Women in computing

Women in computing have shaped the evolution of the IT industry. They were among the first programmers in the early-20th century, and contributed substantially to the industry. As technology and practices altered, the role of women as programmers has changed, and the recorded history of the field has downplayed women's achievements.

Since the 18th century, women have developed scientific computations, including Nicole-Reine Lepaute's prediction of Halley's Comet, and Maria Mitchell's computation of the motion of Venus. The first algorithm intended to be executed by a computer was designed by Ada Lovelace who was a pioneer in the field. Grace Hopper was the first person to design a compiler for a programming language. Throughout the 19th and early-20th century, and up to World War II, programming was predominantly done by women; significant examples include the Harvard Computers, codebreaking at Bletchley Park and engineering at NASA.

After the 1960s, the "soft work" that had been dominated by women evolved into modern software, and the importance of women decreased. Many women continued to make significant and important contributions to the IT industry. In the 21st century, women held leadership roles in multiple tech companies, such as Meg Whitman, president and chief executive officer of Hewlett Packard Enterprise, and Marissa Mayer, president and CEO of Yahoo! from July 2012 to June 2017 and previously a long-time executive, usability leader, and key spokesperson at Google.

History

1700s

Nicole-Reine Etable de la Brière Lepaute was one of a team of human computers who worked with Alexis-Claude Clairaut and Joseph-Jérôme Le Français de Lalande to predict the date of the return of Halley's Comet.[1] The group of friends began to work on the calculations in 1757, working throughout the day and sometimes while they ate.[2] The method of computing that they used was followed by successive human computers.[3] They divided large calculations into "independent pieces, assembled the results from each piece into a final product" and then checked for errors.[3] Lepaute continued to work on computing for the rest of her life, working for the Connaissance de Temps and publishing predictions of solar eclipses.[4]

1800s

One of the first computers for the American Nautical Almanac was Maria Mitchel.[5] Her work on the assignment was to compute the motion of the planet Venus.[6] The Almanac never became a reality, but Mitchell became the first astronomy professor at Vassar.[7]

Ada Lovelace was the first person to publish an algorithm intended to be executed by the first modern computer, the Analytical Engine created by Charles Babbage. As a result she is often regarded as the first computer programmer.[8][9][10] Lovelace was introduced to Babbage's difference engine when she was 17.[11] In 1840, she wrote to Babbage and asked if she could become involved with his first machine.[12] By this time, Babbage had moved on to his idea for the Analytical Engine.[13] A paper describing the Analytical Engine, Notions sur la machine analytique, published by L.F. Menabrea, came to the attention of Lovelace, who not only translated it into English, but corrected mistakes made by Menabrea.[14] Babbage suggested that she expand the translation of the paper with her own ideas, which, signed only with her initials, AAL, "synthesized the vast scope of Babbage's vision."[15] Lovelace imagined the kind of impact of the Analytical Engine might have on society.[16] She drew up explanations of how the engine could handle inputs, outputs, processing and data storage.[17] She also created several proofs to show how the engine would handle calculations of Bernoulli Numbers on its own.[17] The proofs are considered the first examples of a computer program.[17][8] Lovelace downplayed her role in her work during her life, for example, in signing her contributions with AAL so as not be "accused of bragging."[18]

After the Civil War in the United States, more women were hired as human computers.[19] Many were war widows looking for ways to support themselves.[19] Others were hired when the government opened positions to women because of a shortage of men to fill the roles.[19]

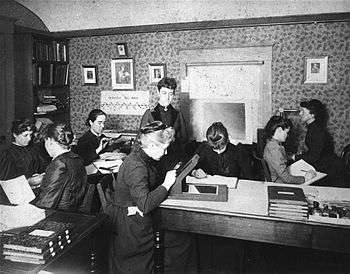

Anna Winlock asked to become a computer for the Harvard Observatory in 1875 and was hired to work for 25 cents an hour.[20] By 1880, Edward Charles Pickering had hired several women to work for him at Harvard because he felt that women could do the job as well as men and he could ask them to volunteer or work for less pay.[21][20] The women, described as "Pickering's harem" and also as the Harvard Computers, performed clerical work that the male employees and scholars considered to be tedious at a fraction of the cost of hiring a man.[22] The women working for Pickering cataloged around ten thousand stars, discovered the Horsehead Nebula and developed the system to describe stars.[23] One of the "computers," Annie Jump Cannon, could classify stars at a rate of three stars per minute.[23] The work for Pickering became so popular that women volunteered to work for free even when the computers were being paid.[24] Even though they performed an important role, the Harvard Computers were paid less than factory workers.[23]

By the 1890s, women computers were college graduates looking for jobs where they could use their training in a useful way.[25] Florence Tebb Weldon, was part of this group and provided computations relating to biology and evidence for evolution, working with her husband, W.F. Raphael Weldon.[26] Florence Weldon's calculations demonstrated that statistics could be used to support Darwin's theory of evolution.[27] Another human computer involved in biology was Alice Lee, who worked with Karl Pearson.[28] Pearson hired two sisters to work as part-time computers at his Biometrics Lab, Beatrice and Frances Cave-Brown-Cave.[29]

