Cape Town water crisis

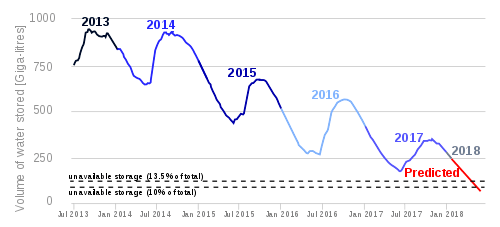

A drought in the Western Cape province of South Africa began in 2015, resulting in a severe water shortage in the region, most notably affecting the City of Cape Town and commercial agriculture. In early 2018, with dam levels predicted to decline to critically low levels by April, the city announced plans for "Day Zero", when if a particular lower limit of water storage was reached, the municipal water supply would largely be shut off, potentially making Cape Town the first major city to run out of water.[1][2][3] Through water saving measures and water supply augmentation, by March 2018 the City had reduced its daily water usage by more than half to around 500 million litres (110,000,000 imp gal; 130,000,000 US gal) per day. Combined with good rains in the winter of 2018, by June 2018 dam levels had increased to 43% of capacity, which enabled the City of Cape Town to announce that "Day Zero" was unlikely for 2019.[4] In September, with dam levels close to 70%, the city began easing water restrictions.[5]

Background

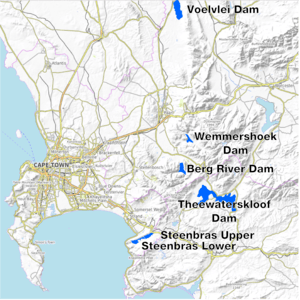

The Cape Town region experiences a Mediterranean climate with warm, dry summers and winter rainfall. Water is supplied largely from the six major dams of the Western Cape Water Supply System which are situated in the nearby mountainous areas.[6] The dams are recharged by rain falling in the catchment areas, largely during the cooler winter months of May to August, and dam levels decline during the dry summer months of November to April during which urban water use increases and irrigation takes place in the agricultural areas.

The City of Cape Town's population has grown from 2.4 million residents in 1995 to an estimated 4.3 million by 2018, representing a 79 percent population increase in 23 years, whereas dam water storage only increased by 15 percent in the same period.[7] In 2016/2017, 64.5% of the City's water supply went to formal residential users, while 3.6 percent went to informal settlements.[8]

From 1950 to 1999, the City's usage of treated water grew at 4% per year in line with the population growth. Peak water usage in 1999 was 335 million cubic metres (335 gigalitres) per year. Planning to accommodate this growth in water demand on the Western Cape Water Supply System commenced as early as 1990.[9] Periods of low winter rainfall in 2000/2001 and 2003/2004 resulted in water restrictions being imposed.[10][11] In about 2003 the City entered into an agreement with the then Department of Water Affairs for the construction of the Berg River Dam and Supplement Scheme and also commenced water demand management. In 2009, the storage capacity of the dams supplying Cape Town was increased by 17 percent from 768 to 898 million cubic metres when the Berg River Dam and Supplement scheme were completed.[12]

In 2007, the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry predicted that the growing demand on the Western Cape Water Supply System would exceed supply if water conservation and demand management measures were not implemented by the City and other municipalities.[13] Although the City's water demand management measures and those of the other urban users were relatively successful in reducing water demand, the severe drought from 2015 to 2017, perhaps with a recurrence interval of about 1 in 300 years, required the City and all users to implement severe restrictions.

Causes

The cause of the water crisis in the Western Cape was the extreme drought that exceeded the planning norms of the Department of Water and Sanitation, which is responsible for the planning of all surface and ground water supplies. It is believed that water scarcity, caused by an extreme drought, was exacerbated by population growth, agricultural usage, invasive plant species, and inadequate response to imposed restrictions. The population of Cape Town has grown by 50 percent in the last decade.[14] In the same period the City's measures to reduce demand (including steeply rising tariffs, pressure management, fixing leaks and publicity) have partially decoupled water use from population growth.[15]

A study conducted by the Climate System Analysis Group at the University of Cape Town undertook statistical analyses and determined that the low rainfall between the years 2015 and 2017 was a very rare and extreme event.[16]

Some scientists believe that the drought may have been exacerbated by climate change with a one degree Celsius increase in temperature over the past century. Models predict that the average temperature in Cape Town will increase by another 0.25 degrees Celsius in the next ten years, which may increase the likelihood and severity of drought. Climate modelling suggests a likely decrease in rainfall, and it has been suggested that the recent drought may be the first evidence supporting this prediction. There is additional concern that several other cities may have similar occurrences of water scarcity.[17]

