Central African Republic Civil War (2012–present)

| Central African Republic Civil War (2012–Present) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

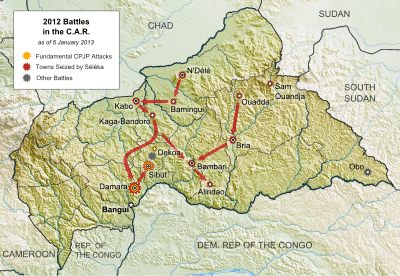

Map of battles in the Central African Republic | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

MISCA (2013–2014)

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

|

EUFOR RCA: MICOPAX: |

| ||||||

| Strength | ||||||||

|

3,000 (Séléka claim)[5] 1,000–2,000 (Other estimates)[6] |

ECCAS: 3,500+ peacekeepers[5][8] African Union: 6,000[8] | 50,000[11]-72,000[12] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

| 500+ rebel casualties (Bangui only, South African claim) |

1 policeman killed | 53 | ||||||

The Central African Republic conflict is a civil war in the Central African Republic (CAR) involving the government, rebels from the Séléka coalition and the Anti-balaka militias.[19]

In the Central African Republic Bush War, the government of President François Bozizé fought with rebels until a peace agreement in 2007. The current conflict arose when a new coalition of varied rebel groups, known as Séléka,[20] accused the government of failing to abide by the peace agreements[19] and captured many towns at the end of 2012. The capital was seized by the rebels in March 2013,[21] Bozizé fled the country,[22] and the rebel leader Michel Djotodia declared himself president.[23] Renewed fighting began between Séléka and militias called anti-balaka.[24] In September 2013, President Djotodia disbanded the Seleka coalition which had lost its unity after taking power and in January 2014, Djotodia resigned[25][26] and was replaced by Catherine Samba-Panza,[27] but the conflict continued.[28] In July 2014, Ex-Séléka factions and anti-balaka representatives signed a ceasefire agreement in Brazzaville.[29] By the end of 2014, the country was de facto partitioned with the anti-Balaka in the south and west, with most of its Muslims evacuated, and ex-Seleka in the north and east.[30]

Much of the tension is over religious identity between Muslim Seleka fighters and Christian Anti-balaka as well as over historical antagonism between agriculturalists, who largely comprise Anti-balaka and nomadic groups, who largely comprise Seleka fighters and ethnic differences among Ex-Seleka factions.[31] More than 1.1 million people have fled their homes in a country of about 5 million people, the highest ever recorded in the country.[32]

Background

The peacekeeping force Multinational Force in the Central African Republic (FOMUC) was formed in October 2002 by the regional economic community, Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (CEMAC).[33][34]

After François Bozizé seized power in 2003, the Central African Republic Bush War (2004–2007) began with the rebellion by the Union of Democratic Forces for Unity (UFDR) in North-Eastern CAR, led by Michel Djotodia.[35][36] During this conflict, the UFDR rebel forces also fought with several other rebel groups including the Groupe d'action patriotique pour la libération de Centrafrique (GAPLC), the Convention of Patriots for Justice and Peace (CPJP), the People's Army for the Restoration of Democracy (APRD), the Movement of Central African Liberators for Justice (MLCJ), and the Front démocratique Centrafricain (FDC).[37] Tens of thousands of people were displaced by the unrest, which continued until 2007, with rebel forces seizing several cities during the conflict.

On 13 April 2007, a peace agreement between the government and the UFDR was signed in Birao. The agreement provided for an amnesty for the UFDR, its recognition as a political party, and the integration of its fighters into the army.[38][39] Further negotiations resulted in an Libreville Global Peace Accord agreement in 2008 for reconciliation, a unity government, and local elections in 2009 and parliamentary and presidential elections in 2010.[40] The new unity government that resulted was formed in January 2009.[41] On 12 July 2008, with the waning of the Central African Republic Bush War, the larger overlapping regional economic community to CEMAC called the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) replaced FOMUC, whose mandate was largely restricted to security, with the Central African Peacebuilding Mission (MICOPAX), who had a broader peace building mandate.[33]

Rebel groups alleged that Bozizé had not followed the terms of the 2007 agreement and that there continued to be political abuses, especially in the northern part of the country, such as "torture and illegal executions".[42]

Course of the conflict

Toppling Bozizé (2012-2013)

Formation of Seleka

In August 2012 a peace agreement was signed between the government and the CPJP.[43] On August 20, 2012, an agreement was signed between a dissident faction of the CPJP, led by Colonel Hassan Al Habib calling itself "Fundamental CPJP". and the Patriotic Convention for Saving the Country (CPSK).[44] Al Habib announced that, in protest of the peace agreement, the Fundamental CPJP was launching an offensive dubbed "Operation Charles Massi", in memory of the CPJP founder who was allegedly tortured and murdered by the government and that his group intended to overthrow Bozizé.[45][46] In September, fundamental CPJ, using the French name alliance CPSK-CPJP took responsibility for attacks on the towns of Sibut, Damara and Dekoa, killing two members of the army.[47][48] It claimed that it had killed two additional members of the Central African Armed Forces (FACA) in Damara, capturing military and civilian vehicles, weapons including rockets, and communications equipment, and launched unsuccessful assault on a fourth town, Grimari and promised more operations in future.[49] Mahamath Isseine Abdoulaye, president of the pro-government CPJP faction, countered that the CPJP was committed to the peace agreement and the attacks were the work of Chadian rebels, saying this group of "thieves" would never be able to march on Bangui. Al Habib was killed by the FACA on 19 September in Daya, a town north of Dekoa.[50]

In November 2012, in Obo, FACA soldiers were injured in an attack attributed to Chadian Popular Front for Recovery rebels.[51] On 10 December 2012, the rebels seized the towns of N'Délé, Sam Ouandja and Ouadda, as well as weapons left by fleeing soldiers.[52][53][54] On 15 December, rebel forces took Bamingui, and three days later they advanced to Bria, moving closer to Bangui. The alliance for the first time used the name "Seleka" (meaning "union" in the Sango language) with a press release calling itself "Séléka CPSK-CPJP-UFDR" thus including the Union of Democratic Forces for Unity (UFDR).[55] The Séléka claim they are fighting because of a lack of progress after a peace deal ended the Bush War.[56] Following an appeal for help from Central African President François Bozizé, the President of Chad, Idriss Déby, pledged to send 2000 troops to help quell the rebellion.[57][58] The first Chadian troops arrived on 18 December to reinforce the CAR contingent in Kaga Bandoro, in preparation for a counter-attack on N'Délé. Séléka forces took Kabo on 19 December, a major hub for transport between Chad and CAR, located west and north of the areas previously taken by the rebels.[59] On 18 December 2012, the Chadian group Popular Front for Recovery (FPR)[60] announced their allegiance to the Séléka coalition. On 20 December 2012, a rebel group based in northern CAR, the Democratic Front of the Central African People (FDPC) joined the Seleka coalition.[61] Four days later the rebel coalition took over Bambari, the country's third largest town,[62] followed by Kaga-Bandoro on 25 December.[63] Rebel forces reached Damara, bypassing the town of Sibut where around 150 Chadian troops are stationed together with CAR troops that withdrew from Kaga-Bandoro.

