Kamwina Nsapu rebellion

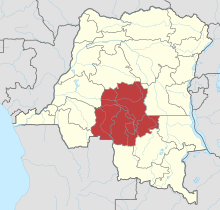

The Kamwina Nsapu rebellion, also spelled Kamuina Nsapu rebellion,[12] is an ongoing rebellion instigated by the Kamwina Nsapu militia against state security forces[13] in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in the provinces of Kasaï-Central, Kasaï, Kasai-Oriental, Lomami and Sankuru.[14][9] The fighting began after the militia, led by Kamwina Nsapu, attacked security forces in August 2016.

There is an ethnic nature to the conflict,[12] with the militia being Luba.[13] It had selectively killed non-Luba.[15]

Background

In 2011, Jean-Pierre Mpandi was designated to succeed his uncle and become the sixth head of Bajila Kasanja clan after returning from South Africa[14] from a conviction in a diamond-trafficking case. His tribal name was Kamwina Nsapu, meaning "black ant". Such chiefs exercise significant control over land and are required to be recognized by the central state even if they are selected according to traditions. That encourages chiefs to support the DRC government to get its endorsement.[14]

His region supported the opposition in the last presidential election, and tensions flared when the government appointed supporters, rather than tribal chiefs, to powerful positions in the local government.[7][16] The central government also refused to recognise Kamwina Nsapu's appointment as chief after he opposed the government's stance. That led him to contest the central government's power, and he began calling for an insurrection in June 2016.[7][17]

Beginning of rebellion

He incited his men with xenophobic language, referring to the regular security forces as foreign mercenaries and an occupation force.[7] He caused a militia, named after him, to launch attacks on the local police.[17] On 12 August 2016, he was killed alongside eight other militiamen and 11 policemen in Tshimbulu.[18] Upon his death, the Congolese Observatory for Human Rights condemned his killing and suggested he should have been arrested instead.[19]

Several of his followers refused to believe that he was dead and escalated the violence by intensifying their attacks on the security forces.[7] As the violence by Kamwina Nsapu's men escalated, the uprising spread, and an increasing number of locals picked up arms against the government. Kamwina Nsapu's death meant that the rebellion effectively fractured into numerous movements, "all fighting for different reasons".[2]

After Kamwina Nsapu's death

In September 2016, Kawina Nsapu's militia captured an area 180 km from Kananga and then captured the Kananga Airport before it was retaken by the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[20] On 26 September 2016, the government announced that in total, 49 people had been killed (27 militiamen, 16 policemen and 6 civilians) and 185 militiamen captured since the fighting began.[21]

In January 2017, four militiamen were killed, and two policemen were wounded.[22] A few days later, the rebels called for the removal of the governor, Alex Kande, and protested the visit of Prime Minister Samy Badibanga.[22] On 31 January 2017, a Roman Catholic priest from St. Alphonsus Parish in Kananga who tried to stop the militia from taking children from schools was kidnapped but was later released.[23]

On 9 February 2017, fighting erupted in Tshimbulu between 300 militiamen and the armed forces in a reprisal attack by the militia. At least six people were killed, including one civilian. By the next day, 60 to 75 were reported killed by the armed forces, while at least two servicemen have been wounded.[24] On 14 February, United Nations human rights spokeswoman Liz Throssell announced that at least 101 people had been killed by government forces between 9 and 13 February, with 39 women confirmed to be among them.[25]

A few days later, a video showing members of the Congolese military killing civilians in the village of Mwanza Lomba was leaked.[26][27] Human Rights Minister Marie-Ange Mushobekwa said that the video had not been authenticated,[28] and Communications Minister Lambert Mende Omalanga said that it had filmed in another country "to destroy the image of the D.R.C."[29]

Two journalists have received death threats for their coverage of the conflict: Sosthène Kambidi of Radio télévision chrétienne in Kananga and Fabrice Mfuamba of Radio Moyo in Tshimbulu.[30]

