Tamilakam

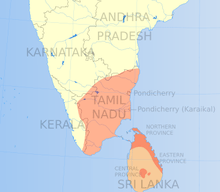

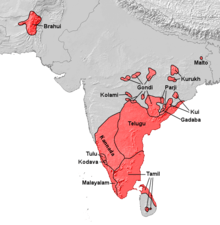

Tamilakam refers to the geographical region inhabited by the ancient Tamil people. Tamilakam covered today's Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Puducherry, Lakshadweep and southern parts of Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka. Traditional accounts and Tholkāppiyam referred these territories as a single cultural area, where Tamil was the natural language [note 1] and culture of all people.[note 2] The ancient Tamil country was divided into kingdoms. The best known among them were the Cheras, Cholas, Pandyans and Pallavas. During the Sangam period, Tamil culture began to spread outside Tamilakam.[3] Ancient Tamil settlements were also found in Sri Lanka (Sri Lankan Tamils) and the Maldives (Giravarus).

Etymology

| Part of a series on |

| Tamils |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Dravidian culture and history |

|---|

|

|

History

|

|

Regions

|

|

People |

| Portal:Dravidian civilizations |

| Part of a series on |

| History of Tamil Nadu |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Sri Lankan Tamils |

|---|

|

"Tamiḻakam" is a portmanteau of a word and suffix from the Tamil language, namely Tamiḻ and -akam. It can be roughly translated as the "homeland of the Tamils". According to Kamil Zvelebil, the term seems to be the most ancient term used to designate Tamil territory in the Indian subcontinent.[4]

The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, as well as Ptolemy's writings, mention the term "Limyrike" which corresponds to the Malabar Coast of south-western India. Based on a misinterpretation of the Roman map Tabula Peutingeriana and the possible phonetic connection between the words "Damir-" and "Tamil", some modern scholars have wrongly mentioned Limyrike as "Damirica" (or "Damirice"), considering it as a synonym of "Tamilakam". The "Damirice" mentioned in the Tabula Peutingeriana actually refers to an area between the Himalayas and the Ganges.[5]

Extent

The term "Tamilakam" appears to be the most ancient term used for designating the Tamil territory. The earliest sources to mention it include Purananuru 168.18 and Patiṟṟuppattu Patikam 2.5.[4][6] The Specific Preface (cirappuppayiram) of the more ancient text Tolkāppiyam mentions the terms tamil-kuru nal-lulakam ("the beautiful world [where] Tamil is spoken") and centamil ... nilam ("the territory ... of refined Tamil"). However, this preface, which is of uncertain date, is definitely a later addition to the original Tolkāppiyam.[7] According to the Tolkāppiyam preface, "the virtuous land in which Tamil is spoken as the mother tongue lies between the northern Venkata hill and the southern Kumari."[8]

The Silappadikaram (c. 5th-6th century CE) defines the Tamilakam as follows:[9]

| “ | The Tamil region extends from the hills of Vishnu [Tirupati] in the north to the oceans at the cape in the south. In this region of cool waters were the four great cities of: Madurai with its towers; Uraiyur which was famous; tumultuous Kanchi; and Puhar with the roaring waters [of the Kaveri and the ocean]. | ” |

While these ancient texts do not clearly define the eastern and western boundaries of the Tamilakam, scholars assume that these boundaries were the seas, which may explain their omission from the ancient definition.[10] The ancient Tamilakam thus included the present-day Kerala.[8] However, it excluded the present-day Tamil-inhabited territory in the Jaffna Peninsula of Sri Lanka.[11]

Subdivisions

Kingdoms

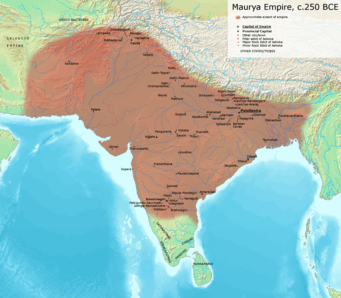

Approximately during the period between 350 BCE to 200 CE, Tamiḻakam was ruled by the three Tamil dynasties: the Chola dynasty, the Pandyan dynasty, Satyaputra dynasty and the Chera dynasty. There were also a few independent chieftains, the Velirs. The earliest datable references to the Tamil kingdoms are in inscriptions from the 3rd century BCE during the time of the Maurya Empire.