On 26 December, hundreds of protesters surrounded the French embassy accusing the former colonial power of failing to help the army.[64] Josué Binoua, the CAR's minister for territorial administration, requested that France intervenes in case the rebels, now only 75 km (47 mi) away, manage to reach the capital Bangui.[65] On 27 December, Bozizé asked the international community for assistance. French President François Hollande rejected the appeal, saying that French troops would only be used to protect French nationals in the CAR, and not to defend Bozizé's government. Reports indicated that the U.S. military was preparing plans to evacuate "several hundred" American citizens, as well as other nationals.[66][67] General Jean-Felix Akaga, commander of the Economic Community of Central African States' (ECCAS) Multinational Force of Central Africa, said the capital was "fully secured" by the troops from its MICOPAX peacekeeping mission, adding that reinforcements should arrive soon. However, military sources in Gabon and Cameroon denied the report, claiming no decision had been taken regarding the crisis.[68]

Government soldiers launched a counterattack against rebel forces in Bambari on 28 December, leading to heavy clashes, according to a government official. Several witnesses over 60 km (37 mi) away said they could hear detonations and heavy weapons fire for a number of hours. Later, both a rebel leader and a military source confirmed the military attack was repelled and the town remained under rebel control. At least one rebel fighter was killed and three were wounded in the clashes, the military's casualties were unknown.[69]

Meanwhile, the foreign ministers in the ECCAS announced that more troops from the Multinational Force for Central Africa (FOMAC) would be sent to the country to support the 560 members of the MICOPAX mission already present. The announcement was done by Chad's Foreign Minister Moussa Faki after a meeting in the Gabonese capital Libreville. At the same time, ECCAS deputy secretary general Guy-Pierre Garcia confirmed that the rebels and the CAR government had agreed to unconditional talks, with the goal to get to negotiations by 10 January at the latest. In Bangui, the U.S. Air Force evacuated around 40 people from the country, including the American ambassador. The International Committee of the Red Cross also evacuated eight of its foreign workers, though local volunteers and 14 other foreigners remained to help the growing number of displaced people.[70]

Rebel forces took over the town of Sibut without firing a shot on 29 December, as at least 60 vehicles with CAR and Chadian troops retreated to Damara, the last city standing between Séléka and the capital. In Bangui, the government ordered a 7 pm to 5 am curfew and banned the use of motorcycle taxis, fearing they could be used by rebels to infiltrate the city. Residents reported many shop-owners had hired groups of armed men to guard their property in anticipation of possible looting, as thousands were leaving the city in overloaded cars and boats. The French military contingent rose to 400 with the deployment of 150 additional paratroopers sent from Gabon to Bangui M'Poko International Airport. French Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault again stressed that the troops were only present to "protect French and European nationals" and not deal with the rebels.[71][72]

Truce discussions and foreign troops

On 30 December, President Bozizé agreed to a possible national unity government with members of the Séléka coalition, after meeting with African Union chairperson Thomas Yayi Boni. He added that the CAR government was ready to begin peace talks "without condition and without delay".[5] By 1 January reinforcements from FOMAC began to arrive in Damara to support the 400 Chadian troops already stationed there as part of the MICOPAX mission. With rebels closing in on the capital Bangui, a total of 360 soldiers were sent to boost the defenses of Damara – Angola, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 120 each from Gabon, Republic of the Congo and Cameroon, with a Gabonese general in command of the force.[73] In the capital itself, deadly clashes erupted after police killed a young Muslim man suspected of links to Séléka. According to news reports, the man was arrested overnight and was shot when he tried to escape. Shortly after that clashes began in Bangui's PK5 neighborhood, killing one police officer. Meanwhile, in a new development, the US State Department voiced its concern over the "arrests and disappearances of hundreds of individuals who are members of ethnic groups with ties to the Séléka rebel alliance".

On 2 January 2013, a presidential decree read on state radio announced that President Bozizé was the new head of the defense ministry, taking over from his son, Jean Francis Bozize. In addition, army chief Guillaume Lapo was dismissed due to failure of the CAR military to stop the rebel offensive in December.[74] Meanwhile, rebel spokesman Col. Djouma Narkoyo confirmed that Séléka had stopped their advance and will enter peace talks due to start in Libreville on 8 January, on the precondition that government forces stop arresting members of the Gula tribe. The rebel coalition confirmed it would demand the immediate departure of president Bozize, who had pledged to see out his term until its end in 2016. Jean-Félix Akaga, the Gabonese general in charge of the MICOPAX force sent by the ECCAS, declared that Damara represented a "red line that the rebels cannot cross", and that doing so would be "a declaration of war" against the 10 members of the regional bloc. It was also announced that Angola had contributed to the 760 troops stationed in the CAR, while France had further boosted its military presence in the country to 600 troops, sent to protect French nationals in case it is required.[73]

On 6 January, South African President Jacob Zuma announced the deployment of 400 troops to the CAR to assist the forces already present there. Rebel forces secured two small towns near Bambari as peace talks were scheduled to begin in two days.[75]

Elisabeth Blanche Olofio, a radio journalist for Radio Bé-Oko, was killed by the Séléka coalition, who attacked the station in Bambari and another Radio Kaga in Kaga Bandoro on 7 January 2013.[76][77][78] Radio Bé-Oko is part of a larger network of apolitical radio stations operating in the Central African Republic, known as L'Association des Radios Communautaires de Centrafrique.[79][80] The international press freedom organization Reporters Without Borders said it was concerned that the rebel attacks were taking their toll on the ability of radio stations to operate in the CAR.[81]

Ceasefire agreement

On 11 January 2013, a ceasefire agreement was signed in Libreville, Gabon.[82] On 13 January, Bozizé signed a decree that removed Prime Minister Faustin-Archange Touadéra from power, as part of the agreement with the rebel coalition.[83] The rebels dropped their demand for President François Bozizé to resign, but he had to appoint a new prime minister from the opposition by 18 January 2013.[42] On 17 January, Nicolas Tiangaye was appointed Prime Minister.[84]

The terms of the agreement also included that National Assembly of the Central African Republic be dissolved within a week with a year-long coalition government formed in its place and a new legislative election be held within 12 months (with the possibility of postponement).[85] In addition the temporary coalition government had to implement judicial reforms, amalgamate the rebel troops with the Bozizé government's troops in order to establish a new national military, set up the new legislative elections, as well as introduce other social and economic reforms.[85] Furthermore, Bozizé's government was required to free all political prisoners imprisoned during the conflict, and foreign troops must return to their countries of origin.[42] Under the agreement, Séléka rebels were not required to give up the cities they have taken or were then occupying, allegedly as a way to ensure that the Bozizé government would not renege on the agreement.[42]

Bozizé, who was to remain President until new presidential elections in 2016, said the agreement was "... a victory for peace because from now on Central Africans in conflict zones will be finally freed from their suffering."[86]

On 23 January 2013, the ceasefire was broken, with the government blaming Séléka[87] and Séléka blaming the government for allegedly failing to honor the terms of the power-sharing agreement.[88] By 21 March, the rebels had advanced to Bouca, 300 km from the capital Bangui.[88] On 22 March, the fighting reached the town of Damara, 75 km from the capital,[89] with conflicting reports as to which side was in control of the town.[90] Rebels overtook the checkpoint at Damara and advanced toward Bangui, but were stopped with an aerial assault from an attack helicopter.[91]

Fall of Bangui

On 18 March 2013, the rebels kept their five ministers from returning to Bangui following talks about the peace process in the town of Sibut. The rebels demanded the release of political prisoners and the integration of rebel forces into the national army. Séléka also wanted South African soldiers who had been on assignment in Central African Republic to leave the country. Séléka threatened to take up arms again if the demands were not met, giving the government a deadline of 72 hours. Before that the rebels seized control of two towns in the country's southeast, Gambo and Bangassou.[92]

On 22 March 2013, the rebels renewed their offensive. They took control of the towns of Damara and Bossangoa. After Damara fell, fears were widespread in Bangui that the capital too would soon fall, and a sense of panic pervaded the city, with shops and schools closed.[93] Government forces briefly halted the rebel advance by firing on the rebel columns with an attack helicopter,[91] but by 23 March, the rebels shot down the helicopter,[94] entered Bangui, and were "heading for the Presidential Palace," according to Séléka spokesman Nelson Ndjadder.[95] Rebels reportedly managed to push out government soldiers in the neighbourhood surrounding Bozizé's private residence, though the government maintained that Bozizé remained in the Presidential Palace in the centre of the city.[96]

Fighting died down during the night as power and water supplies were cut off. Rebels held the northern suburbs whilst the government retained control of the city centre. A government spokesman insisted that Bozizé remained in power and that the capital was still under government control.[97]

On 24 March, rebels reached the presidential palace in the centre of the capital, where heavy gunfire erupted.[98] The presidential palace and the rest of the capital soon fell to rebel forces and Bozizé fled to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[22][99] "A presidential adviser said he had crossed the river into DRC on Sunday morning [24 March] as rebel forces headed for the presidential palace."[100] He was later said to have sought temporary refuge in Cameroon, according to that country's government.[101] The United Nations refugee agency received a request from the Congolese government to help move 25 members of Bozizé's family from the border town of Zongo.[102] A spokesman for the president stated that "The rebels control the town; I hope there will not be any reprisals."[102]

Rebel leaders claimed to have told their men to refrain from any theft or reprisals but residents in the capital are said to have engaged in widespread looting. Water and power have been cut to the city.[99] Rebel fighters directed looters towards the houses of army officers but fired their rifles in the air to protect the homes of ordinary citizens.[102]