1910s

During World War I, Karl Pearson and his Biometrics Lab helped produce ballistics calculations for the British Ministry of Munitions.[30] Beatrice Cave-Brown-Cave helped calculate trajectories for bomb shells.[30] In 1916, Cave-Brown-Cave left Pearson's employ and started working full-time for the Ministry.[31] In the United States, women computers were hired to calculate ballistics in 1918, working in a building on the Washington Mall.[32] One of the women, Elizabeth Webb Wilson, worked as the chief computer.[33] After the war, women who worked as ballistics computers for the U.S. government had trouble finding jobs in computing and Wilson eventually taught high school math.[34]

1920s

_(14570000517).jpg)

In the early 1920s, Iowa State College, professor George Snedecor worked to improve the school's science and engineering departments, experimenting with new punch-card machines and calculators.[35] Snedecor also worked with human calculators most of them women, including Mary Clem.[36] Clem coined the term "zero check" to help identify errors in calculations.[36] The computing lab, run by Clem, became one of the most powerful computing facilities of the time.[36][37]

Women computers also worked at the American Telephone and Telegraph company.[38] These human computers worked with electrical engineers to help figure out how to boost signals with vacuum tube amplifiers.[38] One of the computers, Clara Froelich, was eventually moved along with the other computers to their own division where they worked with a mathematician, Thornton Fry, to create new computational methods.[38] Froelich studied IBM tabulating equipment and desk calculating machines to see if she could adapt the machine method to calculations.[39]

1930s

The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) which became NASA hired a group of five women in 1935 to work as a computer pool.[40] The women worked on the data coming from wind tunnel and flight tests.[40]

1940s

"Tedious" computing and calculating was seen as "women's work" through the 1940s.[41] The history of using women as computers resulted in the term "kilogirl", invented by a member of the Applied Mathematics Panel in the early 1940s.[42] A kilogirl of energy was "equivalent to roughly a thousand hours of computing labor."[42] While women's contributions to the United States war effort during World War II was championed in the media, their roles and the work that women did was still minimized.[43] This included minimizing the complexity, skill and knowledge needed to work on computers or work as human computers.[43] During WWII, women did most of the ballistics computing, seen by male engineers as being below their level of expertise.[44] Black women computers worked as hard (or more often, twice as hard) as their white counterparts, but in segregated situations.[45] By 1943, almost all people employed as computers were women.[46]

NACA expanded its a pool of women working as human computers in the 1940s.[47] NACA recognized in 1942 that "the engineers admit themselves that the girl computers do the work more rapidly and accurately than they could."[40] In 1943, there were two groups, segregated by race working on the East and West side of Langley Air Force Base.[47] The black women were the West Area Computers.[47]

Women also did cryptography work and many went on to operate and work on the Bombe machines after some initial resistance to the idea.[48] Joyce Aylard was one of operators of the Bombe machine where she tested different methods to break the Enigma code.[49] Joan Clarke was one of the cryptographers who worked with her friend, Alan Turing, on the Enigma Machine at Bletchley Park.[50] When she was promoted to a higher salary grade, there were no positions in civil service for a "senior female cryptanalyst," so she was listed as a linguist instead.[51] While Clarke developed a method to increase the speed of double-encrypted messages, unlike many of the men, her decryption technique was not named after her.[52] Other cryptographers who worked at Bletchley included Margaret Rock, Mavis Lever, Ruth Briggs and Kerry Howard.[50] In 1941, Mavis Batey's work there enabled the Allies to break the Italian's Naval code before the Battle of Cape Matapan.[53]

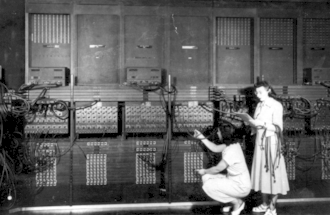

The programmers of the ENIAC computer in 1944, were six female mathematicians; Marlyn Meltzer, Betty Holberton, Kathleen Antonelli, Ruth Teitelbaum, Jean Bartik, and Frances Spence who were human computers at the Moore School's computation lab.[54] Adele Goldstine was their teacher and trainer and they were known as the "ENIAC girls."[55] The women who worked on ENIAC were warned that they would not be promoted into professional ratings; only men were given professional ratings.[56] Designing the hardware "men's work" and programming the software was "women's work."[57] Sometimes women were given blueprints and wiring diagrams to figure out how the machine worked and how to program it.[58] They learned how the ENIAC worked by repairing it, sometimes crawling through the computer, and by fixing "bugs" in the machinery.[58] Even though the programmers were supposed to be doing the "soft" work of programming, in reality, they did that and fully understood and worked with the hardware of the ENIAC.[59] When the ENIAC was revealed in 1946, Goldstine and the other women prepared the machine and the demonstration programs it would run for the public.[60] None of their work in preparing the demonstrations would make it to the official accounts of the public events.[61] After the demonstration, the university hosted an expensive celebratory dinner to which none of the ENIAC six were invited.[62]