A concern is that the Western Cape Water Supply System is based on the hydrological records of previous years. Climate change may alter precipitation patterns in the area, leading to less stable sources of water and higher rates of water evaporation. Although agriculture uses about 29% of the water supplied by the Western Cape Water Supply System, it was also severely restricted during the period of drought in line with the assurance of supply.[18]

Timeline

| Water levels as a percentage of total dam capacity by year.[7] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major dams | Capacity (megalitres) | 8 October 2018[19] | 14 May 2018[20] | 15 May 2017 | 15 May 2016 | 15 May 2015 | 15 May 2014 |

| Berg River Dam | 130 010 | 99.4 | 39.2 | 32.4 | 27.2 | 54.0 | 90.5 |

| Steenbras Lower | 33 517 | 91.9 | 35.4 | 26.5 | 37.6 | 47.9 | 39.6 |

| Steenbras Upper | 31 767 | 87.7 | 59.6 | 56.7 | 56.9 | 57.8 | 79.1 |

| Theewaterskloof Dam | 480 188 | 58.8 | 12.0 | 15.0 | 31.3 | 51.3 | 74.5 |

| Voelvlei Dam | 164 095 | 96.2 | 14.5 | 17.2 | 21.3 | 42.5 | 59.5 |

| Wemmershoek Dam | 58 644 | 95.1 | 48.4 | 36.0 | 48.5 | 50.5 | 58.8 |

| Total stored (megalitres) | 898 221 | 684 030 | 191 843 | 190 300 | 279 954 | 450 429 | 646 137 |

| Total % Storage | 76.2 | 21.4 | 21.2 | 31.2 | 50.1 | 71.9 | |

2015-2016

After good rains in 2013 and 2014, the City of Cape Town began experiencing a drought in 2015, the first of three consecutive years of dry winters brought on possibly by the El Niño weather pattern and perhaps by climate change.[21] Water levels in the City's dams declined from 71.9 percent in 2014 to 50.1 percent in 2015.[7] Previous water restrictions had been lifted in 2005, and on 1 January 2016 the City implemented Level 2 restrictions and on 1 November 2016 it elevated these to Level 3, when the Department of Water and Sanitation gazetted water restrictions for urban and agricultural use.

Significant droughts in other parts of South Africa ended in August 2016 when heavy rain and flooding occurred in the interior of the country,[22] but the drought in the Western Cape remained.

2017

The City increased water restrictions to Level 3B on 1 February 2017 and by the end of the dry season in May 2017, the drought was declared the City's worst in a century, with storage in dams being less than 10 percent of their usable capacity.[23] Level 4 water restrictions were imposed on 1 June 2017, limiting the usage of water to 100 litres per person per day.[24] Overall rainfall in 2017 was the lowest since rainfall records commenced in 1933.[25]

With the dry summer season approaching, the City increased its existing water restrictions to Level 4B on 1 July 2017, and to Level 5 on 3 September 2017, banning outdoor and non-essential use of water, encouraging the use of greywater for toilet flushing, and aiming to limit the overall per capita water usage to 87 litres per day, for a total consumption of 500 million litres per day.[18] In order to achieve this target the public were exhorted to limit their personal household usage to 50 litres per capita per day.

By early October 2017, following a low rainfall winter, Cape Town had an estimated five months of storage available before water levels would be depleted.[18] In the same month, the City of Cape Town issued an emergency water plan to be rolled-out in multiple phases depending on the severity of the water shortage. Phase 1 compromising "water rationing through extreme pressure reduction" was implemented immediately. In Phase 2, post "Day Zero", water would have been shut off to most of the system except to places of key water access. Phase 3 would have been the point at which the City would no longer be able to draw water from surface dams in the Western Cape Water Supply System and there would have been a limited period of time before the water supply system fails.[26][27][28]

In mid-October 2017 the City was criticised by some of the water desalination companies for the slow pace of procurement, high level of bureaucracy, lack of urgency, and the inadequate scale of the proposed water supply projects,[29] however on 26 October 2017 it was announced that the Cape Town City Manager would be given special powers to take drought-related actions that would not have to follow the City's normal decision making and approval process. This announcement came after a review of the City's decision making processes that found that "certain aspects of the Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act, the Municipal Finance Management Act and Supply Chain Management Regulations, as well as the Council's own Supply Chain Management Policy, had failed to adequately provide for the City of Cape Town to 'deal effectively and timeously' with the disaster."[30]

In December 2017, the Department of Water and Sanitation advised all users of the increased restrictions of 45% for urban users and 60% for agriculture.

