Hans Christian Andersen

| Hans Christian Andersen | |

|---|---|

Photograph taken by Thora Hallager, 1869 | |

| Born |

2 April 1805 Odense, Funen, Kingdom of Denmark–Norway |

| Died |

4 August 1875 (aged 70) Østerbro, Copenhagen, Kingdom of Denmark |

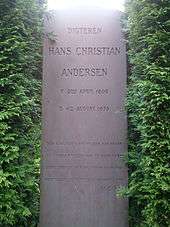

| Resting place | Assistens Cemetery, Copenhagen |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Language | Danish |

| Period | Danish Golden Age |

| Genres | Children's literature, travelogue |

| Notable works |

The Little Mermaid The Ugly Duckling The Emperor's New Clothes |

|

| |

| Signature |

|

| Website | |

| Hans Christian Andersen Centre | |

Hans Christian Andersen (/ˈændərsən/; Danish: [hanˀs ˈkʁæsdjan ˈɑnɐsn̩] (![]()

Andersen's fairy tales, of which no fewer than 3381 works[1] have been translated into more than 125 languages,[2] have become culturally embedded in the West's collective consciousness, readily accessible to children, but presenting lessons of virtue and resilience in the face of adversity for mature readers as well.[3] Some of his most famous fairy tales include "The Emperor's New Clothes", "The Little Mermaid", "The Nightingale", "The Snow Queen", "The Ugly Duckling", "The Little Match Girl", "Thumbelina", and many others. His stories have inspired ballets, plays, and animated and live-action films.[4] One of Copenhagen's widest and busiest boulevards is named "H.C. Andersens Boulevard".[5]

Early life

Hans Christian Andersen was born in Odense, Denmark on 2 April 1805. He was an only child. Andersen's father, also Hans, considered himself related to nobility (his paternal grandmother had told his father that their family had belonged to a higher social class,[6] but investigations have disproved these stories).[6][7] A persistent speculation suggests that Andersen was an illegitimate son of King Christian VIII, but this notion has been challenged.[6]

Andersen's father, who had received an elementary school education, introduced Andersen to literature, reading to him Arabian Nights.[8] Andersen's mother, Anne Marie Andersdatter, was an illiterate washerwoman. Following her husband's death in 1816, she remarried in 1818.[8] Andersen was sent to a local school for poor children where he received a basic education and had to support himself, working as an apprentice to a weaver and, later, to a tailor. At fourteen, he moved to Copenhagen to seek employment as an actor. Having an excellent soprano voice, he was accepted into the Royal Danish Theatre, but his voice soon changed. A colleague at the theatre told him that he considered Andersen a poet. Taking the suggestion seriously, Andersen began to focus on writing.

Jonas Collin, director of the Royal Danish Theatre, held great affection for Andersen and sent him to a grammar school in Slagelse, persuading King Frederick VI to pay part of the youth's education.[9] Andersen had by then published his first story, "The Ghost at Palnatoke's Grave" (1822). Though not a stellar pupil, he also attended school at Elsinore until 1827.[10]

He later said his years in school were the darkest and most bitter of his life. At one school, he lived at his schoolmaster's home, where he was abused, being told that it was "to improve his character". He later said the faculty had discouraged him from writing, driving him into a depression.[11]

Career

Early work

A very early fairy tale by Andersen, "The Tallow Candle" (Danish: Tællelyset), was discovered in a Danish archive in October 2012. The story, written in the 1820s, was about a candle that did not feel appreciated. It was written while Andersen was still in school and dedicated to a benefactor in whose family's possession it remained until it turned up among other family papers in a local archive.[12]

In 1829, Andersen enjoyed considerable success with the short story "A Journey on Foot from Holmen's Canal to the East Point of Amager". Its protagonist meets characters ranging from Saint Peter to a talking cat. Andersen followed this success with a theatrical piece, Love on St. Nicholas Church Tower, and a short volume of poems. Although he made little progress writing and publishing immediately thereafter, in 1833 he received a small travel grant from the king, thus enabling him to set out on the first of many journeys through Europe. At Jura, near Le Locle, Switzerland, Andersen wrote the story "Agnete and the Merman". He spent an evening in the Italian seaside village of Sestri Levante the same year, inspiring the title of "The Bay of Fables".[13] In October 1834, he arrived in Rome. Andersen's travels in Italy were to be reflected in his first novel, a fictionalized autobiography titled The Improvisatore (Improvisatoren), published in 1835 to instant acclaim.[14][15]