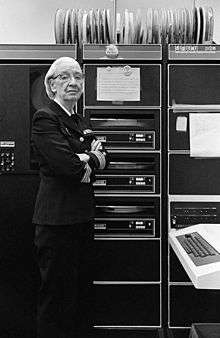

Grace Hopper was the first person to create a compiler for a programming language and one of the first programmers of the Harvard Mark I computer, an electro-mechanical computer based on Analytical Engine. Hopper's work with computers started in 1943, when she started working at the Bureau of Ordnance's Computation Project at Harvard where she programmed the Harvard Mark I.[46] Hopper not only programmed the computer, but created a 500 page comprehensive manual for it.[63] Even though Hopper created the manual which was widely cited and published, she was not specifically credited in the manual.[63] Hopper is often credited with the coining of the term "bug" and "debugging" when a moth caused the Mark II to malfunction.[64] While a moth was found and the process of removing it called "debugging," the terms were already part of the language of programmers.[64][65][66]

1950s

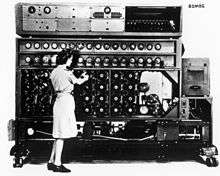

Grace Hopper's contributions to computer science continued through the 1950s. She brought the idea of using compilers from her time at Harvard to UNIVAC which she joined in 1949.[67][64] Other women who were hired to program UNIVAC included Adele Mildred Koss, Frances E. Holberton, Jean Bartik, Frances Morello and Lillian Jay.[56] To program the UNIVAC, Hopper and her team used the FLOW-MATIC programming language, which she developed.[64] Holberton wrote a code, C-10, that allowed for keyboard inputs into a general-purpose computer.[68] Holberton also developed the Sort-Merge Generator in 1951 which was used on the UNIVAC I.[56] The Sort-Merge Generator marked the first time a computer "used a program to write a program."[69] Holberton suggested that computer housing should be beige or oatmeal in color which became a long-lasting trend.[69] Koss worked with Hopper on various algorithms and a program that was a precursor to a report generator.[56]

The NACA, and subsequently NASA, recruited women computers following World War II.[40] By the 1950s, a team was performing mathematical calculations at the Lewis Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio, including Annie Easley, Katherine Johnson and Kathryn Peddrew.[70]

At Convair Aircraft Corporation, Joyce Currie Little was one of the original programmers for analyzing data received from the wind tunnels.[71] She used punch cards on an IBM 650 which was located in a different building from the wind tunnel.[71] To save time in the physical delivery of the punch cards, she and her colleague, Maggie DeCaro, put on roller skates to get to and from the building faster.[71]

In Israel, Thelma Estrin worked on the design and development of WEIZAC, one of the world's first large-scale programmable electronic computers.[72] In the Soviet Union the IT industry was dominated by women; a team of them designed the first digital computer in 1951.[73]

1960s

Adele Mildred Koss, who had worked at UNIVAC with Hopper, started work at Control Data Corporation (CDC) in 1965.[56] There she developed algorithms for graphics, including graphic storage and retrieval.[56]

Mary K. Hawes of Burroghs Corporation set up a meeting in 1959 to discuss the creation a computer language that would be shared between businesses.[74] Six people, including Hopper, attended to discuss the philosophy of creating a common business language (CBL).[74] Hopper became involved in developing COBOL (Common Business Oriented Language) where she innovated new symbolic ways to write computer code.[63] Hopper developed programming language that was easier to read and "self-documenting."[75] After COBOL was submitted to the CODASYL Executive Committee, Betty Holberton did further editing on the language before it was submitted to the Government Printing Office in 1960.[74] IBM were slow to adopt COBOL, which hindered its progress but it was accepted as a standard in 1962, after Hopper had demonstrated the compiler working both on UNIVAC and RCA computers.[76] The development of COBOL led to the generation of compilers and generators, most of which were created or refined by women such as Koss, Nora Moser, Deborah Davidson, Sue Knapp, Gertrude Tierney and Jean E. Sammet.[77]

Sammet, who worked at IBM starting in 1961 was responsible for developing the programming language, FORMAC.[74] She published a book, Programming Languages: History and Fundamentals, which was considered the "standard work on programming languages," according to Denise Gürer [74] It was "one of the most used books in the field," according to The Times in 1972.[78]

In 1964, the British Prime Minister Harold Wilson announced a "White-Hot" revolution in technology, that would give greater prominence to IT work. As women still held most computing and programming positions at this time, it was hoped that it would give them more positive career prospects.[79] In 1965, Sister Mary Kenneth Keller became the first American woman to earn a doctorate in computer science.[80] Keller helped develop BASIC while working as a graduate student at Dartmouth, where the university "broke the 'men only' rule" so she could use its computer science center.[81]

