Georgian–Seljuk wars

| Georgian–Seljuk wars | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| Seljuq Turks | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Bagrat IV George II David IV Demetrius I George III Tamar the Great George IV |

Mahmud II Ghiyath ad-Din Dawud Toghrul II Ghiyath ad-Din Mas'ud Arslan II Toghrul III Malik-Shah II Kaykhusraw I Suleiman II | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 45,000–90,000 | 250,000–450,000 | ||||||||

Georgian–Seljuk wars, also known as Georgian Reconquista[1] is a long series of battles and military clashes that took place from c. 1048 until 1213, between the Kingdom of Georgia and the different Seljuqid states that occupied most of Transcaucasia. The conflict is preceded by deadly raids in the Caucasus by the Turks in the 11th century, known in Georgian historiography as the Great Turkish Invasion.

Background

In 1048-9, the Seljuk Turks under Ibrahim Yinal made their first incursion in Byzantine frontier region of Iberia. The emperor Constantine IX requested help from the Georgian duke of Liparit IV of Kldekari, whom the Byzantines had aided in his struggle against the Georgian king Bagrat IV. Liparit, who had been fighting on the Byzantine side, was captured at the Battle of Kapetron. Bagrat took advantage of this, and acquired his possessions.

Although the Byzantine Empire and Georgia had centuries-long cultural and religious ties, and the Seljuqs posed a substantial threat to the empire itself, Constantinople’s aggressiveness on the Caucasian political scene contributed to an atmosphere of distrust and recrimination, and prevented the two Christian nations from effective cooperation against the common threat. With assertion of the Georgian Bagratid hegemony in the Caucasus being the cornerstone of Bagrat’s reign, his policy can be understood as the attempt to play the Seljuqs and Byzantines off against one another.[2]

Initial Conflicts: 1060–1080

The second half of the 11th century was marked by the strategically significant invasion of the Seljuq Turks, who by the end of the 1040s had succeeded in building a vast empire including most of Central Asia and Persia. The Seljuqs made their first appearances in Georgia in the 1060s, when the Sultan Alp Arslan laid waste to the south-western provinces of the Georgian kingdom and reduced Kakheti. These intruders were part of the same wave of the Turkish movement which inflicted a crushing defeat on the Byzantine army at Manzikert in 1071.[3]

The Seljuk threat prompted the Georgian and Byzantine governments to seek a closer cooperation. To secure the alliance, Bagrat’s daughter Maria married, at some point between 1066 and 1071, to the Byzantine co-emperor Michael VII Ducas. The choice of a Georgian princess was unprecedented, and it was seen in Georgia as a diplomatic success on Bagrat's side.[4]

On 10 December 1068, Alp Arslan, dissatisfied with the act of the last Caucasian monarch that he had not yet submitted, accompanied by the kings of Lorri and Kakheti as well as the emir of Tbilisi marched against Bagrat again. The provinces of Kartli and Argveti were occupied and pillaged. Bagrat’s long-time rivals, the Shaddadids of Arran, were given compensation: the fortresses of Tbilisi and Rustavi. As soon as Alp Arslan left Georgia, Bagrat recovered Kartli in July 1068. Al-Fadl I b. Muhammad, of the Shaddadids, encamped at Isani (a suburb of Tbilisi on the left bank of the Kura) and with 33,000 men ravaged the countryside. Bagrat defeated him, however, and forced the Shaddadid troops to flight. On the road through Kakheti, Fadl was taken prisoner by the local ruler Aghsartan. At the price of conceding several fortresses on the Iori River, Bagrat ransomed Fadl and received from him the surrender of Tbilisi where he reinstated a local emir on the terms of vassalage.[5]

The last years of Bagrat's reign coincided with what Professor David Marshall Lang described as "the final débacle of eastern Christendom" — the Battle of Manzikert — in which Alp Arslan dealt a crushing defeat to the Byzantine army, capturing the emperor Romanos IV, who soon died in misery. Bagrat IV died the following year, on 24 November 1072, and was buried at the Chkondidi Monastery. The suzerainty over the troubled kingdom of Georgia passed to his son George II.[6] Georgians were able to recover theme of Iberia, by the help of Byzantine governor, Gregory Pakourianos, who began to evacuate the region shortly after the disaster inflicted by the Seljuks on the Byzantine army at Manzikert. On this occasion, George II of Georgia was bestowed with the Byzantine title of Caesar, granted the fortress of Kars and put in charge of the Imperial Eastern limits.

