Haplogroup X (mtDNA)

| Haplogroup X | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Possible time of origin | ~30,000 YBP |

| Ancestor | N |

| Descendants | X1, X2 |

| Defining mutations | 73, 7028, 11719, 12705, 14766, 16189, 16223, 16278[1] |

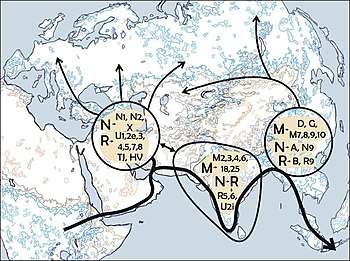

Haplogroup X is a human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroup. It is found in America, Europe, Western Asia, North Africa, and the Horn of Africa.

Origin

The genetic sequences of haplogroup X diverged originally from haplogroup N. They subsequently further diverged thousands of years ago,[2] forming two sub-groups, X1 and X2.

Distribution

Haplogroup X is found in approximately 7% of native Europeans,[3] and 3% of all Native Americans from North America.[4]

Overall, haplogroup X is found in around 2% of the population of Europe, the Near East and North Africa. It is especially common among Egyptians inhabiting El-Hayez oasis (14.3%).[5]

The X1 subclade is much less frequent, and is largely restricted to North Africa, the Horn of Africa and the Near East.

Sub-group X2 appears to have undergone extensive population expansion and dispersal around or soon after the Last Glacial Maximum, about 21,000 years ago. It is more strongly present in the Near East, the Caucasus, and Southern Europe and somewhat less strongly present in the rest of Europe. Particular concentrations appear in Georgia (8%), Orkney (in Scotland) (7%), and amongst the Israeli Druze community (27%). Subclades X2a and X2g are found in North America, but are not present in native South Americans.[6] Many of the early carriers of haplogroup X2a were found in eastern maritime Canada, a prime theoretical landing location for Solutreans. This encouraged adherents to the Solutrean hypothesis. However, more recent discoveries of haplogroup X2a and subgroups have been more widely geographically dispersed. Neither is there a path or ancestral form of X2a found in Europe or the Middle East.

Haplogroup X has been found among ancient Egyptian mummies excavated at the Abusir el-Meleq archaeological site in Middle Egypt, which date from the Pre-Ptolemaic/late New Kingdom and Roman periods.[7] Fossils excavated at the Late Neolithic site of Kelif el Boroud (Kehf el Baroud) in Morocco, which have been dated to around 3,000 BCE, have also been observed to carry the X2 subclade.[8]

Haplogroup X has been found in various other fossils that were analysed for ancient DNA, including specimens associated with the Alföld Linear Pottery (X2b-T226C, Garadna-Elkerülő út site 2, 1/1 or 100%), Linearbandkeramik (X2d1, Halberstadt-Sonntagsfeld, 1/22 or ~5%), and Iberia Chalcolithic (X2b, La Chabola de la Hechicera, 1/3 or 33%; X2b, El Sotillo, 1/3 or 33%; X2b, El Mirador Cave, 1/12 or ~8%) cultures.[9]

Druze

The greatest frequency of haplogroup X is observed in the Druze, a minority population in Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria, as much in X1 (16%) as in X2 (11%).[10] The Druze also have much diversity of X lineages. This pattern of heterogeneous parental origins is consistent with Druze oral tradition. The Galilee Druze represent a population isolate, so their combination of a high frequency and diversity of X signifies a phylogenetic refugium, providing a sample snapshot of the genetic landscape of the Near East prior to the modern age.[11]

North America

Haplogroup X is also one of the five haplogroups found in the indigenous peoples of the Americas.[12] (namely, X2a subclade).

Although it occurs only at a frequency of about 3% for the total current indigenous population of the Americas, it is a bigger haplogroup in northern North America, where among the Algonquian peoples it comprises up to 25% of mtDNA types.[13][14] It is also present in lesser percentages to the west and south of this area—among the Sioux (15%), the Nuu-chah-nulth (11%–13%), the Navajo (7%), and the Yakama (5%).[15]

Unlike the four main Native American mtDNA haplogroups (A, B, C, D), X is not strongly associated with East Asia. The main occurrence of X in Asia discovered so far is in the Altai people in Siberia.[16] and detailed examination[10] The Altaian sequences are all almost identical (haplogroup X2e), suggesting that they arrived in the area probably from Transcaucasia more recently than 5000 BP (like some other haplogroups as well).

