Calcium lactate

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

calcium 2-hydroxypropanoate | |

| Other names

calcium lactate 5-hydrate, calcium lactate, 2-hydroxypropanoic acid calcium salt pentahydrate | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.011.278 |

| E number | E327 (antioxidants, ...) |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C6H10CaO6 | |

| Molar mass | 218.22 g/mol |

| Appearance | white or off-white powder, slightly efflorescent |

| Density | 1.494 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 240 °C (464 °F; 513 K) (anhydrous) 120 °C (pentahydrate) |

| L-lactate, anhydrous, g/100 mL: 4.8 (10 °C), 5.8 (20 °C), 6.7 (25 °C), 8.5 (30 °C);[1][2] 7.9 g/100 mL (30 °C) | |

| Solubility | very soluble in methanol, insoluble in ethanol |

| Acidity (pKa) | 6.0-8.5 |

Refractive index (nD) |

1.470 |

| Pharmacology | |

| A12AA05 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Flash point | Not applicable |

| No data | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

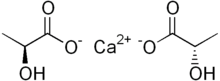

Calcium lactate is a white crystalline salt with formula C

6H

10CaO

6, consisting of two lactate anions H

3C(CHOH)CO−

2 for each calcium cation Ca2+

. It forms several hydrates, the most common being the pentahydrate C

6H

10CaO

6·5H

2O.

Calcium lactate is used in medicine, mainly to treat calcium deficiencies; and as a food additive with E number of E327. Some cheese crystals consist of calcium lactate.[3][4]

Properties

The lactate ion is chiral, with two enantiomers, D (−,R) and L (+,S). The L isomer is the one normally synthesized and metabolized by living organisms, but some bacteria can produce the D form or convert the L to D. Thus calcium lactate also has D and L isomers, where all anions are of the same type.[5]

Some synthesis processes yield a mixture of the two in equal parts, resulting in the DL (racemic) salt. Both the L and the DL forms occur as crystals on the surface of aging Cheddar cheese.[5]

The solubility of calcium L-lactate in water increases significantly in presence of d-gluconate ions, from 6.7 g/dl) at 25 °C to 9.74 g/dl or more.[1][2] Paradoxically, while the solubility of calcium L-lactate increases with temperature from 10 °C (4.8 g/dl) to 30 °C (8.5 g/dl), the concentration of free Ca2+

ions decreases by almost one half. This is explained as the lactate and calcium ions becoming less hydrated and forming a complex C

3H

5O

3Ca+

.[2]

The DL (racemic) form of the salt is much less soluble in water than the pure L or D isomers, so that a solution that contains as little as 25% of the D form will deposit racemic DL-lactate crystals instead of L-lactate.[6]

The pentahydrate loses water in a dry atmosphere between 35 and 135 °C, being reduced to the anhydrous form and losing its crystalline character. The process is reversed at 25 °C and 75% relative humidity.[7]

Preparation

Calcium lactate can be prepared by the reaction of lactic acid with calcium carbonate or calcium hydroxide.

Since the 19th century, the salt has been obtained industrially by fermentation of carbohydrates in the presence of calcium mineral sources such as calcium carbonate or calcium hydroxide.[8]:p200[9][10] Fermentation may produce either D or L lactate, or a racemic mixture of both, depending on the type of organism used.[11]

Uses

Medicine

Calcium lactate has several uses in human and veterinary medicine.

Calcium lactate is used in medicine as an antacid.

Calcium lactate is also used to treat hypocalcaemia (calcium deficiencies). It can be absorbed at various pHs, thus it does not need to be taken with food. However, in this use it has been found to be less convenient than calcium citrate.[12]

In the early 20th century, oral administration of calcium lactate dissolved in water (but not in milk or tablets) was found to be effective in prevention of tetany in humans and dogs with parathyroid insufficiency or who underwent parathyroidectomy.[13][14]

The compound is also found in some over the counter mouth washes.

Calcium lactate (or other calcium salts) is antidote for soluble fluoride ingestion[15]:p165 and hydrofluoric acid.

