Notes. p. Table 2. Retrieved July 5, 2015.

- ↑ "Gallium Arsenide". PC Magazine. March 25, 1997. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

Gordon Moore: ... the ability of the magnetic disk people to continue to increase the density is flabbergasting--that has moved at least as fast as the semiconductor complexity.

- ↑ Dubash, Manek (April 13, 2010). "Moore's Law is dead, says Gordon Moore". techworld.com. Archived from the original on July 6, 2014. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

It can't continue forever. The nature of exponentials is that you push them out and eventually disaster happens.

- ↑ John C. McCallum (2017). "Disk Drive Prices (1955–2017)". Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Gary M. Decad; Robert E. Fontana Jr. (July 6, 2017). "A Look at Cloud Storage Component Technologies Trends and Future Projections". ibmsystemsmag.com. p. Table 1. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- 1 2 Mellor, Chris (November 10, 2014). "Kryder's law craps out: Race to UBER-CHEAP STORAGE is OVER". theregister.co.uk. UK: The Register. Retrieved November 12, 2014.

The 2011 Thai floods almost doubled disk capacity cost/GB for a while. Rosenthal writes: 'The technical difficulties of migrating from PMR to HAMR, meant that already in 2010 the Kryder rate had slowed significantly and was not expected to return to its trend in the near future. The floods reinforced this.'

- 1 2 Dave Anderson (2013). "HDD Opportunities & Challenges, Now to 2020" (PDF). Seagate. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

'PMR CAGR slowing from historical 40+% down to ~8-12%' and 'HAMR CAGR = 20-40% for 2015–2020'

- ↑ Plumer et. al, Martin L. (March 2011). "New Paradigms in Magnetic Recording" (PDF). Physics in Canada. 67 (1): 25–29. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- ↑ "Seagate Delivers On Technology Milestone: First to Ship Hard Drives Using Next-Generation Shingled Magnetic Recording" (Press release). New York,: Seagate Technology plc. seagate.com. September 9, 2013. Archived from the original on October 9, 2014. Retrieved July 5, 2014.

Shingled Magnetic Technology is the First Step to Reaching a 20 Terabyte Hard Drive by 2020

- ↑ Jake Edge (March 26, 2014). "Support for shingled magnetic recording devices". LWN.net. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ↑ Jonathan Corbet (April 23, 2013). "LSFMM: A storage technology update". LWN.net. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

A 'shingled magnetic recording' (SMR) drive is a rotating drive that packs its tracks so closely that one track cannot be overwritten without destroying the neighboring tracks as well. The result is that overwriting data requires rewriting the entire set of closely-spaced tracks; that is an expensive tradeoff, but the benefit—much higher storage density—is deemed to be worth the cost in some situations.

- ↑ "Xyratex no-go for bit-patterned media". The Register. April 24, 2010. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ↑ "Report: TDK Technology "More Than Doubles" Capacity Of HDDs". Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ↑ Mallary et. al, Mike (July 2014). "Head and Media Challenges for 3 Tb/in2 Microwave-Assisted Magnetic Recording". IEEE TransMag. IEEE. 50 (7): 3001008.

- ↑ Li, Shaojing; Livshitz, Boris; Bertram, H. Neal; Schabes, Manfred; Schrefl, Thomas; Fullerton, Eric E.; Lomakin, Vitaliy (2009). "Microwave assisted magnetization reversal in composite media" (PDF). Applied Physics Letters. 94 (20): 202509. Bibcode:2009ApPhL..94t2509L. doi:10.1063/1.3133354.

- ↑ Wood, Roger (October 19, 2010). "Shingled Magnetic Recording and Two-Dimensional Magnetic Recording" (PDF). ewh.ieee.org. Hitachi GST. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Will Toshiba's Bit-Patterned Drives Change the HDD Landscape?". PC Magazine. August 19, 2010. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ↑ Coughlin, Thomas; Grochowski, Edward (June 19, 2012). "Years of Destiny: HDD Capital Spending and Technology Developments from 2012–2016" (PDF). IEEE Santa Clara Valley Magnetics Society. Retrieved October 9, 2012.

- ↑ All-Heusler giant-magnetoresistance junctions with matched energy bands and Fermi surfaces

- ↑ "Perpendicular Magnetic Recording Explained - Animation".