One theory of how the X Haplogroup ended up in North America is that the people carrying it migrated from central Asia along with the A, B, C, and D Haplogroups, from an ancestor from the Altai Region of Central Asia.[17] Two sequences of haplogroup X2 were sampled further east of Altai among the Evenks of Central Siberia.[10] These two sequences belong to X2* and X2b. It is uncertain if they represent a remnant of the migration of X2 through Siberia or a more recent input.[17]

This relative absence of haplogroup X2 in Asia is one of the major factors used to support the Solutrean hypothesis. However, the New World haplogroup X2a is as different from any of the Old World X2b, X2c, X2d, X2e, and X2f lineages as they are from each other, indicating an early origin "likely at the very beginning of their expansion and spread from the Near East".[17]

The Solutrean hypothesis postulates that haplogroup X reached North America with a wave of European migration about 20,000 BP by the Solutreans,[18][19] a stone-age culture in south-western France and in Spain, by boat around the southern edge of the Arctic ice pack.

In a 2008 article in the American Journal of Human Genetics, a group of researchers in Brazil (except for David Glenn Smith, of U.C. Davis) argue against the Solutrean hypothesis, stating:

"Our results strongly support the hypothesis that haplogroup X, together with the other four main mtDNA haplogroups, was part of the gene pool of a single Native American founding population; therefore they do not support models that propose haplogroup-independent migrations, such as the migration from Europe posed by the Solutrean hypothesis ... Here we show, by using 86 complete mitochondrial genomes, that all Native American haplogroups, including haplogroup X, were part of a single founding population, thereby refuting multiple-migration models." [15]

An abstract in a 2012 issue of the American Journal of Physical Anthropology states that

"The similarities in ages and geographical distributions for C4c and the previously analyzed X2a lineage provide support to the scenario of a dual origin for Paleo-Indians. Taking into account that C4c is deeply rooted in the Asian portion of the mtDNA phylogeny and is indubitably of Asian origin, the finding that C4c and X2a are characterized by parallel genetic histories definitively dismisses the controversial hypothesis of an Atlantic glacial entry route into North America."[20]

A 2015 report re-evaluates the evidence. Stating the possibility that evidence might be uncovered that supports a trans-Atlantic migration, they state that

"X2a has not been found anywhere in Eurasia, and phylogeography gives us no compelling reason to think it is more likely to come from Europe than from Siberia. Furthermore, analysis of the complete genome of Kennewick Man, who belongs to the most basal lineage of X2a yet identified, gives no indication of recent European ancestry and moves the location of the deepest branch of X2a to the West Coast, consistent with X2a belonging to the same ancestral population as the other founder mitochondrial haplogroups. Nor have any high-resolution studies of genome-wide data from Native American populations yielded any evidence of Pleistocene European ancestry or trans-Atlantic gene flow."[21]

Subclades

Tree

This phylogenetic tree of haplogroup X subclades is based on the paper by Mannis van Oven and Manfred Kayser Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation[1] and subsequent published research.

- X

- X1

- X1a

- X1a1

- X1b

- X1a

- X2

- X2a

- X2a1

- X2a1a

- X2a1b

- X2a2

- X2a1

- X2b

- X2b1

- X2b2

- X2b3

- X2b4

- X2c

- X2c1

- X2c2

- X2d

- X2e

- X2e1

- X2e1a

- X2e1a1

- X2e1a1a

- X2e1a1

- X2e1a

- X2e2

- X2e2a

- X2e1

- X2f

- X2g

- X2h

- X2a

- X1

Popular culture

In his popular book The Seven Daughters of Eve, Bryan Sykes named the originator of the European-American subset of this mtDNA haplogroup - corresponding to X2 - "Xenia".

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Haplogroup X (mtDNA). |

- Genealogical DNA test

- Genetic Genealogy

- Human mitochondrial genetics

- Population Genetics

- Human mitochondrial DNA haplogroups

- Indigenous American genetic studies

- Kennewick man

|

Phylogenetic tree of human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mitochondrial Eve (L) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L0 | L1–6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L1 | L2 | L3 | L4 | L5 | L6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M | N | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CZ | D | E | G | Q | O | A | S | R | I | W | X | Y | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C | Z | B | F | R0 | pre-JT | P | U | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HV | JT | K | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| H | V | J | T | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- 1 2 van Oven M, Kayser M (Feb 2009). "Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation". Human Mutation. 30 (2): E386–94. doi:10.1002/humu.20921. PMID 18853457.

