Baking powder

Baking powder is a dry chemical leavening agent, a mixture of a carbonate or bicarbonate and a weak acid and is used for increasing the volume and lightening the texture of baked goods. Baking powder works by releasing carbon dioxide gas into a batter or dough through an acid-base reaction, causing bubbles in the wet mixture to expand and thus leavening the mixture.

Baking powder was discovered by English food manufacturer Alfred Bird in 1843.[1] It is used instead of yeast for end-products where fermentation flavors would be undesirable[2] or where the batter lacks the elastic structure to hold gas bubbles for more than a few minutes,[3] or to speed the production. Because carbon dioxide is released at a faster rate through the acid-base reaction than through fermentation, breads made by chemical leavening are called quick breads.

Formulation and mechanism

Most commercially available baking powders are made up of sodium bicarbonate (also known as baking soda or bicarbonate of soda) and one or more acid salts. Typical formulations (by weight) call for 30% sodium bicarbonate, 5-12% monocalcium phosphate, and 21-26% sodium aluminium sulfate. The last two ingredients are acidic: they combine with the sodium bicarbonate and water to produce the gaseous carbon dioxide. The use of two acidic components is the basis of the term "double acting." Another typical acid in such formulations is cream of tartar, a derivative of tartaric acid. Baking powders also include components to help with the consistency and stability of the mixture.[4]

Commercial baking powder formulations are different from domestic ones, although the principles remain the same. Instead of sodium aluminum sulfate, commercial baking powders use sodium acid pyrophosphate as one of the two acidic components.

Baking soda (NaHCO3) is the source of the carbon dioxide. [5] In some jurisdictions, it is required that baking soda must produce at least 10 per cent of its weight of carbon dioxide.[6] The acid-base reaction can be generically represented as shown:[7]

- NaHCO3 + H+ → Na+ + CO2 + H2O

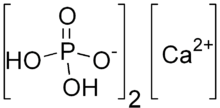

The real reactions are more complicated because the acids are complicated. For example, starting with baking soda and monocalcium phosphate the reaction produces carbon dioxide by the following stoichiometry:[4]

- 14 NaHCO3 + 5 Ca(H2PO4)2 → 14 CO2 + Ca5(PO4)3OH + 7 Na2HPO4 + 13 H2O

Starch component

Baking powders also include components to improve their consistency and stability. The most important additive is cornstarch,[4] although potato starch may also be used. The inert starch serves several functions in baking powder. Primarily it is used to absorb moisture, and thus prolong shelf life by keeping the powder's additional alkaline and acidic components dry so as not to react with each other prematurely. A dry powder also flows and mixes more easily. Finally, the added bulk allows for more accurate measurements.[8]

Single- vs double-acting baking powders

The acid in a baking powder can be either fast-acting or slow-acting.[9] A fast-acting acid reacts in a wet mixture with baking soda at room temperature, and a slow-acting acid does not react until heated. Baking powders that contain both fast- and slow-acting acids are "double-acting"; those that contain only one acid are "single-acting". By providing a second rise in the oven, double-acting baking powders increase the reliability of baked goods by rendering the time elapsed between mixing and baking less critical, and this is the type most widely available to consumers today. Double-acting baking powders work in two phases; once when cold, and once when hot.[10] Common low-temperature acid salts include cream of tartar and monocalcium phosphate (also called calcium acid phosphate). High-temperature acid salts include sodium aluminium sulfate, sodium aluminium phosphate, and sodium acid pyrophosphate.[11] Despite very low acute toxicity, exposure to aluminum salts has raised concerns regarding potential neurotoxicity.

