Frederic Edwin Church

| Frederic Edwin Church | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Frederic Edwin Church | |

| Born |

May 4, 1826 Hartford, Connecticut, United States |

| Died |

April 7, 1900 (aged 73) New York City, New York, United States |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Landscape painting |

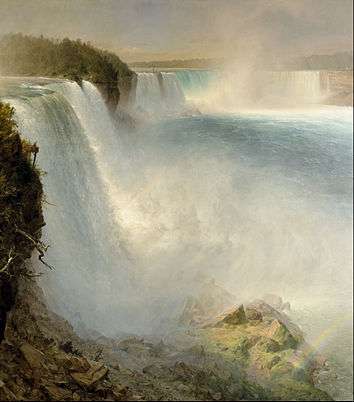

| Notable work | Niagara, The Heart of the Andes |

| Movement | Hudson River School |

Frederic Edwin Church (May 4, 1826 – April 7, 1900) was an American landscape painter born in Hartford, Connecticut. He was a central figure in the Hudson River School of American landscape painters, best known for painting large landscapes, often depicting mountains, waterfalls, and sunsets. Church's paintings put an emphasis on realistic detail, dramatic light, and panoramic views. He debuted some of his major works in single-painting exhibitions to a paying and often enthralled audience in New York City. In his prime, he was the most famous painter in the United States.

Biography

Beginnings

Frederic Edwin Church was a direct descendant of Richard Church, a Puritan pioneer from England who accompanied Thomas Hooker on the original journey through the wilderness from Massachusetts to what would become Hartford, Connecticut.[1] Church was the son of Eliza (1796–1883) and Joseph Church (1793–1876). Frederic had two sisters and no surviving brothers. His father was successful in business as a silversmith and jeweler and was a director at several financial firms. The family's wealth allowed Frederic to pursue his interest in art from a very early age. In 1844, aged 18, Church became the pupil of landscape artist Thomas Cole[2] in Catskill, New York after Daniel Wadsworth, a family neighbor and founder of the Wadsworth Athenaeum, introduced the two. Church studied with him for two years; by this time his talent was more than evident. During his time with Cole, he travelled around New England and New York to make sketches, visiting East Hampton, Long Island, Catskill Mountain House, The Berkshires, New Haven, and Vermont.[3] His first recorded sale of a painting was in 1846 to Hartford's Wadsworth Athenaeum for $130; it was a pastoral depicting Hooker's journey in 1636. In 1848, he was elected as the youngest Associate of the National Academy of Design and was promoted to full member the following year. He took his own students: William James Stillman, in 1848, and Jervis McEntee in 1850.[3]

Style and influences

Romanticism was prominent in Britain and France in the early 1800s as a counter-movement to the rationalism of the Age of Enlightenment. Artists of the Romantic period often depicted nature in idealized scenes that depicted the richness and beauty of nature, sometimes with emphasis on its grand scale. This tradition carried on in the works of Church, who idealizes an uninterrupted nature, highlighted by his excruciatingly detailed art. The emphasis on nature is encouraged by low horizontal lines and a preponderance of sky. Church usually "hid" his brushstrokes so that the painting surface was smooth and the painter's "personality" seemingly absent.

Church was the product of the second generation of the Hudson River School, a movement in American landscape art founded by his teacher Thomas Cole.[5] Both Cole and Church were devout Protestants, and the latter's beliefs played a role in his paintings, especially his early canvases.[6] Hudson River School paintings were characterized by their focus on traditional pastoral settings, especially the Catskill Mountains, and their Romantic qualities. They attempted to capture the wild realism of an unsettled America that was quickly disappearing, and the appreciation of natural beauty. His American frontier landscapes show the "expansionist and optimistic outlook of the United States in the mid-nineteenth century." Church differed from Cole in the topics of his paintings: he preferred natural and often majestic scenes over Cole's propensity towards allegory—though Church's work has increasingly been re-examined in terms of themes and meanings.

The Prussian explorer and scientist Alexander von Humboldt was a major influence on Church. In his Kosmos, Humboldt put forth a vision of the interconnectedness of science, the natural world, and spiritual concerns. Kosmos, which Church owned, dedicated a chapter to landscape painting; Humboldt gave an important role to the visual artist in "scientifically" portraying the diversity of nature, especially in the New World. As Charles Darwin's theory of evolution began to overturn Humboldt's ideas of unity in the 1860s, art historians have examined how Church's painting responded to this disruption in Church's world view.

