Fort Smith, Northwest Territories

| Fort Smith Thebacha | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

Fort Smith  Fort Smith | |

| Coordinates: 60°00′19″N 111°53′26″W / 60.00528°N 111.89056°WCoordinates: 60°00′19″N 111°53′26″W / 60.00528°N 111.89056°W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Territory | Northwest Territories |

| Region | South Slave Region |

| Constituency | Thebacha |

| Census division | Region 5 |

| Town | 1 October 1966[1] |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Lynn Napier-Buckley |

| • Senior administrative officer | Keith Morrison |

| • MLA | Louis Sebert |

| Area(2016)[2] | |

| • Land | 92.79 km2 (35.83 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 205 m (673 ft) |

| Population (2016)[2] | |

| • Total | 2,542 |

| • Density | 27.4/km2 (71/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC−7 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−6 (MDT) |

| Postal code | X0E 0P0 |

| Area code(s) | 867 |

| Telephone Exchange | 872 621 870 |

| GNBC Code | LAILN |

| - Living cost | 132.5A |

| - Food price index | 117.8B |

| Climate | Dfc |

| NTS Map | 075D04 |

| Website |

fortsmith |

|

Sources: Department of Municipal and Community Affairs,[3] Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre,[4] Canada Flight Supplement[5] ^A 2013 figure based on Edmonton = 100[6] ^B 2015 figure based on Yellowknife = 100[6] | |

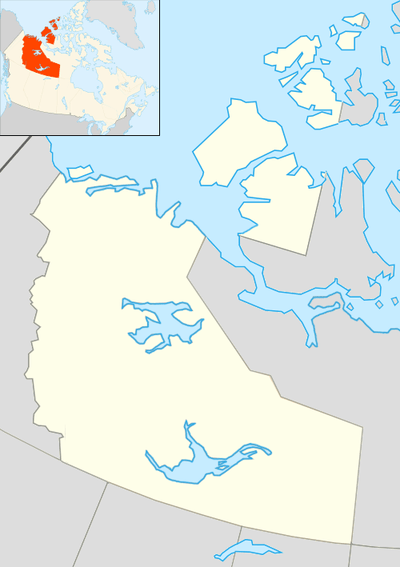

Fort Smith (Chipewyan: Thebacha "beside the rapids") is a town in the South Slave Region of the Northwest Territories (NWT), Canada. It is located in the southeastern portion of the Northwest Territories, on the Slave River and adjacent to the Northwest Territories/Alberta border.

History

Fort Smith was founded around the Slave River. It served a vital link for water transportation between southern Canada and the western Arctic. Early fur traders found an established portage route from what is now Fort Fitzgerald on the western bank of the Slave River to Fort Smith. This route allowed its users to navigate the four sets of impassable rapids (Cassette Rapids, Pelican Rapids, Mountain Rapids, and Rapids of the Drowned). The portage trail had been traditionally used by local Indigenous people for centuries.[7]

The Indigenous population of the region shifted as the fortunes of the tribes changed. By 1870, Cree had occupied the Slave River Valley. The Slavey had moved north by this time and the Chipewyan had also begun moving into the area.

Peter Pond of the North West Company was the first white trader to travel on the Slave River and make contact with Indigenous people in this region. He established a post on Lake Athabasca called Fort Chipewyan in the 1780s, at the head of the Slave River.

The fur trade, dominated by the activities of the Hudson's Bay Company, penetrated deeper into the Mackenzie River district in the 19th century. York boats were used to run the Slave River rapids and where needed small portages were established to bypass the most dangerous areas. Nonetheless, serious mishaps were bound to happen, and the section of the Slave River became known as 'The Rapids of the Drowned'. In 1872, the Hudson's Bay Company built an outpost called Smith's Landing (Fort Fitzgerald) at the most southern set of the Slave River rapids. In 1874, another outpost was constructed at the most northern set of rapids. It was called Fort Smith. Both posts were named in honour of Donald Alexander Smith.