2018

.jpg)

In January 2018, the Department of Water and Sanitation gazetted the restrictions of December 2017 and the City declared Level 6 water restrictions of 87 litres per person per day. In February 2018, the City increased restrictions to Level 6B limiting usage to 50 litres per person per day.[18]

On 24 January 2018, the Premier of the Western Cape Helen Zille, stated that the "provision of bulk water supply is a National Government mandate" as the Department of Water and Sanitation is responsible for funding the expansion of the water supplies from surface and ground water sources. The Provincial Cabinet also announced that it was drawing up plans with the South African Police Service for a strategy to deploy officers at water distribution points across the City after "Day Zero".[31]

In mid-January 2018, Cape Town Mayor Patricia de Lille had announced that the City would be forced to shut off most of the municipal water supply if conditions did not change. Level 7 water restrictions, "Day Zero", would be declared when the water level of the major dams supplying the City reached 13.5%. Municipal water supplies would largely be switched off, and residents would have to rely on 149 water collection points around the City to collect a daily ration of 25 litres of water per person.[32][33] This would further affect Cape Town's economy, because employees would have "to take time off from work to wait in line for water".[34] Water supply would be maintained in the City's CBD, in informal settlements (where water is already collected from central locations) and to essential services such as hospitals. At the time of the announcement, "Day Zero" was projected to take place on 22 April 2018, but soon thereafter this was revised to 12 April.[35][36][37] The "Day Zero" projections were based on the fortnightly changes in dam storage levels, assuming that the rates of decline would continue unchanged, with no further rainfall or change in water demand.[38]

The Think Water website of the City of Cape Town had been launched prior to the drought, and during the drought dam levels on the website were updated weekly as was the progress with the various emergency measures planned by the City. In January 2018 the City launched its Water Map which contained an interactive tool to assist users to monitor and compare their water usage with the City's targeted residential usage.

In February 2018, the Groenland Water User Association (a representative body for farmers in the Elgin Grabouw agricultural area near Cape Town) began releasing an additional 10 billion litres of water from their Eikenhof Dam at no cost. This water was transferred into the Upper Steenbras Dam at no cost.[39]

Residential water usage declined significantly under the Level 6B restrictions to a low on 12 March 2018 of 511 million litres per day, the closest yet to the targeted level of 450 million litres per day. Agricultural use also declined significantly after irrigators had used their restricted allocations. As the reductions in water demand took effect after April,[40][41][42][43][38][3] the city moved "Day Zero" back in stages and on 28 June postponed "Day Zero" indefinitely.[44]

As dam levels rose, the national Department of Water and Sanitation announced that bulk water restrictions would remain in place until levels reached 85%.[45] In September, with dam levels close to 70%, the city reduced consumer water restrictions from level 6B to level 5.[5]

Severity of the drought

Research on long-term weather data done by the University of Cape Town found that the period from 2015-2017 had been the driest 3-year period since 1933, and 2017 was the driest year since 1933, and possibly earlier, since comparable data before 1933 was not available. It also found that a drought of this severity would statistically occur approximately once every 300 years.[25]

Impact

The 60% restriction in 2018 of water usage for irrigation resulted in the loss of 37,000 jobs in the Western Cape Province and an estimated 50,000 people being pushed below the poverty line due to job losses, inflation and increases in the price of food.[46] By February 2018, the agricultural sector had incurred R14 billion (US$1.17 billion) in losses due to the water shortage.[47] Analysts "estimate that the water crisis will cost some 300,000 jobs in agriculture and tens of thousands more in the service, hospitality and food sectors".[34]

Urban residents were requested not to flush the toilet after urinating, to flush using rainwater or greywater after defecating, and to reduce the length and frequency of showers. In order to conserve water hand sanitizer was provided in offices and public buildings for use instead of conventional hand-washing. Some cafes began using plastic and paper cups and plates to reduce dishwashing.

The City recommended that residents keep 10 litres of water as an emergency drinking supply in the event of possible temporary interruptions in supply. This resulted in bottle water being sold out at stores after it was delivered. Residents also queued at natural springs to collect water.[34]

Public health

Public health professionals raised concerns about diseases that could be spread via faecal-oral contamination as a result of less hand-washing.

