Jain Agamas (Digambara)

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

|

Jain prayers |

|

Ethics |

|

Major sects |

|

Festivals |

|

|

Agamas are texts of Digambara Jainism based on the discourses of the tirthankara. They are all lost now in their original form, with only summary is scattered in the existing texts. Hence, many of the Digambara books end with the word "sara" with means summary to emphasize the fact that these books are only the summaries of particular chapter of Agama, not the original full chapter of Agama in its full length and breadth. Eg Samaysara, Pravachanasara, Niyamsara, Pancastikayasara, Gommatsāra, Rayanasara etc.

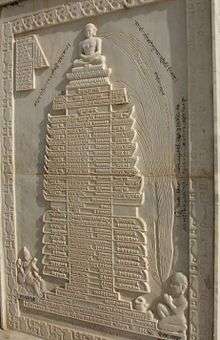

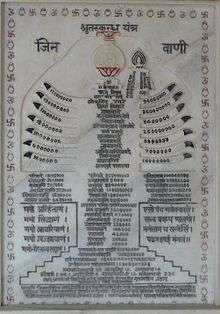

The discourse delivered in a samavasarana (divine preaching hall) is called Śhrut Jnāna and comprises eleven angas and fourteen purvas.[1] The discourse is recorded by Ganadharas (chief disciples), and is composed of twelve angas (departments). It is generally represented by a tree with twelve branches.[2] This forms the basis of the Jaina Agamas or canons. These are believed to have originated from Rishabhanatha, the first tirthankara.[3]

The earliest versions of Jain Agamas known were composed in Ardhamagadhi Prakrit. Agama is a Sanskrit word which signifies the 'coming' of a body of doctrine by means of transmission through a lineage of authoritative teachers.[4]

History

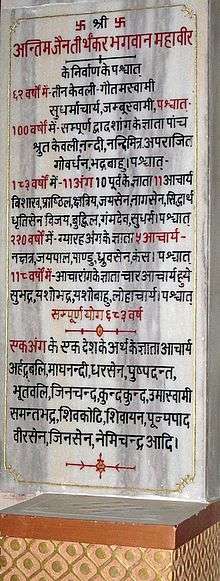

Gautamasvami is said to have compiled the most sacred canonical scriptures comprising twelve parts, also referred to as eleven Angas and fourteen Pūrvas, since the twelfth Anga comprises the fourteen Pūrvas. These scriptures are said to have contained the most comprehensive and accurate description of every branch of learning that one needs to know.[5] The knowledge contained in these scriptures was transmitted orally by the teachers to their disciple saints. Agamas were lost during the same famine that the purvas were lost in.[6] Āchārya Bhutabali was the last ascetic who had partial knowledge of the original canon. Later on, some learned Āchāryas started to restore, compile and put into written words the teachings of Lord Mahavira, that were the subject matter of Agamas.[7] Āchārya Dharasena, in first century CE, guided two Āchāryas, Āchārya Pushpadanta and Āchārya Bhutabali, to put these teachings in the written form. The two Āchāryas wrote, on palm leaves, Ṣaṭkhaṅḍāgama- among the oldest known Digambara Jaina texts. This was about 683 years after the nirvana of Mahavira.

Angas

The knowledge of Shruta-Jnana, may be of things which are contained in the Angas (Limbs or sacred Jain books) or of things outside the Angas.[8]

The Agamas were composed of the following forty-six texts:[9]

- Twelve Angās

- Ācāranga sūtra (now extinct)

- Sūtrakrtanga (now extinct)

- Sthānānga (now extinct)

- Samavāyānga (now extinct)

- Vyākhyāprajñapti (now extinct)

- Jnātrdhārmakathāh (now extinct)

- Upāsakadaśāh (now extinct)

- Antakrddaaśāh (now extinct)

- Anuttaraupapātikadaśāh (now extinct)

- Praśnavyākaranani (now extinct)

- Vipākaśruta (now extinct)

- Drstivāda (now extinct)

- Six Chedasūtras (Texts relating to the conduct and behaviour of monks and nuns)

- Ācāradaśāh (now extinct)

- Brhatkalpa (now extinct)

- Vyavahāra (now extinct)

- Niśītha (now extinct)

- Mahāniśītha (now extinct)

- Jītakalpa (now extinct)

- Four Mūlasūtras (Scriptures which provide a base in the earlier stages of the monkhood)

- Daśavaikālika (now extinct)

- Uttarādhyayana (now extinct)

- Āvaśyaka (now extinct)