- ↑ Mark Re (August 25, 2015). "Tech Talk on HDD Areal Density" (PDF). Seagate. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

15–30% CAGR (est.) 2015 through early 2020s; HAMR, TDMR, BPM

- ↑ Raymond, Robert M. (September 9, 2013). "Current and Emerging Storage Technologies iCAS2013" (PDF). In Mahoney III, William P. Storage Technologies Areal Density Trends. International Computing for the Atmospheric Sciences Symposium (iCAS2013). Annecy, France: ORACLE Corp. at National Center for Atmospheric Research under sponsorship from the U.S. National Science Foundation.

page 11: Areal Density (Gbits/in^2) HDD Products 2010–2022 10-20%/year?

- ↑ Fontana, R.; Decad, G.; Hetzler, S. (September 20, 2012). "Technology Roadmap Comparisons for TAPE, HDD, and NAND Flash: Implications for Data Storage Applications" (PDF). digitalpreservation.gov. Washington D.C.: The Library of Congress. p. 18. Retrieved July 5, 2014.

Annual Areal Density Growth Rate Scenarios: HDD 20%/yr 2012–2017

- ↑ Kaur, Simran (September 15, 2014). "Seagate treads safely in uncertain demand environment; narrow moat has negative trend". Morningstar. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

a slowing areal density curve … that slowed around 2010 and will advance areal density 25% annually till 2020.

- ↑ Christoph Vogler; Claas Abert; Florian Bruckner; Dieter Suess; Dirk Praetorius (December 14, 2015). "Areal density optimizations for heat-assisted-magnetic recording of high density bit-patterned media". arXiv:1512.03690.

- ↑ Anton Shilov (December 18, 2015). "Hard Disk Drives with HAMR Technology Set to Arrive in 2018". Retrieved January 2, 2016.

Unfortunately, mass production of actual hard drives featuring HAMR has been delayed for a number of times already and now it turns out that the first HAMR-based HDDs are due in 2018. ... HAMR HDDs will feature a new architecture, require new media, completely redesigned read/write heads with a laser as well as a special near-field optical transducer (NFT) and a number of other components not used or mass produced today.

- ↑ Information technology – Serial Attached SCSI – 2 (SAS-2), INCITS 457 Draft 2, May 8, 2009, chapter 4.1 Direct-access block device type model overview,

The LBAs on a logical unit shall begin with zero and shall be contiguous up to the last logical block on the logical unit.

- ↑ ISO/IEC 791D:1994, AT Attachment Interface for Disk Drives (ATA-1), section 7.1.2

- ↑ "LBA Count for Disk Drives Standard (Document LBA1-03)" (PDF). IDEMA. June 15, 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ↑ "How to Measure Storage Efficiency – Part II – Taxes". Blogs.netapp.com. August 14, 2009. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ↑ "Low-Level Formatting". Archived from the original on June 4, 2017. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- 1 2 "Storage Solutions Guide" (PDF). Seagate. October 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 20, 2013. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ↑ "MKxx33GSG MK1235GSL r1" (PDF). Toshiba. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 22, 2009. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- ↑ "650 RAMAC announcement".

- ↑ Mulvany, R.B., "Engineering Design of a Disk Storage Facility with Data Modules". IBM JRD, November 1974

- ↑ Introduction to IBM Direct Access Storage Devices, M. Bohl, IBM publication SR20-4738. 1981.

- ↑ CDC Product Line Card, October 1974.

- ↑ Apple Support Team. "How OS X and iOS report storage capacity". Apple, Inc.

- ↑ "df(1) – Linux man page". linux.die.net. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- ↑ "Western Digital Settles Hard-Drive Capacity Lawsuit, Associated Press June 28, 2006". Fox News. March 22, 2001. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ↑ Published on October 26, 2007 by Phil Cogar (October 26, 2007). "Seagate lawsuit concludes, settlement announced". Bit-tech.net. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ↑ "Western Digital – Notice of Class Action Settlement email". Xtremesystems.org. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ↑ Emerson W. Pugh, Lyle R. Johnson, John H. Palmer IBM's 360 and early 370 systems MIT Press, 1991 ISBN 0-262-16123-0, page 266.

- ↑ Flash price fall shakes HDD market, EETimes Asia, August 1, 2007.

- ↑ In 2008 Samsung introduced the 1.3-inch SpinPoint A1 HDD but by March 2009 the family was listed as End Of Life Products and new 1.3-inch models were not available in this size.