Christine Darden began working for NASA's computing pool in 1967 having graduated from the Hampton Institute.[82] Women were involved in the development of Whirlwind, including Judy Clapp.[56] She created the prototype for an air defense system for Whirlwind which used radar input to track planes in the air and could direct aircraft courses.[56]

In 1969, Elizabeth "Jake" Feinler, who was working for Stanford, made the first Resource Handbook for ARPANET.[83] This led to the creation of the ARPANET directory, which was built by Feinler with a staff of mostly women.[84] Without the directory, "it was nearly impossible to navigate the ARPANET."[85]

By the end of the decade, the general demographics of programmers had shifted away from being predominantly women, as they had before the 1940s.[86] Though women accounted for around 30 to 50 percent of computer programmers during the 1960s, few were promoted to leadership roles and women were paid significantly less than their male counterparts.[87] Cosmopolitan ran an article in the April 1967 issue about women in programming called "The Computer Girls."[88] Even while magazines such as Cosmopolitan saw a bright future for women in computers and computer programming in the 1960s, the reality was that women were still being marginalized.[89]

1970s

_-_NARA_-_558656.tif.jpg)

In the early 1970s, Pam Hardt-English led a group to create a computer network they named Resource One and which was part of a group called Project One.[90] Her idea to connect Bay Area bookstores, libraries and Project One was an early prototype of the Internet.[89] To work on the project, Hardt-English obtained an expensive SDS-940 computer as a donation from TransAmerica Leasing Corporation in April of 1972.[91] They created an electronic library and housed it in a record store called Leopold's in Berkeley.[92] This became the Community Memory database and was maintained by hacker, Jude Milhon.[93] After 1975, the SDS-940 computer was repurposed by Sherry Reson, Mya Shone, Chris Macie and Mary Janowitz to create a social services database and a Social Services Referral Directory.[94] Hard copies of the directory, printed out as a subscription service, were kept at city buildings and libraries.[95] The database was maintained and in use until 2009.[96]

In the early 1970s, Elizabeth "Jake" Feinler, who worked on the Resource Directory for ARPANET, and her team created the first WHOIS directory.[97] Feinler set up a server at the Network Information Center (NIC) at Stanford which would work as a directory that could retrieve relevant information about a person or entity.[97] She and her team worked on the creation of domains, with Feinler suggesting that domains be divided by categories based on where the computers were kept.[98] For example, military computers would have the domain of .mil, computers at educational institutions would have .edu.[99] Feinler worked for NIC until 1989.[100]

Jean E. Sammet served as the first woman president of the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), holding the position between 1974 and 1976.[74]

Adele Goldberg was one of seven programmers that developed Smalltalk in the 1970s, and wrote the majority of the language's documentation. It was one of the first object-oriented programming languages the base of the current graphic user interface,[101] that has its roots in the 1968 The Mother of All Demos by Douglas Engelbart. Smalltalk was used by Apple to launch Apple Lisa in 1983, the first personal computer with a GUI, and a year later its Macintosh. Windows 1.0, based on the same principles, was launched a few months later in 1985.

1980s

As Ethernet became the standard for networking computers locally, Radia Perlman, who worked at Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), was asked to "fix" limitations that Ethernet imposed on large network traffic.[102] In 1985, Perlman came up with a way to route information packets from one computer to another in an "infinitely scalable" way that allowed large networks like the Internet to function.[102] Her solution took less than a few days to design and write up.[102] The name of the algorithm she created is the Spanning Tree Protocol.[103]

In 1988, Stacy Horn, who had been introduced to bulletin board systems (BBS) through The WELL, decided to create her own online community in New York, which she called the East Coast Hang Out (ECHO).[104] Horn invested her own money and pitched the idea for ECHO to others after bankers refused to hear her business plan.[105] Horn built her BBS using UNIX, which she and her friends taught to one another.[106] Eventually ECHO moved an office in Tribeca in the early 1990s and started getting press attention.[107] ECHO's users could post about topics that interested them, chat with on another and were provided email accounts.[108] Around half of ECHO's users were women.[109] ECHO is still online as of 2018.[110]

Computer and video games became popular in the 1980s, but many were primarily action-oriented and not designed from a woman's point of view. Stereotypical characters such as the damsel in distress featured prominently and consequently were not inviting towards women.[111] Dona Bailey designed Centipede, where the player shoots insects, as a reaction to such games, later saying "It didn't seem bad to shoot a bug".[112]

Carol Shaw, considered to be the first modern female games designer, released a 3D version of Tic Tac Toe for the Atari 2600 in 1980.[111] Roberta Williams and her husband Ken, founded Sierra Online and pioneered the graphic adventure game format in Mystery House and the King's Quest series. The games had a friendly graphical user interface and introduced humor and puzzles. Cited as an important game designer, her influenced spread from Sierra to other companies such as LucasArts and beyond.[113][114]

