Nudity in religion

This article on nudity in religion deals with the differing attitudes to nudity and modesty among world religions.

Ancient Greek religion

Hesiod the writer of the poem Theogony, which describes the origins and genealogies of the Greek gods in Ancient Greek religion, suggested that farmers should "Sow naked, and plough naked, and harvest naked, if you wish to bring in all Demeter's fruits in due season."[1] Demeter is the goddess of the harvest and agriculture, who presided over grains and the fertility of the earth.

Abrahamic religions

The Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all recount the legend of the Garden of Eden, found in the Hebrew Bible, in which Adam and Eve are unaware of their nakedness until they eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. After this, they feel ashamed and try to cover themselves with fig leaves.Genesis 3:74 Judaism does not share the Christian association of nakedness with original sin, an aspect integral to the doctrine of redemption and salvation. In Islam the garden is in Paradise, not on Earth. [lower-alpha 1] This is to show that women and men should be covered in clothing, for nudity has the stigma of shame attached to it.[lower-alpha 2] Each of these religions has its own unique understanding of what is meant to be taught with the recounting of the story of Adam and Eve.

Judaism

In Judaism, nudity is an aspect of body modesty which is regarded as very important in most social and familial situations. Attitudes to modesty vary between the different movements within Judaism as well as between communities within each movement. In more strict (orthodox) communities, modesty is an aspect of Tzniut which generally has detailed rules of what is appropriate behaviour. Conservative and Reform Judaism generally promote modesty values but do not regard the strict Tzniut rules as binding, with each person being permitted (at least in principle) to set their own standards. With the exception of the Haredi community, Jewish communities generally tend to dress according to the standards of the society in which they find themselves.

A person who enters a ritual bath (a mikveh) does so without clothing, and with no jewelry or even bandages.

Care needs to be taken when reading the Bible, where some references to nakedness serve as a euphemism for intimate sexual behaviour.[2] For example, in the story of Noah we see the hesitancy of two of Noah's sons when they have to cover their father's nakedness, averting their eyes, after Noah's youngest son "saw his father's nakedness and told his two brothers outside" what he had done to his father.[lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 4] Nakedness may also be a metaphor for empty-handedness, specifically in situations where a sacrifice or offering to God is expected.

Christianity

The early Christian Church reflected the contemporary attitudes of Judaism towards nudity. The Old Testament is not positive towards nudity.[4] In the Old Testament, Isaiah in Isaiah 20 walk nude as a sign of shame against Egypt.

The first recorded liturgy of baptism, written down by Saint Hippolytus of Rome in his Apostolic Tradition, required men, women and children to remove all clothing, including all foreign objects such as jewellery and hair fastenings.[5] Guy (2003), however argues that complete nudity for baptism candidates (especially women) would not be the norm. He notes that at certain times and in certain places candidates may have been totally naked at the point of baptism, but the Jewish taboo of female nakedness would have mitigated widespread practice of naked baptism.

Later Christian attitudes to nudity became more restrictive, and baptisms were segregated by sex and then later were usually performed with clothed participants. Some of the Eastern Orthodox churches today maintain the early church's liturgical use of baptismal nudity, particularly for infants but also for adults.

Several saints, such as a number of the Desert Fathers as well as Basil Fool for Christ, practiced nudity as a form of ascetic poverty.

Early Christian art included depictions of nudity in baptism. When artistic endeavours revived following the Renaissance, the Catholic Church was a major sponsor of art bearing a religious theme, many of which included subjects in various states of dress and including full nudity. Painters sponsored by the Church included Raphael, Caravaggio and Michelangelo, but there were many others. Many of these paintings and statues were and continue to be displayed in churches, some of which were painted as murals, the most famous of which are at the Sistine Chapel painted by Michelangelo.

Smith (1966), in discussing logion 37[lower-alpha 5] of the Gospel of Thomas, notes that early Christian art depicts,[7] as one would expect, Adam and Eve in Paradise naked. The only other Old Testament figures who are depicted nude are Jonah emerging from the mouth of the Great Fish, Daniel emerging from the Lion's Den, and the resurrected in Ezekiel's vision of the dry bones:[8] these Old Testament scenes containing nude figures are precisely those which were held to be types of the resurrection. Among the New Testament illustrations, apart from baptismal scenes, there are nudes only in one representation of the raising of Lazarus and one representation of the Miracle at Cana.