Inadequate sanitation could have lead to diarrhoeal diseases, which kill 2.2 million people every year worldwide, with most deaths occurring among children younger than 5 years of age. With a population of around 4.3 million and a population density of around 1500 per square kilometre it was suggested that this could have lead to diseases like cholera and other spreading rapidly without proper sanitation, especially in the impoverished neighbourhoods of Cape Town. Without clean water the public health consequences could have been increased by insects attracted and reproduced in dirty waters, which might have caused the further spread of diseases.[48]

Officials warned that water-borne illnesses such as cholera, hepatitis A and typhoid fever would "likely become more prevalent" as residents began storing water in contaminated containers.[49]

Public health companies, research centres and health providers were also worried about the impact that the water crisis could have had on health services. Others were thinking ahead of the impact of employees being unable to come to work because of waiting in lines for water.[50]

Risks of storing water

In response to the crisis, City residents started to store rainwater, for irrigation and flushing of toilets. Improvised storage may not be safe for children, and at least one child drowned in a temporary water storage bin set up to try to save rainwater.[51]

Fire risks

There was concern that fire risk would increase as the environment and infrastructure became increasingly dry. This was especially significant for large industrial sites and warehousing as fire on one site could spread more easily to other buildings in close proximity. Fire suppression system might also have failed due to reduced water pressure in higher lying areas.[49][52]

Occupational health risks

Emergency shower and eyewash stations are an essential part of workplace safety for many laboratories and factories. A steady supply of water is necessary in the event of harmful chemical exposure. Many Occupational Health and Safety requirements suggested that emergency showers should be able to pump 75 litres per minute for a minimum of 15 minutes.[53] If these wash stations had been banned or limited, workers who handle highly corrosive chemicals would have been vulnerable.

Vulnerable population

In homes and orphanages, children were one of the most vulnerable groups that could have suffered from health effects of water scarcity. The feeding, washing, and sterilization of items required to care for children is water intensive.[54] Furthermore, If schools in the Western Cape would have had their taps turned off on "Day Zero", 1.1 million children could have been left stranded without water.[55]

Implications and Response of Business

The drought presented challenges to businesses at different stages and intensities, depending on the nature of the business. Businesses responded depending on a combination of government regulation, managerial judgement and access to capital with which to effect changes. There were three broadly identifiable stages, in each of which the intensity of the business response increased:

- Stage One - 2016 to early 2017. Historically, the price of municipal water supplied to businesses had been too low to stimulate voluntary investment in water efficiency measures or alternative sources of supply, even for the most water-intensive companies.

- Stage Two - May 2017 to January 2018. Commercial water tariffs had been increased by the City for a second time in December 2016, causing a total increase of 35% compared with 2015.[56] The increase was insufficient on its own to stimulate large-scale business investment in efficiencies and alternative sources. After the drought was declared a provincial disaster in May 2017 more businesses became concerned about the continuity of supply in the face of potential rationing, and took action to become more efficient or to secure alternative sources of water (e.g. boreholes, rainwater harvesting, etc.).[57]

- Stage Three - January to May 2018. On 1 February the City's Level 6B tariffs came into force, representing for businesses a 104% increase over the previous consumptive use tariff.[58] Coupled with regular updates from the City about the expected date for "Day Zero", a number of companies took this as a trigger to spend significant capital on improving water efficiency and securing alternative supplies.

Implications for Agriculture

The agriculture industry is one of the largest users of water. The wine industry in the Western Cape is a major tourist draw and together with the export fruit industry employs about 340,000 workers and contributes more than 10% to the Province's economy. The wine industry drew 1.5 million tourists in 2017 and together with the export fruit growing sector normally uses about 30% of the water from the sources that also supply Cape Town.[14] Depending on the region, a vineyard needs between 10 and 24 inches of rain to survive. In 2017 local vineyards received on average half their precipitation which resulted in water stress, causing smaller yields. The returns on investment of the local wine and fruit industries are very low although the wine industry produces some of the most popular wines in the world. It was estimated that in 2018 the yield of vineyards would fall by 20% from the 1.4 million tons produced in 2017, and that this would result in a 9% decrease in the volume of wine.[50]

Hydrological poverty

Hydrological poverty tends to trap people that cannot afford to purchase the food or water necessary for their society to become more affluent. During the drought an analyst estimated that 300,000 jobs would be lost in agriculture and tens of thousands more in the associated services, the hospitality and food sectors.[34] In Cape Town it is illegal to sell water from wells or rivers but people could still profit from the transport and labour associated with the delivery of water from other areas. One resident who had been stockpiling water was charging $350 for a barrel of water. This further alienated the more impoverished neighbourhoods and citizens. Those who were using significantly more than the allocated daily water allowance of 50 litres per capita per day were fined between R 500–3000 (US$41–248).[34] Yet this impact further cemented the poverty gap because the fine was relatively small for the wealthy but crippling for less affluent residents.

