Women in law

Women in law describes the role played by women in the legal profession and related occupations, which includes lawyers (also called barristers, advocates, solicitors, attorneys or legal counselors), paralegals, prosecutors (also called District Attorneys or Crown Prosecutors), judges, legal scholars (including feminist legal theorists), law professors and law school deans.

In the US, while women made up 34% of the legal profession in 2014, women are underrepresented in senior positions in all areas of the profession. There has been an increase in women in the law field from the 1970s to 2010, but the increase has been seen in entry level jobs. In the United States, 60% of attorneys are women; however, the percent of female equity partners is 15%.[1] Women of color are even more underrepresented in the legal profession.[2] In private practice law firms, women make up just 4% of managing partners in the 200 biggest law firms.[2] In 2014 in Fortune 500 corporations, 21% of the general counsels were women, of which only 10.5% were African-American, 5.7% were Hispanic, 1.9% were Asian-American/Pacific Islanders, and 0% were Middle Eastern.[2] In 2009, 21.6% of law school Deans were women. Women held 27.1% of all federal and state judge positions in 2012.[2] In the US, "[w]omen of color were more likely than any other group to experience exclusion from other employees, racial and gender stereotyping."[3] There are few women law school deans; the list includes Joan Mahoney, Barbara Aronstein Black at Columbia Law School, Elena Kagan at Harvard Law School, Kathleen Sullivan at Stanford Law School, and the Hon. Kristin Booth Glenn and Michelle J. Anderson at the City University of New York School of Law.

In Canada, while 37.1% of lawyers are women, "50% ...said they felt their [law] firms were doing "poorly" or "very poorly" in their provision of flexible work arrangements."[3] As well, "...racialized women accounted for 16% of all lawyers under 30" in 2006 in Ontario and women Aboriginal lawyers accounted for 1%.[3]

Representation and working conditions

United States

The American Bar Association reported that in 2014, women made up 34% of the legal profession and men made up 66%.[2] In private practice law firms, women make up 20.2% of partners, 17% of equity partners and 4% of managing partners in the 200 biggest law firms.[2] At the junior level of the profession, women make up 44.8% of associates and 45.3% of summer associates.[2] In 2014 in Fortune 500 corporations, 21% of the general counsels were women and 79% were men. Of these 21% of women general counsels, 81.9% were Caucasian, 10.5% were African-American, 5.7% were Hispanic, 1.9% were Asian-American/Pacific Islanders, and 0% were Middle Eastern.[2] In 2009, women were 21.6% of law school Deans, 45.7% of Associate, Vice-Deans or Deputy Deans and 66.2% of Assistant Deans. Women have better representation on law school Law Reviews. In the top 50 schools as ranked by US World and News Reports in 2012-2013, women made up 46% of leadership positions and 38% of editor-in-chief positions.[2]

In 2012, women held 27.1% of all federal and state judge positions, while men held 73.9%.[2] In 2014, three of nine Supreme Court justices were women (33%), 33% of Circuit Court of Appeals judges and 24% of federal court judges.[2] Women held 27% of all state judge positions.

During the 2012-2013 academic year, women made up 47% of Juris Doctor (JD) students, people of color made up 25.8% of JD students.[3] In 2009 in the US, women made up 20.6% of law school deans.[3] In the US in 2014, 32.9% of all lawyers were women.[3] 44.8% of law firm associates were women in 2013.[3] In the 50 "best law firms for women" in the US, "19% of the equity partners were women, 29% of the nonequity partners were women, and 42% of... counsels were women.[3]

A survey indicates that 96% of US law firms state that their highest paid partner is male.[3] "Only 24.1% of all federal judgeships were held by women, and only 27.5% of state judgeships were held by women.:[3] Women lawyers' salaries were "83% of men lawyers’ salaries in 2014".[3]

Canada

In 2010 in Canada, "there were 22,261 practicing women lawyers and 37,617 practicing men lawyers." [3] Canadian studies show that "50% of lawyers said they felt their firms were doing "poorly" or "very poorly" in their provision of flexible work arrangements."[3] More women lawyers found it "difficult to manage the demands of work and personal/family life" than men, with 75% of women reporting these challenges versus 66% of men associates.[3] A 2010 report about Ontario lawyers from 1971 to 2006 indicates that "...racialized women accounted for 16% of all lawyers under 30, compared to 5% of lawyers 30 and older in 2006. Visible minority lawyers accounted for 11.5% of all lawyers in 2006. Aboriginal lawyers accounted for 1.0% of all lawyers in 2006.[3]