In 1981, Pope John Paul II expressed the Catholic Church's attitude to the exposure of the human body in Love and Responsibility: "The human body can remain nude and uncovered and preserve intact its splendour and its beauty... Nakedness as such is not to be equated with physical shamelessness... Immodesty is present only when nakedness plays a negative role with regard to the value of the person... The human body is not in itself shameful... Shamelessness (just like shame and modesty) is a function of the interior of a person."[9]

Christian sects

Sects have arisen within Christianity from time to time that have viewed nudity in a more positive light. For example, to the Adamites and the Freedomites social nudity was an integral part of their ritual.

Today, Christian naturists maintain that social nudity is a normal part of Christianity and is acceptable. De Clercq (2011) argues that the significance of the human need for clothing by far exceeds its theological meaning.

Islam

In Islam the area of the body not meant to be exposed in public is called the awrah, and while referred to in the Qur'an, is addressed in more detail in hadith.[10][11] In the Sunni tradition, the male awrah is from the navel to knees. Other denominations have differing interpretations. For women, there are different classifications of awrah. In public, many Muslim women wear the hijab and long dresses which covers most of their head and body, with only specific body parts such as hands and face exposed. But in front of direct family (parents, children, siblings), the awrah is relaxed further, allowing them to be uncovered, except between the chest and the thighs. Sharia law in some Islamic countries requires women to observe purdah, covering their entire bodies, including the face (see niqab and burqa), However, the degrees of covering vary according to local custom and/or interpretation of Sharia law.

- For men, the awrah is from the navel (not inclusive) to the knees (not inclusive according to the Shafi'is, Hanbalis and Malikis; inclusive according to the Hanafis). However, in most Islamic cultures, a man is frowned upon should he walk around in public without covering the upper half of his body.

- For women, in front of non-mahram men and non-Muslim women, the awrah is the whole body, apart from the hands and the face (and, solely according to the Hanafis, the feet). In front of Muslim women it is from the navel (not inclusive) to the knees (not inclusive according to the Shafi'is, Hanbalis and Malikis, inclusive according to the Hanafis), and with mahram men there are three opinions:

- It is from the shoulders (inclusive) down to the knees (inclusive). (Hanbali opinion)

- It is from the stomach (inclusive) down to the knees (inclusive according to the Hanafis, but not according to the Shafi'is and Malikis). (Hanafi, Shafi'i, and Maliki opinion)

- It is from the navel (not inclusive) to the knees (inclusive) when with either. (Alternate Hanafi opinion)

Indian religions

In ancient Indian cultures, there was a tradition of extreme asceticism (obviously minoritarian) that included full nudity. This tradition continued from the gymnosophists (philosophers in antiquity) to certain holy men (who may however cover themselves with ashes) in present-day Hindu devotion and in Jainism.

Hinduism

Philosophical basis

The philosophical basis of nudity arises out of the concept of ‘Purushartha’ (four ends of human life). ‘Purushartha’ (Puruṣārtha) are ‘Kama’ (enjoyment), ‘Artha’ (wealth), ‘Dharma’ (virtue) and ‘Moksha’ (liberation). It is ‘Purushartha’ which impels a human being towards nudity or any of its related aspect(s) either for spiritual aim or for the aim of enjoyment. Practice of ‘Dharma’ (virtue) brings good result(s) and non-practice of ‘Dharma’ leads to negative result(s).[13]

Spiritual basis

In the spiritual aspect of Hinduism nudity symbolizes renunciation ('tyaga' in Hindi) of the highest type. A nude person or deity (for example Kali is a nude deity) denotes one who is devoid of Maya or attachment to the body and one who is an embodiment of infinity. [14] Trailanga Swami, the famous nude saint of India, had given an explanation for nudity in religion in the following words, “Lahiri Mahasaya is like a divine kitten, remaining wherever the Cosmic Mother has placed him. While dutifully playing the part of a worldly man, he has received that perfect Self-realization which I have sought by renouncing everything – even my loincloth!”[15]