Brenda Laurel worked on porting games from arcade versions to the Atari 400 and Atari 800 computers in the late 1970s and early 1980s.[115] Laurel then went to work for Activision, producing Maniac Mansion.[115]

Despite the pioneering work of some designers, video games are still considered biased towards men. A 2013 survey by the International Game Developers Association revealed only 22% of game designers are women, although this is substantially higher than figures in previous decades.[111]

Adele Goldberg served as president of ACM between 1984 and 1986.[116]

1990s

By the 1990s, computing was dominated by men. The proportion of female computer science graduates peaked in 1984 around 37 per cent, and then steadily declined. Although the end of the 20th century saw an increase in women scientists and engineers, this did not hold true for computing, which stagnated.[117] In 1991, Massachusetts Institute of Technology undergraduate Ellen Spertus wrote an essay "Why Are There So Few Women in Computer Science?", which complained about inherent sexism in IT, which was responsible for a lack of women in computing.[118] She subsequently taught computer science at Mills College, Oakland in order to increase interest in IT for women.[119]

Even if women were starting to be under-represented in computing, women were very involved in working on hypertext and hypermedia projects in the late 1980s and early 1990s.[120] A team of women at Brown University, including Nicole Yankelovich and Karen Catlin, developed Intermedia and invented the anchor link.[121] Apple partially funded their project and incorporated their concepts into Apple operating systems.[122] Sun Microsystems Sun Link Service was developed by Amy Pearl.[122] Janet Walker developed the first system to use bookmarks when she created the Symbolics Document Examiner.[122] In 1989, Wendy Hall created a hypertext project called Microcosm, which was based on digitized multimedia material found in the Mountbatten archive.[123] Cathy Marshall worked on the NoteCards system at Xerox PARC.[124] NoteCards went on to influence Apple's HyperCard.[125] As the Internet became the World Wide Web, developers like Hall adapted their programs to include Web viewers.[126] Her Microcosm was especially adaptable to new technologies, including animation and 3-D models.[127] In 1994, Hall helped organize the first conference for the Web.[128]

Jaime Levy created the one of the first e-Zines in the early 1990s, starting with CyberRag, which included articles, games and animations loaded onto diskettes that anyone with a Mac could access.[129] Later, she renamed the zine to Electronic Hollywood.[129] Billy Idol commissioned Levy to create a disk for his album, Cyberpunk.[129] She was hired to be the creative director of the online magazine, Word, in 1995.[129]

Following the increased popularity of the Internet in the 1990s, online spaces were set up to cater for women, including the online community Women's WIRE[130] and the technical and support forum LinuxChix.[131] Women's WIRE, launched by Nancy Rhine and Ellen Pack in October of 1993, was the first Internet company to specifically target women.[132][133]

Game designer, Brenda Laurel started working at Interval Research in 1992, she began to think about the differences in the way girls and boys experienced playing video games.[134] After interviewing around 1,000 children and 500 adults, she determined that games weren't designed with girls' interests in mind.[135] The girls she spoke with wanted more games with open worlds and characters they could interact with.[136] Her research led to Interval Research giving Laurel's research team their own company in 1996, Purple Moon.[136] Also in 1996, Mattel's game, Barbie Fashion Designer, became the first best-selling game for girls.[137] Purple Moon's first two games based on a character called Rockett, made it to the 100 best-selling games in the years they were released.[138] In 1999, Mattel bought out Purple Moon.[139]

Cyberfeminists, VNS Matrix, made up of Josephine Starrs, Juliane Pierce, Francesca da Rimini and Virginia Barratt, created art in the early 1990s linking computer technology and women's bodies.[140] In 1997, there was a gathering of cyberfeminists in Kassel, called the First Cyberfeminist International.[141]

21st century

In the 21st century, several attempts have been made to reduce the gender disparity in IT and get more women involved in computing again. A 2001 survey found that while both sexes use computers and the internet in equal measure, women were still five times less likely to choose it as a career or study the subject beyond standard secondary education.[142] Journalist Emily Chang said a key problem has been personality tests in job interviews and the belief that good programmers are introverts, which tends to self-select the stereotype of an antisocial white male nerd.[143]

In 2004, the National Center for Women & Information Technology was established by Lucy Sanders to address the gender gap.[144] Carnegie Mellon University has made a concerted attempt to increase gender diversity in the computer science field, by selecting students based on a wide criteria including leadership ability, a sense of "giving back to the community" and high attainment in maths and science, instead of traditional computer programming expertise. As well as increase the intake of women into CMU, the programme resulted in better quality students overall, as they found the increased diversity made for a stronger team.[145]

Turing Award recipients

The Association for Computing Machinery Turing Award, sometimes referred to as the "Nobel Prize" of computing, was named in honor of Alan Turing (1912–1954), a British mathematician and computer scientist. The Turing award has been won by three women between 1966 and 2015.[146]

- 2006 – Francis "Fran" Elizabeth Allen

- 2008 – Barbara Liskov

- 2012 – Shafi Goldwasser

Karen Spärk Jones Award recipients

The British Computer Society Information Retrieval Specialist Group (BCS IRSG) in conjunction with the British Computer Society created an award in 2008 to commemorate the achievements of Karen Spärck Jones, a Professor Emerita of Computers and Information at the University of Cambridge and one of the most remarkable women in computer science. The KSJ award has been won by four women between 2009 and 2017[147].