Thirteen South African soldiers were killed and twenty-seven wounded and one was missing after their base on the outskirts of Bangui was attacked by an armed rebel group of 3,000 rebels, starting an intense firefight between the rebels and the base's 400 South African National Defence Force soldiers that lasted an unspecified amount of time.[103] General Solly Shoke, the Chief of the South African National Defence Force, stated at a press conference on 24 March 2013 that the SANDF soldiers had 'inflicted heavy losses' on the rebels, retained control of their base and forced the rebels into a ceasefire. Shoke also claimed that there are no plans as yet for the South African troops to leave the Central African Republic,[104] although by April 2, only 20 of the original 200 SANDF troops stationed in the CAR remained in the country.[105]

According to the SANDF, its force of about 200 soldiers faced 3,000 experienced armed rebels, by the time the rebels proposed a cease-fire they had lost 500 men to the 13 killed and 27 wounded of the SANDF.[106][107] Séléka general Hassan Ahmat claimed his men killed "at least 36 South African soldiers and captured 46", and lashed out against the SANDF with an accusation of acting as "mercenaries" for Bozizé.[108]

Several peacekeepers from the Central African regional force, including three Chadians, were also killed on 24 March, when a helicopter operated by Bozize's forces attacked them, Chad's presidency said in a statement.[102]

A company of French troops secure Bangui M'Poko International Airport, while a diplomatic source confirmed that Paris had asked for an emergency UN Security Council meeting to discuss the rebel advance.[109] France sent 350 soldiers to ensure the security of its citizens, a senior official told AFP, bringing the total number of French troops in CAR to nearly 600, though a spokesman stated that there are no plans to send further troops to the country.[99][110] On 26 March French defence ministry said that French troops guarding the airport had accidentally killed two Indian citizens. The soldiers shot at three vehicles approaching the airport after firing warning shots and themselves coming under fire, the statement said. Two Indian nationals and a number of Cameroonians were wounded in the attack.[111]

On 25 March 2013, Séléka leader Michel Djotodia, who served after the January agreement as First Deputy Prime Minister for National Defense, declared himself President. He was also the first Muslim to ever hold office in CAR.[112] Djotodia said that there would be a three-year transitional period and that Nicolas Tiangaye would continue to serve as Prime Minister.[113] Djotodia promptly suspended the constitution and dissolved the government, as well as the National Assembly.[114] He then reappointed Tiangaye as Prime Minister on 27 March 2013.[115][116]

Séléka rule and fall of Djotodia (2013-2014)

Following the rebel victory in the capital, small pockets of resistance remained and fought against the new regime. The resistance consisted mostly of youths that received weapons from the former government. Over 100 soldiers loyal to the former government were holed up at a base 60 km from the capital, refusing to surrender their weapons, although talks were underway to allow them to return to their homes. By 27 March, electric power was slowly being restored across the capital and the overall security situation was beginning to improve.[117]

Top military and police officers met with Djotodia and recognized him as President on 28 March 2013, in what was viewed as "a form of surrender".[118]

On 30 March, officials from the Red Cross announced that they had found 78 bodies in the capital Bangui since rebels seized it a week earlier. It was unclear if the casualties were civilians or whether they belonged to one of the factions in the conflict.[119]

A new government headed by Tiangaye, with 34 members, was appointed on 31 March 2013; Djotodia retained the defense portfolio. There were nine members of Séléka in the government, along with eight representatives of the parties that had opposed Bozizé, while only one member of the government was associated with Bozizé.[120][121] 16 positions were given to representatives of civil society. The former opposition parties were unhappy with the composition of the government; on 1 April, they declared that they would boycott the government to protest its domination by Séléka. They argued that the 16 positions given to representatives of civil society were in fact "handed over to Séléka allies disguised as civil society activists".[122]

On 3 April 2013, African leaders meeting in Chad declared that they did not recognize Djotodia as President; instead, they proposed the formation of an inclusive transitional council and the holding of new elections in 18 months, rather than three years as envisioned by Djotodia. Speaking on 4 April, Information Minister Christophe Gazam Betty said that Djotodia had accepted the proposals of the African leaders; however, he suggested that Djotodia could remain in office if he were elected to head the transitional council.[123] Djotodia accordingly signed a decree on 6 April for the formation of a transitional council that would act as a transitional parliament. The council was tasked with electing an interim president to serve during an 18-month transitional period leading to new elections.[124]

The transitional council, composed of 105 members, met for the first time on 13 April 2013 and immediately elected Djotodia as interim President; there were no other candidates.[125] A few days later, regional leaders publicly accepted Djotodia's transitional leadership, but, in a symbolic show of disapproval, stated that he would "not be called President of the Republic, but Head of State of the Transition". According to the plans for the transition, Djotodia would not stand as a candidate for President in the election that would conclude the transition.[126][127]

On 13 September 2013, Djotodia formally disbands Seleka, which he had lost effective control of once the coalition had taken power. This had little actual effect in stopping abuses by the militia soldiers who were now referred to as Ex-seleka.[128] Self-defense militias called Antibalaka previously formed to fight crime on a local level, had organized into militias against abuses by Seleka soldiers. On 5 December 2013, called "A Day That Will Define Central African Republic", the antibalaka militias coordinated an attack on Bangui against its Muslim population, killing more than 1,000 civilians, in an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow Djotodia.[129]

On 14 May CAR's PM Nicolas Tiangaye requested a UN peacekeeping force from the UN Security Council and on 31 May former President Bozizé was indicted for crimes against humanity and incitement of genocide.[130] On the same day as the December 5th attacks, the UN Security Council authorized the transfer of MICOPAX to the African Union led peacekeeping mission the International Support Mission in the Central African Republic (MISCA or AFISM-CAR) with troop numbers increasing from 2,000 to 6,000[34][131] as well as for the French peacekeeping mission called Operation Sangaris.[128]

Michel Djotodia and Prime Minister Nicolas Tiangaye resigned on 10 January 2014.[132] Despite the resignation of Djotodia, conflict still continued.[133] On 19 January, Save the Children reported that in Bouar gunmen fired a rocket-propelled grenade in an attempt to halt a convoy of Muslim refugees trying to flee the violence. The gunmen then attacked them with firearms, machetes and clubs resulting in 22 deaths.[134] The UN had also warned of a possibility of genocide.[135]

The National Transitional Council elected the new interim president of the Central Africa Republic after Nguendet became the acting chief of state. Nguendet, being the president of the provisional parliament and viewed as being close to Djotodia, did not run for the election under diplomatic pressure.[136] The parliament validated the candidatures of 8 people out of 24.[137]

On 20 January 2014, Catherine Samba-Panza, the mayor of Bangui, was elected as the interim president in the second round voting.[27] The election of Samba-Panza was welcomed by Ban Ki-moon, the UN Secretary-General.[138] Samba-Panza was viewed as having been neutral and away from clan clashes. Her arrival to the presidency was generally accepted by both the ex-Séléka and the anti-balaka sides. Following the election, Samba-Panza made a speech in the parliament appealing to the ex-Séléka and the anti-balaka for putting down their weapons.[139]

Ex-Séléka and Anti-Balaka fighting (2014 - present)

On 27 January, Séléka leaders left Bangui under the escort of Chadian peacekeepers.[140] The aftermath of Djotodia's presidency was said to be without law, a functioning police and courts.[141] In the days after the election of the interim president, anti-Muslim pogroms and looting of Muslim neighborhoods continued in Bangui,[142][143][144] including the lynching of the Muslim former Health Minister Dr. Joseph Kalite[145][146] by Christian self-defence groups.[147] Accounts state of lynch mobs, including that of uniformed soldiers, stoning or hacking Muslims then dismembering and burning their bodies in the streets.[148]

The European Union decided to set up its first military operations in six years when foreign ministers approved the sending of up to 1,000 soldiers to the country by the end of February, to be based around Bangui. Estonia promised to send soldiers, while Lithuania, Slovenia, Finland, Belgium, Poland and Sweden were considering sending troops; Germany, Italy and Great Britain announced that they would not send soldiers.[149] The UN Security Council unanimously voted to approve sending European Union troops and to give them a mandate to use force, as well as threatening sanctions against those responsible for the violence. The E.U. had pledged 500 troops to aid African and French troops already in the country. Specifically the resolution allowed for the use of "all necessary measures" to protect civilians.[150]