Great Turkish Invasion

Although the Georgians were able to recover from Alp Arslan's invasion, the Byzantine withdrawal from Anatolia brought them in more direct contact with the Seljuqs. In the 1070s, Georgia was twice attacked by the Sultan Malik Shah I, but the Georgian King George II was still able to fight back at times.[7] In 1076 Malik Shah surged into Georgia and reduced many settlements to ruins, from 1079/80 onward, George was pressured into submitting to Malik-Shah to ensure a precious degree of peace at the price of an annual tribute. George's acceptance of the Seljuq suzerainty did not bring a real peace for Georgia. The Turks continued their seasonal movement into the Georgian territory to make use of the rich herbage of the Kura valley and the Seljuq garrisons occupied the key fortresses in Georgia's south.[8] These inroads and settlements had a ruinous effect on Georgia's economic and political order. Cultivated lands were turned into pastures for the nomads and peasant farmers were compelled to seek safety in the mountains.[9]

George II was able to garner the Seljuk military support in his campaign aimed at bringing the eastern Georgian kingdom of Kakheti, which had long resisted the Bagratid attempts of annexation. However, tired with a protracted siege of the Kakhetian stronghold of Vezhini, George abandoned the campaign when snow fell. The Seljuk auxiliaries also lifted the siege and plundered the fertile Iori Valley in Kakheti. Aghsartan I, king of Kakheti, went to the sultan to declare his submission, and in token of loyalty embraced Islam, thus winning a Seljuk protection against the aspirations of the Georgian crown.[10]

George II’s wavering character and incompetent political decisions coupled with the Seljuk yoke brought the Kingdom of Georgia into a profound crisis which climaxed in the aftermath of a disastrous earthquake that struck Georgia in 1088.

Georgian Reconquista

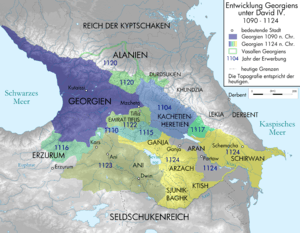

David IV

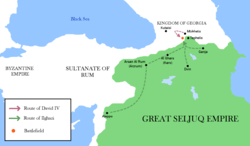

Watching his kingdom slip into chaos, George II ceded the crown to his 16-year-old son David IV in 1089. King David IV proved to be a capable statesman and military commander. As he came of age under the guidance of his court minister, George of Chqondidi, David IV suppressed dissent of feudal lords and centralized the power in his hands to effectively deal with foreign threats. In 1089–1100, he organized small detachments to harass and destroy isolated Seljuk troops and began the resettlement of desolate regions. By 1099 David IV's power was considerable enough that he was able to refuse paying tribute to Seljuqs. In 1104 David’s supporters in the eastern Georgian province of Kakheti, nobles: Baramisdze and Arshiani captured the local king Aghsartan II (1102–1104), a loyal tributary of the Seljuk Sultan Barkiyaruq (c.1092-1105), and reunited the area with the rest of Georgia. Following the annexation of Kakheti, in 1105, David routed a Seljuk punitive force at the Battle of Ertsukhi, leading to momentum that helped him to secure the key fortresses of Samshvilde, Rustavi, Gishi, and Lori between 1110 and 1118.

To strengthen his army, King David launched a major military reform in 1118–1120 and resettled several thousand Kipchaks from the northern steppes to frontier districts of Georgia. In return, the Kipchaks provided one soldier per family, allowing King David to establish a standing army in addition to his royal troops (known as Monaspa). The new army provided the king with a much-needed force to fight both external threats and internal discontent of powerful lords. The Georgian-Kipchak alliance was facilitated by David's earlier marriage to the Khan's daughter. Starting in 1120, King David began a more aggressive policy of expansion. He entered the neighbouring Shirvan and took the town of Qabala. In the winter of 1120–1121 the Georgian troops successfully attacked the Seljuk settlements on the eastern and southwestern approaches to the Transcaucasus. Muslim powers became increasingly concerned about the rapid rise of a Christian state in southern Caucasia. In 1121, Sultan Mahmud b. Muhammad (c. 1118–1131) declared a holy war on Georgia. However, 12 August 1121, King David routed the enemy army on the fields of Didgori, with fleeing Seljuq Turks being run down by pursuing Georgian cavalry for several days. A huge amount of booty and prisoners were captured by David's army, which had also secured Tbilisi, the last Muslim enclave remaining from the Arab occupation, in 1122 and moved the Georgian capital there and inaugurated Georgia's Golden Age.[11]

In 1123, David’s army liberated Dmanisi, the last Seljuk stronghold in southern Georgia. In 1124, David finally conquered Shirvan and took the Armenian city of Ani from the Muslim emirs, thus expanding the borders of his kingdom to the Araxes basin. Armenians met him as a liberator providing some auxiliary force for his army.