- 2009 – Mirella Lapata

- 2012 – Diane Kelly

- 2015 – Emine Yilmaz

- 2016 – Jaime Teevan

Notable organizations

- Ada Initiative

- Anita Borg Institute for Women and Technology, group for support of women, runs the Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computing yearly conference.

- Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) Committee on Women

- Association for Women in Computing: one of the first professional organizations for women in computing. AWC is dedicated to promoting the advancement of women in the computing professions.[148]

- BCSWomen, a women-only Specialist Group of the British Computer Society

- Black Girls Code, non-profit focused on providing technology education to young African-American women.

- Center for Women in Technology, university center focused on increasing the representation of women in the creation of technology.

- Computing Research Association's Committee on the Status of Women in Computing Research (CRA-W), group focused on increasing the number of women participating in Computer Science and Engineering (CSE) research and education at all levels.

- Girl Develop It, a nonprofit organization that provides affordable programs for adult women interested in learning web and software development in a judgment-free environment.[149]

- Girl Geek Dinners, an International group for women of all ages.

- Girls Who Code: a national non-profit organization dedicated to closing the gender gap in technology.[150]

- LinuxChix, a women-oriented community in the open source movement.

- National Center for Women & Information Technology, a nonprofit that increases the number of women in technology and computing.[151]

- Systers, a moderated listserv dedicated to mentoring women in the Systers community.

- Women in Technology International, global organization dedicated to the advancement of women in business and technology.

- Women's Technology Empowerment Centre (W.TEC), non-profit organisation focused on providing technology education and mentoring to Nigerian women and girls.[152]

See also

- Gender disparity in computing

- Women in computing in Canada

- African-American women in computer science

- List of female mathematicians

- List of female scientists

- List of organizations for women in science

- List of prizes, medals, and awards for women in science

- List of women in the video game industry

- Timeline of women in computing

- Women in engineering

- Women in science

- Women in the workforce

- Women in venture capital

- Women and video games

References

- ↑ Grier 2013, p. 16.

- ↑ Grier 2013, p. 20-21.

- 1 2 Grier 2013, p. 25.

- ↑ Grier 2013, p. 24.

- ↑ Grier 2013, p. 61.

- ↑ Grier 2013, p. 62.

- ↑ Grier 2013, p. 71.

- 1 2 Fuegi, J.; Francis, J. (2003). Lovelace & Babbage and the creation of the 1843 'notes'. Annals of the History of Computing. 25. pp. 16–26. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2003.1253887.

- ↑ Phillips, Ana Lena (November–December 2011). "Crowdsourcing gender equity: Ada Lovelace Day, and its companion website, aims to raise the profile of women in science and technology". American Scientist. 99 (6): 463.

- ↑ "Ada Lovelace honoured by Google doodle". The Guardian. December 10, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 16.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 17.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 18.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 19.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 19-20.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 Evans 2018, p. 21.

- ↑ Smith 2013, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 Grier 2013, p. 81.

- 1 2 Grier 2013, p. 82.

- ↑ Sobel 2016, p. 13.

- ↑ "How Female Computers Mapped the Universe and Brought America to the Moon". Atlas Obscura. March 4, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Evans 2018, p. 23.

- ↑ Sobel 2016, p. 105.

- ↑ Grier 2013, p. 103.

- ↑ Grier 2013, p. 106.

- ↑ Grier 2013, p. 107.

- ↑ Grier 2013, p. 110.

- ↑ Grier 2013, p. 112.

- 1 2 Grier 2013, p. 130.

- ↑ Grier 2013, p. 131.

- ↑ Grier 2013, p. 138.

- ↑ Grier 2013, p. 139.

- ↑ Grier 2013, p. 152.

- ↑ Grier 2013, p. 165-166.

- 1 2 3 Grier 2013, p. 167.

- ↑ Grier 2013, p. 169.

- 1 2 3 Grier 2013, p. 170.

- ↑ Grier 2013, p. 170-171.

- 1 2 3 4 Atkinson, Joe (2015-08-24). "From Computers to Leaders: Women at NASA Langley". NASA. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- ↑ Mundy 2017, p. 21.

- 1 2 Evans 2018, p. 24.

- 1 2 Light 1999, p. 455-456.

- ↑ Light 1999, p. 460.

- ↑ Shetterly 2016, p. 47-48.

- 1 2 Smith 2013, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 Shetterly 2016, p. 39.