Food industry

The compound is a food additive classified by the United States FDA as Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS), for uses as firming agent, a flavor enhancer or flavoring agent, a leavening agent, a nutritional supplement, and a stabilizer and thickener.[16]

Calcium lactate is an ingredient in some baking powders containing sodium acid pyrophosphate. It provides calcium in order to delay leavening.[17]:p933

Calcium lactate is added to sugar-free foods to prevent tooth decay. When added to chewing gum containing xylitol, it increases the remineralization of tooth enamel.[18]

The compound is also added to fresh-cut fruits, such as cantaloupes, to keep them firm and extend their shelf life, without the bitter taste caused by calcium chloride, which can also be used for this purpose.[19]

Calcium lactate is used in molecular gastronomy as a flavorless fat-soluble agent for plain and reverse spherification. It reacts with sodium alginate to form a skin around the food item.

Animal feeds

Calcium lactate may be added to animal rations as a source of calcium.[20]

Chemistry

The compound was formerly an intermediate in the preparation of lactic acid for food and medical uses. The impure acid from various sources was converted to calcium lactate, purified by crystallization, and then converted back to acid by treatment with sulfuric acid, which precipitated the calcium as calcium sulfate. This method yielded a purer product than would be obtained by distilaltion of the original acid.[8]:p180 Recently ammonium lactate has been used as an alternative to calcium in this process.[10]

Water treatment

Calcium lactate has been considered as a coagulant for removing suspended solids from water, as a renewable, non-toxic, and biodegradable alternative to aluminum chloride AlCl

3.[21]

Bioconcrete

Addition of calcium lactate substantially increases the compressive strength and reduces water permeability of bioconcrete, by enabling bacteria such as Enterococcus faecalis, Bacillus cohnii, Bacillus pseudofirmus and Sporosarcina pasteurii to produce more calcite.[22][23][24]

See also

References

- 1 2 Martina Vavrusova, Merete Bøgelund Munk, and Leif H. Skibsted (2013): "Aqueous Solubility of Calcium l-Lactate, Calcium d-Gluconate, and Calcium d-Lactobionate: Importance of Complex Formation for Solubility Increase by Hydroxycarboxylate Mixtures". Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry, volume 61 issue 34, pages 8207–8214. doi:10.1021/jf402124n

- 1 2 3 Martina Vavrusova, Ran Liang, and Leif H. Skibsted (2014): "Thermodynamics of Dissolution of Calcium Hydroxycarboxylates in Water". Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry, volume 62, issue 24, pages 5675–5681. doi:10.1021/jf501453c

- ↑ Stephie Clark & Shantanu Agarwal (April 27, 2007). "Chapter 24: Cheddar and Related Hard Cheeses. 24.6: Crystal Formation". In Y. H. Hui. Handbook of Food Products Manufacturing (1st ed.). Wiley-Interscience. p. 589. ISBN 978-0470049648.

- ↑ Phadungath, Chanokphat (2011). The Efficacy of Sodium Gluconate as a Calcium Lactate Crystal Inhibitor in Cheddar Cheese (Thesis). University of Minnesota. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- 1 2 G.F. Tansman, P.S. Kindstedt, J.M. Hughes (2014): "Powder X-ray diffraction can differentiate between enantiomeric variants of calcium lactate pentahydrate crystal in cheese". Journal of Dairy Science, volume 97, issue 12, pages 7354–7362. doi:10.3168/jds.2014-8277

- ↑ Gil Fils Tansman (2014): Exploring the nature of crystals in cheese through X-ray diffraction Masters Dissertation, University of Vermont

- ↑ Yukoh Sakata, Sumihiro Shiraishi, Makoto Otsuka (2005): "Characterization of dehydration and hydration behavior of calcium lactate pentahydrate and its anhydrate". Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, volume 46, issue 3, pages 135–141. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2005.10.004

- 1 2 H. Benninga (1990): "A History of Lactic Acid Making: A Chapter in the History of Biotechnology". Volume 11 of Chemists and Chemistry. Springer, ISBN 9780792306252

- ↑ Kook Hwa Choi, Yong Keun Chang, and Jin-Hyun Kim (2011) "Optimization of Precipitation Process for the Recovery of Lactic Acid". KSBB Journal, volume 26, pages 13-18. (Abstract)

- 1 2 "A gypsum-free, energy-saving route to lactic acid" Chemical Engineering, July 1, 2009.