Material basis

In comparison in the material aspect nudity is considered an art. This view is supported by Sri Aurobindo in his book The Renaissance in India. He says about Hinduism in the book – “Its spiritual extremism could not prevent it from fathoming through a long era the life of the senses and its enjoyments, and there too it sought the utmost richness of sensuous detail and the depths and intensities of sensual experience. Yet it is notable that this pursuit of the most opposite extremes never resulted in disorder…”[16] Extreme hedonists and materialists like the Charvakas are very candid with regard to pursuing of sensual pleasures. They say, “Marthakamaveva purusharthau” (Riches and pleasure is the summum bonum of life). ).[17]There is another sloka in support of their view – “Anganalingananadijanyam sukhameva purusatha” (The sensual pleasure arising from the embrace of a woman and other objects is the highest good or end) ).[18] For non-hedonists pursuing kama (sensual pleasures) accompanied with dharma (virtue) can be the highest ideal or goal in life. There is nothing wrong in it. ).[19]

Occurrence

Some of the famous nude male and female yogi (male and female saints of India) of Hinduism include Lalla Yogishwari (Lalleshwari) [20], Trailanga Swami, Harihar Baba, Tota Puri. [21]Also in the biography of saint Gorakhnath we have reference to nude male and female yogis who had visited the famous Amarnath Temple during medieval period of India.[22]

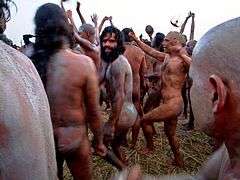

Among the Hindu religious sects, only the sadhus (monks) of the Nāga sect can be seen nude.[23] They usually wear a loin-cloth around their waist, but not always; and usually remain in their Akhara or deep forest or isolation and come out in public only once every four years during Kumbh Mela. They have a very long history and are warrior monks, who usually also carry a talwar (sword), trishul (trident), bhala (javelin) or such weapons, and in medieval times have fought many wars to protect Hindu temples and shrines.[24]

Jainism

In the Digambara sect of Jainism, monks and nuns are "sky-clad" and the members of this sect also keep their holy statues naked. However, the Shwetambar sect is "white-clad" and their holy statues wear a loin cloth.[25]

New religious movements

Neopaganism

In many modern neopagan religious movements, such as Wicca, social and ritual nudity is (relatively) commonplace. In Wicca, the term skyclad refers to ritual nudity instead of social nudity.[26]

Raëlism

In Raëlism, nudity is not problematic. Raëlists in North America have formed GoTopless.org, which organizes demonstrations in support of topfreedom on the basis of the legal and public attitudes to the gender inequality. GoTopless sponsors an annual "Go Topless Day" protest (also known as "National GoTopless Day", "International Go-Topless Day", etc.) in advocacy for women's right to go topless on gender equality grounds.[27]

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ when they tasted of the tree, their shame became manifest to them, and they began to sew together the leaves of the garden over their bodies.[Quran 7:22]

- ↑ O children of Adam! We have indeed sent down to you clothing to cover your shame, and (clothing) for beauty and clothing that guards (against evil), that is the best.[Quran 7:26]

- ↑ [Noah] drank the wine [of his vineyard] and became drunk. He uncovered himself inside his tent. Ham saw his father's nakedness and told his two brothers outside. And Shem and Japheth took a garment, and laid [it] upon both their backs, and went backward, and covered the nakedness of their father; and their faces [were] backward, and they saw not their father's nakedness. And when Noah awoke and learned what [Ham] had done to him, he said "Cursed be Canaan [Ham's son], the lowest of slaves shall he be to his brothers.Genesis 9:21-25

- ↑ it has been suggested that this episode involved Ham doing more than just viewing his father's nakedness.[3]

- ↑ Jesus' disciples ask, "When will you be revealed to us and when will we see you? Jesus said: When you unclothe yourselves without being ashamed and take off your clothes and put them under your feet as little children and tread on them, then [shall you see] the Son of the Living One and you shall not fear"[6]

- ↑ Villing 2010, p. 40.