As UN Secretary-General Ban-ki Moon warned of a de facto partition of the country into Muslim and Christian areas as a result of the sectarian fighting,[151] He also called the conflict an "urgent test" for the UN and the region's states.[152] Amnesty International blamed the anti-balaka militia of causing a "Muslim exodus of historic proportions."[153] Samba-Panza suggested poverty and a failure of governance was the cause of the conflict.[154] Some Muslims of the country were also weary of the French presence in MISCA, with the French accused of not doing enough to stop attacks by Christian militias. One of the cited reasons for the difficulty in stopping attacks by anti-balaka militias was the mob nature of these attacks.[155]

On 4 February 2014, a local priest said 75 people were killed in the town of Boda, in Lobaye province.[156]

On 15 February, France announced that it would send an additional 400 troops to the country. French President Francois Hollande's office called for "increased solidarity" with the CAR and for the United Nations Security Council to accelerate the deployment of peacekeeping troops to the CAR.[157] Moon then also called for the rapid deployment of 3,000 additional international peacekeepers.[158] Because of increasing violence, on 10 April 2014, the UN Security Council transferred MISCA to a UN peacekeeping operation called the Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) with 10,000 troops, to be deployed in September that year.[131] MINUSCA drew figurative "red lines" on the roads to keep the peace among rival militias.[7]

In the northeast of the country, the former Séléka rebels were reported to be regrouping amid fears of continued reprisal attacks against Muslims in Christian areas and vice versa. In the aforementioned part of the country a new armed movement named Justice et Redressement was reported to be operating in and around Paoua and Boguila. Though its goals were unknown, there were threats that the weakening writ of the state could evolve into third-party armed groups form to pursue their own agendas, while even violent Islamist groups could appear.

In the southwest, anti-balaka militants attacked Guen in early February resulting in the deaths of 60 people, according to Father Rigobert Dolongo, who also said that he had helped bury the bodies of the dead, at least 27 of whom died on the first day of the attack and 43 others the next day. As a result, hundreds of Muslim refugees sought shelter at a church in Carnot.[159] In the end of the month, French President Francois Hollande made another trip to the country after a security conference in Nigeria. He met the French MISCA contingent, Samba-Panza and other unnamed religious leaders.[160] UN humanitarian coordinator Abdou Dieng said that only about US$100 million, or one-fifth of that which was pledged, had arrived in the country to fight a food shortage. He also warned of a food crisis that was thus looming.[161] On a visit to Angola at the behest of President Jose Eduardo dos Santos, who was praised for his "special involvement" in the country, Samba-Panza said: "We do not have a situation of genocide, but the situation prevailing is really worrying, so we are fighting to take security to all population, no matter their religions." She also suggested that while the situation was "worrying" it was "under control."[162] By mid-March, the UNSC had authorised a probe into possible genocide, which in turn followed International Criminal Court Chief Prosecutor Fatou BEnsouda initiating a preliminary investigation into the "extreme brutality" and whether it falls into the court's remit. The UNSC mandate probe would be led by Cameroonian lawyer Bernard Acho Muna, who was the deputy chief prosecutor for the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, former Mexican Secretary of Foreign Affairs Jorge Castaneda and Mauritanian lawyer Fatimata M'Baye.[163] On 13 March, a group of religious leaders — Imam Omar Layama, Reverend Nicolas Gbangou and Archbishop Dieudonne Nzapalainga — asked the Ban-ki Moon to redouble efforts to bring peace to the country.[164]

Flavien Mulume, the acting commander of the Congolese contingent of MISCA, said that two Rwandan peacekeepers were wounded by the anti-balaka after fighting on 23 March in Bangui. The next day, angry youths had set up barricades to block the MISCA troops from entering an unnamed neighborhood.[165] On 30 March, a group of Christian mourners was attacked by a Muslim who threw a grenade and resulted in 11 deaths, according to the national Red Cross.[166] On 29 March, Chadian peacekeepers that were not a part of MISCA entered Bangui's PK12 district market in a convoy of pick-up trucks at about 15:00 and allegedly indiscriminately opened fire resulting in 30 deaths and over 300 injuries, according to the UN. Some sources indicated they were in Bangui to evacuate Chadians and other Muslims from the anti-balaka. On 3 April, Chad announced the withdrawal of its forces from MISCA, which the UN hoped would prevent further incursions by troops travelling directly from Chad.[167] The first batch of 55 EUFOR troops arrived in Bangui, according to the French army, and carried out its first patrol on 9 April with the intention of "maintaining security and training local officers." France called for a vote at the UNSC the next day and expected a unanimous resolution authorising 10,000 troops and 1,800 police to replace the over 5,000 African Union soldiers on 15 September;[168] the motion was then approved.[169] On 10 April, MISCA troops escorted over 1,000 Muslims fleeing to Chad with a police source saying "not a single Muslim remains in Bossangoa."[170] In the week of 14 May, former Séléka rebels shot and killed a Christian priest in Paoua. The next week, Dimanche Ngodi, an official in Grimari, said that during a clash between the anti-balaka and the former Séléka rebels French MISCA troops intervened resulting in several deaths. Captain Sebastien Isern, spokesman for the French troops, said the anti-balaka group had been "neutralised."[171]

On 28 May, Séléka rebels stormed a Catholic church compound, killing at least 30.[172] On 2 June, the government banned text messaging, deeming it a security threat, after calls for a general strike were made via SMS.[173] On 23 June, anti-balaka forces killed 18 members of the mostly Muslim village of Bambari. Several young Séléka took revenge against this attack the same day by killing 10 anti-balaka.[174] On 8 July, 17 people were killed when Séléka forces attacked a Catholic church in Bambari, believing that the church was supposedly sheltering anti-balaka troops.

After three days of talks, a ceasefire was signed on 24 July 2014 in Brazzaville, Republic of Congo.[175] The Séléka representative was General Mohamed Moussa Dhaffane,[175] and the anti-balaka representative was Patrick Edouard Ngaissona.[176] The talks were mediated by Congolese president Denis Sassou Nguesso.[176] The Séléka delegation had pushed for a formalization of the partition of the Central African Republic with Muslims in the north and Christians in the south but dropped that demand in talks.[177] Many factions on the ground claimed the talks were not representative and fighting continued[177] with Séléka's military leader Joseph Zindeko rejected the ceasefire agreement the next day saying it lacked input from his military wing and brought back the demand for partition.[178] Ngaissona told a general assembly of Antibalaka fighters and supporters to lay down their arms and that Antibalaka would be turned into a political party called Central African Party for Unity and Development (PCUD) but he had little control over the loose network of fighters.[179] Further talks were held with Joachim Kokate representing the Antibalaka and Djotodia representing the Exseleka and another ceasefire agreement was reached in Nairobi, Kenya in April 2015. However the talks were not recognized by the French, the UN or the transitional government, who termed the parties "Nairobists".[128] Similar to the previous ceasefire, it had little effect in stopping the fighting.[180] In May 2015, a national reconciliation conference organized by the transition government of the Central Africa Republic took place. This was called the Bangui National Forum. The forum resulted in the adoption of a Republican Pact for Peace, National Reconciliation and Reconstruction and the signature of a Disarmament, Demobilisation, Rehabilitation and Repatriation (DDRR) agreement among 9 of 10 armed groups.[181]

Months after the official dissolution of Seleka it was not known who was in charge of Ex-Seleka factions during talks with Antibalaka until on 12 July 2014, Michel Djotodia[183] was reinstated as the head of an ad hoc coalition of Exseleka[184] which renamed itself "The Popular Front for the Rebirth (or Renaissance) of Central African Republic" (FPRC).[185] Later in 2014, Noureddine Adam led the FPRC and began demanding independence for the predominantly Muslim north, a move rejected by another general, Ali Darassa[7] who formed another Ex-Seleka faction called the "Union for Peace in the Central African Republic" (UPC) which was dominant in and around Bambari[30] while the FPRC's capital is in Bria.[186] Darassa rebuffed multiple attempts to reunify Seleka and threatened FPRC's hegemony.[184] Noureddine Adam declared the autonomous Republic of Logone or Dar El Kuti[187] on 14 December 2015 and intended Bambari as the capital,[187] with the transitional government denouncing the declaration and MINUSCA stating it will use force against any separatist attempt.[182] Another group is the "Central African Patriotic Movement" (MPC) founded by Mahamat Al Khatim.[186]