In 1876, the Roman Catholic Mission was moved from Salt River to Fort Smith while the community was prospering.[7]

In 1886, the Hudson's Bay Company launched the steam-propelled vessel SS Wrigley to run from Fort Smith to the Mackenzie River. The steamer SS Grahame ran the Slave River from Fort McMurray to the head of the rapids at Smith's Landing beginning in 1882.[8] In 1898, the Yukon Gold Rush brought many gold seekers over the portages and through Fort Smith. In 1908, a new HBC steamer paddlewheeler, SS Mackenzie River, was launched to operate on the Slave and Mackenzie Rivers below Fort Smith (see Boats of the Mackenzie River watershed).

In 1911, government was established in Fort Smith when Ottawa sent an Indian agent and a regional medical doctor, and the Royal Northwest Mounted Police opened a detachment. With these developments, Fort Smith became not only the transportation centre for the western Arctic but the administrative centre as well.

The mission sawmill produced lumber for the first hospital, St. Anne's, built in 1914 for the Grey Nuns. The sawmill also supplied the lumber for the first school built in 1915. Also maintained by the Roman Catholic Mission was St. Bruno's Farm that supplied produce, meat, and dairy products. Until it was closed in the 1920s, the farm supplied all the church's missions in the western Arctic. It maintained a herd of more than 140 cattle.[7]

Horse-drawn freight services were complemented by tractors in 1919, when the Alberta & Arctic Transportation Company, a subsidiary of Lamson & Hubbard Trading Company, commissioned two 75-horsepower (56 kW) tractors on the Slave River portage to haul commercial freight from one side of the rapids to the other.

With the discovery of oil at Norman Wells in 1920, a federal government administration building was constructed to house the new Northwest Territories branch and the first court of justice in the Mackenzie District. The Union Bank of Canada, making use of a tent, opened the first bank in the Northwest Territoies in Fort Smith in June 1921.[9][10]

SS Distributor was launched in 1920 by the Lamson & Hubbard Trading Company to service its trading posts along the Mackenzie River. This group was taken over by the HBC in 1924. By the 1930s, a significant part of the Fort Smith economy was centred around ship and barge building with the HBC and Northern Transportation Company Limited (NTCL) establishing shipyards below Fort Smith.

Wood Buffalo National Park was established in 1922 with its operations and administration headquarters in Fort Smith.

In 1925, Fort Smith received the first Royal Canadian Corps of Signals air radio station in the Northwest Territories. An airport was later built in 1928.

The discovery of gold in Yellowknife in 1938 also represented an economic boost to Fort Smith as many prospectors came passing through. In the same year, an Anglican Mission house was built and a church was added in 1939.

In 1942–1943, Fort Smith played its own small part in the war effort when huge armies raged across the globe in the Second World War. With a population of 250, Fort Smith hosted 2,000 US Army soldiers who were en route to the Canol Oil Pipeline Project at Norman Wells and the Canol Road. They brought hundreds of barge loads of supplies; and in order to move these, they built a tractor road from Fort Smith to Hay River and even farther north.

The continued gold fever that fuelled Yellowknife's growth also allowed Fort Smith's population to grow five-fold in the decade following 1945. This was reflected in the increase in government administrative facilities and the growth of its role as a transportation hub for the Mackenzie District.

Fort Smith was incorporated as a village in 1964; two years later, with a population of 2,130, the village became a town on October 1, 1966. The all-weather road to Hay River was officially completed in 1966 as well, permanently linking Fort Smith to the south.

The completion of a southern rail link to Hay River in 1964 meant that Fort Smith's role as the transportation hub was largely negated; and, subsequently, shipping operations on the Slave River ceased in 1968.

When Yellowknife became the territorial capital in 1967, Fort Smith still remained the administrative centre of the government of the Northwest Territories' vast region. See History of Northwest Territories capital cities.

On Friday August 9, 1968, disaster struck Fort Smith when a landslide some 3,300 by 990 ft (1,010 by 300 m) broke away from the riverbank causing property damage and killing one person. The riverbank area has since been sloped to stabilize it; and now the gentle hillside is known as the Riverbank Park, complete with groomed trails, picnic areas, and a viewing platform where one can see the Rapids of the Drowned.[11]

In 1970, the Adult Vocational Training Centre was opened. Its operations were later expanded and in 1981 it became Thebacha College. A few years later, Arctic College was created by the government of the Northwest Territories and the Thebacha Campus was also home to the headquarters offices. In 1995, the college changed its name to Aurora College to allow Nunavut the use of the Arctic College name.[12]

Today, Fort Smith's economy is based on the federal, territorial, and aboriginal governments along with education and tourism. In 2008, there was some interest in re-establishing a portage route to supply the Fort McMurray oilsands operations.