Fairy tales and poetry

Andersen's initial attempts at writing fairy tales were revisions of stories that he heard as a child. Initially his original fairy tales were not met with recognition, due partly to the difficulty of translating them. In 1835, Andersen published the first two installments of his Fairy Tales (Danish: Eventyr; lit. "fantastic tales"). More stories, completing the first volume, were published in 1837. The collection comprises nine tales, including "The Tinderbox", "The Princess and the Pea", "Thumbelina", "The Little Mermaid" and "The Emperor's New Clothes". The quality of these stories was not immediately recognized, and they sold poorly. At the same time, Andersen enjoyed more success with two novels, O.T. (1836) and Only a Fiddler (1837);[16] the latter work was reviewed by a young Søren Kierkegaard. Much of his work was influenced by the Bible as when he was growing up Christianity was very important in the Danish culture.[17]

After a visit to Sweden in 1837, Andersen became inspired by Scandinavism and committed himself to writing a poem that would convey the relatedness of Swedes, Danes and Norwegians.[18] In July 1839, during a visit to the island of Funen, Andersen wrote the text of his poem Jeg er en Skandinav ("I am a Scandinavian")[18] to capture "the beauty of the Nordic spirit, the way the three sister nations have gradually grown together" as part of a Scandinavian national anthem.[18] Composer Otto Lindblad set the poem to music, and the composition was published in January 1840. Its popularity peaked in 1845, after which it was seldom sung.[18]

Andersen returned to the fairy tale genre in 1838 with another collection, Fairy Tales Told for Children. New Collection. First Booklet (Eventyr, fortalte for Børn. Ny Samling), which consists of "The Daisy", "The Steadfast Tin Soldier", and "The Wild Swans". He went on to publish "New Fairy Tales (1844). First Volume. First Collection", which contained "The Nightingale" and "The Ugly Duckling". After that came "New Fairy Tales (1845). First Volume. Second Collection" in which was found "The Snow Queen". "The Little Match Girl" appeared in December 1845 in the "Dansk Folkekalender (1846)" and also in "New Fairy Tales (1848). Second Volume. Second Collection".

1845 saw a breakthrough for Andersen with the publication of four translations of his fairy tales. "The Little Mermaid" appeared in the periodical Bentley's Miscellany, followed by a second volume, Wonderful Stories for Children. Two other volumes enthusiastically received were A Danish Story Book and Danish Fairy Tales and Legends. A review that appeared in the London journal The Athenæum (February 1846) said of Wonderful Stories, "This is a book full of life and fancy; a book for grandfathers no less than grandchildren, not a word of which will be skipped by those who have it once in hand."[3]

Andersen would continue to write fairy tales and published them in installments until 1872.[19]

Travelogues

In 1851, he published to wide acclaim In Sweden, a volume of travel sketches. A keen traveller, Andersen published several other long travelogues: Shadow Pictures of a Journey to the Harz, Swiss Saxony, etc. etc. in the Summer of 1831, A Poet's Bazaar, In Spain and A Visit to Portugal in 1866. (The last describes his visit with his Portuguese friends Jorge and Jose O'Neill, who were his fellows in the mid-1820s while living in Copenhagen.) In his travelogues, Andersen took heed of some of the contemporary conventions about travel writing, but always developed the genre to suit his own purposes. Each of his travelogues combines documentary and descriptive accounts of the sights he saw with more philosophical passages on topics such as being an author, immortality, and the nature of fiction in the literary travel report. Some of the travelogues, such as In Sweden, even contain fairy-tales.

In the 1840s, Andersen's attention returned to the stage, but with little success. He had better fortune with the publication of the Picture-Book without Pictures (1840). A second series of fairy tales began in 1838 and a third in 1845. Andersen was now celebrated throughout Europe, although his native Denmark still showed some resistance to his pretensions.