- Pindaniryukyti (now extinct)

- Ten Prakīrnaka sūtras (Texts on Independent or miscellaneous subjects)

- Catuhśarana (now extinct)

- Āturapratyākhyanā (now extinct)

- Bhaktaparijñā (now extinct)

- Samstāraka (now extinct)

- Tandulavaicarika (now extinct)

- Candravedhyāka (now extinct)

- Devendrastava (now extinct)

- Ganividyā (now extinct)

- Mahāpratyākhyanā (now extinct)

- Vīrastava (now extinct)

- Two Cūlikasūtras (The scriptures which further enhance or decorate the meaning of Angas)

- Nandī-sūtra (now extinct)

- Anuyogadvāra-sūtra (now extinct)

Jain literature

Digambaras group texts into four literary categories called 'exposition' (anuyoga).[10] The 'first' (prathma) exposition contains Digambara versions of the Universal History; the 'calculation' (karana) exposition contains works on cosmology; the 'behaviour' (charana) exposition includes texts about proper behaviour for monks and lay people; The 'substance' (dravya) exposition includes texts about ontology of the universe and self.[10]

Importance

For Jains, their scriptures represent the literal words of Mahāvīra and the other fordmakers only to the extent that the Agama is a series of beginning-less, endless and fixed truths, a tradition without any origin, human or divine, which in this world age has been channelled through Sudharma, the last of Mahavira's disciples to survive.[11]

Gallery

Stela depicting Jinvani (Śhrut Jnāna)

Stela depicting Jinvani (Śhrut Jnāna) Sacred Jain Books in a Temple Library

Sacred Jain Books in a Temple Library Folio from a Kalpa Sūtra (Book of Sacred Precepts), c. AD 1400

Folio from a Kalpa Sūtra (Book of Sacred Precepts), c. AD 1400 Shrut tradition as per Digambaras

Shrut tradition as per Digambaras

See also

Citations

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. 135.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. 136.

- ↑ Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 12.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, p. 60.

- ↑ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. xi.

- ↑ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 444.

- ↑ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. xii.

- ↑ Jaini 1927, p. 12.

- ↑ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 26.

- 1 2 Dundas 2002, p. 80.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, p. 61.

References

- Cort, John E., ed. (1998), Open Boundaries: Jain Communities and Cultures in Indian History, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-3785-X

- Cort, John E. (2010) [1953], Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-538502-1

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26605-X

- Jain, Champat Rai (1929), Risabha Deva - The Founder of Jainism, Allahabad: The Indian Press Limited,

- Jain, Vijay K. (2011), Acharya Umasvami's Tattvarthsutra (1st ed.), Uttarakhand: Vikalp Printers, ISBN 81-903639-2-1,

- Jain, Vijay K. (2012), Acharya Amritchandra's Purushartha Siddhyupaya: Realization of the Pure Self, With Hindi and English Translation, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-4-5,

- Jaini, Jagmandar Lal (1927), Gommatsara Jiva-kanda

- Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin, eds. (2010), Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, One: A-B (Second ed.), ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-59884-204-3

- Shah, Natubhai (2004) [First published in 1998], Jainism: The World of Conquerors, I, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1938-1

- Singh, Upinder (2016), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson Education, ISBN 978-93-325-6996-6

Further reading

- Stevenson, John (1848), The Kalpa Sutra and Nava Tatva (tr. from Magadhi), Bernard Quaritch, London

- Edward Thomas (1877), Jainism, London, Trübner & co.

- Hermann Jacobi (1884), Jaina Sutras Part I (Akaranga Sutra & Kalpa Sutra), Oxford, The Clarendon press

- Hermann Jacobi (1884), Jaina Sutras Part II (Uttarâdhyayana Sutra & Sutrakritanga Sutra), Oxford, The Clarendon press

- Sinclair Stevenson (1915), The Heart of Jainism, H. Milford: Oxford University Press

- M. S. Ramaswami Ayyangar; B. Seshagiri Rao (1922), Studies in South Indian Jainism, Premier Press, Madras

External links

- www.AtmaDharma.com/jainbooks.html Original Jain Scriptures (Shastras) with Translations into modern languages such as English, Hindi and Gujarati. Literature such as Kundkund Acharya's Samaysaar, Niyamsaar, Pravachansaar, Panchastikay, Ashtphaud and hundreds of others all in downloadable PDF format.

- Jain Agams

- Clay Sanskrit Library publishes classical Indian literature, including a number of works of Jain Literature, with facing-page text and translation. Also offers searchable corpus and downloadable materials.