Women of color

Representation

The National Association for Law Placement (NALP) found that every year since 2009 there has been a decline of African-American associates—“from 4.66 percent to 3.95 percent."[4] According to a November 2015 NALP press release, at just 2.55 percent of partners, minority women remain the most underrepresented group at partnership level.[4]

Treatment

In a 2008 survey, by the National Association of Women Lawyers (NAWL), the report found that women of color view their workplace as racially/ethnically stereotypical and exclusionary as a result. Women of color also felt that law firms were not taking enough action to increase diversity and when actions were taken they were not executed effectively.[5] The America Bar Association Commission on Women in the Profession released a report which was a culmination of a study meant to address the decline of women of color in the legal profession. In the study, women of color were given the opportunity to express concern over the negative effects they faced in the workplace and how those effects carried into their personal life. Women of color reported feelings of exclusion, isolation, and as though they were receiving more unwanted critical attention than their counterparts.[6] The American Bar Association Commission on Women in the Profession when looking at reports on the treatment of women of color in the legal profession were disappointed with the patterns they noticed which led the American Bar Association Commission on Women in the Profession to undertake their own research in 2003, the Women of Color Research Initiative. In both law firms and corporate legal departments the findings were that women of color “receive less compensation than men and white women; are denied equal access to significant assignments, mentoring and sponsorship opportunities; receive fewer promotions; and have the highest rate of attrition.”[4] There is a ripple effect within the treatment of women of color. Women of color are put at a disadvantage early on making “the ultimate result that women of color miss opportunities to get better work assignments, more client contact, and more billable hours.”[6] Women of color’s treatment within the legal profession and their feelings about this treatment have affected the retention of women of color in the legal profession. Women of color leave law firms at a high rate, “nearly 75 percent leave by their fifth year, and nearly 86 percent leave before their seventh year."[5] These women are leaving because they feel the only way to escape exclusion in the workplace is to leave the workplace.

Strategy

ABA's Commission on Women in the Profession released a report aimed at identifying challenges faced by women of color in law firms and found that “to overcome systemic discrimination against women of color, firms must recognize that the experiences of women of color are different from those of other groups; implementing changes to reflect this difference is necessary for retention. Firms and corporations must initiate active mentorship programs and encourage organization-wide discussions about issues concerning women of color, and constructive feedback is required.”[6] After the release of this report, several law firms have attempted the recommendations set forth by the report. Law firms began initiatives that focus on recruiting women of color as well as ensuring the retention of women of color as well. Recruiting of minority women has been increased through law firms finding summer associates by doing interviews “at the Southeast Minority Career Fair, MCCA/Vault Career Fair, Specialty Bar Association, Lavender Law Career Fair, and at schools such as Howard University School of Law and North Carolina Central School of Law.”[6]

Organizations

Center for Women in Law (US)

The Center for Women in Law is a US organization set up and funded by women, says it is "devoted to the success of the entire spectrum of women in law ... serves as a national resource to convene leaders, generate ideas, and lead change".[7] It combines theory with practice, addressing issues facing individuals and the profession as a whole. The Center is a Vision 2020 National Ally.[8] The Center was founded in 2008 by a group of women, many of whom were alumnae of The University of Texas School of Law, and many of whom graduated from law school in earlier decades when it was not common for women to pursue law as a career. The group began discussing the issues faced by women lawyers and became determined to understand fully and address effectively the underlying causes of the barriers to advancement faced by women lawyers. The Austin Manifesto calls for specific, concrete steps to tackle the obstacles facing women in the legal profession today. The center holds summits and meetings on issues affecting women in the legal profession.

