Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti

| Chief Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti MON | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

25 October 1900 Abeokuta, Southern Nigeria (now Abeokuta, Ogun State) |

| Died |

13 April 1978 (aged 77) Lagos, Nigeria |

| Spouse(s) | Israel Oludotun Ransome-Kuti |

| Children |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Occupation | Educator, politician, women's rights activist |

Chief Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, MON ( /ˌfʊnmiˈlaɪjoʊ

Kuti was the mother of the Nigerian activists Fela Anikulapo Kuti, a musician; Beko Ransome-Kuti, a doctor; and Professor Olikoye Ransome-Kuti, a doctor and health minister.[5] She was also grandmother to musicians Seun Kuti and Femi Kuti. She is highly regarded in her native Nigeria for notable acts as an African woman.

Life

Francis Abigail Olufunmilayo Thomas was born on 25 October 1900, in Abeokuta, to Chief Daniel Olumeyuwa Thomas and Lucretia Phyllis Omoyeni Adeosolu of the Jibolu-Taiwo family. Her father was a son of a returned slave from Sierra Leone (see Nova Scotian Settlers), who traced his ancestral history back to Abeokuta in what is today Ogun State, Nigeria.[1][6] He became a member of the Anglican faith, and soon returned to the homeland of his fellow Egbas.

She attended Abeokuta Grammar School for her secondary education, and later went to England for further studies. She soon returned to Nigeria and became a teacher. On 20 January, 1925, she married the Reverend Israel Oludotun, Ransome-Kuti. He also defended the commoners of his country, and was one of the founders of both the Nigeria Union of Teachers and of the Nigerian Union of Students.[6][2]. F. Ransome-Kuti organized literacy classes for Women in the early 1920s and founded a nursery school in the 1930s. She founded the Abeokuta Ladies' Club (ALC) for educated women involved in charitable work in 1942. She also started the social Welfare for Market Women club to help educate working-class women (which formed the first adult education program for women in Nigeria)[7].

Ransome-Kuti received the national honour of membership in the Order of the Niger in 1965. The University of Ibadan bestowed upon her the honorary doctorate of laws in 1968. She also held a seat in the Western House of Chiefs of Nigeria as an Oloye of the Yoruba people.

Activism

Throughout her career, she was known as an educator and activist. She and Elizabeth Adekogbe provided dynamic leadership for women's rights in the 1950s. Ransome-Kuti founded an organization for women in Abeokuta, with a membership tally of more than 20,000 individuals, spanning both literate and illiterate women.[8]

Women's rights

Ransome-Kuti launched the organization into public consciousness when she rallied women against price controls that were hurting the market women. Trading was one of the major occupations of women in the Western Nigeria at the time. In 1949, she led a protest against Native Authorities, especially against the Alake of Egbaland. She presented documents alleging abuse of authority by the Alake, who had been granted the right to collect the taxes by his colonial suzerain, the Government of the United Kingdom. He subsequently relinquished his crown for a time due to the affair. She also oversaw the successful abolishing of separate tax rates for women. In 1953, she founded the Federation of Nigerian Women Societies, which subsequently formed an alliance with the Women's International Democratic Federation.[6] (See also National Council of Women's Societies.)

Funmilayo Ransome Kuti campaigned for women's votes. She was for many years a member of the ruling National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) party, but was later expelled when she was not elected to a federal parliamentary seat. She was the treasurer and subsequent president of the Western NCNC Women's Association.[10]

After her suspension, her political voice was diminished due to the direction of national politics, as both of the more powerful members of the opposition, Awolowo and Adegbenro had her support close by. However, she continued her activism.[11]

In the 1950s, she was one of the few women elected to the house of chiefs. At the time, this was one of her homeland's most influential bodies.

She founded the Egba or Abeokuta Women's Union along with Eniola Soyinka (her sister-in-law and the mother of the Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka).[12] This organisation is said to have once had a membership of 20,000 women. Among other things, Ransome-Kuti organised workshops for illiterate market women.[13] She continued to campaign against taxes and price controls.[12]

Travel ban

During the Cold War and before the independence of her country, Ransome-Kuti travelled widely and angered the Nigerian as well as British and American governments by her contacts with the Eastern Bloc. This included her travel to the former USSR, Hungary and China, where she met Mao Zedong. In 1956, her passport was not renewed by the government because it was said that "it can be assumed that it is her intention to influence … women with communist ideas and policies."[14] She was also refused a U.S. visa because the American government alleged that she was a communist.

Prior to independence she founded the Commoners Peoples Party in an attempt to challenge the ruling NCNC, ultimately denying them victory in her area. She received 4,665 votes to the NCNC's 9,755, thus allowing the opposition Action Group (which had 10,443 votes) to win. She was one of the delegates who negotiated Nigeria's independence with the British government.

Death

In old age her activism was overshadowed by that of her three sons, who provided effective opposition to various Nigerian military juntas. In 1978 Ransome-Kuti was thrown from a third-floor window of her son Fela's compound, a commune known as the Kalakuta Republic, when it was stormed by one thousand armed military personnel.[15] She lapsed into a coma in February of that year, and died on 13 April 1978, as a result of her injuries.[15].