For example, Rumford Baking Powder is a double-acting consumer product that contains only monocalcium phosphate as a leavening acid. With this acid, about two-thirds of the available gas is released within about two minutes of mixing at room temperature. It then becomes dormant because an intermediate form of dicalcium phosphate is generated during the initial mixing. Further release of gas requires the batter to be heated above 140°F (60°C).[12]

History

Early chemical leavening was accomplished by activating baking soda in the presence of liquid(s) and an acid such as sour milk, vinegar, lemon juice, or cream of tartar.[13] These acidulants all react with baking soda quickly, meaning that retention of gas bubbles was dependent on batter viscosity and that it was critical for the batter to be baked before the gas escaped. The development of baking powder created a system where the gas-producing reactions could be delayed until needed.[14]

While various baking powders were sold in the first half of the 19th century, the modern variants in use today were discovered by English chemist and food manufacturer Alfred Bird in 1843.[1] Bird's creation of baking powder enabled the sponge to rise higher in cakes.[15] This new invention, writes cookery author Felicity Cloake, "was celebrated with a patriotic cake", Victoria sponge.[15]

August Oetker, a German pharmacist, made baking powder very popular in Germany when he began selling his mixture to housewives. The recipe he created in 1891 is still sold as Backin in Germany. Oetker started the mass production of baking powder in 1898 and patented his technique in 1903.

In the U.S., Joseph and Cornelius Hoagland developed a baking powder with the help of an employee following the American Civil War. Their formula became known as Royal Baking Powder. The small company eventually moved from Fort Wayne, Indiana, to New York in the 1890s and became the largest manufacturer of baking powder in the U.S..

Eben Norton Horsford, a student of Justus von Liebig, who began his studies on baking powder in 1856, eventually developed a variety he named in honor of Count Rumford. By the mid-1860s "Horsford's Yeast Powder" was on the market as an already-mixed leavening agent, distinct from separate packages of calcium acid phosphate and sodium bicarbonate. His product was packaged in bottles, but Horsford was interested in using metal cans for packing; this meant the mixture had to be more moisture resistant. This was accomplished by the addition of corn starch, and in 1869 Rumford began the manufacture of what can truly be considered baking powder. In 2006 Rumford Baking Powder was designated a National Historic Chemical Landmark in recognition of its significance for making baking easier, quicker, and more reliable.[16]

During World War II, Byron H. Smith, a U.S. inventor in Bangor, Maine, created a substitute product for American housewives, who were unable to obtain cream of tartar or baking powder due to war food shortages. Under the name "Bakewell", Smith marketed a mixture of sodium pyrophosphate mixed with corn starch to replace the acid cream of tartar component of baking powder. When mixed with baking soda, the product behaved like a single-acting baking powder, the only difference being that the acid is sodium acid pyrophosphate. A similar product is marketed today, under the name Bakewell Cream.

How much to use

Generally, one teaspoon (5 g or 1/5 oz) of baking powder is used to raise a mixture of one cup (125 g) of flour, one cup of liquid, and one egg. However, if the mixture is acidic, baking powder's additional acids remain unconsumed in the chemical reaction and often lend an unpleasant taste to food. High acidity can be caused by ingredients such as buttermilk, lemon juice, yogurt, citrus, or honey. When excessive acid is present, some of the baking powder should be replaced with baking soda. For example, one cup of flour, one egg, and one cup of buttermilk requires only ½ teaspoon of baking powder—the remaining leavening is caused by buttermilk acids reacting with ¼ teaspoon of baking soda.

However, with baking powders that contain sodium acid pyrophosphate, excess alkaline substances can sometimes deprotonate the acid in two steps instead of the one that normally occurs, resulting in an offensive bitter taste to baked goods. Calcium compounds and aluminium compounds do not have that problem, though, since calcium compounds that deprotonate twice are insoluble and aluminium compounds do not deprotonate in that fashion.