National Women's Law Center (US)

The National Women's Law Center (NWLC) is a United States non-profit organization founded in 1972 and based in Washington, D.C. The Center advocates for women's rights through litigation and policy initiatives. It began when female administrative staff and law students at the Center for Law and Social Policy demanded that their pay be improved, that the center hire female lawyers, that they no longer be expected to serve coffee, and that the center create a women's program.[9] Marcia Greenberger was hired in 1972 to start the program and Nancy Duff Campbell joined her in 1978.[9] In 1981, the two decided to turn the program into the separate National Women's Law Center.[9][10]

Women's Legal Education and Action Fund (Canada)

Women's Legal Education and Action Fund, referred to by the acronym LEAF, is the "...only national organization in Canada that exists to ensure the equality rights of women and girls under the law.".[11] Established on April 19, 1985, LEAF was formed in response to the enactment of Section 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms to ensure that there was fair and unbiased interpretation of women’s Charter rights by the courts. LEAF performs legal research and intervenes in appellate and Supreme Court of Canada cases on women's issues . LEAF has been an intervener in many significant decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada, particularly cases involving section 15 Charter challenges. In addition to its legal work, LEAF also organizes speaking engagements and projects that allow lawyers interested in women’s rights to educate one another, to educate the public, and to create collective responses to legal issues related to women’s equality. LEAF was created by founding mother Doris Anderson and other women.[12]

Women in Law and Litigation (India)

Women in Law and Litigation (WILL) was formed in India in 2014 by women lawyers, judges and legal professionals to deal with gender discrimination faced by women in the field of law. The litigating public prefers to deal with male lawyers.[13] The society was formed under the supervision of Supreme Court of India and the justice of Supreme Court of India, Ranjana Desai.[14] WILL was formed to provide professional support, advocacy skills, and a platform for discussion on ways for development of women lawyers. Justice Hima Kohli of the High Court (Delhi) defined WILL as the society would be a "way to give back to the system for senior lawyers and legal practitioners who have "reached high positions".[13]

Feminist perspectives

Feminist legal theory, also known as feminist jurisprudence, is based on the belief that the law has been fundamental in women's historical subordination.[15] The project of feminist legal theory is twofold. First, feminist jurisprudence seeks to explain ways in which the law played a role in women's former subordinate status. Second, it is dedicated to changing women's status through a reworking of the law and its approach to gender. In 1984 Martha Fineman founded the Feminism and Legal Theory Project at the University of Wisconsin Law School to explore the relationships between feminist theory, practice, and law, which has been instrumental in the development of feminist legal theory.

The liberal model of equality under the law operates from within the liberal legal paradigm and generally embraces liberal values and the rights-based approach to law, though it takes issue with how the liberal framework has operated in practice. The difference model emphasizes the significance of gender differences and holds that these differences should not be obscured by the law, but should be taken into account by it. The dominance model views the legal system as a mechanism for the perpetuation of male dominance. Feminists from the postmodern camp have deconstructed the notions of objectivity and neutrality, claiming that every perspective is socially situated. See equality feminism, difference feminism, radical feminism, and postmodern feminism for context.

Notable scholars include:

Feminist philosophy of law

Feminist philosophy of law "...identifies the pervasive influence of patriarchy on legal structures, demonstrates its effects on the material condition of women and girls, and develops reforms to correct gender injustice, exploitation, or restriction." [16] Feminist philosophy of law uses approaches drawn from "...feminist epistemology, relational metaphysics, feminist political theory, and other developments in feminist philosophy to understand how legal institutions enforce dominant masculinist norms."[16] In the contemporary era, feminist philosophy of law also takes account of approaches such as "...human rights theory, postcolonial theory, critical legal studies, critical race theory, queer theory, and disability studies." [16] As with feminism in general, there are many subtypes of feminist philosophy of law, including "...radical, socialist and Marxist, relational, cultural, postmodern, dominance, difference, pragmatist, and liberal approaches." [16] Feminist philosophers of law argue that "... law makes systemic bias (as opposed to personal biases of particular individuals) invisible, normal, entrenched, and thus difficult to identify and to oppose." [16] Feminist philosophers of law view laws as "...patriarchal, reflecting ancient and almost universal presumptions of gender inequality." [16] Some of the legal issues analyzed by feminist philosophers of law include marriage, reproductive rights (e.g., pertaining to laws on abortion), the "commodification of the body" (as in sex work) and violence against women.[16]

History

In the United Kingdom, the first woman to pass a law degree was Eliza Orme, who graduated from University College London in 1888. She was not allowed to qualify to practice as either a solicitor or a barrister. It was not until 1919, with the passage of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 that women could enter the legal profession. This had been challenged in 1914 in a case known as Bebb v Law Society, in which the Court of Appeal found that women did not fall within the legal definition of "persons" and so could not become lawyers. The 1919 Act also allowed women to serve on juries for the first time.