Government responsibility

Responsibility for the water supply is shared by local, provincial and national government. In terms of the Water Act of 1998 the national government is the "public trustee" of the nation's water resources to ensure that water is "protected, used, developed, conserved, managed and controlled in a sustainable and equitable manner, for the benefit of all persons". It states that "the National Government, acting through the Minister, has the power to regulate the use, flow and control of all water in the Republic."[15] This resulted in tension between the DA-led local and provincial government on the one hand, and the ANC-led national government on the other, with the parties initially blaming each other for the water crisis.[14]

Tourism

There has been a decrease in the tourism sector with a decrease in arrivals, occupancy and feet through attractions in January 2018 when compared to the same period to last year. The accommodation sector has reported a decline in occupancy of 10%.[59]

Positives

This water crisis has increased research and investment in alternative water systems, which may ultimately help prevent other cities from falling into the same degree of water scarcity. If climate change is a reality and the population of urban areas increases then other cities may have to face severe droughts and may need to consider alternative methods of obtaining water.[60]

The potential for a culture change in water usage is also a positive result of the crisis.

Response to the Water Crisis

Municipal emergency water augmentation

The City of Cape Town commissioned three small temporary (2 year contracts) desalination plants (two of 7 megalitres per day and one of 2 megalitres per day capacities) It also drilled a number of boreholes in the vicinity of the urban areas. This water requires further treatment whereas the quality of the water from boreholes that are being drilled in the mountain areas is excellent. A 10 megalitres per day water reuse project is also to be constructed. The total of the additional supplies provided by these measures is small compared with the more than 50% reduction in water usage that was achieved during the drought.[61]

New water market in Cape Town

The National Water Act of 1998 is mainly based on surface water resources, mainly rivers, and also on groundwater and does not address alternative water solutions. With the increase in water demand and decrease of rainfall, alternative water sources need to be considered. The Cape Town water crisis inspired the private sector to step-in and provide alternative solutions. This led to an increase of the sale of water in single use plastic containers which came at the expense of the environment due to the production of additional plastic waste. There was also a significant increase in the sale of water tanks for storing roof water and in the development of private boreholes as well as in the provision of household water treatment facilities.

Although various alternative water supply solutions have been implemented by the private sector, the water regulations do not easily allow citizen and local businesses to go off the municipality’s water supply system.[62] To enable the private sector to contribute to augmenting water service delivery, further changes in local by-laws may need to be implemented.[63]

Water Demand Management

From about 2010 onwards the City's water demand measures successfully reduced the growth in water demand in spite of the significant increase in the population. These measures together with the steeply rising tariffs that has taken place may in part account for the limited savings achieved after the earlier restrictions.

The City's recently published by-laws are aimed at continuing to promote water conservation and demand management and also to provide for the regulation of alternative supplies. The by-laws also specify that water efficient fittings approved by the South African Bureau of Standards should be provided for all new developments and renovations.

Water Tariffs

During the drought a number of property owners and businesses developed alternative sources of supply, some for strategic reasons such as hospitals and factories which depend on water for their operation. On the other hand, the City relies on the sale of water to provide sufficient revenue to manage and maintain its existing water supply and waste water systems whereas low water users obtain their water at no cost or relatively low cost, in many cases at less than the operating cost. Therefore in areas where property valuations are higher in the City has introduced an additional fixed monthly charge in order to compensate for the loss of revenue from users that have developed alternative sources of supply.

Smart Water Management Devices

Smart Water Management Devices are devices which provide real-time, accurate data on water flow and water consumption levels, and can be programmed to control water use at household- or business-level. This is valuable for a consumers who can ensure that they stay within a certain level of consumption, allowing savings on water costs, and also for water suppliers who wish to reduce the overall consumption of water by consumers on account of the lack of water available for supply during a drought.