The Pandyan dynasty ruled parts of South India until the early 17th century. The heartland of the Pandyas was the fertile valley of the Vaigai River. They initially ruled their country from Korkai, a seaport on the southernmost tip of the Indian Peninsula, and in later times moved to Madurai. The Chola dynasty ruled from before the Sangam period (3rd century BCE) until the 13th century in central Tamil Nadu. The heartland of the Cholas was the fertile valley of the Kaveri. The Chera dynasty ruled from before the Sangam period (3rd century) until the 12th century over an area corresponding to modern-day western Tamil Nadu and Kerala.

The Vealirs (Vēḷir) were minor dynastic kings and aristocratic chieftains in Tamiḻakam in the early historic period of South India.[12][13]

Nadus of Tamilakam

Tamiḻakam was divided into political regions called Perunadu or "Great country", "nadu" means country.[14]

There were three important political regions which were Chera Nadu,[15][16][17] Chola Nadu and Pandya Nadu.[14] Along these three there were two more political regions of Athiyaman Nadu (Sathyaputha) and Thamirabharani Nadu (Then Paandi) which were later on absorbed into Chera resp. Pandya Nadu by 3rd century BCE. Thondai Nadu which was under Chola Nadu, later emerged as independent Pallava Nadu by 6th century CE.

Again Tamilakam were divided into 12 socio-geographical regions called Nadu or "country". Each of this Nadu had their own dialect of Tamil.[18]

- Thenpandi Nadu

- Panri Nadu

- Kuda Nadu

- Punal Nadu

- Puzhi Nadu

- Venad

- Aruva Nadu

- Kakkanad[19]

- Kuttanadu

- Aruva Vadathalai Nadu

- Sida Nadu

- Malai Nadu[20]

- Tulu Nadu[21]

Nadus outside Tamilakam

Some other Nadus were also mentioned in Tamil literatures which weren't part of Tamilakam, but the countries traded with Tamils in ancient times.

- Eela Nadu (Eelam)[22]

- Naga Nadu or Yazh Kuthanadu (Jaffna Peninsula)[23]

- Vanni Nadu (Vanni region)[23]

Other:

- Vengi Nadu[24]

- Chavaka Nadu (Java)[25]

- Kadara Nadu (Kedah)[25]

- Kalinga Nadu[25]

- Singhala Nadu [25]

- Vadugu Nadu [25]

- Kannada Nadu [25] (Land of Kannada people)

- Erumai Nadu [25]

- Telunka Nadu [25] (Land of Telugu people)

- Kolla Nadu [25]

- Vanka Nadu [25]

- Magadha Nadu [25]

- Kucala Nadu [25]

- Konkana Nadu [25]

- Kampocha Nadu (Cambodia) [25]

- Palantivu Nadu (Maldives) [25]

- Kupaka Nadu [25]

- Marattha Nadu [25]

- Vatuka Nadu [25]

- Tinmaitivu (Andaman and Nicobar Islands)[26]

Geocultural unity

Although the area covered by the term "Tamilakam" was divided among multiple kingdoms, its occurrence in the ancient literature implies that the region's inhabitants shared a cultural or ethnic identity, or at least regarded themselves as distinct from their neighbours.[27] The ancient Tamil inscriptions, ranging from 3rd or 2nd century BCE to 2nd or 3rd century CE, are also conisdered as linguistic evidence for distinguishing Tamilakam from the rest of South India.[28] The ancient non-Tamil inscriptions, such as those of the northern kings Ashoka and Kharavela, also allude to the distinct identity of the region. For example, Ashoka's inscriptions refer to the independent states lying beyond the southern boundary of his kingdom, and Kharavdela's Hathigumpha inscription refers to the destruction of a "confederacy of Tamil powers".[29]

However, the archaeological evidence does not support the existence of "Tamilakam" as a distinct cultural region: the material culture and habitations discovered in present-day Tamil Nadu and Kerala are also found elsewhere in peninsular India and Sri Lanka.[30]

Cultural influence

With the advent of the early historical period in South India[3] and the ascent of the three Tamil kingdoms in South India in the 3rd century BCE,[3] Tamil culture began to spread outside Tamiḻakam. In the 3rd century BCE, more Tamil settlers arrived in Sri Lanka.[31] The Annaicoddai seal, dated to the 3rd century BCE, contains a bilingual inscription in Tamil-Brahmi.Though Tamils have been living in Sri Lanka since the Ancient era at least[32][33] with universally accepted dates of at least the 10th century BCE showing signs of Tamil civilization in Sri Lanka[34][35][note 3] Excavations in the area of Tissamaharama in southern Sri Lanka have unearthed locally issued coins produced between the second century BCE and the second century CE, some of which carry local Tamil personal names written in early Tamil letters,[36] which suggest that local Tamil merchants were present and actively involved in trade along the southern coast of Sri Lanka by the late classical period.[37] Around 237 BCE, "two adventurers from southern India"[38] established the first Tamil rule at Sri Lanka. In 145 BCE Elara, a Chola general[38] or prince known as Ellāḷaṉ[39] took over the throne at Anuradhapura and ruled for forty-four years.[38] Dutugamunu, a Sinhalese, started a war against him, defeated him, and took over the throne.[38][40] Tamil Kings have been dated in Sri Lanka to at least the 3rd century BCE [41][42] with great accuracy and older ones were being excavated throguh archaeological means before the Civil War lead to widespread destruction of historically Tamil Lands in Sri Lanka.