- ↑ Soares, Pedro et al 2009, Correcting for Purifying Selection: An Improved Human Mitochondrial Molecular Clock. and its Supplemental Data. Archived 29 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine. The American Journal of Human Genetics, Volume 84, Issue 6, 740-759, 4 June 2009

- ↑ Bryan Sykes (2001). The Seven Daughters of Eve. London; New York: Bantam Press. ISBN 0393020185.

- ↑ Malhi and Smith, Brief Communication: Haplogroup X Confirmed in Prehistoric North America, American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Volume 119, Issue 1, (September 2002), Pages 84-86.

- ↑ Martina Kujanova; Luisa Pereira; Veronica Fernandes; Joana B. Pereira; Viktor Cerny (2009). "Near Eastern Neolithic Genetic Input in a Small Oasis of the Egyptian Western Desert". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 140 (2): 336–346. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21078. PMID 19425100.

- ↑ Perego UA (2009). "Distinctive Paleo-Indian Migration Routes from Beringia Marked by Two Rare mtDNA Haplogroups". Current Biology. 19: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.11.058.

- ↑ Schuenemann, Verena J.; et al. (2017). "Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods". Nature Communications. 8: 15694. doi:10.1038/ncomms15694. PMC 5459999. PMID 28556824.

- ↑ Fregel; et al. (2018). "Ancient genomes from North Africa evidence prehistoric migrations to the Maghreb from both the Levant and Europe". bioRxiv 191569.

- ↑ Mark Lipson et al. (2017). "Parallel palaeogenomic transects reveal complex genetic history of early European farmers". Nature. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 Reidla M, Kivisild T, Metspalu E, Kaldma K, Tambets K, Tolk HV, et al. (Nov 2003). "Origin and diffusion of mtDNA haplogroup X". American Journal of Human Genetics. 73 (5): 1178–90. doi:10.1086/379380. PMC 1180497. PMID 14574647.

- ↑ Shlush LI, Behar DM, Yudkovsky G, et al. (2008). "The Druze: a population genetic refugium of the Near East". PLoS ONE. 3: e2105. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002105. PMC 2324201. PMID 18461126.

- ↑ "Dolan DNA Learning Center – Native American haplogroups: European lineage, Douglas Wallace". Dnalc.org. Retrieved 2011-01-28.

- ↑ "The peopling of the Americas: Genetic ancestry influences health". Scientific American.

- ↑ "Learn about Y-DNA Haplogroup Q". Wendy Tymchuk – Senior Technical Editor. Genebase Systems. 2008. Archived from the original (Verbal tutorial possible) on 22 June 2010. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- 1 2 Fagundes NJ, Kanitz R, Eckert R, Valls AC, Bogo MR, Salzano FM, Smith DG, Silva WA, Zago MA, Ribeiro-dos-Santos AK, Santos SE, Petzl-Erler ML, Bonatto SL (Mar 2008). "Mitochondrial population genomics supports a single pre-Clovis origin with a coastal route for the peopling of the Americas". American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (3): 583–92. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.11.013. PMC 2427228. PMID 18313026.

(Click here for PDF Format)

- ↑ Derenko MV, Grzybowski T, Malyarchuk BA, Czarny J, Miścicka-Sliwka D, Zakharov IA (Jul 2001). "The presence of mitochondrial haplogroup x in Altaians from South Siberia". American Journal of Human Genetics. 69 (1): 237–41. doi:10.1086/321266. PMC 1226041. PMID 11410843.

- 1 2 3 Reidla M, Kivisild T, Metspalu E, Kaldma K, Tambets K, Tolk HV, et al. (Nov 2003). "Origin and diffusion of mtDNA haplogroup X". American Journal of Human Genetics. The American Society of Human Genetics. 73 (5): 1178–90. doi:10.1086/379380. PMC 1180497. PMID 14574647.