Between 1845 and 1864, H. C. Andersen lived at 67 Nyhavn, Copenhagen, where a memorial plaque now stands.[20]

Personal life

Meetings with Dickens

In June 1847, Andersen paid his first visit to England and enjoyed a triumphal social success during the summer. The Countess of Blessington invited him to her parties where intellectual people could meet, and it was at one such party that he met Charles Dickens for the first time. They shook hands and walked to the veranda, about which Andersen wrote in his diary: "We had come to the veranda, I was so happy to see and speak to England's now living writer, whom I love the most."[21]

The two authors respected each other's work and shared something important in common as writers: depictions of the poor and the underclass, who often had difficult lives affected both by the Industrial Revolution and by abject poverty. In the Victorian era there was a growing sympathy for children and an idealisation of the innocence of childhood.

Ten years later, Andersen visited England again, primarily to meet Dickens. He extended a brief visit to Dickens' home at Gads Hill Place into a five-week stay, to the distress of Dickens' family. After Andersen was told to leave, Dickens gradually stopped all correspondence between them, to the great disappointment and confusion of Andersen, who had quite enjoyed the visit and never understood why his letters went unanswered.[21]

Love life

In Andersen's early life, his private journal records his refusal to have sexual relations.[22][23]

Andersen often fell in love with unattainable women, and many of his stories are interpreted as references.[24] At one point, he wrote in his diary: "Almighty God, thee only have I; thou steerest my fate, I must give myself up to thee! Give me a livelihood! Give me a bride! My blood wants love, as my heart does!"[25] A girl named Riborg Voigt was the unrequited love of Andersen's youth. A small pouch containing a long letter from Voigt was found on Andersen's chest when he died, several decades after he first fell in love with her, and after he supposedly fell in love with others. Other disappointments in love included Sophie Ørsted, the daughter of the physicist Hans Christian Ørsted and Louise Collin, the youngest daughter of his benefactor Jonas Collin. One of his stories, "The Nightingale", was written as an expression of his passion for Jenny Lind and became the inspiration for her nickname, the "Swedish Nightingale".[26] Andersen was often shy around women and had extreme difficulty in proposing to Lind. When Lind was boarding a train to go to an opera concert, Andersen gave Lind a letter of proposal. Her feelings towards him were not the same; she saw him as a brother, writing to him in 1844: "farewell ... God bless and protect my brother is the sincere wish of his affectionate sister, Jenny".[27]

Andersen certainly experienced same-sex love as well: he wrote to Edvard Collin:[28] "I languish for you as for a pretty Calabrian wench ... my sentiments for you are those of a woman. The femininity of my nature and our friendship must remain a mystery."[29] Collin, who preferred women, wrote in his own memoir: "I found myself unable to respond to this love, and this caused the author much suffering." Likewise, the infatuations of the author for the Danish dancer Harald Scharff[30] and Carl Alexander, the young hereditary duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach,[31] did not result in any relationships.

According to Anne Klara Bom and Anya Aarenstrup from the H. C. Andersen Centre of University of Southern Denmark, "To conclude, it is correct to point to the very ambivalent (and also very traumatic) elements in Andersen's emotional life concerning the sexual sphere, but it is decidedly just as wrong to describe him as homosexual and maintain that he had physical relationships with men. He did not. Indeed that would have been entirely contrary to his moral and religious ideas, aspects that are quite outside the field of vision of Wullschlager and her like."[32] Many instead believe that rather than being heterosexual or homosexual, Andersen was bisexual, having romantic feelings for both sexes but most likely remaining celibate his whole life.

Death

In the spring of 1872, Andersen fell out of his bed and was severely hurt; he never fully recovered from the resultant injuries. Soon afterward, he started to show signs of liver cancer.[33]

He died on 4 August 1875, in a house called Rolighed (literally: calmness), near Copenhagen, the home of his close friends, the banker Moritz Melchior and his wife.[33] Shortly before his death, Andersen had consulted a composer about the music for his funeral, saying: "Most of the people who will walk after me will be children, so make the beat keep time with little steps."[33] His body was interred in the Assistens Kirkegård in the Nørrebro area of Copenhagen, in the family plot of the Collins. However in 1914 the stone was moved to another cemetery (today known as "Frederiksbergs ældre kirkegaard"), where younger Collin family members were buried. For a period, his, Edvard Collin's and Henriette Collin's graves were unmarked. A second stone has been erected, marking H.C. Andersen's grave, now without any mention of the Collin couple, but all three still share the same plot.[34]