Since 2014, there has been little government control outside of the capital, Bangui.[30] Armed entrepreneurs have carved out personal fiefdoms in which they set up checkpoints, collect illegal taxes, and take in millions of dollars from the illicit coffee, mineral, and timber trades.[30] By 2017, more than 14 armed groups vied for territory, notably four factions formed by ex-Séléka leaders who control about 60% of the country's territory.[187] With the de facto partition of the country between ex-Séléka militias in the north and east and Antibalaka militias in the south and west, hostilities between both sides decreased[7] but sporadic fighting continued.[188][189] In February 2016, after a peaceful election, the former Prime Minister Faustin-Archange Touadéra was elected president. In October 2016, France announced that it was ending its peacekeeping mission in the country, Operation Sangaris and largely withdrew its troops, saying that the operation was a success.[190]

Tensions erupted in competition between Ex-Seleka militias arising over control of a goldmine in November 2016, where MPC[186] and the FPRC coalition which incorporated elements of their former enemy, the Anti-balaka,[184] attacked UPC.[191][192] The violence is often ethnic in nature with the FPRC associated with the Gula and Runga people and the UPC associated with the Fulani.[7] Most of the fighting was in the centrally located Ouaka prefecture, which has the country's second largest city Bambari, because of its strategic location between the Muslim and Christian regions of the country and its wealth.[186] The fight for Bambari in early 2017 displaced 20,000.[193][192] MINUSCA made a robust deployment to prevent FPRC taking the city and in February 2017, Joseph Zoundeiko, the chief of staff[4] of FPRC who previously led the military wing of Seleka, was killed by MINUSCA after crossing one of the red lines.[192] At the same time, MINUSCA negotiated the removal of Darassa from the city. This led to UPC to find new territory, spreading the fighting from urban to rural areas previously spared. Additionally, the thinly spread MINUSCA relied on Ugandan as well as American special forces to keep the peace in the southeast as they were part of a campaign to eliminate the Lord's Resistance Army but the mission ended in April 2017.[184] By the latter half of 2017, the fighting largely shifted to the Southeast where the UPC reorganized and were pursued by the FPRC and antibalaka with the level of violence only matched by the early stage of the war.[194][195] About 15,000 people fled from their homes in an attack in May and six U.N. peacekeepers were killed - the deadliest month for the mission yet.[196] In June 2017, another ceasefire was signed in Rome by the government and 14 armed groups including FPRC but the next day fighting between an FPRC faction and antibalaka militias killed more than 100 people.[197] In October 2017, another ceasefire was signed between the UPC, the FPRC, and anti-balaka groups and FPRC announced Ali Darassa as coalition vice-president but fighting continued afterward.[194] By July 2018, FPRC, now headed by Abdoulaye Hissène and based in the northeastern town of Ndélé, had troops threatening to move onto Bangui.[198]

In Western CAR, another rebel group, with no known links to Seleka or Antibalaka, called "Return, Reclamation, Rehabilitation" (3R) formed in 2015 reportedly by self-proclaimed[199] general Sidiki Abass, claiming to be protecting Muslim Fulani people from an Antibalaka militia led by Abbas Rafal.[199][200] They are accused of displacing 17,000 people in November 2016 and at least 30,000 people in the Ouham-Pendé prefecture in December 2016.[200] In Northwestern CAR around Paoua, fighting since December 2017 between Revolution and Justice (RJ) and Movement for the Liberation of the Central African Republic People (MNLC) displaced around 60,000 people. MNLC, founded in October 2017,[201] was led by Ahamat Bahar, a former member and co-founder of FPRC and MRC, and is allegedly backed by Fulani fighters from Chad. The Christian[202] militant group RJ was formed in 2013, mostly by members of the presidential guard of former President Ange Felix Patassé, and were composed mainly of ethnic Sara-Kaba.[203] While both groups had previously divided the territory in the Northwest, tensions erupted after the killing of RJ leader, Clément Bélanga,[204] in November 2017.[205]

Atrocities

Human rights abuses include the use of child soldiers, rape, torture, extrajudicial killings and forced disappearances.[206]

Religious cleansing

It is argued that the focus of the initial disarmament efforts exclusively on the Seleka inadvertently handed the anti-Balaka the upper hand, leading to the forced displacement of Muslim civilians by anti-Balaka in Bangui and western CAR.[30] While comparisons were often posed as the "next Rwanda", others[207] suggested that the Bosnian Genocide's may be more apt as people were moving into religiously cleansed neighbourhoods. In 2014, Amnesty International reported several massacres committed by the anti-balakas against Muslim civilians, forcing thousands of Muslims to flee the country.[208] Other sources report incidents of Muslims being cannibalized.[209][210] Much of the tension is also over historical antagonism between agriculturalists, who largely comprise Anti-balaka and nomadic groups, who largely comprise Seleka fighters.[31]

Ethnic violence

There was ethnic violence during fighting between the Ex-Seleka militias FPRC and UPC, with the FPRC targeting Fulani people who largely make up the UPC and the UPC targeting the Gula and Runga people, who largely make up FPRC, as being sympathetic to FPRC.[7] In November 2016 fighting in Bria that killed 85 civilians, FPRC was reported targeting Fulani people in house-to-house searches, lootings, abductions and killings.[211]

Violence against aid workers and crime

In 2015, humanitarian aid workers in the CAR were involved in more than 365 security incidents, more than Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and Somalia. By 2017, more than two thirds of all health facilities have been damaged or destroyed.[212] The crimes are often committed by individuals not associated with any armed rebel groups.[213] There have been jail breaks with more than 500 inmates escaping from Nagaragba Central Prison, including fighters of both Christian and Muslim militias.[214] By 2017, only eight of 35 prisons function and few courts operate outside the capital.[215]

Casualties

Mortality

2013 fatalities were 2,286–2,396+:

- March 2013– Seleka (Coalition of 5 Muslim rebel groups) has overthrown government and seized power.

- March 24 – April 30 – around 130 people killed in Bangui.[216]

- June – 12 villagers killed.[216]

- August – 21 killed during the month.[216]

- 09 September Bouca violence – 73[217]-153[218] killed.

- 06 October – 14 killed.[219]

- 09 October – 30[220]-60[221] killed in clashes.

- 12 October – 6 killed.[222]

- A total of 1000 people were killed in December.[223] 4–10 December – 600[224]-610[225] killed in Bangui and other locations. Two children were beheaded with a total of 16 children killed in Bangui in late December.[226]

- 2,000+ killed in December and January.[227]

2014 ;

Displaced people

In May 2014, it was reported that around 600,000 people in CAR were internally displaced with 160,000 of these in the capital Bangui. The Muslim population of Bangui dropped 99% from 138,000 to 900.[30] By May 2014, 100,000 people had fled to neighbouring Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of Congo[231] and Chad. As of 2017, there are more than 1.1 million displaced people in a country of about 5 million people, the highest ever recorded in the country,[32] with about half a million refugees outside CAR and about 600,000 internally displaced.[232] Cameroon hosted the most refugees, more than 135,000, about 90% of whom are Fulani, even though they constituted 6% of CAR's population.[233]

International response

Organizations

- African Union – Yayi Boni, then-chairman of the African Union, held a press conference in Bangui, stating, "I beg my rebellious brothers, I ask them to cease hostilities, to make peace with President Bozizé and the Central African people ... If you stop fighting, you are helping to consolidate peace in Africa. African people do not deserve all this suffering. The African continent needs peace and not war."[234] Boni went on to call for dialogue between the current government and the rebels.[234] The African Union suspended the Central African Republic from its membership on 25 March 2013.[235]

On 10 February 2014, the European Union established a military operation entitled EUFOR RCA, with the aim "to provide temporary support in achieving a safe and secure environment in the Bangui area, with a view to handing over to African partners." The French Major General Philippe Pontiès was appointed as a commander of this force.[238]

Countries

- Regional

- Others

See also

- List of conflicts in Africa

- Cahier Africain, a documentary which provides one viewpoint on the conflict

References

- ↑ Looting and gunfire in captured CAR capital. Al Jazeera.com (25 March 2013). Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ 26 villagers killed by militants in Central African Republic. NewsGhana.com.gh (22 November 2015). Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ↑ Central African rebel leader declares autonomous republic. Reuters (15 December 2015). Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- 1 2 "CAR crisis: Meeting the rebel army chief". BBC News. 29 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 Central African Republic president says ready to share power with rebels. Reuters (30 December 2012).

- 1 2 "Seleka, Central Africa's motley rebel coalition", Radio Netherlands Worldwide

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Central African Republic: What's gone wrong?". IRIN. 24 February 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 "More military help sought by UN to protect CAR civilians". The Africa News.Net. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ↑ "Zille warns of 'CAR scandal'".

