Museum of Science and Industry (Chicago)

|

A view from the lagoon south of the Museum of Science and Industry | |

| Established | 1933 |

|---|---|

| Location |

5700 South Lake Shore Drive (at East 57th Street), Chicago, Illinois, US, 60637 |

| Type | Science and technology museum |

| Visitors | 1.5 million (2016)[1] |

| Public transit access |

CTA Bus routes: Routes 6 and 28 (to 56th Street and Hyde Park Boulevard) Route 10 (to Museum of Science and Industry) Route 55 (to Museum of Science and Industry) Metra Train: 55th–56th-57th Street Station (between Stony Island and Lake Park Avenues) |

| Website |

www |

| Designated | November 1, 1995 |

The Museum of Science and Industry (MSI) is located in Chicago, Illinois, in Jackson Park, in the Hyde Park neighborhood between Lake Michigan and The University of Chicago. It is housed in the former Palace of Fine Arts from the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. Initially endowed by Julius Rosenwald, the Sears, Roebuck and Company president and philanthropist, it was supported by the Commercial Club of Chicago and opened in 1933 during the Century of Progress Exposition.

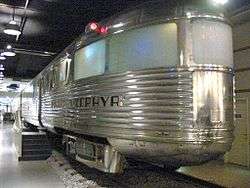

Among the museum's exhibits are a full-size replica coal mine, German submarine U-505 captured during World War II, a 3,500-square-foot (330 m2) model railroad, the command module of Apollo 8, and the first diesel-powered streamlined stainless-steel passenger train (Pioneer Zephyr).

David R. Mosena has been president and CEO of the museum since 1998.[2]

History

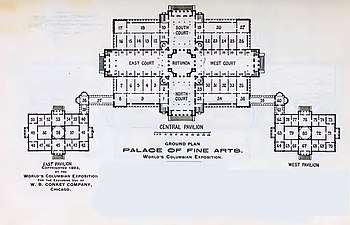

The Palace of Fine Arts (also known as the Fine Arts Building) at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition was designed by Charles B. Atwood for D. H. Burnham & Co. The Palace of Fine Arts displayed paintings, prints, drawing, sculpture, and metal work from around the world.[3]

Unlike the other "White City" buildings, it was constructed with a brick substructure under its plaster facade.

After the World's Fair, it initially housed the Columbian Museum, which evolved into the Field Museum of Natural History. When the Field Museum moved to a new building near downtown Chicago in 1920, the former site was left vacant.

Art Institute of Chicago professor Lorado Taft led a public campaign to restore the building and turn it into another art museum, one devoted to sculpture. The South Park Commissioners (now part of the Chicago Park District) won approval in a referendum to sell $5 million in bonds to pay for restoration costs, hoping to turn the building into a sculpture museum, a technical trade school, and other things. However, after a few years, the building was selected as the site for a new science museum.

At this time, the Commercial Club of Chicago was interested in establishing a science museum in Chicago. Julius Rosenwald, the Sears, Roebuck and Company president and philanthropist, energized his fellow club members by pledging to pay $3 million towards the cost of converting the Palace of Fine Arts (Rosenwald eventually contributed more than $5 million to the project). During its conversion into the MSI, the building's exterior was re-cast in limestone to retain its 1893 Beaux Arts look. The interior was replaced with a new one in Art Moderne style designed by Alfred P. Shaw.

Rosenwald established the museum organization in 1926 but declined to have his name on the building. For the first few years, the museum was often called the Rosenwald Industrial Museum. In 1928, the name of the museum was officially changed to the Museum of Science and Industry. Rosenwald's vision was to create a museum in the style of the Deutsches Museum in Munich, which he had visited in 1911 while in Germany with his family.

Sewell Avery, another businessman, had supported the museum within the Commercial Club and was selected as its first president of the board of directors. The museum conducted a nationwide search for the first director. MSI's Board of Directors selected Waldemar Kaempffert, then the science editor of The New York Times, because he shared Rosenwald's vision.

He assembled the museum's curatorial staff and directed the organization and construction of the exhibits. In order to prepare the museum, Kaempffert and his staff visited the Deutsches Museum in Munich, the Science Museum in Kensington, and the Technical Museum in Vienna, all of which served as models. Kaempffert was instrumental in developing close ties with the science departments of the University of Chicago, which supplied much of the scholarship for the exhibits. Kaempffert resigned in early 1931 amid growing disputes with the second president of the board of directors; they disagreed over the objectivity and neutrality of the exhibits and Kaempffert's management of the staff.