At the time of his death, Andersen was internationally revered, and the Danish Government paid him an annual stipend as a "national treasure".[35]

Legacy and cultural influence

Archives, collections and museums

- The Hans Christian Andersen Museum in Solvang, California, a city founded by Danes, is devoted to presenting the author's life and works. Displays include models of Andersen's childhood home and of "The Princess and the Pea". The museum also contains hundreds of volumes of Andersen's works, including many illustrated first editions and correspondence with Danish composer Asger Hamerik.[36]

- The Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division was bequeathed an extensive collection of Andersen materials by the Danish-American actor Jean Hersholt.[37] Of particular note is an original scrapbook Andersen prepared for the young Jonas Drewsen.[38]

Art, entertainment and media

Films

- La petite marchande d'allumettes (1928; in English: The Little Match Girl), film by Jean Renoir[39] based on "The Little Match Girl"

- The Ugly Duckling (1931), an animated short film produced by Walt Disney Feature Animation, based on The Ugly Duckling.

- Andersen was played by Joachim Gottschalk in the German film The Swedish Nightingale (1941), which portrays his relationship with the singer Jenny Lind.

- The Red Shoes (1948) British drama film written, directed, and produced by the team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger based on The Red Shoes

- Hans Christian Andersen (1952), an American musical film starring Danny Kaye that, though inspired by Andersen's life and literary legacy, was meant to be neither historically nor biographically accurate; it begins by saying, "This is not the story of his life, but a fairy tale about this great spinner of fairy tales"

- Carevo novo ruho (The emperor's new clothes), a 1961 Croatian film, directed by Ante Babaja [40].

- The Rankin/Bass Productions-produced fantasy film, The Daydreamer (1966), depicts the young Hans Christian Andersen imaginatively conceiving the stories he would later write.

- The World of Hans Christian Andersen (1968), a Japanese anime fantasy film from Toei Doga, based on the works of Danish author Hans Christian Andersen

- The Little Mermaid (1989), an animated film based on The Little Mermaid created and produced at Walt Disney Feature Animation in Burbank, CA

- Thumbelina (1994), an animated film based on the "Thumbelina" created and produced at Sullivan Bluth Studios Dublin, Ireland

- Hans Christian Andersen: My Life as a Fairy Tale (2003), a British made-for-television film directed by Philip Saville, a fictionalised account of Andersen's early successes, with his fairy stories intertwined with events in his own life.[41]

- One Fantasia 2000 segment is based on The Steadfast Tin Soldier.

- Frozen (2013), an animated film produced by Walt Disney Animation Studios, was initially intended to be based on The Snow Queen, though numerous changes were made until the end result bore almost no resemblance to the original story.

Literature

Andersen's stories laid the groundwork for other children's classics, such as The Wind in the Willows (1908) by Kenneth Grahame and Winnie-the-Pooh (1926) by A. A. Milne. The technique of making inanimate objects, such as toys, come to life ("Little Ida's Flowers") would later also be used by Lewis Carroll and Beatrix Potter.

- "Match Girl", a short story by Anne Bishop (published in Ruby Slippers, Golden Tears)[42]

- "The Chrysanthemum Robe", a short story by Kara Dalkey (based on "The Emperor's New Clothes" and published in The Armless Maiden)

- The Nightingale by Kara Dalkey, lyrical adult fantasy novel set in the courts of old Japan

- The Girl Who Trod on a Loaf by Kathryn Davis, a contemporary novel about fairy tales and opera

- "Sparks", a short story by Gregory Frost (based on "The Tinder Box", published in Black Swan, White Raven)[43]

- "The Pangs of Love", a short story by Jane Gardam (based on "The Little Mermaid", published in Close Company: Stories of Mothers and Daughters)[44]

- "The Last Poems About the Snow Queen", a poem cycle by Sandra Gilbert (published in Blood Pressure).[45]