Notable individuals

United States

- Annette Abbott Adams (1877–1956) was an American lawyer and judge who was the first woman to be the Assistant Attorney General in the United States.[17] She obtained her law degree in 1912. Before beginning her legal career, she was one of the first female school principals in California. In 1950, she served by special assignment on a case in the California Supreme Court, becoming the first woman to sit on that court.[18]

- Florence Ellinwood Allen (1884 – 1966) was an American judge who was the first woman to serve on a state supreme court and one of the first two women to serve as a United States federal judge. She finished a master's degree in Political Science from Western Reserve in 1908.[19] and took courses in constitutional law. She wanted to do a law degree, but at that time, Western Reserve's law school did not admit women. Allen attended the law school at the University of Chicago for a year, and then transferred to New York University. In 1913, she got her law degree, graduating with honors. She became interested in politics, and more committed to the cause of women's suffrage. She began challenging local laws that limited women's participation in the political process. She argued one case that went all the way to the Ohio Supreme Court. In 1919, she was appointed the assistant prosecuting attorney for Cleveland's Cuyahoga County. By 1920, she was elected as a Common Pleas judge. In 1922, Allen was elected to the Ohio Supreme Court. She was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit in 1934, making her one of the first women federal judges.

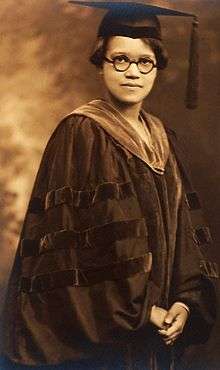

- Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander (1898 – 1989), was the second African-American woman to receive a Ph.D. in the United States, and the first woman to receive a law degree from the University of Pennsylvania Law School. She was the first African-American woman to practice law in Pennsylvania.[20] She was the first African-American woman appointed as Assistant City Solicitor for the City of Philadelphia.

- Helen Elsie Austin (1908–2004) was an American attorney and US foreign service officer who was among the first African Americans admitted to the practice of law in the United States.[21] She received a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1928 and a Bachelor of Laws degree in 1930 from the University of Cincinnati, becoming the first black woman to graduate from the UC Law School.[22] Austin was on the staff of the Rocky Mountain Law Review and of the Cincinnati Law Review.[23] In 1938 she received a Doctor of Laws degree from Wilberforce University. She was the first black woman to serve as Assistant Attorney General in Ohio (1937–38) and became legal advisor to the District of Columbia government in 1939.

- Elreta Melton Alexander-Ralston (1919–1998) was a black female American lawyer and judge in North Carolina at a time when there were only a handful of practising female or black lawyers in that state. She was a trial attorney and District Court Judge. She has remained largely unrecognized. She was the first black woman admitted to Columbia Law School in 1943 at the age of twenty-four. In 1947, Alexander became the first black woman to practice law in North Carolina. In 1968, Alexander became the first black judge elected in North Carolina and only the second black woman to be elected as a judge in the United States.

- Bella Abzug (1920–1998), nicknamed "Battling Bella", was an American lawyer, U.S. Representative, social activist and a leader of the Women's Movement. In 1971, Abzug joined other leading feminists such as Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan to found the National Women's Political Caucus. She was appointed to chair the National Commission on the Observance of International Women's Year and to plan the 1977 National Women's Conference by President Gerald Ford and led President Jimmy Carter's commission on women.