- ↑ Fessenden, Marissa. "Women Were Key to WWII Code-Breaking at Bletchley Park". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- ↑ Bearne, Suzanne (2018-07-24). "Meet the female codebreakers of Bletchley Park". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- 1 2 Miller, Joe (2014-11-10). "The woman who cracked Enigma cyphers". BBC News. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- ↑ Pretz, Kathy (5 February 2015). "Women Code Breakers: Forgotten by History". The Institute. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- ↑ Condie, Bill (14 May 2015). "Joan Clarke, one of the forgotten women of Bletchley". Cosmos. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- ↑ Porzucki, Nina (23 December 2014). "Alan Turing may have cracked Nazi codes, but thousands of women helped". Public Radio International. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 39.

- ↑ Light 1999, p. 459.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Gürer 1995, p. 177.

- ↑ Light 1999, p. 469.

- 1 2 Light 1999, p. 470.

- ↑ Light 1999, p. 471.

- ↑ Light 1999, p. 472.

- ↑ Light 1999, p. 473.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 51.

- 1 2 3 Smith 2013, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 Gürer 1995, p. 176.

- ↑ "Moth in the machine: Debugging the origins of 'bug'". Computerworld. 3 September 2011. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- ↑ Pearson, Gwen (9 December 2013). "Google Honors Grace Hopper...and a "bug"". WIRED. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- ↑ Ceruzzi 1998, p. 84-85.

- ↑ "Frances Holberton, Pioneer in Computer Languages, Dies". The Courier-Journal. 12 December 2001. Retrieved 2018-10-13 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Evans 2018, p. 59.

- ↑ Edwards & Harris 2016, pp. 6,10.

- 1 2 3 Gürer 1995, p. 182.

- ↑ Gürer 1995, p. 178.

- ↑ Abbate 2012, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gürer 1995, p. 179.

- ↑ Ceruzzi 1998, p. 92.

- ↑ Marx 2004, p. 60.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 73.

- ↑ "Computer Authority to Speak Here". The Times. 9 April 1972. Retrieved 2018-10-13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Hicks 2017, p. 14.

- ↑ Gürer 1995, p. 180.

- ↑ Gürer 1995, p. 180-181.

- ↑ Edwards & Harris 2016, p. 50.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 112.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 113.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 116.

- ↑ Hicks 2017, p. 1.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 76-77.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 75.

- 1 2 Evans 2018, p. 76.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 100.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 98.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 101.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 102.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 104-105.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 106-107.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 107.

- 1 2 Evans 2018, p. 119.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 120.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 120-121.

- ↑ Metz, Cade (18 June 2012). "Before Google and GoDaddy, There Was Elizabeth Feinler". WIRED. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- ↑ "Adele Goldberg". University of Maryland, College Park. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Evans 2018, p. 126.

- ↑ Rosen, Rebecca J. (2014-03-03). "Radia Perlman: Don't Call Me the Mother of the Internet". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2018-10-15.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 134.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 135.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 135-136.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 136.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 137.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 139.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 144.

- 1 2 3 Suellentrop, Chris (October 20, 2014). "Saluting the Women Behind the Screen". New York Times. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

- ↑ Ortutay, Barbara (29 June 2012). "Iconic Atari turns 40, tries to stay relevant". Yahoo! News. Associated Press.

- ↑ Loguidice, Bill; Barton, Matt (2012). Vintage Games: An Insider Look at the History of Grand Theft Auto, Super Mario, and the Most Influential Games of All Time. Taylor & Francis. p. 215. ISBN 978-1-136-13757-0.

- ↑ Eschner, Kat (February 16, 2017). "The Pioneer of Graphic Adventure Games Was a Woman". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

- 1 2 Evans 2018, p. 226.

- ↑ "Adele Goldberg, Founding Chairman, ParcPlace Systems, Inc". WITI - Women in Technology Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- ↑ Abbate 2012, p. 145.

- ↑ Abbate 2012, p. 150.

- ↑ Hafner, Katie (August 21, 2003). "3 Women, 3 Paths, 10 Years On". New York Times. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 161.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 161-162.

- 1 2 3 Evans 2018, p. 162.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 159.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 164.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 164-165.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 169.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 171.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 174.

- 1 2 3 4 Evans, Claire L. "The Untold Story of Jaime Levy, Punk-Rock Cyber-Publishing Pioneer". Intelligencer. Retrieved 2018-10-15.

- ↑ "Wired Women of the Internet". The Paducah Sun. October 16, 1996. Retrieved October 11, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Lisa Bowman (September 15, 1999). "She-geeks confess love for Linux". ZDNet News. Archived from the original on June 25, 2007.

- ↑ "Wired Women of the Internet". The Paducah Sun. October 16, 1996. Retrieved October 11, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 206.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 227-228.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 228.

- 1 2 Evans 2018, p. 229.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 230.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 233.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 235.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 238.

- ↑ Evans 2018, p. 240.

- ↑ Frieze & Quesenberry 2015, p. 15.