- ↑ Telushkin 1977, p. 17-18.

- ↑ Edwards 1978, p. 113.

- ↑ Knights 1999.

- ↑ Hippolytus 2013, p. 33.

- ↑ "Gospel of Thomas Translated by Paterson Brown". freelyreceive.net. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ↑ Wilpert 1929.

- ↑ Ezekiel 37:1

- ↑ Wojtyla 2013.

- ↑ "Bukhari:6:60:282".

- ↑ "Sunnan Abu Dawud 32:4091".

- ↑ Bukhari and Muslim

- ↑ Sanyal, Jagdiswar, Guide to Indian Philosophy, Sribhumi Publishing Company, 79, Mahatma Gandi Road, Kolkata – 700 009 (ed. 1999) pp.9 and 14-15

- ↑ Pravrajika Vedantaprana, Saptahik Bartaman, Volume 28, Issue 23, Bartaman Private Ltd., 6, JBS Haldane Avenue, 700 105 (ed. 10 October, 2015) p.16

- ↑ Yogananda, Paramhansa , Autobiography of a Yogi, Chapter 31: An Interview with the Sacred Mother, Jaico Publishing House, 127, Mahatma Gandhi Road Fort, Mumbai - 400 023 (ed. 1997) p. 288

- ↑ SRINVANTU Magazine, 63, College Street, Kolkata – 700 073(ed. 8th June, 2018) pp.26 and 28 (Website: http://srinvantu.com/

- ↑ Sanyal, Jagdiswar, Guide to Indian Philosophy, Sribhumi Publishing Company, 79, Mahatma Gandi Road, Kolkata – 700 009 (ed. 1999) p. 53

- ↑ Sanyal, Jagdiswar, Guide to Indian Philosophy, Sribhumi Publishing Company, 79, Mahatma Gandi Road, Kolkata – 700 009 (ed. 1999) p. 54

- ↑ Sanyal, Jagdiswar, Guide to Indian Philosophy, Sribhumi Publishing Company, 79, Mahatma Gandi Road, Kolkata – 700 009 (ed. 1999) p. 15

- ↑ Yogananda, Paramhansa , Autobiography of a Yogi, Chapter 20: We Do Not Visit Kashmir, Jaico Publishing House, 127, Mahatma Gandhi Road Fort, Mumbai - 400 023 (ed. 1997) p. 195

- ↑ Roy Sankarnath, Bharater Sadhak (Saints of India), 3 and 4, Hare Street, Kolkata – 700 001 (ed. 1980, Volume 7) pp. 187 and 251

- ↑ Roy Sankarnath, Bharater Sadhak (Saints of India), 3 and 4, Hare Street, Kolkata – 700 001 (ed. 1980, Volume 7) p. 16

- ↑ Crooke 1919.

- ↑ Siddharth, Gautam. "Nagas: Once were warriors". Times of India. Times Syndication Service. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ↑ Sharma & Sharma 2004, p. 262.

- ↑ Zimmermann & Gleason 2006, p. 77.

- ↑ Moye, David. "Take Off Your Shirt Everybody! It's Go Topless Day". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- Wilpert, Josef (1929). I Sarcofagi Cristiani Antichi. Rome: Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana.

- Edwards, David Lawrence (1978). A Key to the Old Testament. Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-625192-7.

- Hippolytus (2013). Henry Chadwick & Gregory Dix, ed. The Treatise on the Apostolic Tradition of St Hippolytus of Rome Bishop and Martyr. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-10146-5.

- Sharma, Suresh K.; Sharma, Usha (2004). Cultural and Religious Heritage of India: Jainism. Mittal Publications. ISBN 978-81-7099-957-7.

- Telushkin, Joseph (1977). Biblical Literacy: The Most Important People, Events, and Ideas of the Hebrew Bible. New York: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 978-0-06-201301-9.

- Wojtyla, Karol (2013). Love and Responsibility. Pauline Books & Media. ISBN 978-0-8198-4558-0.

- Knights, C. (1999). "Nudity, Clothing, and the Kingdom of God". The Expository Times. 110 (6): 177–178. doi:10.1177/001452469911000604. ISSN 0014-5246.