- Joan Mahoney (born 1943) is a legal scholar and former dean of two law schools. She served as Dean at Wayne State University Law School in Detroit, Michigan, from 1998 to 2003, the first woman law school dean in Michigan and one of the very few women in the United States to have held the deanship at two different law schools. Prior to her tenure as Dean at Wayne State, she served from 1994 to 1996 as Dean of Western New England College School of Law in Springfield, Massachusetts. (Women law school deans remain a distinct minority; others have included Barbara Aronstein Black at Columbia Law School, Elena Kagan at Harvard Law School, Kathleen Sullivan at Stanford Law School, and the Hon. Kristin Booth Glenn and Michelle J. Anderson at the City University of New York School of Law). She received her B.A. and M.A. degrees at the University of Chicago, attended Wayne State Law School and received her J.D. there, and received a PhD. from Wolfson College, University of Cambridge in England. A distinguished legal scholar, she has published widely on reproductive rights, constitutional law, legal history, comparative civil liberties, and bioethics.

- Linda Addison (born 1951) is an American lawyer, business executive and author. Addison is Managing Partner, U.S. of Norton Rose Fulbright,[24] chairs the U.S. Management Committee, and serves on its Global Executive Committee.[25] Crain's New York Business named Addison one of the "50 Most Powerful Women in New York" in 2015.[26] She is a founder and Past President of the Center for Women in Law, and co-chaired the New York State Bar Association’s Task Force on the Future of the Legal Profession.[27]

- Anita L. Allen (born 1953)[28] is the Henry R. Silverman Professor of Law and professor of philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. She is also a senior fellow in the bioethics department of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, a collaborating faculty member in African studies, and an affiliated faculty member in the women’s studies program. In 2010 President Barack Obama named Allen to the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues. She is a Hastings Center Fellow. Allen holds a B.A. from New College of Florida. Allen received her M.A. and Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of Michigan. Allen was one of the first African-American women to earn a PhD in Philosophy, along with Adrian Piper. She is the first African-American woman to hold both a J.D. and Ph.D. in philosophy. Allen received her J.D. from Harvard Law.

Canada

At the end of the nineteenth century, Canadian women were barred from participation in, let alone any influence on or control over, the legal system–women could not become lawyers, magistrates, judges, jurors, voters or legislators. Clara Brett Martin (1874 – 1923) became the first female lawyer in the British Empire in 1897 after a lengthy debate in which the Law Society of Upper Canada tried to prevent her from joining the legal profession. After graduating with a Bachelor of Arts in 1891, Martin submitted a petition to the Law Society to become a member. Her petition was rejected by the Society after contentious debate, with the Society ruling that only men could be admitted to the practice of law, because the Society's statute stated that only a "person" could become a lawyer. At that time, women were not considered to be "persons" in Canada, from a legal perspective. W.D. Balfour sponsored a bill that provided that the word "person" in the Law Society's statute should be interpreted to include females as well as males. Martin’s cause was also supported by prominent women of the day including Emily Stowe and Lady Aberdeen. With the support of the Premier, Oliver Mowat, legislation was passed on April 13, 1892, which permitted the admission of women as solicitors.

Helen Kinnear QC (1894 – 1970) was a Canadian lawyer who was the first federally appointed woman judge in Canada. She was the first woman in the British Commonwealth to be created a King's Counsel and the first in the Commonwealth appointed to a county-court bench and the first female lawyer in Canada to appear as counsel before the Supreme Court in Canada in 1935. Marie-Claire Kirkland-Casgrain CM CQ (born 1924) is a Quebec lawyer, judge and politician who was the first woman elected to the Legislative Assembly of Quebec, the first woman appointed a Cabinet minister in Quebec, the first woman appointed acting premier, and the first woman judge to serve in the Quebec Provincial Court. Marlys Edwardh CM (born 1950) is a Canadian litigation and civil rights lawyer who was one of the first women to practice criminal law in Canada.[29] Roberta Jamieson C.M. is a Canadian lawyer and First Nations activist who was the first Aboriginal woman ever to earn a law degree in Canada, the first non-Parliamentarian to be appointed an ex officio member of a House of Commons committee and the first woman appointed as Ontario Ombudsman. Delia Opekokew is a Cree woman from the Canoe Lake First Nation in Saskatchewan, who was the first First Nations lawyer admitted to the law societies in Ontario and in Saskatchewan[30] as well as the first woman ever to run for the leadership of the Assembly of First Nations. Opekokew graduated from Osgoode Hall in 1977, and was admitted to the Bar of Ontario in 1979 and to the Bar of Saskatchewan in 1983.[30]