- ↑ Chang, Emily (March 17, 2018). "Why sexism is rife in Silicon Valley". The Guardian. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

- ↑ Ericson, Cathie (17 October 2014). "Intrepid Woman: Lucinda (Lucy) Sanders: CEO and Co-founder of the National Center for Women & Information Technology (NCWIT)". The Glass Hammer. Evolved People Media LLC. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- ↑ Frieze & Quesenberry 2015, p. 25-27.

- ↑ "Official ACM Turing award website". amturing.acm.org. ACM. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ↑ "KSJ Award". irsg.bcs.org. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ↑ "Association for Women in Computing". Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ↑ https://www.girldevelopit.com/about

- ↑ https://girlswhocode.com/about-us/

- ↑ https://www.ncwit.org/about

- ↑ "The Women's Technology Empowerment Centre – W.TEC". Retrieved October 26, 2014.

Sources

- Abbate, Janet (2012). Recoding Gender: Women's Changing Participation in Computing. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-30453-5.

- Ceruzzi, Paul E. (1998). History of Computing. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262032551 – via EBSCOhost. (Subscription required (help)).

- Edwards, Sue Bradford; Harris, Duchess (2016). Hidden Human Computers: The Black Women of NASA. ABDO. ISBN 978-1-680-79740-4.

- Evans, Claire L. (2018). Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet. New York: Portfolio/Penguin. ISBN 9780735211759.

- Frieze, Carol; Quesenberry, Jeria (2015). Kicking Butt in Computer Science: Women in Computing at Carnegie Mellon University. Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 978-1-457-53927-5.

- Grier, David Alan (2013). When Computers Were Human. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400849369 – via Project MUSE. (Subscription required (help)).

- Gürer, Denise (1995). "Pioneering Women in Computer Science" (PDF). Communications of the ACM. 38 (1): 45–54.

- Hicks, Marie (2017). Programmed Inequality: How Britain Discarded Women Technologists and Lost Its Edge in Computing. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-03554-5.

- Light, Jennifer S. (1999). "When Computers Were Women". Technology and Culture. 40 (3): 455–483 – via JSTOR. (Registration required (help)).

- Marx, Christy (2004). Grace Hopper: The First Woman to Program the First Computer in the United States. Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-823-93877-3.

- Mundy, Liza (2017). Code Girls: The Untold Story of the American Women Code Breakers of World War II. New York: Hachette Books. ISBN 9780316352536.

- Shetterly, Margot Lee (2016). Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 9780062363596.

- Smith, Erika E. (2013). "Recognizing a Collective Inheritance through the History of Women in Computing". CLCWeb: Comparative Literature & Culture: A WWWeb Journal. 15 (1): 1–9 – via EBSCOhost. (Subscription required (help)).

- Sobel, Dava (2016). The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780143111344.

Further reading

- Cooper, Joel; Weaver, Kimberlee D. (2003). Gender and Computers: Understanding the Digital Divide. Philadelphia: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-4427-9.

- Galpin, Vashti (2002). "Women in computing around the world". ACM SIGCSE Bulletin. 34 (2): 94–100. doi:10.1145/543812.543839.

- Light, Jennifer S. (1999). "When Computers Were Women". Technology and Culture. 40 (3): 455–483.

- Margolis, Jane; Fisher, Allan (2002). Unlocking the Clubhouse: Women in Computing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262632690.

- Martin, Ursula. "Women in Computing in the UK". University of St Andrews. Archived from the original on June 24, 2003.

- Misa, Thomas J., ed. (2010). Gender Codes: Why Women Are Leaving Computing. Wiley/IEEE Computer Society Press. ISBN 978-0-470-59719-4.

- Moses, L. E. (1993). "Our computer science class rooms: Are they friendly to female students?". SIGCSE Bulletin. 25 (3). pp. 3–12.

- Natarajan, Priyamvada, "Calculating Women" (review of Margot Lee Shetterly, Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race, William Morrow; Dava Sobel, The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars, Viking; and Nathalia Holt, Rise of the Rocket Girls: The Women Who Propelled Us, from Missiles to the Moon to Mars, Little, Brown), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXIV, no. 9 (May 25, 2017), pp. 38–39.

- Newitz, Annalee (ed.); Anders, Charlie (ed.) (2006). She's Such a Geek: Women Write About Science, Technology, and Other Nerdy Stuff. Seal Press. ISBN 978-1580051903.

- Varma, Roli; Galindo-Sanchez, Vanessa (2006). "Native American Women in Computing" (PDF). University of New Mexico.

External links

- Carnegie Mellon Project on Gender and Computer Science

- National Center for Women & Information Technology US

- Equate Scotland

- Institute for Women in Trades, Technology and Science

- MNT – Mulheres na Tecnologia Brazil

- Resources related to Women in Computing US

- Society for Canadian Women in Science and Technology

- Women in Science, Engineering, and Technology UK

- Women's Engineering Society UK

- When Women Stopped Coding