Proposed N5000 note controversy

On Thursday, 30 August 2012, one of her grandsons, musician Seun Kuti, responded to questions from fans and friends on Channels Television, Nigeria’s platform via Google+. Saying that his grandmother was murdered by the Federal Government, Seun Kuti asked the Federal Government to apologise to his family for the death of Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, before considering immortalising her by putting her picture on the proposed N5000 note. As of 3 September 2012, the Nigerian government neither responded to his request nor apologized. Several protest groups formed on social media adding pressure for a government apology.[16] The N5000 proposal was later withdrawn by the Nigerian government.

Achievements

- Took part in the pre-independence conferences that laid the groundwork for Nigeria's First Republic

- One of the women appointed to the native House of Chiefs, serving as an Oloye of the Yoruba people

- Ranking member of the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons

- Treasurer and President Western Women Association of the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons

- Leader of Abeokuta Women's Union.[17][18]

- Leader of Commoners Peoples Party

- Leader of Nigeria Women's Union.

- First woman to drive a car in Nigeria

- Winner of the Lenin Peace Prize[19][20]

Cultural depiction and legacy

Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti was portrayed in the 2014 film October 1 by Deola Sagoe.[21]

She is one of the most prominent figures in Nigerian history and inspired women across Nigeria through her brave acts and most notably her fight for women in the country. Some say that she paved the way for women in Nigeria to have better lives.

References

- 1 2 "Funmilayo Ransome Kuti Nigerian Statesmen".

- 1 2 Johnson-Odim, Cheryl; Mba, Emma (1997). For Women and the Nation: Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti of Nigeria. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06613-8.

- ↑ Modupeolu Faseke (2001). The Nigerian woman: her economic and socio-political status in time perspective. Agape Publications. ISBN 978-9-783-5626-53.

- ↑ Bonnie G. Smith (2005). Women's History in Global Perspective, Volumes 2-3. University of Illinois Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-252-0299-05.

- ↑ "Family tree: jibolu-taiwo-of-egbaland". Archived from the original on 13 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 Margaret Strobel, "Women agitating internationally for change". Journal of Women's History. Baltimore: Summer 2001. Vol. 13, Issue 2; p. 190, 12 pp.

- ↑ "Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti". ZODML. Retrieved 2018-05-23.

- ↑ "Nigerian Biography: Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti. Biography and Activism". www.nigerianbiography.com. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

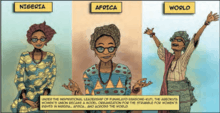

- 1 2 Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti And The Women’s Union of Abeokuta, Illustrations: Alaba Onajin, Script and text: Obioma Ofoego, UNESCO, 2014.

- ↑ Sklar, Richard L. (2004). Nigerian Political Parties: Power in an Emergent African Nation. Africa Research & Publications. ISBN 1-59221-209-3.

- ↑ Joyce M. Chadya, "MOTHER POLITICS: Anti-colonial Nationalism and the Woman Question in Africa". Journal of Women's History. Autumn 2003. Vol. 15, Issue 3; p. 153.

- 1 2 Adeniyi, Dapo. "Monuments and metamorphosis" (PDF). African Quarterly on the Arts Vol. 2, No. 2. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

- ↑ Mama, Amina; Teresa Barnes. "Editorial: Rethinking Universities I" (pdf). Feminist Africa. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

- ↑ "Funmilayo Kuti – 30 Years of Absence". April 2008. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

- 1 2 Gabrielle Eva Marie Zezulka-Mailloux; James Gifford (2003). Culture + the State: Nationalisms (Critical Works from the Proceedings of the 2003 Conference at the University of Alberta). 3. CRC Studio. p. 261. ISBN 978-1-551-9514-92.

- ↑ "Apologise for killing my grandmum before putting her face on naira, Seun Kuti tells FG". Channels Television, Nigeria. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ↑ Judith A. Byfie (2003). "Taxation, Women, and the Colonial State: Egba Women's Tax Revolt". 3 (2). Meridians: feminism, race, transnationalism (Project Muse).

- ↑ Kathleen Sheldon (2016). Historical Dictionary of Women in Sub-Saharan Africa. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 282. ISBN 978-1-442-2629-35.

- ↑ Ian Sansom (11 December 2010). "Great Dynasties: The Ransome-Kutis". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ Johnson-Odim, Cheryl (January–February 2009). "'For their freedoms': The anti-imperialist and international feminist activity of Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti of Nigeria" (PDF). Women's Studies International Forum, special issue: Circling the Globe: International Feminism Reconsidered, 1910 to 1975. Elsevier. 32 (1): 58.

- ↑ Charles Mgolu (13 August 2013). "Late Funmilayo Ransome Kuti resurrects in new movie…'October 1". The Vanguard. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti. |

- Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti And The Women’s Union of Abeokuta, Illustrations: Alaba Onajin, Script and text: Obioma Ofoego, UNESCO, 2014

- Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti

- Biography of Fela Anikulapo Kuti (1938–1997)

- Mhairi McAlpine, "Women on the Left: Funmilayo Anikulapo-Kuti", International Socialist Group, 8 June 2012.