- 1 2 "Civil.Ge – Georgian Troops Heading to EU Mission in Central African Republic".

- ↑ http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/20141124_CAR.pdf

- ↑ "Conflict Observer Project | Central African Republic: Roots of the Conflict and Actors". Cscubb.ro. 2014-10-29. Retrieved 2018-03-18.

- ↑ "CAR battle claims another SANDF soldier". Enca. South Africa.

- ↑ Radio France Internationale, Hollande discusses DRC presence in CAR with Kabila, 21 May 2014

- ↑ "CrisisWatch Database".

- ↑ Casey-Maslen, Stuart (2014). The War Report: Armed Conflict in 2013. Oxford University Press. p. 411. ISBN 978-0-19-103764-1.

- ↑ Massacre evidence found in CAR Al Jazeera. 8 November 2013.

- ↑ Larson, Krista. "AP: More than 5,000 dead in C. African Republic". AP Bigstory. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- 1 2 Uppsala Conflict Data Program Conflict Encyclopedia, Central African Republic, In depth: The Seleka Rebellion, viewed 16 May 2013, http://www.ucdp.uu.se/gpdatabase/gpcountry.php?id=31®ionSelect=2-Southern_Africa#

- ↑ "Séléka rebels agree on unconditional talks". CAR govt. 29 December 2012.

- ↑ Zuma joins regional leaders over crisis in Central African Republic, BDay Live, by Nicholas Kotch, 19 April 2013, 07:50, http://www.bdlive.co.za/africa/africannews/2013/04/19/zuma-joins-regional-leaders-over-crisis-in-central-african-republic

- 1 2 "CAR rebels 'seize' presidential palace". Al Jazeera. 24 March 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "Centrafrique: Michel Djotodia déclare être le nouveau président de la république centrafricaine" (in French). Radio France International. 24 March 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/publication-type/crisiswatch/2013/crisiswatch-119.aspx

- ↑ "Central African Republic president, PM resign at summit: statement". Reuters. 10 January 2014. Retrieved 2014-01-10.

- ↑ "CAR president Djotodia and PM Tiangaye resign". RFI.

- 1 2 RFI (20 January 2014). "Centrafrique: Catherine Samba-Panza élue présidente de la transition". RFI.

- ↑ "New CAR PM says ending atrocities is priority". Al Jazeera.

- ↑ "RCA: signature d’un accord de cessez-le-feu à Brazzaville". VOA. 24 July 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "One day we will start a big war". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- 1 2 "Displaced and forgotten in Central African Republic". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- 1 2 "Concert Blast Shows Central African Republic Religious Rift". Bloomberg. 21 November 2017. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- 1 2 "HISTORIQUE DE L'OPÉRATION MICOPAX". RÉSEAU DE RECHERCHE SUR LES OPÉRATIONS DE PAIX. 1 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- 1 2 "Central African Republic". European Commission. 10 February 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ↑ Hancock, Stephanie (30 August 2007). "Bush war leaves Central African villages deserted". ReliefWeb. Reuters. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ "Raid on CAR town 'leaves 20 dead'". BBC News. 23 December 2004. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ "Central African Republic: Rebels Call for Dialogue After Capturing Key Town". AllAfrica.com. IRIN. 2 November 2006. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ "Central African Republic: Concern As Civilians Flee, Government Denies Rebel Capture of Third Town". AllAfrica.com. IRIN. 13 November 2006. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ "Central African Republic, rebels sign peace deal". USA Today. Associated Press. 13 April 2007. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ "CAR president dissolves government, vows unity". Taipei Times. Agence France-Presse. 20 January 2009. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ "Touadera names rebels in new Central African Republic govt". Google News. Agence France-Presse. 19 January 2009. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Sayare, Scott (11 January 2013). "Rebel Coalition in the Central African Republic Agrees to a Short Cease-Fire". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ↑ "Le CPJP, dernier groupe rebelle actif en Centrafrique, devient un parti politique". Radio France Internationale. 26 August 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ↑ Ibrahim, Alkhali; Abdraman, Hassan (2012-08-20). "RCA: Protocole d'accord militaro-politique contre le régime de Bozizié". CPJP-Centrafrique (Press release). Retrieved 2013-03-31.

- ↑ "Central African Republic: Rebels attack 3 towns". The Big Story. Bangui, CAR. 17 September 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ↑ "Centrafrique : un civil tué par des hommes armés dans l'est (militaires)". Bangui, CAR: ReliefWeb. Agence France-Presse. 13 November 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ↑ "Centrafrique/rébellion: un gendarme et deux civils tués dans une attaque proche de Bangui (gendarmerie)". ReliefWeb. Bangui, CAR. Agence France-Presse. 14 November 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ↑ Agence France-Presse (21 September 2012). "C.African army kills rebel group official". Bangui, CAR: Google News. Archived from the original on 20 February 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ↑ Col. Alkassim (15 September 2012). "communiqué de presse de l'alliance CPSK-CPJP". OverBlog. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ Radio Ndeke Luka (21 September 2012). "Hassan Al Habib " HA " de la CPJP Fondamentale abattu par les FACA à Dékoa". Radio Ndeke Luka. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ↑ Agence France-Presse (13 November 2012). "Centrafrique : un civil tué par des hommes armés dans l'est (militaires)". ReliefWeb. Bangui, CAR. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ↑ "Heavy fighting in northern CAR, many flee: military". Bangui, CAR: Google News. Agence France-Presse. 10 December 2012. Archived from the original on 20 February 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ↑ "A rebel attack on a Central African Republic town left at least four dead and 22 government troops captured by the rebels, sources said Saturday.", Radio Netherlands Worldwide

- ↑ "Central Africa says repelled rebel attack". ReliefWeb. Bangui, CAR. Agence France-Presse. 11 December 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ↑ "Three rebel groups threaten to topple C.African regime". ReliefWeb (AFP). 18 December 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ↑ Ngoupana, Paul-Marin (18 December 2012). "CAR rebels take diamond mining town, kill 15 soldiers". AlertNet. Reuters. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ Marboua, Hippolyte (18 December 2012). "2,000 Troops From Chad to Fight CAR Rebels". ABC News. Associated Press. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ Panika, Christian (18 December 2012). "Chad troops enter Central Africa to help fight rebels: military". Google News. Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ "CentrAfrica rebels refuse pull-back, Chad offers talks". Google News. Agence France-Presse. 20 December 2012. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ↑ "Le FPR soutient l'UFDR dans son combat contre le Dictateur Bozizé" (Press release). FPR. 18 December 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ↑ "Centrafrique : Le FDPC d'Abdoulaye Miskine a rejoint la coalition Séléka". Journal de Bangui. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ↑ "CAR rebels seize biggest, most southern town yet". Reuters. 23 December 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ "Central African rebels seize another town: military". France 24. Agence France-Presse. 25 December 2012. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ "Violent protests erupt at the French embassy in Bangui". France 24. 26 December 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- 1 2 Ngoupana, Paul-Marin (26 December 2012). "Central African Republic wants French help as rebels close in on capital". Reuters. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ "Central African rebels advance on capital". Al Jazeera. 28 December 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ↑ "US evacuates Americans from Central African Republic capital as rebels close in". NBC News. 27 December 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ↑ Panika, Christian (28 December 2012). "CAR leader appeals for help to halt rebel advance". The Daily Star. Beirut. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ↑ C. Africa army repelled trying to retake rebel-held city. France 24 (29 December 2012). Archived 11 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Fresh fighting in the C. African Republic as crisis grows". The Star (Malaysia), 29 December 2012.

- ↑ "C. Africa Army Retreat Puts Rebels One Step From Capital". Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 2013-01-28. . AFP (31 December 2012).

- ↑ Residents flee Bangui as rebels halt for talks Archived 30 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine.. Pakistan Observer (30 December 2012).

- 1 2 Sayare, Scott (2 January 2013). "Central Africa on the Brink, Rebels Halt Their Advance". The New York Times.

- ↑ Look, Anne (3 January 2013) CAR President Sacks Defense Minister. Voice of America. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ "South Africa to send 400 soldiers to CAR". Al Jazeera. 6 January 2013.