Demetrius I

The kingdom continued to flourish under Demetrius I, the son of David. Although his reign saw a disruptive family conflict related to royal succession, Georgia remained a centralized power with a strong military. As soon as, he ascended to the throne, the neighbouring Muslim rulers began attacking Georgia from all sides. The Seljuqid sultans fought to restore the rule of the Shirvanshahs. Shirvan's large Muslim population rose against Georgia. This probably happened in 1129 or 1130, when Demetrius restored the Shirvanshahs to power in Shirvan, installing on the throne Manuchihr II, the husband of his daughter Rusudan. Shirvanshahs had to provide the Georgian king with troops whenever the latter demanded it.

In 1130 Georgia was attacked by the Sultan of Ahlat, Shah-Armen Sökmen II (c.1128-1183). This war was started by the passage of Ani into the hands of the Georgians; Demetrius I had to compromise and give up Ani to Fadl ibn Mahmud on terms of vassalage and inviolability of the Christian churches. In 1139, Demetrius raided the city of Ganja in Arran. He brought the iron gate of the defeated city to Georgia and donated it to Gelati Monastery at Kutaisi. Despite this brilliant victory, Demetrius could hold Ganja only for a few years.[12][13] In reply to this, the sultan of Eldiguzids attacked Ganja several times, and in 1143 the town again jell to the sultan. According to Mkhitar Gosh, Demetrius ultimately gained possession of Ganja, but, when he gave his daughter in marriage to the sultan, he presented the latter with the town as dowry, and the sultain appointed his own emir to rule it.

Fadl's successor, Fakr al-Din Shaddad, a Shaddadid emir of Ani asked for Saltuk's daughter's hand, however Saltuk refused him. This caused a deep hatred in Shaddad towards Saltuk. In 1154 he planned a plot and formed a secret alliance with the Demetrius I. While a Georgian army waited in ambush, he offered tribute to Saltukids, ruler of Erzerum and asked the latter to acccept him as a vassal. In 1153-1154 Emir Saltuk II marched on Ani, but Shaddad informed his suzerain, the King of Georgia, of this. Demetrius marched to Ani, defeated and captured the emir. At the request of neighbouring Muslim rulers and released him for a ransom of 100,000 dinars, paid by Saltuk's sons in law and Saltuk swore not to fight against the Georgians he returned home.[14]

George III

Demetrius was succeeded by his son George III in 1156, beginning a stage of more offensive foreign policy. The same year he ascended to the throne, George launched a successful campaign against the Shah-Armens. It may be said that the Shah-Armen took part in almost all the campaigns undertaken against Georgia between 1130s to 1160s. Moreover, Shah-Armens enlisted the assistance of Georgian feudals disaffected with the Georgian monarchs and gave them asylum. In 1156 the Ani's Christian population rose against the emir Fakr al-Din Shaddad, and turned the town over to his brother Fadl ibn Mahmud. But Fadl, too, apparently could not satisfy the people of Ani, and this time the town was offered to the George III, who took advantage of this offer and subjugated Ani, appointing his general Ivane Orbeli as its ruler in 1161.

A coalition consisting of the ruler of Ahlat, Shah-Armen Sökmen II, the ruler of Diyarbekir, Kotb ad-Din il-Ghazi, Al-Malik of Erzerum, and others was formed as soon as the Georgians seized the town, but the latter defeated the allies. He then marched against one of the members of the coalition, the king of Erzerum, and in the same year, 1161, defeated and made him prisoner, but then released him for a large ransom. The capture of Ani and the defeat of the Saltukid-forces enabled the Georgian king to march on Dvin. The following year in August/September 1162, Dvin was temporarily occupied and sacked, the non-Christian population was pillaged and the Georgian troops returned home loaded with booty. The king appointed Ananiya, a member of the local feudal nobility to govern the town.