Geography

The town is approximately 300 km (190 mi) southeast of Yellowknife, the territorial capital. The park headquarters for Wood Buffalo National Park is located in Fort Smith. The headquarters and Thebacha Campus of Aurora College is located in Fort Smith; it is the largest of the three campus locations in the Northwest Territories. Fort Smith is located in the South Slave Region (administrative) and Region 5, Northwest Territories (census division). The town was previously in the Fort Smith Region census division.

Fort Smith is accessible all year long via the Fort Smith Highway. A winter road operates for several months to connect Fort Smith to Fort Chipewyan and from there to Fort McMurray. An all-weather road named Pine Lake Road links Fitzgerald.[13]

Climate

Fort Smith has a dry continental subarctic climate with very long winters combined with warm but relatively short summers.

The highest temperature ever recorded in Fort Smith was 39.4 °C (102.9 °F) on 18 July 1941.[14] The coldest temperature ever recorded was −57.2 °C (−71.0 °F) on 26 December 1917.[15] These are both the hottest and coldest temperatures ever recorded in the Northwest Territories.[16]

| Climate data for Fort Smith Airport, 1981−2010 normals, extremes 1913−present[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 8.4 | 11.6 | 13.9 | 29.6 | 32.7 | 38.9 | 41.7 | 38.5 | 31.3 | 25.9 | 12.1 | 8.9 | 41.7 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 8.7 (47.7) |

12.2 (54) |

15.0 (59) |

30.0 (86) |

31.8 (89.2) |

35.0 (95) |

39.4 (102.9) |

35.3 (95.5) |

31.7 (89.1) |

26.7 (80.1) |

13.3 (55.9) |

9.4 (48.9) |

39.4 (102.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −17.8 (0) |

−13.5 (7.7) |

−5.0 (23) |

6.0 (42.8) |

14.2 (57.6) |

20.9 (69.6) |

23.3 (73.9) |

20.8 (69.4) |

13.6 (56.5) |

4.2 (39.6) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−15.0 (5) |

3.7 (38.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −22.4 (−8.3) |

−19.1 (−2.4) |

−11.8 (10.8) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

7.8 (46) |

14.4 (57.9) |

17.0 (62.6) |

14.7 (58.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−11.4 (11.5) |

−19.3 (−2.7) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −27.0 (−16.6) |

−24.7 (−12.5) |

−18.5 (−1.3) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

1.3 (34.3) |

7.9 (46.2) |

10.7 (51.3) |

8.6 (47.5) |

3.1 (37.6) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

−15.1 (4.8) |

−23.5 (−10.3) |

−7.3 (18.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −53.3 (−63.9) |

−55.0 (−67) |

−48.3 (−54.9) |

−40.6 (−41.1) |

−23.0 (−9.4) |

−7.2 (19) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−6.1 (21) |

−15.0 (5) |

−31.1 (−24) |

−42.8 (−45) |

−57.2 (−71) |

−57.2 (−71) |

| Record low wind chill | −60.4 | −58.4 | −55.7 | −50.4 | −26.2 | −8.0 | 0.0 | −4.7 | −17.8 | −35.3 | −48.8 | −59.6 | −60.4 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 16.5 (0.65) |