On 18 February 2017, the Grand Séminaire de Malole (Great Seminary of Malole) in Kananga was ransacked by Kamwina Nsapu militants.[31][32] It was the first time that they attacked a Roman Catholic target.[32] Shortly after the attack, both Félicien Mwanama Galumbulula, the Bishop of Lwiza, and Laurent Monsengwo Pasinya, the Archbishop of Kinshasa, condemned the violence,[33] and Justin Milonga, the vice governor of Kasaï-Central, called for the Kamwina Nsapu fighters to negotiate with the government.[34] MONUSCO troops also toured Nganza and Malole in Kananga to calm the situation.[31]

As a result of the clashes, many parents have stopped sending their children to school.[35] However, on 26 February 2017, Justin Milonga, the vice governor of Kasaï-Central, said that the "insanity" needed to end and that children should resume going to school.[35]

On 15 April 2017, the government returned the body of Kamwina Nsapu to the militia, one of its key demands, as a way of easing tensions and recognised his successor, Jacques Kabeya Ntumba, as a customary chief, as failure to recognize Nsapu had been a trigger for the fighting.[12] As the conflict continued to spread and escalate in violence, the government sent hardened troops from eastern Congo to fight the Kamwina Nsapu militia. The commanders of these reinforcements were "notorious for their brutality" and even included a former warlord who had once been convicted by the government to death for his extreme behavior. Increasing reports surfaced of the military having massacred both captured rebels and Luba civilians who were suspected of supporting the insurgency.[1] MONUSCO estimated that Congolese "state agents" had carried out 1,176 extrajudicial killings against protesters and anti-government activists in 2017, and that most of these killings occurred in areas affected by the Kamwina Nsapu rebellion.[36]

By early 2018, the government had retaken most of the areas in Kasaï and the surrounding regions which had previously been held by insurgents. Nevertheless, fighting continued and a new surge of violence in February 2018 caused about 11,000 people in Kasaï to flee their homes.[11] The United Nations estimated that about 5,000 people had been killed overall during the fighting by August 2018, though the violence did "still fall short of genocide".[6]

Militia

The Kamwina Nsapu rebels are only loosely connected and operate in various autonomous factions.[2] They lack an "identifiable leader" since Kamwina Nsapu's death,[7][12] but individual factions are known to have leaders such as "General" Gaylord Tshimbala[2] and opposition politicians are rumoured to support the uprising.[7][12] The rebels are united in their opposition against the government[2] and have adopted red as unifiying colour of their uprising.[1] Kamwina Nsapu fighters thus usually identify themselves by wearing red headbands or armbands.[7]

Although relatively poorly armed, with most of their weaponry looted or stolen from the Congolese security forces,[7] the rebels are strongly motivated by their belief in various forms of witchcraft:[2] Many Kamwina Nsapu rebels believe in gaining magical protection from harm[1][2] by wearing fetishes,[2] specific leaves,[29][7] and protective amulets.[7] Elements of the Kamwina Nsapu militia have been described as "cultlike" due to their beliefs. For example, recruits are reportedly forced to walk through fire and told that by undergoing the initiation ritual, they will be resurrected if they are killed in battle.[1] Some fighters also believe that wooden weapons can be transformed into functioning guns by magical rituals.[2]

The militia has also been noted for its extensive recruitment of child soldiers. Experts consider it likely that most of the rebels are children.[18][1] Child soldiers are promised jobs and money and are often given drugs and alcohol in order to motivate them to fight.[1][2]

Its splintered nature causes the rebellion to have no clear goals.[2] Common demands by members of the militia are, however, the return of and the proper burial of their slain leader, which the government conceded in March or April 2017,[7][12] reparations for the chief's family, the restoration of damaged hospitals and schools by the central authorities, "social and economic development of the region" and the release of imprisoned rebels as well as civilians. Since February 2017, a purported spokesman of the group has also demanded the implementation of the agreement between Kabila and the opposition after the December 2016 Congolese protests.[7]