A coalition of Muslim rulers led by Shams al-Din Eldiguz, ruler of Adarbadagan and some other regions, embarked upon a campaign against Georgia in early 1163. He was joined by the Shah-Armen Sökmen II, Ak-Sunkur, ruler of Maragha, and others. With an army of 50,000 troops they marched on Georgia. The Georgian army was defeated. The enemy took the fortress of Gagi, laid waste as far as the region of Gagi and Gegharkunik, seized prisoners and booty, and then moved to Ani. The Muslim rulers were jubilant, and they prepared for a new campaign. However, this time they were forestalled by George III, who marched into Arran at the beginning of 1166, occupied a region extending to Ganja, devastated the land and turn back with prisoners and booty.

There seemed to be no end to the war between George III and atabeg Eldiguz. But the belligerents were exhausted to such an extent that Eldiguz proposed an armistice. George had no choice but to make peace. He restored Ani to its former rulers, the Shaddadids, who became his vassals. The Shaddadids, ruled the town for about 10 years, but in 1174 King George took the Shahanshah ibn Mahmud as a prisoner and occupied Ani once again. Ivane Orbeli, was appointed governor of the town.

In 1177 George III faced the revolt of House of Orbeli. Ivane decided to request aid from neighbouring kingdoms. In particular, they requested aid from Shah-Armens and Eldiguzids, but no assistance was forthcoming. George III was able to crush the revolt and embarked on a crackdown campaign on the defiant aristocratic clans; Ivane Orbeli was put to death and the surviving members of his family were driven out of Georgia. Sargis I Mkhargrdzeli was appointed as a governor of Ani. In 1178, George III appointed his daughter and heiress Tamar as heir apparent and co-ruler to forestall any dispute after his death. However, he remained co-regent until his death in 1184.

Tamar the Great

The successes of his predecessors were built upon by Queen Tamar, daughter of George III, who became the first female ruler of Georgia in her own right and under whose leadership the Georgian state reached the zenith of power and prestige in the Middle Ages. Tamar was successful in neutralizing this opposition and embarked on an energetic foreign policy aided by the decline of the hostile Seljuq Turks. Relying on a powerful military élite, Tamar was able to build an empire which dominated the Caucasus until its collapse under the Mongol attacks within two decades after Tamar's death.

Once Tamar succeeded in consolidating her power and found a reliable support in David Soslan, the Mkhargrdzeli, Toreli, and other noble families, she revived the expansionist foreign policy of her predecessors. Repeated occasions of dynastic strife in Georgia combined with the efforts of regional successors of the Great Seljuq Empire, such as the Eldiguzids, Shirvanshahs, and the Ahlatshahs, had slowed down the dynamic of the Georgians achieved during the reigns of Tamar's great-grandfather, David IV, and her father, George III. However, the Georgians became again active under Tamar, more prominently in the second decade of her rule.

Early in the 1190s, the Georgian government began to interfere in the affairs of the Eldiguzids and of the Shirvanshahs, aiding rivaling local princes and reducing Shirvan to a tributary state. The Eldiguzid atabeg Abu Bakr attempted to stem the Georgian advance, but suffered a defeat at the hands of David Soslan at the Battle of Shamkor[15] and lost his capital to a Georgian protégé in 1195. Although Abu Bakr was able to resume his reign a year later, the Eldiguzids were only barely able to contain further Georgian forays.[16][17]

The question of liberation of Armenia remained of prime importance in Georgia's foreign policy. Tamar's armies led by two Christianised Kurdish[18] generals, Zakare and Ivane Mkhargrdzeli overran fortresses and cities towards the Ararat Plain, reclaiming one after another fortresses and districts from local Muslim rulers.