It is apparent that the Native American haplogroup X mtDNAs derive from X2 by a unique combination of five mutations. It is notable that X2 includes the two complete Native American X sequences that constitute the distinctive X2a clade, a clade that lacks close relatives in the entire Old World, including Siberia. The position of X2a in the phylogenetic tree suggests an early split from the other X2 clades, likely at the very beginning of their expansion and spread from the Near East northeast of the Altai area, haplogroup X sequences were detected in the Tungusic-speaking Evenks, of the Podkamennaya Tunguska basin (Central Siberia). In contrast to the Altaians, the Evenks did not harbor any West Eurasian mtDNA haplogroups other than X. However, neither of the two Evenk X haplotypes showed mutations characteristic of the Native American clade X2a. Instead, one sequence was a member of X2b and the other of X2. Thus, one possible scenario is that several X haplotypes arrived in Siberia from western Asia during the Palaeolithic, but only X2a crossed Beringia and survived in modern Native Americans.

- ↑ "The North Atlantic ice-edge corridor: a possible Palaeolithic route to the New World". Bruce Bradley and Dennis Stanford. World Archaeology 2004 Vol. 36(4):459–478. http://planet.uwc.ac.za/nisl/Conservation%20Biology/Karen%20PDF/Clovis/Bradley%20&%20Stanford%202004.pdf

- ↑ Carey, Bjorn (19 February 2006)."First Americans may have been European.Life Science. Retrieved on 10 August 2007.

- ↑ Hooshiar Kashani B, Perego UA, Olivieri A, Angerhofer N, Gandini F, Carossa V, Lancioni H, Semino O, Woodward SR, Achilli A, Torroni A (Jan 2012). "Mitochondrial haplogroup C4c: a rare lineage entering America through the ice-free corridor?". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 147 (1): 35–9. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21614. PMID 22024980.

- ↑ Raff, Jennifer A.; Bolnick, Deborah A (2015). "Does Mitochondrial Haplogroup X Indicate Ancient Trans-Atlantic Migration to the Americas? A Critical Re-Evaluation". PaleoAmerica: A journal of early human migration and dispersal. 1 (4): 297–304. doi:10.1179/2055556315Z.00000000040. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

External links

- General

- Mannis van Oven's – mtDNA subtree N

- Haplogroup X

- The Presence of Mitochondrial Haplogroup X in Altaians from South Siberia Miroslava V. Derenko, Tomasz Grzybowski, and others

- Ian Logan's DNA Site

- Carolyn Benson's X mtDNA Project at Family Tree DNA

- Spread of Haplogroup X, from National Geographic

- CBC, The Solutrean Hypothesis, and Jennifer Raff, A podcast with Jennifer Raff discussions claims in 2018 linking Haplogroup X to the Solutrean hypothesis

Further reading

- Ribetio-dos-Santos AK, Santos SE, Machado AL, Guapindaia V, Zago MA (Sep 1996). "Heterogeneity of mitochondrial DNA haplotypes in Pre-Columbian Natives of the Amazon region". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 101 (1): 29–37. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199609)101:1<29::AID-AJPA3>3.0.CO;2-8. PMID 8876812.

- Peter N. Jones (2004). American Indian mtDNA, Y Chromosome Genetic Data, and the Peopling of North America. Boulder: Bauu Press. ISBN 978-0-9721349-1-0. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- Easton RD, Merriwether DA, Crews DE, Ferrell RE (Jul 1996). "mtDNA variation in the Yanomami: evidence for additional New World founding lineages". American Journal of Human Genetics. 59 (1): 213–25. PMC 1915132. PMID 8659527.

- Brown MD, Hosseini SH, Torroni A, Bandelt HJ, Allen JC, Schurr TG, Scozzari R, Cruciani F, Wallace DC (Dec 1998). "mtDNA haplogroup X: An ancient link between Europe/Western Asia and North America?". American Journal of Human Genetics. 63 (6): 1852–61. doi:10.1086/302155. PMC 1377656. PMID 9837837.

- Smith DG, Malhi RS, Eshleman J, Lorenz JG, Kaestle FA (Nov 1999). "Distribution of mtDNA haplogroup X among Native North Americans". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 110 (3): 271–84. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199911)110:3<271::AID-AJPA2>3.0.CO;2-C. PMID 10516561.

- Zakharov IA, Derenko MV, Maliarchuk BA, Dambueva IK, Dorzhu CM, Rychkov SY (Apr 2004). "Mitochondrial DNA variation in the aboriginal populations of the Altai-Baikal region: implications for the genetic history of North Asia and America". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1011: 21–35. doi:10.1196/annals.1293.003. PMID 15126280.