- The Snow Queen by Eileen Kernaghan, a gentle Young Adult fantasy novel that brings out the tale's subtle pagan and shamanic elements[46]

- The Wild Swans by Peg Kerr, a novel that brings Andersen's fairy tale to colonial and modern America [47]

- "Steadfast", a short story by Nancy Kress (based on "The Steadfast Tin Soldier", published in Black Swan, White Raven)[48]

- "In the Witch's Garden" (October 2002), a short story by Naomi Kritzer (based on "The Snow Queen", published in Realms of Fantasy magazine)

- Daughter of the Forest by Juliet Marillier, a romantic fantasy novel, set in early Ireland (thematically linked to "The Wild Swans")

- "The Snow Queen", a short story by Patricia A. McKillip (published in Snow White, Blood Red)

- "You, Little Match Girl", a short story by Joyce Carol Oates (published in Black Heart, Ivory Bones)

- "The Real Princess", a short story by Susan Palwick (based on "The Princess and the Pea", published in Ruby Slippers, Golden Tears)[49]

- "The Naked King" ("Голый Король (Goliy Korol)" 1937), "The Shadow" ("Тень (Ten)" 1940), and "The Snow Queen" ("Снежная Королева (Sniezhenaya Koroleva)" 1948) by Eugene Schwartz, reworked and adapted to the contemporary reality plays by one of Russia's playwrights. Schwartz's versions of The Shadow and The Snow Queen were later made into movies (1971 and 1967, respectively).[50][51]

- "The Sea Hag", a short story by Melissa Lee Shaw (based on "The Little Mermaid", published in Silver Birch, Blood Moon)[52]

- The Snow Queen by Joan D. Vinge, an award-winning novel that reworks "The Snow Queen"'s themes into epic science fiction[53]

- "The Steadfast Tin Soldier", a short story by Joan D. Vinge (published in Women of Wonder)

- "Swim Thru Fire", a comic by Sophia Foster-Dimino and Annie Mok, based partially off of "The Little Mermaid".

Mobile app

- GivingTales – the storytelling app for children was created in aid of UNICEF in 2015. Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tales are read by Roger Moore, Stephen Fry, Ewan McGregor, Joan Collins and Joanna Lumley.[54]

Monuments and sculptures

- Hans Christian Andersen (1880), even before his death, steps had already been taken to erect, in Andersen's honour, a large statue by sculptor August Saabye, which can now be seen in the Rosenborg Castle Gardens in Copenhagen.[4]

- Hans Christian Andersen (1896) by the Danish sculptor Johannes Gelert, at Lincoln Park in Chicago, on Stockton Drive near Webster Avenue[55]

- Hans Christian Andersen (1956), a statue by sculptor Georg J. Lober and designer Otto Frederick Langman, at Central Park Lake in New York City, opposite East 74th Street (40.7744306°N, 73.9677972°W)

Music

- Hans Christian Andersen (album), a 1994 album by Franciscus Henri

- The Song is a Fairytale (Sangen er et Eventyr), a song cycle based on fairy tales by Hans Christian Andersen, composed by Frederik Magle

Stage productions

- Sam the Lovesick Snowman at the Center for Puppetry Arts: a contemporary puppet show by Jon Ludwig inspired by The Snow Man.[56]

- Striking Twelve, a modern musical take on "The Little Match Girl", created and performed by GrooveLily.[57]

- The musical comedy Once Upon a Mattress is based on Andersen' work 'The Princess and the Pea'.

Television

- The Little Match Girl (1974) starring Lynsey Baxter

- Hans Christian Andersen: My Life as a Fairytale (2001), a semi-biographical television miniseries that fictionalises the young life of Danish author Hans Christian Andersen and includes fairy tales as short interludes, intertwined into the events of the young author's life

- In the "Metal Fish" episode of the Disney TV series The Little Mermaid, Andersen is a vital character whose inspiration for writing his tale is shown to have been granted by an encounter with the show's protagonists.

- The Fairytaler, a 2004 Danish animated television series based on the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen.

- Young Andersen, a 2005 biographical television miniseries that tells of the formative boarding school years of fairy tale writer.