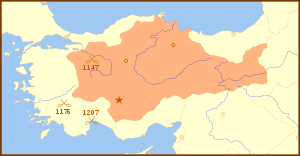

Alarmed by the Georgian successes, Süleymanshah II, the resurgent Seljuqid sultan of Rûm, rallied his vassal emirs and marched against Georgia, but his camp was attacked and destroyed by David Soslan at the Battle of Basian in 1203 or 1204. The chronicler of Tamar describes how the army was assembled at the rock-hewn town of Vardzia before marching on to Basian and how the queen addressed the troops from the balcony of the church.[19] Exploiting her success in this battle, between 1203-1205 Georgians seized the town of Dvin[20] and entered Akhlatshah possessions twice and subdued the emir of Kars (vassal of the Saltukids in Erzurum), Akhlatshahs, the emirs of Erzurum and Erzincan. In 1206 the Georgian army, under the command of David Soslan, captured Kars and other fortresses and strongholds along the Araxes. This campaign was evidently started because the ruler of Erzerum refused to submit to Georgia. The emir of Kars requested aid from the Akhlatshahs, but the latter was unable to respond, it was soon taken over by the Ayyubid Sultanate In 1207.

In 1209, the brothers Mkhargrzeli laid waste to Ardabil – according to the Georgian and Armenian annals – as a revenge for the local Muslim ruler's attack on Ani and his massacre of the city's Christian population.[21] In a great final burst, the brothers led an army marshaled throughout Tamar's possessions and vassal territories in a march, through Nakhchivan and Julfa, to Marand, Tabriz, and Qazvin in northwest Iran, pillaging several settlements on their way.[21] Georgians reached countries where nobody had heard of either their name or existence. These victories brought Georgia to the summit of its power and glory, establishing a pan-Caucasian Empire that extended from the Black Sea to the Caspian and from the Caucasus Mountains to Lake Van.

Consequences

George IV continued Tamar's policy. He put down the revolts in neighbouring Muslim vassal states in the 1210s and began preparations for a large-scale campaign against Jerusalem to support the Crusaders in 1220. However, the Mongols approach to the Georgian borders made the Crusade plan unrealistic. The first Mongol expedition defeated Georgian armies in 1221–1222. George IV died fighting them in 1223 and his sister Rusudan made a desperate alliance against Mongols when she and her daughter Tamar married to Seljuk princes of Erzurum and Sultanate of Rum. The former enemies were now the closest allies (Battle of Köse Dağ) but that did not prevent the Mongol advance.

See also

References

- ↑ René Grousset, L'Empire du Levant : Histoire de la Question d'Orient, 1949, p. 417

- ↑ Lynda Garland & Stephen Rapp. Mary 'of Alania': Woman and Empress Between Two Worlds, pp. 94–5. In: Lynda Garland (ed., 2006), Byzantine Women: Varieties of Experience, 800–1200. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 0-7546-5737-X.

- ↑ Suny 1994, p. 34

- ↑ Lynda Garland with Stephen H. Rapp Jr. (2006). Mart'a-Maria 'of Alania'. An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors. Retrieved on 24 December 2007.

- ↑ V. Minorsky, "Tiflis", p. 754. In: M. Th. Houtsma, E. van Donzel (1993), E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936. Brill, ISBN 90-04-08265-4.

- ↑ Lang, David Marshall (1966), The Georgians, p. 111. Praeger Publishers.

- ↑ Thomson 1996, p. 310

- ↑ Allen 1932, p. 98

- ↑ Suny 1994, p. 34

- ↑ Lordkipanidze, Mariam Davydovna; Hewitt, George B. (1987), Georgia in the XI-XII Centuries, pp. 76–78. Ganatleba Publishers: Tbilisi.

- ↑ (in Georgian) Javakhishvili, Ivane (1982), k'art'veli eris istoria (The History of the Georgian Nation), vol. 2, pp. 184-187. Tbilisi State University Press.

- ↑ Rayfield, Donald (2013). Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia. Reaktion Books. p. 100. ISBN 978-1780230702.

- ↑ Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 259. ISBN 978-1442241466.

- ↑ Prof. Yaşar Yüce-Prof. Ali Sevim: Türkiye tarihi Cilt I, AKDTYKTTK Yayınları, İstanbul, 1991, p 149-150

- ↑ Suny 1994, p. 39.

- ↑ Luther, Kenneth Allin. "Atābākan-e Adārbāyĵān", in: Encyclopædia Iranica (Online edition). Retrieved on 2006-06-26.

- ↑ Lordkipanidze & Hewitt 1987, p. 148.

- ↑ Kuehn 2011, p. 28.

- ↑ Eastmond 1998, p. 121; Lordkipanidze & Hewitt 1987, pp. 150–151.

- ↑ Lordkipanidze & Hewitt 1987, p. 150.

- 1 2 Lordkipanidze & Hewitt 1987, p. 154.