The new Museum of Science and Industry opened to the public in three stages between 1933 and 1940. The first opening ceremony took place during the Century of Progress Exposition. Two of the museum's presidents, a number of curators and other staff members, and exhibits came to MSI from the Century of Progress event.

For years, visitors entered the museum through its original main entrance, but that entrance became no longer large enough to handle an increasing volume of visitors. The newer main entrance is a structure detached from the main museum building, through which visitors descend into an underground area and re-ascend into the main building, similar to the Louvre Pyramid.

In 1983, due to increased attendance, the museum started construction of its underground parking lot, located in three underground levels below the front lawn. Construction of the underground parking lot was finished in the 1990s.

For over 55 years, admission to the MSI was free. Fees were first charged in the early 1990s, with general admission rates increasing from $13 in 2008 to $18 in 2015.[4][5] Many "free days"—for Illinois residents only—are offered throughout the year.[6]

Exhibits

The museum has over 2,000 exhibits, displayed in 75 major halls. The museum has several major permanent exhibits. Access to several of the exhibits (including the Coal Mine and U-505) requires the payment of an additional fee.[5]

Transportation Gallery

The Transportation Zone contains several permanent exhibits.

The Great Train Story is a 3,500-square-foot (330 m2) model railroad and recounts the story of transportation from Chicago to Seattle.

The museum includes a replica of Stephenson's Rocket, which was the first steam locomotive to exceed 25 miles per hour.

The 999 Empire State Express steam locomotive was alleged to be the first vehicle to exceed 100 miles per hour (160 km/h) in 1893, although no reliable measurement ever took place (and such a speed was likely impossible).[lower-alpha 1] Designed to win the battle of express trains to the World's Columbian Exhibition, it was donated to the museum by the New York Central in 1962. The locomotive was located outside the museum until 1993, when extensive restoration took place and it was moved indoors as an exhibit in the Transportation Zone.

A model of the Wright Brothers first airplane is on display.

Two World War II warplanes are also exhibited. Both were donated by the British government: a German Ju 87 R-2/Trop. Stuka divebomber -- one of only two intact Stukas left in the world -- and a British Supermarine Spitfire. Also on display is the museum's Travel Air Type R Mystery Ship, nicknamed "Texaco 13", which set many world records in flying.

"Take Flight" features the first Boeing 727 jet plane in commercial service, donated by United Airlines, with one wing removed and holes cut on the fuselage to facilitate visitor access.

A second transportation gallery is located on the museum's west wing, containing models of "Ships Through the Ages" and several historic racing cars.

Science Storms

In March 2010, the museum opened "Science Storms" in the Allstate Court, as a permanent exhibit.[8] This multilevel exhibit features a 40-foot (12 m) water vapor tornado, tsunami tank, Tesla coil, heliostat system, and a Wimshurst machine built by James Wimshurst in the late 19th century. Also housed are Newton's Cradle, the color spectrum, and Foucault pendulum. All artifacts allow guests to explore the physics and chemistry of the natural world.[9]

Genetics: Decoding Life

In keeping with Rosenwald's vision, many of the exhibits are interactive. "Genetics: Decoding Life", looks at how genetics affect human and animal development as well as containing a chick hatchery composed of an incubator where baby chickens hatch from their eggs and a chick pen for those that have already hatched, as well as housing genetically modified frogs, mice, and drought resistant plants.

"ToyMaker 3000", is a working assembly line which lets visitors order a toy top and watch as it is made. The interactive "Fab Lab MSI" is intended as an interactive lab where members can "build anything".

Coal Mine

The "Coal Mine" re-creates a working deep-shaft, bituminous coal mine inside the museum's Central Pavilion, using original equipment from Old Ben #17 circa 1933.[10] It is one of the oldest exhibits at the museum. In this unique exhibit, visitors go underground and ride a mine train to the different parts of the mine and the basics to it. The experience takes around 40-50 min., and requires an additional fee.

U-505

German submarine U-505 is one of just two German submarines captured during World War II, and, since its arrival in 1954, the only one on display in the Western Hemisphere, as well as the only one in the United States. The U-boat was newly restored beginning in 2004 after 50 years of being displayed outdoors, and was then moved indoors as "The New U-505 Experience" on June 5, 2005. Displayed in a underground shed, it remains as a popular exhibit for visitors, as well as a memorial to all the casualties of the Battle of the Atlantic during World War II.