- ↑ "Central African Republic: Central African Journalist Killed Amidst Revolt". allAfrica. 10 January 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ "Bambari: Une Journaliste Tuée par les Rebelles du Séléka" (blog). Le Réseau des journalistes pour les Droits de l'homme en République Centrafricaine (RJDH-RCA). 7 January 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ Unesco Press (15 January 2013). "Director-General denounces killing of community radio journalist Elisabeth Blanche Olofio in the Central African Republic". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ "Elisabeth Blanche Olofio de la radio communautaire Be Oko de Bambari: assassinée par des éléments de la coalition Séléka". ARC Centrafrique. 7 January 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ "AFRICA/CENTRAL AFRICA – A journalist of a community radio station in Bambari has been killed". The Vatican Today. 8 January 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ Fanga, Khephren (13 January 2013). "Violence against journalists in Central African Republic". Gabo News. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ "Central African Republic, Seleka rebels sign ceasefire agreement". Press TV. 12 January 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ "Prime minister booted from job in Central African Republic, part of peace deal with rebels". The Washington Post. 13 January 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ↑ Patrick Fort, "Tiangaye named Central African PM, says 'hard work' begins", Agence France-Presse, 17 January 2013. Archived 27 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 "Central African Republic ceasefire signed". BBC. 11 January 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ↑ "C. African Republic rebels to form unity government with president, opposition after talks". The Washington Post. 11 January 2013. Archived from the original on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ↑ "CAR Rebels Break Terms of Cease-Fire". VOA. 23 January 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- 1 2 "Central African Republic Seleka rebels 'seize' towns". BBC. 21 March 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ Ngoupana, Paul Marin (22 March 2013). "Central African Republic rebels reach outskirts of capital". Reuters. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ "RCA: revivez la journée du vendredi 22 mars" (in French). Radio France International. 22 March 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- 1 2 "CAR forces 'halt rebel advance'". BBC. 22 March 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ↑ Hippolyte Marboua and Krista Larson, "Central African Republic rebels threaten new fight", Associated Press, 18 March 2013.

- ↑ "Central African Republic rebels reach outskirts of capital". Reuters. 22 March 2013.

- ↑ "Central African Republic rebels enter north of capital Bangui: witness". Reuters.

- ↑ Nossiter, Adam (23 March 2013). "Rebels Push into Capital in Central African Republic". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Central African Republic rebels in capital, France sends troops". Reuters. 23 March 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ Central African Republic rebels in capital, France sends troops. Reuters (23 March 2013). Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ Standard Digital News – Kenya : World : C. African Republic capital falls to rebels, President flees. Standardmedia.co.ke (24 March 2013). Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Central African Republic: Rebels 'take palace as Bozize flees'". BBC News. 24 March 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "Central African Republic rebels seize capital and force president to flee". The Guardian. London. 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "Central African Republic president flees to Cameroon". CTV News. 25 March 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Central African Republic capital falls to rebels, Bozizé flees". Reuters. 24 March 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "200 SA soldiers took on 3 000 rebels – SANDF". 25 March 2013.

- ↑ "SA soldiers took on overwhelming numbers in CAR fire fight – SANDF Chief". DefenceWeb. 24 March 2013. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "South African Troops Are Being Withdrawn From The Central African Republic", April 4, 2013. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- ↑ "IOL Mobile :: Home :: How deadly CAR battle unfolded". Independent Online. South Africa. 17 April 2013.

- ↑ "How deadly CAR battle unfolded". Independent Online. South Africa. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ DispatchLive, "Rebels Claim More SA Soldiers Died in CAR.", April 6, 2013. Accessed January 27, 2016.

- ↑ French troops secure CAR capital airport. Al Jazeera (23 March 2013). Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ "France says no plans to send more troops to C. African Republic". Reuters Alert Net. 24 March 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "French soldiers kill two Indian nationals in CAR". BBC. 26 March 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ↑ https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/220305.pdf

- ↑ "C.African Republic rebel chief to name power-sharing government" Archived 16 April 2013 at Archive.is, Reuters, 25 March 2013.

- ↑ "CAR rebel head Michel Djotodia 'suspends constitution'". BBC News. 25 March 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "Nicolas Tiangaye: C.Africa PM and 'man of integrity'" Archived 14 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine., Agence France-Presse, 27 March 2013.

- ↑ "Centrafrique: Nicolas Tiangaye reconduit Premier ministre", AFP, 27 March 2013 (in French).

- ↑ Pockets of resistance still in Central African Republic. Reuters (27 March 2013). Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ Ange Aboa, "C.African Republic army chiefs pledge allegiance to coup leader" Archived 1 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine., Reuters, 28 March 2013.

- ↑ 78 bodies found in Central African capital (The News Pakistan). Thenews.com.pk (29 March 2013). Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ "Rebels, opposition form government in CentrAfrica: decree", Agence France-Presse, 31 March 2013. Archived 18 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Centrafrique : Nicolas Tiangaye présente son gouvernement d'union nationale", Jeune Afrique, 1 April 2013 (in French).

- ↑ Ange Aboa, "Central African Republic opposition says to boycott new government", Reuters, 1 April 2013.

- ↑ Ange Aboa, "C.African Republic leader accepts regional transition road map", Reuters, 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "C. Africa strongman forms transition council", AFP, 6 April 2013. Archived 18 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Rebel boss Djotodia elected interim C.Africa leader", AFP, 13 April 2013. Archived 18 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Regional leaders recognise C.African Republic rebel chief", Reuters, 18 April 2013.

- ↑ ndjamenapost, 18 April 2013, http://www.ndjamenapost.com/world/item/718-central-african-republic-swears-in-president-michel-djotodia

- 1 2 3 Dukhan, N. (2016). The Central African Republic crisis. Birmingham, UK: GSDRC, University of Birmingham.

- ↑ "Bloodshed in Bangui: A Day That Will Define Central African Republic". Time. 6 December 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ↑ ICG Crisis Watch, http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/publication-type/crisiswatch/2013/crisiswatch-117.aspx

- 1 2 "About". MINUSCA. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ↑ "Central African Republic president, PM resign at summit: statement". Reuters. 10 January 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ↑ New clashes in CAR as presidential vote looms Al Jazeera. 19 Jan 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ↑ "Gunmen attack Muslims fleeing CAR, kill 22, 3 kids". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2014-01-19.

- ↑ "New clashes in CAR as presidential vote looms". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2014-01-30.

- ↑ "Centrafrique : manœuvres politiques à Bangui sur fond de violences". Le Monde.fr.

- ↑ "Centrafrique : Catherine Samba-Panza, maire de Bangui, élue présidente de transition". leparisien.fr.

- ↑ "United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon's Statements".

- ↑ RFI (20 January 2014). "Catherine Samba-Panza, nouvelle présidente de Centrafrique: pourquoi elle". RFI.

- ↑ "Rebel leaders leave Bangui amid CAR violence". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ↑ "United Nations News Centre". UN News Service Section. 10 February 2014.

- ↑ "New CAR PM says ending atrocities is priority". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ↑ "Bodies burnt in CAR lynching". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ↑ Inside Story. "CAR: At a crossroads of conflict". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ↑ "Former C African Republic minister hacked to death". Press TV. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ↑ Braun, Emmanuel (2014-01-24). "Former minister killed as Central African Republic clashes escalate". Reuters. Retrieved 2014-02-06.

- ↑ "CAR to decide on interim leader amid violence". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ↑ "US calls on CAR to end cycle of violence". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2014-02-06.

- ↑ "CAR appoints Bangui mayor as interim leader". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ↑ "UN approves use of force by EU troops in CAR". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ↑ "UN chief warns CAR could break up". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2014-02-21.

- ↑ "United Nations News Centre". UN News Service Section. 14 February 2014.

- ↑ "Ethnic cleansing of CAR's Muslims alleged". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2014-02-21.

- ↑ "Politics blamed for CAR divisions". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2014-02-21.

- ↑ "Muslims in CAR wary of French presence". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2014-02-21.

- ↑ "Central African Republic Conflict: 75 People Killed". International Business Times UK.

- ↑ "France sends new troops as CAR strife deepens". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2014-02-21.

- ↑ "UN chief urges rapid reinforcements for CAR". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2014-02-21.

- ↑ "Muslims hide in CAR church after killings".

- ↑ "Hollande visits French troops in CAR".

- ↑ "UN warns of food crisis in CAR".

- ↑ "Central African Republic situation worrying, but under control: interim president".

- ↑ "UN launches CAR probe to prevent genocide".

- ↑ "BBC News – Letter from Africa: Could the Pope bring peace to CAR?". BBC News.

- ↑ ABC News. "International". ABC News.

- ↑ "CAR mourners killed in grenade attack".