- ↑ Rojan P. John, K. Madhavan Nampoothiri, Ashok Pandey (2007): "Fermentative production of lactic acid from biomass: an overview on process developments and future perspectives" Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, volume 74, issue 3, pages 524–534 doi:10.1007/s00253-006-0779-6

- ↑ Deborah A. Straub (2007): "Calcium Supplementation in Clinical Practice: A Review of Forms, Doses, and Indications". Nutrition in Clinical Practice, volume 22, issue 3, pages 286–296. doi:10.1177/0115426507022003286

- ↑ Sloan J. Wilson (1938): "Postoperative Parathyroid Insufficiency and Calcium Lactate". Archives of Surgery, volume 37, issue 3, pages 490-497. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1938.01200030139008

- ↑ A.B. Luckhardt and B. Goldberg (1923): "Preservation of the Life of Completely Parathyroidectomized Dogs by Means of the Oral Administration of Calcium Lactate." Journal of the American Medical Association, volume 80, issue 2, pages 79-80. doi:10.1001/jama.1923.02640290009002

- ↑ Carolyn A. Tylenda (2011): "Toxicological Profile for Fluorides, Hydrogen Fluoride, and Fluorine (Update)". DIANE Publishing. ISBN 9781437930771

- ↑ U. S. Food and Drug Administration (2016): Code of Federal Regulations: Title 21 Volume 3, section 21CFR184.1207 "Calcium lactate", revised April 1, 2016

- ↑ E.J. Pyler (1988), Baking Science and Technology, Sosland Publishing

- ↑ Sudaa, R.; T. Suzukia; R. Takiguchib; K. Egawab; T. Sanob; K. Hasegawa (2006). "The Effect of Adding Calcium Lactate to Xylitol Chewing Gum on remineralization of Enamel Lesions". Caries Research. 40 (1): 43–46. doi:10.1159/000088905. PMID 16352880.

- ↑ Luna-Guzman, Irene; Diane M. Barrett (2000). "Comparison of calcium chloride and calcium lactate effectiveness in maintaining shelf stability and quality of fresh-cut cantaloupes". Postharvest Biology and Technology. 19: 16–72. doi:10.1016/S0925-5214(00)00079-X.

- ↑ B.N. Paul, S. Sarkar, S. S. Giri, S. N Mohanty, P. K. Mukhopadhyay (2006): "Dietary calcium and phosphorus requirements of rohu Labeo rohita fry". Animal Nutrition and Feed Technology, volume 6, issue 2, pages 257-263

- ↑ R. Devesa-Rey, G. Bustos, J. M. Cruz, A. B. Moldes (2012): "Evaluation of Non-Conventional Coagulants to Remove Turbidity from Water". Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, volume 223, issue 2, pages 591–598. doi:10.1007/s11270-011-0884-8

- ↑ J.M. Irwan, L.H. Anneza, N. Othman, A. Faisal Alshalif (2016): "Compressive Strength and Water Penetration of Concrete with Enterococcus faecalis and Calcium Lactate". Key Engineering Materials, volume 705, pages 345-349. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.705.345

- ↑ Renee Mors and Henk Jonkers (2017): "Effect on Concrete Surface Water Absorption upon Addition of Lactate Derived Agent". Coatings, volume 7, issue 4, page 51 doi:10.3390/coatings7040051

- ↑ Moneo, Shannon (11 September 2015). "Dutch scientist invents self-healing concrete with bacteria". Journal Of Commerce. Retrieved 21 March 2018.