During the recent drought the City of Cape Town installed a number of water management devices to restrict excess use. These devices were programmed to shut off automatically if more than 350 litres was consumed by a household during a 24 hour period. It is the City's future intention to provide smart water metering to combine this with data analytics.

References

- ↑ Cassim, Zaheer (19 January 2018). "Cape Town could be the first major city in the world to run out of water". USA Today.

- ↑ Poplak, Richard (15 February 2018). "What's Actually Behind Cape Town's Water Crisis". The Atlantic. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- 1 2 York, Geoffrey (8 March 2018). "Cape Town residents become 'guinea pigs for the world' with water-conservation campaign". The Globe and Mail.

- ↑ Myburgh, Janine (29 June 2018). "Chamber delighted by Day-Zero's death". Cape Messenger.

- 1 2 Pitt, Christina (10 September 2018). "City of Cape Town relaxes water restrictions, tariffs to Level 5". News24.

- ↑ Welz, Adam (1 March 2018). "Awaiting Day Zero: Cape Town Faces an Uncertain Water Future". Yale Environment 360.

- 1 2 3 Bohatch, Trevor (16 May 2017). "What's causing Cape Town's water crisis?". Cape Town: Ground Up. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- ↑ Makou, Gopolang (21 August 2017). "Do Formal Residents Use 65% of Cape Town's Water?". Africa Check.

- ↑ Streek, Barry (26 April 1990). "Cape Town will run out of water in 17 years". Cape Times.

Water supplies for the Cape Town area are expected to dry up in 17 years time, the Water Research Commission (WRC) disclosed yesterday. "It is estimated that known fresh water supplies for the Cape Town metropolitan area will be fully committed by the year 2007," it said in its annual report tabled in Parliament yesterday. "Thereafter the reclamation of purified sewage effluent to augment supplies is a distinct possibility".

- ↑ Basholo, Zolile (4 February 2016). "Overview of Water Demand Management Initiatives: A City of Cape Town Approach" (PDF). City of Cape Town.

- ↑ Steenkamp, Willem (1 January 2005). "'We needed to build more dams a decade ago'".

- ↑ "Cape Town's water supply boosted". City of Cape Town. 17 March 2009. Archived from the original on 27 March 2009.

- ↑ "Western Cape Water Reconciliation Strategy Newsletter 5" (PDF). Department of Water Affairs and Forestry. March 2009.

- 1 2 3 Saunderson-Meyer, William. "Commentary: In drought-hit South Africa, the politics of water". U.S. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- 1 2 "Facts and myths about Cape Town's water crisis". Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- ↑ "Facts are few, opinions plenty… on drought severity again". www.csag.uct.ac.za. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- ↑ Jackson, Randal. "Global Climate Change: Effects". Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- 1 2 3 4 "City of Cape Town Water Outlook 2018 Report" (PDF). City of Cape Town. Retrieved 2018-07-19.

- ↑ "City of Cape Town: Water Dashboard" (PDF). City of Cape Town. 8 October 2018. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ↑ "City of Cape Town: Water Dashboard" (PDF). City of Cape Town. 14 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ↑ "Frequently asked questions about South Africa's drought". Cape Town: Africa Check. 3 February 2016. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- ↑ Masinde, Muthoni (18 August 2016). "Southern Africa faces floods after drought". Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- ↑ Van Dam, Derek (31 May 2017). "Cape Town contends with worst drought in over a century". CNN.com. CNN. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- ↑ Etheridge, Jenna (31 May 2017). "City of Cape Town approves Level 4 water restrictions".

- 1 2 Wolski, Piotr (23 January 2018). "How severe is Cape Town's drought? A detailed look at the data". News24.

- ↑ Bosman, Richard (October 2017). "Critical Water Shortages Disaster Plan Summary" (PDF). City of Cape Town. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ↑ De Lille, Patricia (4 October 2017). "Op-Ed: The City of Cape Town's Critical Water Shortages Disaster Plan | Daily Maverick". www.dailymaverick.co.za. City of Cape Town. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ↑ "Day Zero FAQs" (PDF). City of Cape Town. 5 April 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ↑ Morris, Michael (14 October 2017). "City of Cape Town's water 'bungle' | Weekend Argus". Weekend Argus. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- ↑ News24 (26 October 2017). "Cape Town city manager given special powers to deal with water crisis - NEWS & ANALYSIS". www.politicsweb.co.za. Retrieved 2017-12-01.