- ↑ "UN: Chad soldiers killed 30 in CAR".

- ↑ "First EU troops arrive in Central Africa".

- ↑ "UN approves peacekeepers for CAR".

- ↑ "African troops help Muslims flee CAR".

- ↑ "CAR violence leaves unarmed people dead".

- ↑ Rebels kill 30 in church raid in Central African Republic Associated Press. 28 May 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2014

- ↑ Central African Republic Bans Text Messages, Says SMS Is A Security Threat International Business Times. 4 June 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014

- ↑ "17 Killed at CAR Church Shielding Thousands of Christians". Christian Post.

- 1 2 "Central African Republic: Factions Approve a Cease-Fire Agreement". The New York Times. Associated Press. 23 July 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- 1 2 Elion, Christian (24 July 2014). "Central African Republic groups sign ceasefire after talks". Reuters. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- 1 2 "Central African Republic factions announce ceasefire". BBC. 24 July 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ↑ "Central African Republic rebel chief rejects ceasefire". BBC News. 25 July 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ↑ "Anti-Balaka group to lay down arms in CAR". Al Jazeera. 30 November 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- ↑ "CAR rebel factions sign ceasefire agreement in Kenya". Al Jazeera. 9 April 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- ↑ Central African Republic militias agree to disarmament deal Reuters. 10 May 2014. Accessed 28 May 2015

- 1 2 "Rebel declares autonomous state in Central African Republic". Reuters. 16 December 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ↑ Crispin Dembassa-Kette, "Central Africa Republic's ousted leader back in charge of Seleka", Reuters, 12 July 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Kleinfeld, Philip (18 May 2017). "Rebel schism drives alarming upsurge of violence in Central African Republic". Irin news. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ↑ Central African Republic: Ex-president re-elected head of rebel movement Associated Press. 13 July 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014

- 1 2 3 4 "The battle of Ouaka in Central African Republic". LaCroix International. 27 February 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Dangerous Divisions: The Central African Republic faces the threat of secession". Enough Project. 15 February 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ↑ "CAR violence rises: 'They shot my children and husband'". Al Jazeera. 12 February 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ "CAR: Four things to know about the conflict in the Central African Republic". MSF. 10 April 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ "French Peacekeepers Pull Out as New Violence Erupts in the Central African Republic". foreign policy magazine. 1 November 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ↑ "Central African Republic: Executions by rebel group". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 "U.N. 'KILLS REBEL COMMANDER' IN CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC AIRSTRIKES". Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ↑ "U.N. air strikes in Central African Republic kill several: militia". Reuters. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- 1 2 "CAR refugees fleeing war suffer in Congo". Irin News. 30 October 2017. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ↑ "Red Cross: 115 bodies found in CAR's Bangassou". Aljazeera. 17 May 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ↑ "Red Cross finds 115 dead in Central African Republic town". ABC. 17 May 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ↑ "Bodies Strewn Across Town After Central African Republic Clashes". Bloomberg. 24 June 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ "Central African Republic: The way of the warlord". France 24. 13 July 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- 1 2 "Central African Republic: Mayhem by New Group". Human Rights Watch. 20 December 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- 1 2 "Newly formed 3R rebel group inflicts horrors in CAR: UN". Al jazeera. 23 December 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ "Honderden mensen op de vlucht voor geweld in Centraal-Afrikaanse Republiek". DeMorgan. 31 December 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ↑ "CAR Gets First Building Block in New National Army". Voice of America. 26 December 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ↑ "Armed groups in CAR". Irinnews. 17 September 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ↑ "Centrafrique : au moins 25 000 nouveaux déplacés dans le nord-ouest". Le Monde. 9 January 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ↑ "In Central African Republic, militia violence leaves villages devastated". AFP. 17 January 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ↑ ICG Crisis Watch, http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/publication-type/crisiswatch/2013/crisiswatch-118.aspx

- ↑ "Deep divisions as CAR violence continues". Al Jazeera. 2014-01-20. Retrieved 2014-02-06.

- ↑ "Christian threats force Muslim convoy to turn back in CAR exodus". the Guardian.

- ↑ "Hatred turns into Cannibalism in CAR". Centre for African news. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ↑ "Insight – Gold, diamonds feed Central African religious violence". Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ↑ "Mass killings as rebels target ethnic Fulanis in Central African Republic". The guardian. 26 November 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ↑ "Central African Republic clashes could trigger humanitarian 'catastrophe' - agencies". Relief Web. 3 March 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ↑ "CAR becomes most dangerous spot for aid workers". VOA. 23 January 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ↑ "Central African Republic: Hundreds Escape Prison Amid Days of Unrest". The New York Times. 28 September 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ↑ "In Central African Republic, "impunity on staggering scale"". VOA. 11 January 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 "CrisisWatch Database". International Crisis Group. Retrieved 2014-01-02.

- ↑ Central African Republic: Death Toll Rises in Battles in Central African Republic.

- ↑ "It is believed to be the single deadliest day of violence confirmed in the northwest since the conflict began, with 115 Christians and 38 Muslims killed in the fighting, Mudge said."

- ↑ Marin, Paul (6 October 2013). "Fourteen killed in clashes in Central African Republic". Reuters. Retrieved 2014-01-02.

- ↑ "30 killed in clashes in Central Africa Republic". Indian Express. 2013-10-08. Retrieved 2014-01-02.

- ↑ Marin, Paul (2013-10-09). "Around 60 dead in clashes in Central African Republic". Reuters. Retrieved 2014-01-02.

- ↑ Location Settings (2013-10-12). "Central Africa violence kills six". News24. Retrieved 2014-01-02.

- ↑ "Four killed in Christian-Muslim clashes in Central African Republic's capital". Reuters. 30 December 2013.

- ↑ Location Settings (2013-12-13). "More than 600 killed in CAR this week". News24. Retrieved 2014-01-02.

- ↑ Cumming-Bruce, Nick (13 December 2013). "Violence in Central African Republic Killed Over 600 in a Week, U.N. Says". The New York Times.

- ↑ "CAR conflict: Unicef says children 'beheaded' in Bangui". BBC. 31 December 2013.

- ↑ "New CAR PM says ending atrocities is priority". Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ↑ Rebel gunmen kill 34 in Central African Republic: officials Reuters. 17 August 2014. Accessed 18 August 2014

- ↑ "Central African Republic: violent sectarian clashes erupt in Bangui". theguardian.com. 26 September 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ↑ "Central African Republic: Clashes leave 25 dead - UN". bbcnews.com. 29 October 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ↑ "The war across the river".

- ↑ "Fresh violence in Central African Republic leads to more displaced". United Nations.

- ↑ "HRW the unravelling - Journey through the Central African Republic crisis". Human Rights Watch.

- 1 2 Marboua, Hippolyte (30 December 2012). "African Union Head Visits Central African Republic". ABC News. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ↑ Dixon, Robyn (25 March 2013). "African Union suspends Central African Republic after coup". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Giannoulis, Karafillis (24 December 2012). "Central Africa: EU worries on the new outbreak". New Europe. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ "EU Urges Talks in Central African Republic". RIA Novosti

- ↑ "EUFOR RCA". European Union External Action. European Union. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ "UN chief slams attacks on towns in Central African Republic". Press TV. 27 December 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ↑ google.com/hostednews Archived 27 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "CAR key players".

- ↑ "Ministério das Relações Exteriores". Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ↑ (9 May 2014) Estonian Troops Leave for Central African Republic news.err.ee (Estonian Public Broadcasting). Retrieved 10 May 2014

- ↑ "CAR leader appeals for help to halt rebel advance". The Daily Star Newspaper – Lebanon.

- ↑ RSA (1 March 2011). "Training and Support provided by the South African Army (SANDF) to the Army of the Central African Republic (CAR)". International Relations and Cooperation. Archived from the original on 28 March 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ Peter Fabricius (4 January 2013). "Shadow over foreign policy planning – IOL News". Independent Online. South Africa. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ IRIN (8 January 2013). "South Africa bolsters its troops in the Central African Republic". Johannesburg. IRIN. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ AFP (22 March 2013). "Afrique du Sud: le président centrafricain Bozizé reçu par Zuma". Pretoria. Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ↑ Underhill, Glynnis; Mmanaledi Mataboge (28 March 2013). "CAR: Timely warnings were ignored". Mail and Guardian. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ↑ Tochia, Christopher (27 March 2013). "Hard questions for South Africa over CAR battle". Associated Press. Johannesburg. Retrieved 28 March 2013.