- De Clercq, Eva (2011). "The vulnerability of the body: A daring Christian approach to nakedness". Bijdragen. 72 (2): 183–200. doi:10.2143/BIJ.72.2.2131109.

- Smith, Jonathan Z. (Winter 1966). "The Garments of Shame". History of Religions. The University of Chicago Press. 5 (2): 217–238. doi:10.1086/462523. JSTOR 1062112. (Subscription required (help)).

- Guy, Laurie (2003). ""Naked" Baptism in the Early Church: The Rhetoric and the Reality". Journal of Religious History. 27 (2): 133–142. doi:10.1111/1467-9809.00167. ISSN 0022-4227.

- Villing, Alexandra (2010). The Ancient Greeks: Their Lives and Their World. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-985-0.

- Zimmermann, Denise; Gleason, Katherine (2006). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Wicca and Witchcraft. New York: Penguin. ISBN 1592575331.

Further reading

- Ableman, Paul (1982). Anatomy of nakedness. Orbis Pub. ISBN 978-0-85613-175-2.

- Meggitt, Justin (24 January 2011). "Naked Quakers". Fortean Times. Retrieved 2014-08-23.

- Ferguson, Everett (2009). Baptism in the Early Church: History, Theology, and Liturgy in the First Five Centuries. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-2748-7.

- Squire, Michael (2011). The Art of the Body: Antiquity and Its Legacy. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-931-7.

- Smith, Alison (1996). The Victorian Nude: Sexuality, Morality, and Art. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4403-8.

- Miles, Margaret R. (2006). Carnal Knowing: Female Nakedness and Religious Meaning in the Christian West. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59752-901-3.

- Basham, Arthur Llewellyn (1951). History and Doctrines of the Ajivikas, a Vanished Indian Religion. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-1204-8.

- Biaggi, Cristina (1986). "The Significance of the Nudity, Obesity and Sexuality of the Maltese Goddess Figures". In Anthony Bonanno. Archaeology and Fertility Cult in the Ancient Mediterranean: Papers Presented at the First International Conference on Archaeology of the Ancient Mediterranean, University of Malta, 2-5 September 1985. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 90-6032-288-6.

- Le, Dan (2012). The Naked Christ: An Atonement Model for a Body-Obsessed Culture. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-61097-788-3.

- Marinatos, Nanno (2002). Goddess and the Warrior: The Naked Goddess and Mistress of the Animals in Early Greek Religion. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-60148-6.

- Moon, Warren G. (Winter 1992). "Nudity and Narrative: Observations on the Frescoes from the Dura Synagogue". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 60 (4): 587–658. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lx.4.587. JSTOR 1465587.

- Kyriakidis, Evangelos (1997). "NUDITY IN LATE MINOAN I SEAL ICONOGRAPHY". Kadmos. 36 (2). doi:10.1515/kadm.1997.36.2.119. ISSN 0022-7498.

- Keller, Sharon R. (Winter 1993). "Aspects of Nudity in the Old Testament". Source: Notes in the History of Art. Ars Brevis Foundation, Inc. 12 (2): 32–36. JSTOR 23202933.

- Randolph, Vance (Oct–Dec 1953). "Nakedness in Ozark Folk Belief". The Journal of American Folklore. American Folklore Society. 66 (262): 333–339. JSTOR 536729.

- Crooke, W. (Jul–Dec 1919). "Nudity in India in Custom and Ritual". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 49: 237–251. JSTOR 2843441.

- Riley, Gregory J. (2011). "A Note on the Text of Gospel of Thomas 37". Harvard Theological Review. 88 (01): 179–181. doi:10.1017/S0017816000030443. ISSN 0017-8160.

- Mormando, Franco (2008). "Nudus Nudum Christum Sequi: The Franciscans and Differing Interpretations of Male Nakedness in Fifteenth-Century Italy". Fifteenth Century Studies. 33: 171. Archived from the original on 2014-08-19.

- Schafer, Edward H. (June 1951). "Ritual Exposure in Ancient China". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. Harvard-Yenching Institute. 14 (1/2). JSTOR 2718298.