The English art critic John Ruskin was another important influence on Church. In Ruskin's Modern Painters, he emphasizes the close observation of nature: "the imperative duty of the landscape painter [is] to descend to the lowest details with undiminished attention. Every class of rock, every kind of earth, every form of cloud, must be studied with equal industry, and rendered with equal precision." This attention to detail must be combined with the artist's interpretation, impressions, and imagination to achieve great art.[7]

Some of Church's paintings relate to, and influenced, the luminist landscape style as well. Luminist art tends to emphasize horizontals, use non-diffuse light, and hide brushstrokes such that the painter's presence, or "personality", is less apparent to the viewer. An exhibition book considers Church's Morning in the Tropics and Twilight in the Wilderness to highlight the style's "meticulous draftsmanship and intense colors", while Cotopaxi and The Parthenon "exemplify the style ... in their panoramic structure".[8] Nevertheless, Church is not considered a primarily luminist artist.[9]

Career

Church began his career by painting classic Hudson River School scenes of New York and New England, but by 1850, he had settled in New York. He exhibited his art at the American Art Union, the Boston Art Club, and (most impressively for a young artist) the National Academy of Design. His method consisted of creating paintings in his studio based on sketches in nature. In the earlier years of his career, Church's style was reminiscent of that of his teacher, Thomas Cole, and epitomized the Hudson River School's founding styles. As his style progressed he departed from Cole's approach: he painted in more elaborate detail and his compositions became more adventurous in format, sometimes with dramatic light effects.

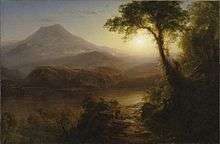

Church made two trips to South America in 1853 and 1857 and stayed predominantly in Quito, Ecuador. The first trip was with businessman Cyrus West Field, who financed the voyage, hoping to use Church's paintings to lure investors to his South American ventures. Church was inspired by Alexander von Humboldt's exploration of the continent in the early 1800s; Humboldt had challenged artists to portray the "physiognomy" of the Andes. After Humboldt's Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of America was published in 1852, Church jumped at the chance to travel and study in Humboldt's footsteps. When Church returned in 1857 with painter Louis Rémy Mignot, he added to his landscape paintings of the area. After both trips, Church had produced a number of landscapes of Ecuador and the Andes, such as The Andes of Ecuador (1855), Cayambe (1858), The Heart of the Andes (1859), and Cotopaxi (1862). The Heart of the Andes, Church's most famous painting, pictures several elements of topography combined into an idealistic, broad portrait of nature. The painting was very large, yet highly detailed; every species of plant and animal is identifiable and numerous climate zones appear at once.

As he had with Niagara before, Church debuted The Heart of the Andes in a single-painting exhibition in New York City. Thousands of people paid to see the painting, with the painting's huge floor-based frame playing the part of a window looking out on the Andes. The audience sat on benches to view the piece, sometimes using opera glasses to get close, and Church strategically darkened the room with a spotlight on the painting. The work was an instant success. Church eventually sold it for $10,000, at that time the highest price ever paid for a work by a living American artist.

During the Civil War, Church was inspired to paint Our Banner in the Sky, from which a lithograph was made and sold to benefit the families of Union soldiers.[10] In 1863, he was elected an Associate Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[11]

By 1860, Church was the most renowned American artist. In his prime, Church was a commercial as well as an artistic success. Church's art was very lucrative; he was reported to be worth half a million dollars at his death in 1900.

Family, later travels, and Olana

In 1860, Church bought a farm in Hudson, New York and married Isabel Carnes. Both Church's first son and daughter died in March 1865 of diphtheria; he and his wife started a new family with the birth of Frederic Joseph in 1866. When the couple had a family of four children, they began to travel together.

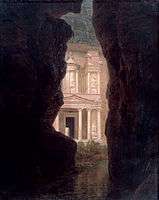

In 1867, Church began the longest period of travel of his career. In the fall of 1867 he and his family went to Europe, moving through London and Paris fairly quickly. From Marseille they went to Alexandria, Egypt, but Church did not visit the pyramids, perhaps being afraid to leave his family alone. Passing through Jaffa, they arrived at Beirut, where they spent four months. They stayed with American missionaries, including David Stuart Dodge. In February 1868 Church travelled with Dodge to the city of Petra, by camel from Jerusalem. Later that spring the family visited Damascus and Baalbek, then sailed the Aegean Sea with a stop in Constantinople. Back in southern Europe by summer, they wintered in Rome, where Church's wife gave birth to a son. A two-week stay in Athens ended the journey in April 1869.[12]

Before leaving on that trip, Church purchased the 18 acres (7.3 ha) on the hilltop above his Hudson farmland, which he had long wanted because of its magnificent views of the Hudson River and the Catskills. In 1870, he began the construction of a Persian-inspired mansion on the hilltop and the family moved into the home in the summer of 1872. Today this land is conserved as the Olana State Historic Site. Richard Morris Hunt was consulted early on in the plans for the mansion at Olana, but after the Churches' trip, the English-born American architect Calvert Vaux was hired to complete the project.[2] Church was deeply involved in the process, even completing his own architectural sketches for its design. This highly personal and eclectic castle incorporated many of the design ideas that he had acquired during his travels. He devoted much of his energies during the final twenty years of his life to his house at Olana.