- ↑ "Government must refund Cape Town for cost of managing the water crisis". 24 January 2018. Retrieved 2018-01-26.

- ↑ Harrison, Aletta; Janse van Rensburg, Alet (26 January 2018). "JP Smith answers Day Zero questions: 'It's going to be really unpleasant'". News24.

- ↑ "Borehole rules? Can you use sea water to flush? - The City of Cape Town answers your questions". GroundUp. 30 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "'I Knew We Were in Trouble.' What It's Like to Live Through Cape Town's Massive Water Crisis". TIME.com. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- ↑ Baker, Aryn (15 January 2018). "Cape Town Is 90 Days Away From Running Out of Water". Time. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ↑ Thom, Liezl (17 January 2018). "Drought-stricken Cape Town, South Africa, could run out of water by April's 'day zero'". ABC News. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ↑ Brandt, Kevin (23 January 2018). "Day Zero Brought Forward, CT Officials Prepare for Worst".

- 1 2 Neilson, Ian (20 February 2018). "Statement by the City's Executive Mayor, Alderman Ian Neilson: Defeating Day Zero is in sight if we sustain our water-saving efforts". City of Cape Town.

- ↑ "WATCH: Cape Town gets 10bn litres of water". www.enca.com. 6 February 2018. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ↑ Said-Moorhouse, Lauren; Mezzofiore, Gianluca. "Cape Town cuts water use limit by nearly half". CNN. Retrieved 2018-02-03.

- ↑ CNN, Lauren Said-Moorhouse,. "Cape Town 'Day Zero' delayed as agricultural water use drops". CNN. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ↑ "#DayZero pushed back to June, as drought declared a national disaster". News24. 13 February 2018.

- ↑ "South Africa: Day Zero pushed back to June". aljazeera.com. 2018-02-15. Retrieved 2018-02-16.

- ↑ Narrandes, Nidha (14 March 2018). "Cape Town water usage lower than ever". Cape Town etc.

- ↑ "Western Cape edges closer to an end to the drought as dam levels continue to rise". News24. 12 July 2018.

- ↑ DIANA NEILLE, MARELISE VAN DER MERWE & LEILA DOUGAN. "Cape Of Storms To Come". features.dailymaverick.co.za. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- ↑ Phakathi, Bekezela (5 February 2018). "Farmers lose R14bn as Cape drought bites". Business Day. Retrieved 2018-02-07.

- ↑ Head, Tom (2017-10-10). "Cape Town water crisis: With drought, comes the horror of disease". The South African. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- 1 2 "Water related FAQs" (PDF). City of Cape Town. 15 March 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- 1 2 "Cape Town water crisis: South African wine vineyard harvest will be hit by drought — Quartz". qz.com. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- ↑ https://www.iol.co.za/capeargus/news/cape-toddler-drowns-in-bucket-used-for-water-saving-12394271

- ↑ "Western Cape Water Crisis: How resilient is your organization in the face of the current water crisis?" (PDF). PWC. December 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ↑ "Day Zero: The impact of Cape Town's water shortage on public health | Public Health". Public Health. 2018-02-05. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- ↑ "Vulnerable fear Cape Town's water shut-off". News24. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- ↑ "Water crisis: Day Zero could affect a million children". www.enca.com. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- ↑ Siebrits, Raymond (Feb 2017). "GreenCape Water Sector Market Intelligence Report 2017" (PDF). www.greencape.co.za/market-intelligence. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ↑ "49 percent of Cape Town business says drought is becoming a threat to their survival". Cape Business News. 29 October 2017.

- ↑ Reddick, Jane (February 2018). "GreenCape Water Sector Market Intelligence Report 2018" (PDF). GreenCape. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ↑ "CTT Research Report April 2018" (PDF). Cape Town Tourism. 24 July 2018.

- ↑ "Cape Town is almost at the feared 'Day Zero'". The Independent. 2018-03-02. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- ↑ "Why Cape Town Is Running Out of Water, and Who's Next". National Geographic. 2018-03-05. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- ↑ "Businesses in W Cape plan to get off water grid - SABC News - Breaking news, special reports, world, business, sport coverage of all South African current events. Africa's news leader". SABC News - Breaking news, special reports, world, business, sport coverage of all South African current events. Africa's news leader. 2018-07-12. Retrieved 2018-07-19.

- ↑ Green Cape. "Water Installation Guidelines" (PDF).

.svg.png)