12.2 (0.48) |

13.2 (0.52) |

12.7 (0.5) |

27.8 (1.094) |

48.8 (1.921) |

54.5 (2.146) |

54.5 (2.146) |

42.4 (1.669) |

32.4 (1.276) |

22.3 (0.878) |

16.6 (0.654) |

353.6 (13.921) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.1 (0.004) |

0.1 (0.004) |

0.3 (0.012) |

6.2 (0.244) |

22.6 (0.89) |

48.7 (1.917) |

54.5 (2.146) |

54.3 (2.138) |

41.6 (1.638) |

14.0 (0.551) |

1.5 (0.059) |

0.3 (0.012) |

244.3 (9.618) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 24.0 (9.45) |

18.7 (7.36) |

17.5 (6.89) |

7.8 (3.07) |

5.7 (2.24) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.2 (0.08) |

1.0 (0.39) |

21.5 (8.46) |

30.1 (11.85) |

23.8 (9.37) |

150.2 (59.13) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 10.8 | 8.6 | 7.9 | 5.8 | 8.5 | 10.9 | 11.8 | 12.6 | 12.1 | 13.7 | 13.5 | 11.6 | 127.7 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 2.8 | 7.4 | 10.9 | 11.8 | 12.6 | 11.7 | 7.5 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 66.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 12.3 | 10.1 | 8.6 | 3.7 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 8.4 | 14.7 | 13.3 | 73.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 1500 LST) | 79.8 | 77.6 | 67.1 | 51.4 | 42.3 | 43.8 | 48.2 | 52.8 | 58.0 | 71.4 | 83.8 | 82.0 | 63.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 61 | 117 | 167 | 240 | 282 | 316 | 296 | 268 | 133 | 86 | 45 | 27 | 2,038 |

| Source #1: Environment Canada[17][18][19] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Danish Meteorological Institute (sun, 1931–1960)[20] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

In the 2016 Census, Statistics Canada reported that the Town of Fort Smith had a population of 2,542 living in 957 of its 1088 total dwellings, an 1.8% change from its 2011 population of 2,496. With a land area of 92.79 km2 (35.83 sq mi), it had a population density of 27.395/km2 (70.953/sq mi) in 2016.[2]

According to the 2016 Census, the majority of people in Fort Smith (1,645) were Indigenous of which 920 were First Nations, 585 were Métis and 135 Inuit. The main languages are English, Chipewyan (Dene), Cree, Dogrib (Tłı̨chǫ), Slavey-Hare, Inuinnaqtun (Inuvialuktun) and Inuktitut. In 2017, the Government of the Northwest Territories estimated that the population was 2,562 compared to 2,506 in 2007, resulting in an average annual growth rate of 0.2% between 2007 and 2017.[6]

| Historical population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources: NWT Bureau of Statistics (2001 - 2017)[21] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Attractions

Fort Smith is the home of the Northern Life Museum and home of the museum ship Radium King.[22]

Every year the South Slave Friendship Festival, a music and arts festival, occurs in Fort Smith, usually in August. Musicians and artists from across the Northwest Territories and many other faraway places come to interact with other artists and show off their talents to the public.[22]

Many tourists come to see the world-class Slave River and many kayakers try its rapids.[22]

Fort Smith Mission Park is a popular tourist attraction featuring historic buildings and a grotto from the Oblate Catholic Mission.[22]

In the summer months, pelicans can be seen nesting on the various rapids near Fort Smith. Whooping cranes, an endangered species, also nest in the area during the summer and can be viewed via air charters as ground access is prohibited.[22]

Government

Local government consists of the Town of Fort Smith Council with 9 members (7 councillors, deputy mayor and mayor). The mayor works part-time and council is elected every three years.[23] As of 2018 the current mayor of Fort Smith is Lynn Napier-Buckley.[3]

Fort Smith is represented by the Salt River First Nation #195[24] and are part of the Akaitcho Territory Government.[25][26] As of June 2012 the Salt River First Nation had given the Akaitcho Territory Government the mandatory six months notice that they would be separating from the organization.[27]

The Northwest Territory Métis Nation is located in Fort Smith. In 1996, a framework agreement was signed with the government of the Northwest Territories and the government of Canada to commence negotiations on land, resources and self-government.[28]

Education

There are a number of educational facilities in Fort Smith including Joseph Burr Tyrrell Elementary School, Paul William Kaeser High School[29] and the Thebacha Campus of Aurora College.[12] Additionally, the main office of the South Slave Divisional Education Council is located in the town.[29]

Notable residents

Fort Smith is the birthplace of Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England and former governor of the Bank of Canada.[30]

See also

References

- ↑ "Town of Fort Smith News (Volume 22)" (PDF) (PDF). Town of Fort Smith. September 2011. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-01-13. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Census Profile, 2016 Census Fort Smith, Town (Census subdivision), Northwest Territories and Northwest Territories (Territory)

- 1 2 "NWT Communities - Fort Smith". Government of the Northwest Territories: Department of Municipal and Community Affairs. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ↑ "Northwest Territories Official Community Names and Pronunciation Guide". Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre. Yellowknife: Education, Culture and Employment, Government of the Northwest Territories. Archived from the original on 2016-01-13. Retrieved 2016-01-13.