Religion

Jains, Buddhists and Hindus have coexisted in Tamil country for at least as early as the second century BCE.[43]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Thapar mentions the existence of a common language of the Dravidian group: "Ashoka in his inscription refers to the peoples of South India as the Cholas, Cheras, Pandyas and Satiyaputras - the crucible of the culture of Tamilakam - called thus from the predominant language of the Dravidian group at the time, Tamil".[1]

- ↑ See, for example, Kanakasabhai.[2]

- ↑ An archaeological team led by K.Indrapala of the University of Jaffna excavated a megalithic burial complex at Anaikoddai in Jaffna District, Sri Lanka. In one of the burials, a metal seal was found assigned by the excavators to c. the 3rd century BCE.[35]

References

- ↑ Thapar 2004, p. 229.

- ↑ Kanakasabhai 1904, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 Singh 2009, p. 384.

- 1 2 Zvelebil 1992, p. xi.

- ↑ Lionel Casson (2012). The Periplus Maris Erythraei: Text with Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. Princeton University Press. pp. 213–214. ISBN 1-4008-4320-0.

- ↑ Peter Schalk; A. Veluppillai; Irāmaccantiran̲ Nākacāmi (2002). Buddhism among Tamils in pre-colonial Tamilakam and Īlam. Almqvist & Wiksell. p. 56. ISBN 978-91-554-5357-2.

- ↑ Zvelebil 1992, p. x.

- 1 2 Shu Hikosaka (1989). Buddhism in Tamilnadu: A New Perspective. Institute of Asian Studies. p. 3.

- ↑ Kanakalatha Mukund (2015). The World of the Tamil Merchant: Pioneers of International Trade. Penguin Books. p. 27. ISBN 978-81-8475-612-8.

- ↑ P. C. Alexander (1949). Buddhism in Kerala. Annamalai University. p. 2.

- ↑ K. P. K. Pillay (1963). South India and Ceylon. University of Madras. p. 40.

- ↑ Mahadevan, Iravatham (2009). "Meluhha and Agastya : Alpha and Omega of the Indus Script" (PDF). Chennai, India. p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2011.

The Ventar - Velir - Vellalar groups constituted the ruling and land-owning classes in the Tamil country since the beginning of recorded history

- ↑ Fairservis, Walter Ashlin (1992) [1921]. The Harappan civilization and its writing. A model for the decipherment of the Indus Script. Oxford & IBH. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-81-204-0491-5.

- 1 2 Iyengar, P. T. Srinivasa (1929-01-01). History of the Tamils from the Earliest Times to 600 A.D. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120601451.

- ↑ Ponnumuthan, Sylvister (1996). The Spirituality of Basic Ecclesial Communities in the Socio-Religious Context of Trivandrum/Kerala, India. Gregorian&Biblical BookShop.

- ↑ S. Soundararajan (1991). Ancient Tamil country: its social and economic structure. Navrang. p. 30.

- ↑ K. Lakshminarasimhan; Muthuswamy Hariharan; Sharada Gopalam (1991). Madhura kala: silver jubilee commemoration volume. CBH Publications. p. 141.

- ↑ Kanakasabhai 1904.

- ↑ History of the Tamils from the Earliest Times to 600 A.D., P. T. Srinivasa Iyengar, Asian Educational Services 1929, p.151

- ↑ Sri Varadarajaswami Temple, Kanchi: A Study of Its History, Art and Architecture, K.V. Raman Abhinav Publications, 01.06.2003, p.17

- ↑ A handbook of Kerala Band 1 (2000), T. Madhava Menon, International School of Dravidian Linguistics, p.98

- ↑ Census of India, 1961: India, India. Office of the Registrar General Manager of Publications.

- 1 2 The Sri Lanka Reader: History, Culture, Politics, By John Holt, Duke University Press, 13 April 2011 see (Tamil Nadus in Rajarata p.85.)