Atrocities

Ethnic cleansing

The conflict has evolved from a rebellion against the state to involve ethnic violence.[14] Most of the people in the Kamwina Nsapu militia are from the Luba people[13] and are reportedly targeting the Pende and the Chokwe.[14] On 24 March 2017, militiamen reportedly killed and decapitated at least 40 policemen and spared six, who spoke the local Tshiluba language.[15][37]

The Bana Mura militia, a largely-Chokwe group, committed a string of ethnically-motivated attacks against the Luba and Lulua. It has been linked to the government and victims attest that the army and police accompanied it in attacks.[14] It was reported to have committed atrocities such as cutting off toddlers' limbs, stabbing pregnant women and mutilating fetuses,[38] and it is blamed for the murder of 49 minors in 2017.[4]

Child soldiers

Reportedly, half the Kamwina Nsapu militia is under 14,[18] with some being as young as 5,[7] and Congolese authorities claim that it is under the influence of drugs.[18]

Casualties

In June 2017, more than 3,300 people have been killed in violence since October 2016 and 20 villages have been completely destroyed, half of them by government troops, according to the Catholic Church.[39][4]

International reactions

On 11 February 2017, the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) said in a statement that it was "concerned about the persistent conflict in the Kasais".[40] It condemned the "recruitment and use of child soldiers" and "the disproportionate use of force" by the Congolese forces in retaliation.[40]

In his angelus on 16 February 2017, Pope Francis called for an end to the violence, especially the use of child soldiers.[41][42] He said, "I suffer deeply for the victims, especially for so many children ripped from their families and their schools to be used as soldiers."[43]

On 19 February 2017, Mark C. Toner, the Deputy Spokesperson of the US Department of State called for an investigation into the video of the alleged Mwanza Lomba massacre.[27][44]

On 20 February 2017, the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Development also called for an investigation into the video.[45][46] In an official statement, it said, "France condemns the bloody violence which has rocked the Kasai region for several months. It calls on the Congolese authorities and security forces to shoulder their primary responsibility to protect civilians, fully respecting human rights".[47]

On 13 March 2017, two UN investigators were murdered in Kasai, with both the Congolese government and the Kamunia Nsapu militia naming each other as the culprits. A video published by the Congolese government on April 24 seems to point to the militia.[48]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 de Freytas-Tamura, Kimiko (28 July 2017). "Who's in Congo's Mass Graves? And Why Are Soldiers Guarding Them?". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Byaruhanga, Catherine (24 April 2017). "DR Congo's Kasai conflict: Voodoo rebels take on Kabila". BBC. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ↑ Jean-Jacques Wondo Omanyundu (18 February 2017). Flash DESC : Les images barbares des soldats congolais au Kasaï Central (in French). Kasai Direct. Published 14 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "UN reports 251 killings in DR Congo's Kasai, 62 children among dead". The Independent. 5 August 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ "UN accuses Congo-backed militia of crimes against toddlers, others". The News Nigeria. 20 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 William Eagle (3 August 2018). "UN Investigator: Atrocities in DRC Fall Short of Genocide". Voice of America. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Hoebeke, Hans (21 March 2017). "Kamuina Nsapu Insurgency Adds to Dangers in DR Congo". International Crisis Group. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ Hess, Max (27 July 2017). "Democratic Republic of Congo: Kamwina Nsapu violence foretells deadly conflict". ake. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- 1 2 "Congo-Kinshasa: Kamuina Nsapu Insurgency Adds to Dangers in DR Congo". All Africa. 21 March 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ↑ "One million displaced in DR Congo's Kasai due to violence: UN". Press TV. 21 April 2017.

- 1 2 Lisa Schlein (6 March 2018). "Mounting Inter-Ethnic Tensions in DRC's Kasai Region Threaten New Violence". Voice of America. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Congo government returns tribal leader's body to sooth Kasai tensions". Reuters. 16 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 "DRC's Kasai-Oriental province requires emergency assistance 600,000 says UN". International Business Times. 8 March 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Briefing: The conflict in Kasai, DRC". Irinnews. 31 July 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- 1 2 "Kamwina Nsapu militia kill 40 policemen in DR Congo". Al Jazeera. 26 March 2017.

