Women in Germany

Julie Wilhelmine Hagen-Schwarz's Self portrait (before 1870) | |

| Gender Inequality Index-2015[1] | |

|---|---|

| Value | 0.066 |

| Rank | 9th |

| Maternal mortality (per 100,000) | 6 |

| Women in parliament | 36.9% |

| Females over 25 with secondary education | 96.4% [M: 97.0%] |

| Women in labour force | 73% [M: 83%] |

| Global Gender Gap Index-2016[2] | |

| Value | 0.766 |

| Rank | 13th out of 144 |

The roles of German women have changed throughout history, especially during the past few decades, during which the culture has undergone rapid change.

Historical context

The traditional role of women in German society was often described by the so-called "four Ks" in the German language: Kinder (children), Kirche (church), Küche (kitchen), and Kleider (clothes), indicating that their main duties were bearing and rearing children, attending to religious activities, cooking and serving food, and dealing with clothes and fashion. However, their roles changed during the 20th century. After obtaining the right to vote in 1919, German women began to take on active roles previously performed by men. After the end of World War II, they were labeled as the Trümmerfrauen or "women of the rubble" because they took care of the "wounded, buried the dead, salvaged belongings", and participated in the "hard task of rebuilding war-torn Germany by simply clearing away" the rubble and ruins of war.[3]

Although conservative in many ways, Germany nevertheless differs from other German-speaking regions in Europe, being much more progressive on women's right to be politically involved, compared to neighbouring Switzerland (where women obtained the right to vote in 1971 at federal level,[4] and at local canton level in 1990 in the canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden[5]) and Liechtenstein in 1984. In Germany, there are also strong regional differences; for instance Southern Germany (particularly Bavaria) is more conservative than other parts of Germany; while former East Germany is more supporting of women's professional life than former West Germany.[6]

Marriage and family law

Family law in West Germany, had, until recently, assigned women a subordinate role in relation to their husbands. It was only in 1977 that legislative changes provided for gender equality in marriage.[7] In East Germany however, women had more rights, and were encouraged to participate in the labor force.

In 1977, the divorce law in West Germany underwent major changes, moving from a fault based divorce system to one that is primarily no fault. These new divorce regulations, which remain in force today throughout Germany, stipulate that a no-fault divorce can be obtained on the grounds of one year of de facto separation if both spouses consent, and three years of de facto separation if only one spouse consents. There is also provision for a "speedy divorce" which can be obtained on demand by either spouse, without the necessary separation period, if it is proved in court that the continuation of the marriage would constitute an unreasonable hardship for the petitioner for reasons related to the behavior of the other spouse; this exemption requires exceptional circumstances and is considered on a case-by-case basis.[8][9]

In recent years, in Germany, as in other Western countries, there has been a rapid increase in unmarried cohabitation and births outside of marriage.[10] As of 2014, 35% of births in Germany were to unmarried women.[11] There are, however, marked differences between the regions of the former West Germany and East Germany: significantly more children are born out of wedlock in eastern Germany than in western Germany: in 2012, in eastern Germany 61.6% of births were to unmarried women, but in western Germany only 28.4%.[6]

The views on sexual self-determination, as it relates to marriage, have also changed: for instance until 1969 adultery was a criminal offense in West Germany.[12] It was only in 1997, however, that Germany removed its marital exemption from its rape law, being one of the last Western countries to do so, after a lengthy political battle that started in the 1970s.[13][14]

Professional life

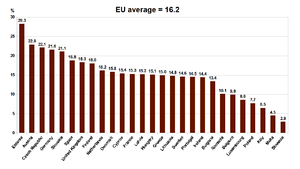

While women in East Germany were encouraged to participate in the workforce, this was not the case in West Germany, where a woman's primary role was understood to be at home, taking care of her family. In recent years, more women are working for pay. Although most women are employed, many work part-time; in the European Union, only the Netherlands and Austria have more women working part-time.[16] One problem that women have to face is that mothers who have young children and want to pursue a career may face social criticism.[17][18] In 2014, the governing coalition agreed to impose a 30% female quota for Supervisory board positions from 2016 onwards.[19]

Compared to other Western and even non-Western countries, Germany has a low proportion of women in business leadership roles, lower even than Turkey, Malaysia, Nigeria, Indonesia, Botswana, India.[20] One of the reasons for the low presence of women in key positions is the social norm that considers full-time work inappropriate for women. Especially Southern Germany is conservative regarding gender roles. In 2011, Jose Manuel Barroso, then president of the European Commission, stated "Germany, but also Austria and the Netherlands, should look at the example of the northern countries [...] that means removing obstacles for women, older workers, foreigners and low-skilled job-seekers to get into the workforce".[21]

