Women in Nigeria

| Gender Inequality Index | |

|---|---|

| Value | NR |

| Rank | NR |

| Maternal mortality (per 100,000) | 630 (2010) |

| Women in parliament | 6.7% (2012) |

| Females over 25 with secondary education | NA |

| Women in labour force | 47.9% (2011) |

| Global Gender Gap Index[1] | |

| Value | 0.6469 (2013) |

| Rank | 106th out of 144 |

Women's social role in Nigeria differs according to religious and geographic factors. Nationally, 27% of Nigerian women between the ages of 15 and 49 were victims of Female Genital Mutilation, as of 2012.[2] A large number of the children work as maids, shop helps and street hawkers. The use of young girls in economic activities exposes them to the dangers and other problems such as sexual assault, missing classes, lack of parental care and exploitation.[3]

Regional differences

Northern Nigeria

In the north, archaic practices were still common. This process meant, generally, less formal education; early teenage marriages, especially in rural areas; and confinement to the household, which was often polygynous, except for visits to family, ceremonies, and the workplace, if employment were available and permitted by a girl's family or husband. For the most part, Hausa women did not work in the fields, whereas Kanuri women did; both helped with harvesting and were responsible for all household food processing.

Urban women sold cooked foods, usually by sending young girls out onto the streets or operating small stands. Research indicated that this practice was one of the main reasons city women gave for opposing schooling for their daughters. Even in elite houses with educated wives, women's presence at social gatherings was either nonexistent or very restricted. In the modern sector, a few women were appearing at all levels in offices, banks, social services, nursing, radio, television, and the professions (teaching, engineering, environmental design, law, pharmacy, medicine, and even agriculture and veterinary medicine). This trend resulted from women's secondary schools, teachers' colleges, and in the 1980s women holding approximately one-fifth of university places—double the proportion of the 1970s. Research in the 1980s indicated that, for the Muslim north, education beyond primary school was restricted to the daughters of the business and professional elites, and in almost all cases, courses and professions were chosen by the family, not the woman themselves.

However, in the last few years, the rate of women's employment has apparently increased as more women have been employed in the modern sector. You find them as cashiers in the banks, teachers in public and private primary and secondary schools, nurses at hospitals as well as television hosts of different TV programs. Although, the issue of women not occupying top positions still remains a huge challenge all over the country and across all sectors as most of these positions are occupied by men with little opportunities for equally qualified women. In addition, young ladies deciding on courses and professions to choose from now have the full autonomy to do that in some households especially in the southern part of the country. However, the north still lags behind in these apparent changes due to cultural laws.

Southern Nigeria

In the south, women traditionally had economically important positions in interregional trade and the markets, worked on farms as major labor sources, and had influential positions in traditional systems of local organization. The south, like the north, had been polygynous; in 1990 it still was for many households, including those professing Christianity.

Women in the south, had received Western-style education since the nineteenth century, so they occupied positions in the professions and to some extent in politics. In addition, women headed households, something not seriously considered in Nigeria's development plans. Such households were more numerous in the south, but they were on the rise everywhere.

Recognition by authorities

Generally, in Nigeria, development planning refers to "adult males," "households," or "families". Women were included in such units but not as a separate category. Up until the 1980s, the term "farmer" was assumed to be exclusively male, even though in some areas of the south women did most of the farm work. In Nigerian terms, a woman was almost always defined as someone's daughter, wife, mother, or widow.

Single women were suspect, although they constituted a large category, especially in the cities, because of the high divorce rate. Traditionally, and to some extent this remained true in popular culture, single adult women were seen as available sexual partners should they try for some independence and as easy victims for economic exploitation. In Kaduna State, for example, investigations into illegal land expropriations noted that women's farms were confiscated almost unthinkingly by local chiefs wishing to sell to urban-based speculators and would-be commercial farmers.