Beverley McLachlin PC (born 1943) is the 17th and current Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, the first woman to hold this position, and the longest serving Chief Justice in Canadian history. In her role as Chief Justice, she also serves as a Deputy of the Governor General of Canada. When Governor General Adrienne Clarkson was hospitalized for a cardiac pacemaker operation on 8 July 2005, Chief Justice McLachlin served as the Deputy of the Governor General of Canada and performed the duties of the Governor General as the Administrator of Canada.[31] In her role as Administrator, she gave royal assent to the Civil Marriage Act, effectively legalizing same-sex marriage in Canada.[31]

Some Canadian lawyers have become notable for their achievements in politics, including Kim Campbell, Mélanie Joly, Anne McLellan, Rachel Notley and Jody Wilson-Raybould.

Notable Canadian legal professionals include:

- Louise Arbour CC GOQ (born 1947) was the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, a former justice of the Supreme Court of Canada and the Court of Appeal for Ontario and a former Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. She made history with the indictment of a sitting head of state, Yugoslavian president Slobodan Milošević, as well as the first prosecution of sexual assault under the articles of crimes against humanity.

- Kim Campbell PC CC OBC QC (born 1947) is a Canadian politician, diplomat, lawyer and writer who served as the 19th Prime Minister of Canada, from June 25, 1993 to November 4, 1993. Campbell was the first, and to date, only female prime minister of Canada. She earned an LL.B. from the University of British Columbia in 1983.

- Catherine Fraser (born 1947) was appointed as Chief Justice of Alberta and Chief Justice of Northwest Territories in 1992. She was named as the Chief Justice of the Nunavut Court of Appeal on March 24, 1999.

- Jennifer Stoddart (born 1949) was the sixth Privacy Commissioner of Canada. In 1980 she received a licence in civil law from McGill University. As a lawyer she worked to modernize regulations and remove barriers to employment based on gender or cultural differences. She headed the Quebec Commission on Access to Information and held senior positions at the Quebec Human Rights and Youth Rights Commission, the Canadian Human Rights Commission and the Canadian Advisory Council on the Status of Women.[32]

- Martha Hall Findlay (born 1959) is a Canadian businesswoman, entrepreneur, lawyer and politician from Toronto, Ontario. She was elected to the House of Commons of Canada as the Liberal Party of Canada's candidate in a Toronto riding.

- Beth Symes CM [33] Queen's University alumna[34] is a Canadian lawyer[35] who fought the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA, formerly known as Revenue Canada) all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada in order to deduct childcare expenses she incurred to earn income as a partner in her law firm. Symes practised law full-time as a partner in a law firm from 1982-1985.[36] During that period she employed a nanny to care for her children, and deducted the wages paid to the nanny as a business expense on her personal income tax return. Revenue Canada initially allowed these deductions, but later disallowed them. Symes objected to the re-assessment, but CRA denied the objection. Symes appealed to the Federal Court, which ruled that the expenses were valid and legitimate business expenses. The case was appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC), which ruled in Symes v. Canada [1993] that her childcare expenses were not deductible as business expenses.

- Marie Henein is a Canadian lawyer. She is a partner of Henein Hutchison LLP, a law firm in Toronto. Henein has developed a reputation in Toronto as one of the most "respected and feared criminal lawyers in the country."[31] The National Post called her the "most high profile criminal defence lawyer in the country."[37] In 2011, Canadian Lawyer magazine named her one of the "Top 25 Most Influential" saying she was "one of the most sought-after criminal lawyers in the country" and "a key go-to lawyer for high-profile accused in Toronto."[38]

- Anne McLellan PC OC AOE (born 1950) is a Canadian lawyer, academic and politician. She was a cabinet minister in the Liberal governments of Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin, serving as Deputy Prime Minister of Canada. On February 26, 2015, she was appointed chancellor of Dalhousie University[39] effective May 25.[40] She was a professor of law at the University of New Brunswick and the University of Alberta Faculty of Law where she served at various times as associate dean and dean. In 2009, McLellan was appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada for her service as a politician and law professor, and for her contributions as a community volunteer.