Reproductive health and fertility

The maternal mortality rate in Germany is 7 deaths/100,000 live births (as of 2010).[22] The HIV/AIDS rate is 0.1% of adults (aged 15–49) – estimates of 2009.[23] The total fertility rate (TFR) in Germany is 1.44 births per woman (2016 estimates), one of the lowest in the world.[24] Childlessness is quite high: of women born in 1968 in West Germany, 25% stayed childless.[25]

Abortion in Germany is legal during the first trimester on condition of mandatory counseling, and later in pregnancy in cases of medical necessity. In both cases there is a waiting period of 3 days.

Sex education in schools is mandated by law.[26] The German Constitutional Court, and in 2011 the European Court of Human Rights, rejected complaints from several Baptist parents against Germany's mandatory school sex education.[27]

See also

- Open Christmas Letter (To the Women of Germany and Austria)

- Women in Nazi Germany

- Women in German

- Women in German history series

- Alice Schwarzer

- Feminism in Germany

- List of German women writers

- List of German women photographers

- List of German women artists

- List of German queens

- Women in German Studies

- List of German women's football champions

- List of Germany women's international footballers

- Angela Merkel

References

- ↑ "Gender Inequality Index". United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ↑ "The Global Gender Gap Report 2016 – Germany". World Economic Forum.

- ↑ Women In German Society, German Culture, germanculture.com

- ↑ Bonnie G. Smith, ed. (2008). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History. Oxford University Press. pp. 171 vol 1. ISBN 9780195148909.

- ↑ "Naked Swiss hikers must cover up". 27 April 2009. Retrieved 17 April 2018 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- 1 2 http://www.demographic-research.org/volumes/vol33/9/33-9.pdf

- ↑ Reconciliation Policy in Germany 1998–2008, Construing the 'Problem' of the Incompatibility of Paid Employment and Care Work, by Cornelius Grebe; pg 92: "However, the 1977 reform of marriage and family law by Social Democrats and Liberals formally gave women the right to take up employment without their spouses' permission. This marked the legal end of the 'housewife marriage' and a transition to the ideal of 'marriage in partnership'."

- ↑ "Current Legal Framework: Divorce in Germany - impowr.org". www.impowr.org. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ http://ceflonline.net/wp-content/uploads/Germany-Divorce.pdf

- ↑ Ostner, I. (1 April 2001). "Cohabitation in Germany - rules, reality and public discourses". International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family. 15 (1): 88–101. doi:10.1093/lawfam/15.1.88. Retrieved 17 April 2018 – via lawfam.oxfordjournals.org.

- ↑ "Eurostat - Tables, Graphs and Maps Interface (TGM) table". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ "Summary: Adultery in Germany - impowr.org". www.impowr.org. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ http://www.jurawelt.com/sunrise/media/mediafiles/13792/tenea_juraweltbd52_kieler.pdf

- ↑ Breaking Male Dominance in Old Democracies.Oxford University Press 2013. Edt Drude Dahlerup and Monique Leyenaar; pg 205: "Concerning gender equality issues, some policies improved; for example, marital rape was finally prohibited. Germany was until 1997 one of the few post-industrialized countries where marital rape was not forbidden. The law was forced by female politicians from all parties and women's rights activists. In fact, it was one of the few instances where women from all parties supported a proposal, finally convincing the male MPs of their parties to agree. Women had been lobbying for this law for years, but were not heard until the late 1990s, when the number of women in all parties had increased."

- ↑ European Commission. The situation in the EU. Retrieved on 12 July 2011.

- ↑ "Part-time work: A divided Europe". europa.eu. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ Landler, Mark (23 April 2006). "German fights stigma against working mothers". Retrieved 17 April 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

- ↑ "Baby Blues: German Efforts to Improve Birthrate a Failure". 18 December 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2018 – via Spiegel Online.

- ↑ "Germany backs female directors quota". 26 November 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2018 – via www.bbc.com.

- ↑ "Women in business 2015 results". Grant Thornton International Ltd. Home. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "Germany's persistently low birthrate gets marginal boost - DW - 18.08.2011". DW.COM. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ https://www.ined.fr/fichier/s_rubrique/26128/540.population.societies.2017.january.en.pdf

- ↑ Sexualaufklärung in Europa (German)

- ↑ https://sikic.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/admissibility-decision-dojan-and-others-v-germany-1.pdf

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Women of Germany. |