- ↑ Anand Lal Shimpi (April 6, 2010). "Western Digital's New VelociRaptor VR200M: 10K RPM at 450GB and 600GB". anandtech.com. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- ↑ "Western Digital definition of Average Access Time". Wdc.com. July 1, 2006. Archived from the original on April 27, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- 1 2 Kearns, Dave (April 18, 2001). "How to defrag". ITWorld.

- ↑ Broida, Rick (April 10, 2009). "Turning Off Disk Defragmenter May Solve a Sluggish PC". PCWorld.

- ↑ "Speed Considerations". Seagate. Archived from the original on February 10, 2011. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ↑ "GLOSSARY of DRIVE and COMPUTER TERMS". Seagate. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- ↑ "Reed Solomon Codes – Introduction". Archived from the original on July 8, 2011.

- ↑ "Micro House PC Hardware Library Volume I: Hard Drives, Scott Mueler, Macmillan Computer Publishing". Alasir.com. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ↑ "Ruggedized Disk Drives for Commercial Airborne Computer Systems" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 4, 2012.

- ↑ Grabianowski, Ed. "How To Recover Lost Data from Your Hard Drive". HowStuffWorks. pp. 5–6. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ↑ "Everything You Know About Disks Is Wrong". Storagemojo.com. February 22, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- ↑ Eduardo Pinheiro; Wolf-Dietrich Weber; Luiz André Barroso (February 2007). "Failure Trends in a Large Disk Drive Population" (PDF). Google Inc. Retrieved December 26, 2011.

- ↑ Investigation: Is Your SSD More Reliable Than A Hard Drive? – Tom's Hardware long term SSD reliability review, 2011, "final words"

- ↑ Anthony, Sebastian. "Using SMART to accurately predict when a hard drive is about to die". ExtremeTech. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Consumer hard drives as reliable as enterprise hardware". Alphr. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ↑ Beach, Brian. "Enterprise Drives: Fact or Fiction?". Backblaze. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ↑ "Western Digital announces high-capacity 12TB, 14TB helium-filled hard drives".

- ↑ "Enterprise-class versus Desktop class Hard Drives" (PDF). Intel. Retrieved September 25, 2013.

- 1 2 Seagate Cheetah 15K.5 Data Sheet

- ↑ Martin K. Petersen (August 30, 2008). "Linux Data Integrity" (PDF). Oracle Corporation. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 9, 2015. Retrieved January 23, 2015.

Most disk drives use 512-byte sectors. [...] Enterprise drives (Parallel SCSI/SAS/FC) support 520/528 byte 'fat' sectors.

- ↑ Anton Shilov (March 2, 2016). "Hard Drive Shipments Drop by Nearly 17% in 2015". Retrieved July 5, 2016.

- ↑ Lucas Mearian (December 2, 2015). "WD ships world's first 10TB helium-filled hard drive". Computerworld. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- ↑ Coughlin, Tom (June 7, 2016). "3D NAND Enables Larger Consumer SSDs". forbes.com. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Seagate Backup Plus External Hard Drive Review (8TB)". storagereview.com. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Back Up Your Important Data to External Hard disk drive | Biometric Safe | Info and Products Reviews about Biometric Security Device –". Biometricsecurityproducts.org. July 26, 2011. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ↑ "Western Digital My Passport, 2 TB". hwigroup.net. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

Example of a pre-assembled external hard disk drive without its enclosure that cannot be used internally on a laptop or desktop due to the embedded interface on its printed circuit board

- ↑ Sebean Hsiung (May 5, 2010). "How to bypass USB controller and use as a SATA drive". datarecoverytools.co.uk. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

Further reading

External links

- Hard Disk Drives Encyclopedia

- Video showing an opened HD working

- Average seek time of a computer disk

- Timeline: 50 Years of Hard Drives

- HDD from inside: Tracks and Zones. How hard it can be?

- Hard disk hacking – firmware modifications, in eight parts, going as far as booting a Linux kernel on an ordinary HDD controller board

- Hiding Data in Hard Drive’s Service Areas, February 14, 2013, by Ariel Berkman

- Rotary Acceleration Feed Forward (RAFF) Information Sheet, Western Digital, January 2013

- PowerChoice Technology for Hard Disk Drive Power Savings and Flexibility, Seagate Technology, March 2010

- Shingled Magnetic Recording (SMR), HGST, Inc., 2015

- The Road to Helium, HGST, Inc., 2015

- Research paper about perspective usage of magnetic photoconductors in magneto-optical data storage.