- Rachel Notley (born 1964) is a Canadian politician and the 17th and current Premier of Alberta, since 2015. Notley's career before politics focused on labour law, with a specialty in workers' compensation advocacy and workplace health and safety issues.

- Mélanie Joly PC MP (born 1979) is a Canadian lawyer, public relations expert, and politician. She is a Liberal member of the House of Commons of Canada representing Ahuntsic-Cartierville and also serves as the Minister of Canadian Heritage in the Cabinet, headed by Justin Trudeau.

- Jody Wilson-Raybould PC MP (born 1971) is a Kwakwaka’wakw Canadian politician and the Liberal Member of Parliament for the riding of Vancouver Granville. She was sworn in as Minister of Justice of Canada on November 4, 2015; the first Indigenous person to be named to that post. Before entering Canadian federal politics, she was a provincial Crown prosecutor, B.C. Treaty Commissioner and Regional Chief of the B.C. Assembly of First Nations. She earned a law degree from the University of British Columbia Faculty of Law.

United Kingdom

- Brenda Hale, Baroness Hale of Richmond was the first, and only, Lord Justice of Appeal in Ordinary, and following the creation of the new Supreme Court, she became the first woman to serve as a Justice of the Supreme Court. In 2017, she was appointed as the President of the Supreme Court. She was also the first woman to be appointed to the Law Commission.

- Elizabeth Butler-Sloss, Baroness Butler-Sloss was the first woman to be appointed to the Court of Appeal as a Lord Justice of Appeal.

- Ivy Williams was the first woman to be called to the bar, and the first woman to teach law at a British university.

- Carrie Morrison was the first woman solicitor in the United Kingdom.

- Helena Normanton was the first woman to become a barrister in the United Kingdom.

- Eliza Orme was the first woman to graduate with a law degree, in 1888. Women were not allowed to enter the legal profession until 1919 with the passage of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919.

Further reading

- Bartlett, K., 1990. "Feminist Legal Methods," Harvard Law Review, 1039(4): 829–888.

- Bartlett, K. and R. Kennedy (eds.), 1991. Feminist Legal Theory, Boulder: Westview Press.

- Chamallas, M., 2003. Introduction to Feminist Legal Theory, 2d edition, Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Law & Business.

- Frug, M.J., 1992. "Sexual Equality and Sexual Difference in American Law," New England Law Review, 26: 665–682.

- Gould, C., 2003. "Women's Human Rights & the U.S. Constitution," in S. Schwarwenbach and P. Smith (eds.), *Women and the United States Constitution, New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 197–219.

- MacKinnon, C., 2006. Are Women Human?, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Olsen, F. (ed.), 1995. Feminist Legal Theory, New York: New York University Press.

- Manji (eds.), International Law: Modern Feminist Approaches, Oxford and Portland, OR: Hart Publishing.

- Scales, A., 2006. Legal Feminism: Activism, Lawyering and Legal Theory, New York: New York University Press.

- Schwarzenbach, S. and P. Smith (eds.), 2003. Women & the United States Constitution, New York: Columbia University Press.

- Sen, A., 1995. "Gender Inequality & Theories of Justice," in M. Nussbaum and J. Glover (eds.) 1995, pp. 259–273.

- Smith, P., 2005. "Four Themes in Feminist Legal Theory: Difference, Dominance, Domesticity & Denial," in M. Golding and W. Edmundson, Philosophy of Law & Legal Theory, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 90–104.

- –– (ed.), 1993. Feminist Jurisprudence, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Stark, B., 2004. "Women, Globalization, & Law," Pace International Law Review, 16: 333–356.

See also

References

- ↑ Pinnington, Ashly (November 2013). "Lawyers' Professional Careers: Increasing Women's Inclusion in the Partnership of Law Firms". Gender, Work & Organization. 20 (6): 616–631. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "A Current Glance at Women in the Law" (PDF). Americanbar.com. July 2014. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Women in Law in Canada and the U.S." Catalyst.org. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- 1 2 3 Jackson, Liane (March 2016). "Minority Women Are Disappearing from BigLaw--And Here's Why". ABA Journal – via EBSCO Academic Search Complete.

- 1 2 "Women of Color Continue to Face Barriers in U.S. Law Firms, According to Catalyst Report". Diversity Factor. 17. 2009 – via ProQuest.