- ↑ "DR Congo tribal rebellion: What we know". New Vision. 31 March 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- 1 2 "Kasaï-Central: le chef Kamwina Nsapu est mort dans les combats contre les forces de l'ordre". Radio Okapi. 13 August 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "RDC: affrontements meurtriers à Tshimbulu, dans le Kasaï-Central" (in French). Radio France Internationale. 14 August 2016.

- ↑ "Kasaï-Central: l'OCDH condamne la mort du chef milicien Kamwina Nsapu". Radio Okapi. 13 August 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ "Analyse de l'attaque de l'aéroport de Kananga par la milice de Kamwin-Nsapu". Radio Okapi. 26 September 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ "Kananga: 49 morts dans les accrochages entre forces de l'ordre et miliciens" (in French). Radio Okapi. 26 September 2016.

- 1 2 "Au moins quatre morts dans des violences à Kananga, dans le centre de la RDC". Africanews. 28 January 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ↑ "AFRICA/DR CONGO - A priest who opposed the militiamen of Kamuina Nsapu was kidnapped and then released". Vatican.va. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ↑ "En RDC, nouveau décompte macabre en cours dans le Kasaï central" (in French). Radio France Internationale. 10 February 2017.

- ↑ "Congolese soldiers kill at least 101 in militia clashes - U.N." Reuters. 14 February 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ↑ Ross, Aaron (18 February 2017). "Congo probes video showing apparent massacre by soldiers". Reuters. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- 1 2 Tilouine, Joan (20 February 2017). "Massacre filmé au Kasaï, dans le centre de la RDC". Le Monde. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ "Possible massacre de civils par l'armée en RDC". Le Figaro. 18 February 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- 1 2 Gettleman, Jeffrey (17 February 2017). "Look, They Are Dying': Video Appears to Show Massacre by Congolese Soldiers". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ "RDC: une centaine de Kamuina Nsapu tués à Tshimbulu, selon des sources locales". Radio France International. 14 February 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- 1 2 "RDC: les miliciens de Kamwina Nsapu saccagent le grand séminaire Malole". Radio Okapi. 19 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- 1 2 "RDC: le Grand Séminaire de Malole saccagé dans le Kasaï". Vatican Radio. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ "RDC: le cardinal Monsengwo condamne les attaques contre des édifices de l'église catholique". Radio Okapi. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ "Justin Milonga : "Toutes les voies de négociations sont en train d'être ouvertes avec les miliciens de Kamuina Nsapu"". Radio. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- 1 2 "Après la psychose de Kamwina Nsapu, les élèves du Kasaï-Central appelés à reprendre les cours". Radio Okapi. February 26, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ↑ Jason Burke (25 January 2018). "Congo 'state agents' murdered hundreds in 2017, says UN report". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ↑ "DR Congo: 40 police officers decapitated by militia". Newshub. 26 March 2017.

- ↑ "Congo's violence fuels fears of return to 90s bloodbath". The Guardian. 30 June 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ↑ "DR Congo Kasai conflict: 'Thousands dead' in violence". BBC News. 20 June 2017.

- 1 2 "MONUSCO STRONGLY CONDEMNS THE PERSISTENT VIOLENCE IN THE KASAI PROVINCES". MONUSCO. 11 February 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ↑ Boh, Elvis (20 February 2017). "DR Congo: Pope Francis calls for peace". Africanews. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ↑ "Pope laments plight of child soldiers fighting in Congo". Catholic Herald. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ "Pope prays for victims of violence in DR Congo and Pakistan". Vatican Radio. 19 February 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ↑ Schwartz, Ken (20 February 2017). "US Demands Independent Probe of Alleged Civilian Massacre in DRC". Voice of America. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ "Vidéo de massacre: sous pression, la RDC refuse d'enquêter". La Croix. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ "France calls on DRC to shed light on massacre video". Radio France International. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ "Democratic Republic of Congo - Situation in the Kasai region". French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Development. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ Reuters in Kinshasa. "UN 'utterly horrified' by video appearing to show murder of two experts in Congo | World news". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-02-07.