- ↑ Ancient India: Collected Essays on the Literary and Political History of Southern India, By Sakkottai Krishnaswami Aiyangar, Asian Educational Services 1911, p.121.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics: IJDL. Department of Linguistics, University of Kerala. 2001-01-01.

- ↑ Government of India (1908). "The Andaman and Nicobar Islands: Local Gazetteer". Superintendent of Government Printing, Calcutta.

... In the great Tanjore inscription of 1050 AD, the Andamans are mentioned under a translated name along with the Nicobars, as Nakkavaram or land of the naked people.

- ↑ Abraham 2003, p. 211.

- ↑ Abraham 2003, pp. 211-212.

- ↑ Abraham 2003, p. 212.

- ↑ Abraham 2003, p. 208,217.

- ↑ Wenzlhuemer 2008, p. 19-20.

- ↑ de Silva 2005, p. 129.

- ↑ Indrapala 2007, p. 91.

- ↑ Subramanian, T. S. (27 January 2006). "Reading the past in a more inclusive way:Interview with Dr. Sudharshan Seneviratne". Frontline. 23 (1). Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- 1 2 Mahadevan 2002.

- ↑ Mahadevan, I. "Ancient Tamil coins from Sri Lanka", pp. 152–154

- ↑ Bopearachchi, O. "Ancient Sri Lanka and Tamil Nadu", pp. 546–549

- 1 2 3 4 Reddy 2003, p. 45.

- ↑ "The Five Kings - Mahasiva, Suratissa, Elara, Asela, Sena, and Guttika". mahavamsa.org. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ↑ Deegalle 2006, p. 30.

- ↑ Indrapala 2007, p. 324.

- ↑ Mahadevan, Iravatham (24 June 2010). "An epigraphic perspective on the antiquity of Tamil". The Hindu.

- ↑ John E. Cort 1998, p. 187.

Sources

Printed sources

- Abraham, Shinu (2003). "Chera, Chola, Pandya: using archaeological evidence to identify the Tamil kingdoms of early historic South India". Asian Perspectives. 42 (2): 207. doi:10.1353/asi.2003.0031

- John E. Cort, ed. (1998), Open Boundaries: Jain Communities and Cultures in Indian History, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-3785-X

- Aiyangar, Muttusvami Srinivasa (1986). "Tamil studies: essays on the history of the Tamil people, language, religion, and literature". Asian Educational Services. Retrieved 24 April 2012

- Aiyaṅgār, Sākkoṭṭai Krishṇaswāmi (1994). Evolution of Hindu Administrative Institutions in South India. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-0966-2

- Deegalle, Mahinda (2006). "Buddhism, Conflict and Violence in Modern Sri Lanka". Routledge

- Hanumanthan, Krishnaswamy Ranaganathan (1979). "Untouchability: a historical study upto 1500 A.D. : with special reference to Tamil Nadu". Koodal Publishers

- Holt, John (2011). "The Sri Lanka Reader: History, Culture, Politics". Duke University Press

- Indrapala, K. (1969). "Early Tamil settlements in Ceylon". Journal of the Ceylon branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1969, XIII:54

- Kanakasabhai, V (1904). The Tamils Eighteen Hundred Years Ago. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 8120601505

- Krishnan, Shankara (1999). Postcolonial Insecurities: India, Sri Lanka, and the Question of Nationhood. University of Minnesota Press. p. 172. ISBN 0-8166-3330-4

- Mahadevan, Iravatham (2002). "Aryan or Dravidian or Neither? – A Study of Recent Attempts to Decipher the Indus Script (1995–2000)". Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies. 8 (1). Archived from the original on 23 July 2007

- Manogaran, Chelvadurai (1987). "Ethnic Conflict and Reconciliation in Sri Lanka". University of Hawaii Press

- Rajayyan, K. (2005). "Tamil Nadu, a real history". Ratna Publications

- Ramaswamy, Sumathi (1997). Passions of the Tongue: Language Devotion in Tamil India, 1891-1970. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20805-6

- Ramaswamy, Vijaya (2007). Historical Dictionary of the Tamils. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5379-9

- Reddy, L.R. (2003). "Sri Lanka: Past and Present". APH Publishing

- Singh, Upinder (2009). "A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century". Pearson Education India

- Smith, Vincent A. (1999). The Early History of India. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-7156-618-1

- Thapar, Romila (2004). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520242258

- Wenzlhuemer, Roalnd (2008). "From Coffee to Tea Cultivation in Ceylon, 1880-1900: An Economic and Social History". BRILL

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1973). "The smile of Murugan on Tamil literature of South India". Leiden: Brill

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1992). "Companion studies to the history of Tamil literature". BRILL