Church had been enormously successful as an artist. In his last decades, illness limited Church's ability to paint. By 1876, Church was stricken with rheumatoid arthritis, making painting difficult. He eventually painted with his left hand and continued to produce works, although at a much slower pace. He still taught painting as Cole had before him; two students were Walter Launt Palmer and Howard Russell Butler. In later life he often wintered in Mexico, where he taught Butler.[13]

Church died on April 7, 1900 in New York City. He is buried in Spring Grove Cemetery, Hartford, Connecticut.[14]

Legacy

%2C_1861_(color).jpg)

In the last decades of his life Church's fame dwindled, and by his death in 1900 there was little interest in his work. His paintings were seen as part of an "old-fashioned and discredited" school that was too devoted to details.[15] His reputation improved with a 1945 exhibition devoted to the Hudson River School at the Art Institute of Chicago, and that year the Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin revisited the original reception of The Heart of the Andes.[16] In 1960 art historian David C. Huntington completed a dissertation on Church that explored his influences and milieu. By 1966 he had written a monograph on Church and organized the first exhibition devoted to Church since his death,[17] for the National Collection of Fine Arts. Church's legacy was rekindled; American museums began to acquire his works, and by 1979 Church's The Icebergs sold for $2.5 million, then the third-highest auction for any work of art.[18] The next year the National Gallery of Art held a major exhibition, American Light: The Luminist Movement, 1825–1875, which positioned Church as the leading American painter of his time.[15]

Olana State Historic Site is now owned and operated by the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, Taconic Region, and receives extensive support from The Olana Partnership, a private, non-profit organization.

Gallery

Cotopaxi, 1855

Cotopaxi, 1855 Cross in the Wilderness, 1857

Cross in the Wilderness, 1857

Morning in the Tropics, ca. 1858, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Morning in the Tropics, ca. 1858, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.jpg) Twilight in the Wilderness, 1860, Cleveland Museum of Art

Twilight in the Wilderness, 1860, Cleveland Museum of Art Oosisoak, 1861

Oosisoak, 1861 Rainy Season in the Tropics, 1866, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Rainy Season in the Tropics, 1866, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives, 1870, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives, 1870, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art_Frederic_Edwin_Church.jpg) The Parthenon, 1871, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Parthenon, 1871, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Passing Shower in the Tropics, 1872, Princeton University Art Museum

Passing Shower in the Tropics, 1872, Princeton University Art Museum El Khasne Petra, 1874, Olana State Historic Site

El Khasne Petra, 1874, Olana State Historic Site The Aegean Sea, c. 1877, Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Aegean Sea, c. 1877, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Notes

- ↑ Howat, 3

- 1 2 "Frederic Edwin Church". Collection. Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- 1 2 Kelly, 158–159

- ↑ Avery, 17

- ↑ "Master, Mentor, Master: Thomas Cole & Frederic Church". Thomas Cole National Historic Site. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ↑ Avery, 12

- ↑ Rosenbaum, Julia B. (2015). "Frederic Edwin Church in an Era of Expedition". American Art. 29 (2): 26–34.

- ↑ Wilmerding, 17

- ↑ Wilmerding, 120

- ↑ "Rally 'Round The Flag – Frederic Edwin Church and The Civil War". The Olana Partnership. 2011. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- ↑ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter C" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

- ↑ Davis, John (1987). "Frederic Church's 'Sacred Geography'". Smithsonian Studies in American Art. 1 (1): 79–96.

- ↑ Burke, Doreen Bolger (1980). American Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Vol. 3. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 174, 284. ISBN 9780870992445.

- ↑ McEnroe, Colin (July 12, 1995). "A Tidy Resting Place For Famed Artist". Hartford Courant.

- 1 2 Kelly, 12–14

- ↑ See: Gardner, Albert Ten Eyck (1945). "Scientific Sources of the Full-Length Landscape: 1850". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 4 (2): 59–65. doi:10.2307/3257164.

- ↑ Harvey, 12

- ↑ Harvey, 24

Sources

- Avery, Kevin J. (1993). Church's Great Picture: The Heart of the Andes. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-9994925193.

- Harvey, Eleanor Jones; Church, Frederic Edwin (2002). The Voyage of the Icebergs: Frederic Church's Arctic Masterpiece. Dallas Museum of Art. ISBN 9780300095364.

- Howat, John K.; Church, Frederic Edwin (2005). Frederic Church. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300109887.

- Kelly, Franklin (1989). Frederic Edwin Church. National Gallery of Art. ISBN 978-0874744583.

- Wilmerding, John (1989). American Light: The Luminist Movement, 1850–1875. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691040745.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Frederic Edwin Church. |

- Frederic Edwin Church works at National Gallery of Art

- Timeline of Art History Metropolitan Museum of Art

- The Olana Partnership

- American Paradise: The World of the Hudson River School, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Church (see index)

- Art and the empire city: New York, 1825–1861, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (full PDF), which contains material on Church

- Lyrics to the song "Olana" by Marc Cohn, about Church and the Olana estate, from Church's perspective.

- Art Renewal.org

- Frederic Edwin Church Gallery at MuseumSyndicate