- ↑ Canada Flight Supplement. Effective 0901Z 19 July 2018 to 0901Z 13 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Fort Smith - Statistical Profile (2006-2017)" (PDF). NWT Bureau of Statistics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-08-29.

- 1 2 3 Fort Smith (N.W.T.). Tourism Committee (1979). On the Banks of the Slave : a History of the Community of Fort Smith, Northwest Territories. Tourism Committee. Retrieved 2016-05-08.

- ↑ McCormack, Patricia Alice (2010). Fort Chipewyan and the Shaping of Canadian History, 1788-1920s. UBC Press. pp. 75, 80, 128, 141, 199, 286. ISBN 9780774816687.

The Hudson's Bay Company launched the Grahame at Fort Chipewyan in 1883 for service on the Athabasca, lower Peace, and upper Slave rivers. This ship could carry 140 tons.... It ran from Fort McMurray to Smith's Landing, up the Clearwater River to the Methye Portage, and up the Peace River to the Vermilion Chutes.

- ↑ As Long as this Land Shall Last: A History of Treaty 8 and Treaty 11, 1870-1939

- ↑ Union Bank of Canada, Fort Smith, North West Territories, 1921

- ↑ On the Banks of the Slave: A History of the Community of Fort Smith, Northwest Territories. Published by the Tourism Committee of Fort Smith, Department of Education Northwest Territories, 1979.

- 1 2 "Aurora College". Retrieved 2014-02-14.

- ↑ "Map of Wood Buffalo National Park". Parks Canada. Government of Canada. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ↑ "Daily Data Report for July 1941". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ↑ "Daily Data Report for December 1917". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ↑ Columbo, John Robert (1995), The 1996 Canadian Global Almanac, Toronto, Ontario: Macmillan Canada, p. 22

- ↑ "Fort Smith A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Climate ID: 2202200. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ↑ "Fort Smith". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ↑ "Fort Smith". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ↑ Cappelen, John; Jensen, Jens. "Canada - Fort Smith, Mackenzie District" (PDF). Climate Data for Selected Stations (1931-1960) (in Danish). Danish Meteorological Institute. p. 51. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 27, 2013. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ↑ Population Estimates By Community from the GNWT

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Town of Fort Smith (attractions)". Retrieved 2016-05-08.

- ↑ "Mayor and Council". Fortsmith.ca. Retrieved 2016-05-08.

- ↑ "Salt River First Nation". Srfn195.com. Retrieved 2016-05-08.

- ↑ "First Nation Profiles Akaitcho Territory Government". Wayback.archive.org. Archived from the original on 2014-07-13. Retrieved 2016-05-08.

- ↑ "Akaitcho Territory Government". Daair.gov.nt.ca. 2008-09-05. Retrieved 2016-05-08.

- ↑ "Salt River parting from Akaitcho First Nation". Cbc.ca. 2012-06-30. Retrieved 2016-05-08.

- ↑ "Northwest Territory Métis Nation". Nwtmetisnation.ca. Retrieved 2016-05-08.

- 1 2 "South Slave Divisional Education Council". Retrieved 2014-02-14.

- ↑ "UK Treasury Press Release". Hm-treasury.gov.uk. 2012-11-26. Retrieved 2016-05-08.

Notes

- ↑ Climate data was recorded at Fort Smith from July 1913 to May 1946 and at Fort Smith Airport from September 1943 to present.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort Smith, Northwest Territories. |

- Aurora College - Official School Website

- Pentecostal Sub-Arctic Leadership Training College - Official School Website

- Northern Journal - community newspaper

.jpg)