Webseries

- Classic Alice (2014), a YouTube webseries, had a five-episode arc based on "The Butterfly"

Awards

- Hans Christian Andersen Awards, prizes awarded annually by the International Board on Books for Young People to an author and illustrator whose complete works have made lasting contributions to children's literature.[58]

- Hans Christian Andersen Literature Award, a Danish literary award established in 2010

Events and holidays

- Andersen's birthday, 2 April, is celebrated as International Children's Book Day.[59]

- The year 2005, designated "Andersen Year" in Denmark,[60] was the bicentenary of Andersen's birth, and his life and work was celebrated around the world.

- In Denmark, a well-attended "once in a lifetime" show was staged in Copenhagen's Parken Stadium during "Andersen Year" to celebrate the writer and his stories.[60]

- The annual H.C. Andersen Marathon, established in 2000, is held in Odense, Denmark

Places named after Andersen

- Hans Christian Andersen Airport, small airport servicing the Danish city of Odense

- Instituto Hans Christian Andersen, Chilean high school located in San Fernando, Colchagua Province, Chile

- Hans Christian Andersen Park, Solvang Ca

Postage stamps

- Andersen's legacy includes the postage stamps of Denmark and of Kazakhstan depicted above, depicting Andersen's profile.

Theme parks

- In Japan, the city of Funabashi has a children's theme park named after Andersen.[61] Funabashi is a sister city to Odense, the city of Andersen's birth.

- In China, a US$32 million theme park based on Andersen's tales and life was expected to open in Shanghai's Yangpu District in 2017.[62] Construction on the project began in 2005.[63]

Cultural references

In Gilbert and Sullivan's Savoy Opera Iolanthe, the Lord Chancellor mocks the Fairy Queen with a reference to Andersen, thereby implying that her claims are fictional:[64]

It seems that she's a fairy

From Andersen's library,

And I took her for

The proprietor

Of a Ladies' Seminary!

Selected works

Andersen's fairy tales include:

- The Angel (1843)

- The Bell

- The Emperor's New Clothes (1837)

- The Fir-Tree (1844)

- The Galoshes of Fortune (1838)

- The Happy Family

- The Ice-Maiden (1863)

- It's Quite True!

- Later Tales, published during 1867 & 1868 (1869)

- The Little Match Girl (1845)

- The Little Mermaid (1837)

- Little Tuck

- The Most Incredible Thing (1870)

- The Nightingale (1843)

- The Old House

- The Philosopher's Stone (1859)

- The Princess and the Pea (1835)

- The Red Shoes (1845)

- Sandman (1841)

- The Shadow (1847)

- The Shepherdess and the Chimney Sweep (1845)

- The Snow Queen (1844)

- The Steadfast Tin Soldier (1838)

- The Story of a Mother (1847)

- The Swineherd (1841)

- Thumbelina (1835)

- The Tinderbox (1835)

- The Ugly Duckling (1843)

- The Wild Swans (1838)

See also

- Kjøbenhavnsposten, a Danish newspaper in which Andersen published one of his first poems

- Pleated Christmas hearts, invented by Andersen

- Vilhelm Pedersen, the first illustrator of Andersen's fairy tales

- Collastoma anderseni sp. nov. (Rhabdocoela: Umagillidae: Collastominae), an endosymbiont from the intestine of the sipunculan Themiste lageniformis, for a species named after Andersen.

References

- ↑ "Centrets vision og mission - H.C. Andersen Centret". andersen.sdu.dk.

- ↑ Wenande, Christian (13 December 2012). "Unknown Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale discovered". The Copenhagen Post. Archived from the original on 14 December 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- 1 2 Wullschläger 2002

- 1 2 Bredsdorff 1975

- ↑ Google Maps, by City Hall Square (Rådhuspladsen), continues eastbound as the bridge "Langebro"

- 1 2 3 Rossel 1996, p. 6

- ↑ Askgaard, Ejnar Stig. "The Lineage of Hans Christian Andersen". Odense City Museums. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012.

- 1 2 Rossel 1996, p. 7

- ↑ Hans Christian Andersen - Childhood and Education. Danishnet.

- ↑ "H.C. Andersens skolegang i Helsingør Latinskole". Hcandersen-homepage.dk. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ Wullschläger 2002, p. 56.