Entry Hall

The first diesel-powered streamlined stainless-steel train, the Pioneer Zephyr, is on permanent display in the Great Hall, renamed the Entry Hall in 2008. The train was once displayed outdoors, and restored and placed in the former Great Hall during the construction of the museum's underground parking lot. Today, a complimentary tour goes through it every 10–20 minutes.

Henry Crown Space Center

MSI's Henry Crown Space Center includes the Apollo 8 spacecraft, which flew the first mission beyond low earth orbit to the Moon, enabling its crew, Frank Borman, James Lovell and William Anders, to become the first human beings to see the Earth as a whole, as well as becoming the first to view the Moon up close (as well as the first to view its far side). Other exhibits include Scott Carpenter's Mercury-Atlas 7 spacecraft, a Mars Rover (which you can actually control), a lunar module trainer and a life-size mockup of Space Shuttle Atlantis.

Located in the Henry Crown Space Center is a domed theater, considered to be the only domed theater in Chicago. The screen of the theater is made of aluminum, allowing the speakers to be heard around the theater.

Other

The museum is also known for unique and quirky permanent exhibits, such as a walk-through model of the human heart, which was removed in 2009[11] for the construction of "YOU! the Experience",[12] which replaced it with a 13-foot-tall (4.0 m), interactive, 3D heart.[13] Also well known are the "Body Slices" (two cadavers exhibited in 1⁄2-inch-thick (13 mm) slices) in the exhibit.

Several US Navy warship models are also on display in the museum, and flight simulators including of the new F-35 Lightning II are featured.

A F-104 Starfighter on loan to MSI from the US Air Force since 1978 was sent to the Mid-America Air Museum in Liberal, Kansas in 1993. In March 1995, Santa Fe Steam Locomotive 2903 was moved from outside the museum to the Illinois Railway Museum.

In spring 2013, the "Art of the Bicycle" exhibit opened, showcasing history of the bicycle, and how modern bikes are still continuing to evolve.

Other exhibits include "Yesterday's Mainstreet", a mock-up of a Chicago street from the early 20th century, complete with a cobblestone roadway, old-fashioned light fixtures, fire hydrants, and several shops, including the precursors to several Chicago-based businesses. Included are:

- The Berghoff restaurant

- Chicago Post Office

- Commonwealth Edison

- Finnigan's Ice Cream Parlor and Photo Studio

- Gossard Corset Shop

- Jewel Tea Company grocery

- Jenner and Block Law office

- Lytton's Clothing Store

- Dr. John B. Murphy's office

- The Nickelodeon Cinema

- Chas. A. Stevens & Co.

- Walgreens Drug Company

Unlike the other shops, Finnigan's Ice Cream Parlor and The Nickelodeon Cinema can be entered and are functional. Finnigan's serves an assortment of ice cream and The Cinema plays short silent films throughout the day.

The "FarmTech" exhibit showcases modern agricultural techniques and how farmers use modern technology like GPS systems to improve work on the farm, and includes a tractor and a combine harvester from John Deere. The exhibit also showcases a greenhouse, a mock up of a kitchen showcasing much the foods we eat is soybean, and how we use cows, from energy to what we drink.

Other upper level exhibits include "Reusable City", which focuses on recycling and other methods that could cut down harmful pollution and especially climate change and the Regenstein Hall of Science, containing a giant periodic table of the elements. Other main level exhibits include: "Fast Forward", which features some aspects of how technology will change in the future; "NetWorld", which focuses on the Internet and how it connects society together; "Earth Revealed", featuring a "Science on a Sphere" holographic globe; and a "Whispering Gallery".

"Future Energy Chicago" shows alternative resources, housing developments, and the future of Chicago. The exhibit requires an additional fee.

Some areas in the museum aim for younger children, including the "Swiss Jollyball", the world's largest pinball machine built by a British man from Switzerland using nothing but salvaged junk; the "Idea Factory", a toddler water table play area; and the "Circus", featuring animated dioramas of a miniature circus as well as containing a shadow garden and several funhouse mirrors.

Silent-film star and stock-market investor Colleen Moore's Fairy Castle "dolls house" is on display.