- 1 2 3 4 Brown, Paulette (January 2009). "Issues and Solutions Affecting Women of Color in the Law". Minority Trial Lawyer. 7 – via EBSCO Academic Search Complete.

- ↑ "Center for Women in Law » About The Center". Utexas.edu. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- ↑ Drexel University, College of Medicine, Vision 2020: national Allies - Center for Women in Law. "Vision 2020 is a national coalition of organizations and individuals united in the commitment to achieve women’s economic and social equality. It was founded and administered by the Institute for Women's Health and Leadership at Drexel University College of Medicine."

- 1 2 3 Naili, Hajer (2012-01-04). "21 Leaders 2012 - Seven Who Leverage Power". Women's eNews. Retrieved 2015-07-10.

- ↑ "Marcia D. Greenberger, Co-President | National Women's Law Center". Nwlc.org. Retrieved 2015-07-10.

- ↑ "Women's Legal Education and Action Fund". Women's Legal Education and Action Fund. Retrieved April 13, 2012.

- ↑ "History of LEAF - Women's Legal Education and Action Fund". Leaf.ca. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- 1 2 "Women lawyers have to work more to prove themselves: SC Judge Desai". Indian Express. 6 September 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ↑ "Women have broken barriers of gender discrimination: SC judge". Zee News. 6 September 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ↑ Fineman, Martha A. "Feminist Legal Theory" (PDF). Journal of Gender, Social Policy and the Law. 13 (1): 13–32. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Feminist Philosophy of Law (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". Plato.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- ↑ Gordon Moris Bakken; Brenda Farrington (26 June 2003). Encyclopedia of Women in the American West. SAGE. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-7619-2356-5. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ↑ "Annette Abbott Adams," Sacramento Lawyer, April 1998, p.11

- ↑ "Florence E. Allen Dies; Retired Federal Jurist". Washington Post. September 14, 1966. pp. B6.

- ↑ "Lawyer Sadie Alexander, a Black pioneer dies at 91". Associated Press. November 3, 1989. Retrieved 2015-09-10.

Sadie Tanner Mosell Alexander, a lawyer and civil rights advocate who achieved many firsts as a black woman, has died of pneumonia at age 91. ...

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved March 31, 2007.

- ↑ "Elsie Austin". Ohio History Central. 2013-05-23. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- ↑ "Global law firm". Norton Rose Fulbright. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- ↑ "Linda L. Addison, Managing Partner". Norton Rose Fulbright. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- ↑ Agovino, Theresa (2016-06-13). "Linda Addison | Most Powerful Women 2015 | Crain's New York Business". Crainsnewyork.com. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- ↑ "New York State Bar Association : Report of the Task Force on the Future of the Legal Profession". Nysba.org. April 2, 2011. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- ↑ date & year of birth, full name according to LCNAF CIP data

- ↑ "Speech by Marlys Edwardh" (PDF). The Law Society of Upper Canada. 2002-02-12. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- 1 2 Cory Toth (2016-05-10). "The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan | Details". Esask.uregina.ca. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- 1 2 3 "Canada's Chief Justice lays down the law | The Journal". www.queensjournal.ca. Retrieved 2015-10-13.

- ↑ "Jennifer Stoddart: making your privacy her business". The Globe and Mail. December 10, 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ↑ "The Governor General of Canada > Find a Recipient". Gg.ca. 2010-11-16. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 28, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ↑ Ediriweera, Himani (1 October 2011). "Beth Symes". Women of Influence. Women of Influence Inc. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ↑ "Canada, Symes v. Canada". Hrcr.org. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- ↑ "'It is not my practice to litigate my cases in the media': Who is Jian Ghomeshi's lawyer Marie Henein?". News.nationalpost.com. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- ↑ "The Top 25 Most Influential". Canadianlawyermag.com. 2011-08-01. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- ↑ "The Honourable Anne McLellan to become Dalhousie's seventh chancellor - Dal News - Dalhousie University". Dal.ca. 2015-02-25. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- ↑ "Ex-deputy PM named Dalhousie chancellor | The Chronicle Herald". Thechronicleherald.ca. Retrieved 2016-06-19.