- ↑ "Local historian finds Hans Christian Andersen's first fairy tale". Politiken.dk. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ↑ "Andersen Festival, Sestri Levante". Andersen Festival. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ↑ Christopher John Murray (13 May 2013). Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760-1850. Routledge. p. 20. ISBN 1-135-45579-1.

- ↑ Jan Sjåvik (19 April 2006). Historical Dictionary of Scandinavian Literature and Theater. Scarecrow Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8108-6501-3.

- ↑ Only a Fiddler from Archive.org

- ↑ FutureLearn. "Biblical themes in Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tales - Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales - Hans Christian Andersen Centre". FutureLearn. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ↑ "Who Was Hans Christian Andersen?". Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- ↑ "Official Tourism Site of Copenhagen". Visitcopenhagen.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2008. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- 1 2 "H.C. Andersen og Charles Dickens 1857". Hcandersen-homepage.dk. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ↑ Lepage, Robert (18 January 2006). "Bedtime stories". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 July 2006.

- ↑ Recorded using "special Greek symbols".Garfield, Patricia (21 June 2004). "The Dreams of Hans Christian Andersen" (PDF). p. 29. Retrieved 20 July 2006.

- ↑ Hastings, Waller (4 April 2003). "Hans Christian Andersen". Northern State University. Archived from the original on 23 November 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ↑ "The Tales of Hans Christian Andersen". Scandinavian.wisc.edu. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ "H.C. Andersen og Jenny Lind". 2 July 2014.

- ↑ "H.C. Andersen homepage (Danish)". Hcandersen-homepage.dk. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ Hans Christian Andersen's correspondence, ed Frederick Crawford6, London. 1891.

- ↑ Seriality and Texts for Young People: The Compulsion to Repeat edited by M. Reimer, N. Ali, D. England, M. Dennis Unrau, Melanie Dennis Unrau

- ↑ de Mylius, Johan. "The Life of Hans Christian Andersen. Day By Day". Hans Christian Andersen Center. Retrieved 22 July 2006.

- ↑ Pritchard, Claudia (27 March 2005). "His dark materials". The Independent. Archived from the original on 14 March 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2006.

- ↑ Hans Christian Andersen Center, Hans Christian Andersen – FAQ

- 1 2 3 Bryant, Mark: Private Lives, 2001, p. 12.

- ↑ in Danish, http://www.hcandersen-homepage.dk/?page_id=6226

- ↑ "Hans Christian Andersen".

- ↑ "The Hans Christian Andersen Museum". SolvangCA.com. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ↑ "Jean Hersholt Collections". Loc.gov. 15 April 2009. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ "Billedbog til Jonas Drewsen". (15 April 2009) Retrieved 2 November 2009.

- ↑ La petite marchande d'allumettes (1928) on IMDb

- ↑ https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0193044/

- ↑ "See IMDb film database".

- ↑ Ellen Datlow; Terri Windling (30 September 2014). Ruby Slippers, Golden Tears. Open Road Media Sci-Fi & Fantasy. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-4976-6858-4.

- ↑ Altmann, Anna E.; De Vos, Gail (2001). Tales, Then and Now: More Folktales as Literary Fictions for Young Adults. Libraries Unlimited. p. 261. ISBN 9781563088315.

- ↑ Maunder, Andrew (2007). The Facts on File Companion to the British Short Story. New York: Facts on File. p. 163. ISBN 081605990X.

...The pangs of love ... is a self-consciously feminist reworking of Hans Christian Anderson's [sic] story of 'The Little Mermaid'...

- ↑ Clark, Kevin (1992). "Learning to Read the Mother Tongue: On Sandra Gilbert's "Blood Pressure"". University of Iowa.

- ↑ "Anchors Landing. A residential community in Granite Falls, North Carolina". www.anchorslandinghoa.org.

- ↑ Bear, Bethany Joy (2009). Fairy Tales Reimagined: Essays on New Retellings. McFarland. pp. 44–57. ISBN 978-0-7864-4115-0.

- ↑ "Nancy Kress Bibliography". Nancy Kress. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ↑ The Sum of a Life. "Stories and Movement". Bernie Gourley. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ↑ "Snezhnaya koroleva (The Snow Queen)". imdb.com. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ↑ "Ten (The Shadow)". imdb.com. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ↑ Webmaster, Rodger Turner,. "The SF Site Featured Review: Silver Birch, Blood Moon". www.sfsite.com. Retrieved 2018-01-18.