Women's rights

Female genital mutilation

Female genital cutting (also known as female genital mutilation) in Nigeria accounts for the most female genital cutting/mutilation (FGM/C) cases worldwide.[4] The practice is considered harmful to girls and women and a violation of human rights.[5] FGM causes infertility, maternal death, infections, and the loss of sexual pleasure.[6]

Nationally, 27% of Nigerian women between the ages of 15 and 49 were victims of FGM, as of 2012.[2] In the last 30 years, prevalence of the practice has decreased by half in some parts of Nigeria.[5]

Girl child labour

A large number of the children work as maids, shop helps and street hawkers. The use of young girls in economic activities exposes them to the dangers and other problems such as sexual assault, missing classes, lack of parental care and exploitation.[7]

Polygamy

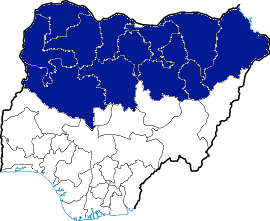

12 out of the 36 Nigerian states recognize polygamous marriages as being equivalent to monogamous marriages. All twelve states are governed by Islamic Sharia Law. The states, which are all northern, include the states of Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Niger, Sokoto, Yobe, and Zamfara [8] which allows for a man to take more than one wife.[9]

Women's advocacy

A national feminist movement was inaugurated in 1982, and a national conference held at Ahmadu Bello University. The papers presented there indicated a growing awareness by Nigeria's university-educated women that the place of women in society required a concerted effort and a place on the national agenda; the public perception, however, remained far behind.

For example, a feminist meeting in Ibadan came out against polygamy and then was soundly criticized by market women, who said they supported the practice because it allowed them to pursue their trading activities and have the household looked after at the same time. Research in the north indicated that many women opposed the practice, and tried to keep bearing children to stave off a second wife's entry into the household. Although women's status would undoubtedly rise, for the foreseeable future Nigerian women lacked the opportunities of men.

Notable figures

- Agbani Darego — Model and Beauty Queen

- Amina J. Mohammed — Deputy Secretary-General of the U.N.

- Bilikiss Adebiyi Abiola — Wecyclers CEO

- Gbemisola Ruqayyah Saraki- Politician and philanthropist

- Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie — Writer

- Florence Ita Giwa — Politician

- Folake Coker — Fashion Designer, Creative Director of Tiffany Amber

- Funke Akindele — Actress

- Genevieve Nnaji — Actress

- Helen Paul — Comedian

- Ireti Doyle — Actress[10]

- Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala — Economist, First Female Minister of Finance

- Osonye Tess Onwueme — Playwright[11]

- Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, activist

- Dora Akunyili - Former Minister of Information and Communication, Former Director General, National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC) of Nigeria.

- Folorunsho Alakija, businesswoman

- Mo Abudu, media personality

- Kemi Adeosun - Minister of Finance (November 2015 - Present)

See also

References

![]()

- ↑ "The Global Gender Gap Report 2013" (PDF). World Economic Forum. pp. 12–13.

- 1 2 "Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in the United States: Updated Estimates of Women and Girls at Risk, 2012" (PDF). Public Health Reports. U.S. Government Printing Office. Mar 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ↑ Audu, B., Geidam, A. and Jarma, H. 2009. Child labor and sexual assault among girls in Maiduguri. Nigeria International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 104:64–67.

- ↑ Okeke, TC; Anyaehie, USB; Ezenyeaku, CCK (2012-01-01). "An overview of female genital mutilation in Nigeria". Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research. 2 (1). doi:10.4103/2141-9248.96942. PMC 3507121. PMID 23209995.

- 1 2 Muteshi, Jacinta K.; Miller, Suellen; Belizán, José M. (2016-01-01). "The ongoing violence against women: Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting". Reproductive Health. 13: 44. doi:10.1186/s12978-016-0159-3. ISSN 1742-4755. PMC 4835878. PMID 27091122.

- ↑ Topping, Alexandra (2015-05-29). "Nigeria's female genital mutilation ban is important precedent, say campaigners". the Guardian. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Audu, B., Geidam, A. and Jarma, H. 2009. Child labor and sexual assault among girls in Maiduguri. Nigeria International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 104:64–67.

- ↑ "Analysis: Nigeria's Sharia split". News.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ "Nigeria: Family Code". Genderindex.org. Archived from the original on 3 December 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ "25 Most Influential Women In Nigeria You Should Know". Nigeria News Online & Breaking News | BuzzNigeria.com. 2015-07-07. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- ↑ "Five most influential Nigerian women of 2016". Retrieved 2017-11-20.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Women of Nigeria. |