Yearly, from late December to early January, the museum hosts its Christmas Around the World Exhibit, having Christmas trees from different cultures from around the world. Started in 1942, with just one tree, honoring soldiers fighting in WW2, the tradition spawned into more than 50 trees.

The museum holds the Junior Achievement's US Business Hall of Fame.[14]

Exhibitions

In addition to its three floors of standing exhibits, the museum hosts temporary and traveling exhibitions. Exhibitions last for five months or less and usually require a separate paid admission fee.[5] Exhibitions at MSI have included Titanic: The Exhibition,[15] which was the largest display of relics from the wreck of RMS Titanic; Gunther von Hagens' Body Worlds, a view into the human body through use of plastinated human specimens; Game On,[16] which featured the history and culture of video games; Leonardo da Vinci: Man, Inventor, Genius;[17] CSI: The Experience; Robots Like Us;[18] City of the Future;[19] Star Wars: Where Science Meets Imagination; The Glass Experience; Harry Potter: The Exhibition;[20] Robot Revolution, which was sponsored by Google and featured numerous hands-on demonstrations and advice from experts for prospective future robot scientists and engineers;[21]and four installments of Smart Home: Green + Wired, featuring the work of green architect Michelle Kaufmann.[22] The next such exhibit, The Science Behind Pixar, is scheduled to open May 24, 2018.[23]

Gallery

See also

References

Explanatory notes

- ↑ Another contender is GWR 3700 Class 3440 City of Truro. The claim of the Empire State Express has little supporting evidence; unlike City of Truro, there are no timings showing the acceleration up to 100 mph. Some contemporary American technical journals doubted that such a high speed had been attained: "Many are disposed to receive with doubt the statement that on 9 May the locomotive No. 999 of the New York Central railroad ran at the speed of 100 miles an hour, or that on a subsequent date she ran a single mile in 32 seconds".[7]

Citations

- ↑ "TEA-AECOM 2016 Theme Index and Museum Index: The Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association. pp. 68–73. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ↑ "Officers and Directors 2011" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 12, 2010. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ↑ Department of Publicity and Promotion (1893). World's Columbian Exposition, 1893: official catalogue. Part X. Department K. Fine arts. Chicago: W.B. Conkey.

- ↑ "Siemens Makes Donation to the Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago". Siemens Corporation. August 13, 2008. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Tickets". Museum of Science and Industry. 2017. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- ↑ "Ticket Prices: 2017 Illinois Free Day Schedule". Museum of Science and Industry. 2017. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- ↑ Allen, Leicester (1893). "Mechanics". Engineering Magazine. 5: 530. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- ↑ "Science Storms". Museum of Science and Industry. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Science Storms News". Museum of Science and Industry. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Coal Mine". Museum of Science and Industry. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ↑ Mullen, William (August 26, 2009). "Museum of Science and Industry Gets a New Heart Display". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 17, 2013.

- ↑ "YOU! The Experience". Museum of Science and Industry. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Your Heart". Museum of Science and Industry. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Chicago Business Hall of Fame". Junior Achievement Chicago. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Titanic: The Exhibition". Museum of Science and Industry. Archived from the original on February 3, 2003. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Archived Exhibits". Museum of Science and Industry. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Leonardo da Vinci: Man – Inventor – Genius". Museum of Science and Industry. Archived from the original on September 25, 2006. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Robots Like Us". Museum of Science and Industry. 2006. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ↑ "The City of the Future: A Design and Engineering Challenge". The History Channel. Archived from the original on July 13, 2009. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Harry Potter: The Exhibition". Museum of Science and Industry. 2009. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ↑ "They, robots: 'Revolution' opens at the MSI". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Smart Home: Green + Wired 2012". Museum of Science and Industry. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Exhibit / The Science Behind Pixar". msichicago.org. Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

Further reading

- Kogan, Herman. A Continuing Marvel: The Story of the Museum of Science and Industry. 1st ed. Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday, 1973.

- Pridmore, Jay. Inventive Genius: The History of the Museum of Science and Industry Chicago. Chicago: Museum of Science and Industry, 1996.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Museum of Science and Industry (Chicago). |

- Museum website

- Commercials and news clips at The Museum of Classic Chicago Television

- High-resolution 360° Panoramas and Images at Columbia University

Coordinates: 41°47′26″N 87°34′58″W / 41.79056°N 87.58278°W