- ↑ "The Snow Queen | Joan D. Vinge | Macmillan". US Macmillan. Retrieved 2018-01-18.

- ↑ "GivingTales". 18 June 2015 – via IMDb.

- ↑ "The Hans Christian Andersen Statue". Skandinaven. 17 September 1896.

- ↑ "Jon Ludwig's ''Sam the Lovesick Snowman''". Puppet.org. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ "Striking 12". GrooveLily. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ↑ "Hans Christian Andersen Awards". International Board on Books for Young People.

- ↑ "International Children's Book Day". International Board on Books for Young People. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

Since 1967, on or around Hans Christian Andersen's birthday, 2 April, International Children's Book Day (ICBD) is celebrated to inspire a love of reading and to call attention to children's books.

- 1 2 Brabant, Malcolm (1 April 2005). "Enduring legacy of author Andersen". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ↑ "H.C. Andersen Park - Funabashi". City of Funabashi Tourism. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- ↑ Fan, Yanping (2016-11-11). "安徒生童话乐园明年开园设七大主题区" [Andersen fairy tales opening next year to set up seven theme areas]. Sina Corp. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- ↑ Zhu, Shenshen (2013-07-16). "Fairy-tale park takes shape in city". Shanghai Daily. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- ↑ "W.S.Gilbert - Iolanthe, ACT I".

Bibliography

- Andersen, Hans Christian (2005) [2004]. Jackie Wullschläger, ed. Fairy Tales. Tiina Nunnally. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-670-03377-4.

- Andersen, Jens (2005) [2003]. Hans Christian Andersen: A New Life. Tiina Nunnally. New York, Woodstock, and London: Overlook Duckworth. ISBN 978-1-58567-737-5.

- Binding, Paul (2014). Hans Christian Andersen : European witness. Yale University Press.

- Bredsdorff, Elias (1975). Hans Christian Andersen: the story of his life and work 1805–75. Phaidon. ISBN 0-7148-1636-1. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- Stig Dalager, Journey in Blue, historical, biographical novel about H.C.Andersen, Peter Owen, London 2006, McArthur & Co., Toronto 2006.

- Roes, André, Kierkegaard en Andersen, Uitgeverij Aspekt, Soesterberg (2017) ISBN 9789463382151

- Ruth Manning-Sanders, Swan of Denmark: The Story of Hans Christian Andersen, Heinemann, 1949

- Rossel, Sven Hakon (1996). Hans Christian Andersen: Danish Writer and Citizen of the World. Rodopi. ISBN 90-5183-944-8.

- Stirling, Monica (1965). The Wild Swan: The Life and Times of Hans Christian Andersen. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc.

- Terry, Walter (1979). The King's Ballet Master. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. ISBN 0-396-07722-6.

- Wullschläger, Jackie (2002) [2000]. Hans Christian Andersen: The Life of a Storyteller. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-91747-9.

- Zipes, Jack (2005). Hans Christian Andersen: The Misunderstood Storyteller. New York and London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-97433-X.

External links

- Hans Christian Andersen at Encyclopædia Britannica

- Works by Hans Christian Andersen at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Hans Christian Andersen at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Hans Christian Andersen at Internet Archive

- Works by Hans Christian Andersen at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Hans Christian Andersen at Open Library

- The Story of My Life (1871) by Hans Christian Andersen - English

- Hans Christian Andersen Information Odense

- Hans Christian Andersen biography

- Andersen Fairy Tales

- And the cobbler's son became a princely author Details of Andersen's life and the celebrations.

- The Hans Christian Andersen Centre - contains many Andersen's stories in Danish and English

- The Hans Christian Andersen Museum in Odense has a large digital collection of Hans Christian Andersen papercuts, drawings and portraits - You can follow his travels across Europe and explore his Nyhavn study.

- The Orders and Medals Society of Denmark has descriptions of Hans Christian Andersen's Medals and Decorations.

- Jean Hersholt Collections of Hans Christian Andersen From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

- Hans Christian Andersen on IMDb