Moisture and heat can cause baking powder to lose its effectiveness over time, and commercial varieties have a somewhat arbitrary expiration date printed on the container. Regardless of the expiration date, the effectiveness can be tested by placing a teaspoon of the powder into a small container of hot water. If it bubbles vigorously, it is still active and usable.[17]

Different brands of baking powder can perform quite differently in the oven. In one test, six U.S. brands were used to bake white cake, cream biscuits, and chocolate cookies. Depending on the brand, the thickness of the cakes varied by up to 20% (from 0.89 to 1.24 in). It was also found that the lower-rising products made what were judged to be better chocolate cookies.[18]

Substituting in recipes

Substitute acids

As described above, baking powder is mainly just baking soda mixed with an acid. In principle, a number of kitchen acids may be combined with baking soda to simulate commercial baking powders. Vinegar (dilute acetic acid), especially white vinegar, is also a common acidifier in baking; for example, many heirloom chocolate cake recipes call for a tablespoon or two of vinegar.[19] Where a recipe already uses buttermilk or yogurt, baking soda can be used without cream of tartar (or with less). Alternatively, lemon juice can be substituted for some of the liquid in the recipe, to provide the required acidity to activate the baking soda. The main variable with the use of these kitchen acids is the rate of leavening.

Aluminum compounds

Baking powders are available both with and without aluminum compounds.[20] Some people prefer not to use baking powder with aluminum because they believe it gives food a vaguely metallic taste and it is not an essential mineral. Others object because of possible health concerns associated with aluminium intake. In 2015, Cook's Country, an American TV show and magazine,[18] evaluated six baking powders marketed to consumers. They reported that 30% of their testers (n=21) noted a metallic flavor in cream biscuits made with brands containing aluminum.[18]

Use of aluminum based powders was briefly banned in Missouri in 1899 as one producer attempted to discredit others.[21]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Alfred Bird: Egg-free custard inventor and chemist". Birmingham Mail. Retrieved 25 February 2018

- ↑ Matz, Samuel A. (1992). Bakery Technology and Engineering (3 ed.). Springer. p. 54. Retrieved 2009-08-12.

- ↑ McGee, Harold (2004). On Food and Cooking (revised ed.). Scribner-Simon & Schuster. p. 533. Retrieved 2009-08-12.

- 1 2 3 John Brodie, John Godber "Bakery Processes, Chemical Leavening Agents" in Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology 2001, John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/0471238961.0308051303082114.a01.pub2

- ↑ "Chemical Leaveners, Lallemand Baking Update, Vol. 1 No. 12, 1996" (PDF). Lallemand Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2003-03-03. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ↑ Branch, Legislative Services. "Consolidated federal laws of canada, Food and Drug Regulations". laws.justice.gc.ca. Retrieved 2018-07-19.

- ↑ A.J. Bent, ed. (1997). The Technology of Cake Making (6 ed.). Springer. p. 102. Retrieved 2009-08-12.

- ↑ McGee, Harold (2004). On Food and Cooking (revised ed.). Scribner-Simon & Schuster. p. 534. Retrieved 2009-08-12.

- ↑ Lindsay, Robert C. (1996). Owen R. Fennema, ed. Food Chemistry (3 ed.). CRC Press. p. 772. Retrieved 2009-08-12.

- ↑ Corriher, S.O. (2008). BakeWise: The Hows and Whys of Successful Baking with Over 200 Magnificent Recipes. Scribner. ISBN 9781416560838. Retrieved 2014-10-25.

- ↑ Matz, Samuel A. (1992). Bakery Technology and Engineering (3 ed.). Springer. pp. 71–72. Retrieved 2009-08-12.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions". Clabber Girl. Clabber Girl. 2014. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- ↑ Stauffer, Clyde E. (1990). Functional Additives for Bakery Foods. Springer. p. 193. Retrieved 2009-08-12.

- ↑ Edwards, W.P. (2007). The Science of Bakery Products. Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 73. Retrieved 2009-08-12.

- 1 2 "The great Victoria sandwich". The Telegraph. Retrieved 25 February 2018

- ↑ "Development of Baking Powder". American Chemical Society. Retrieved 2016-01-27.

- ↑ "Baking Powder". Fine Cooking. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-06.

- 1 2 3 Savoie, Lauren (2015). "Taste Test: Baking Powder". Cook's Country (66): 31. ISSN 1552-1990.

- ↑ "Chocolate Cake with Vinegar - Antique Recipe Still Very Good". Cooks.com. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ↑ "All About Baking Powder". What's Cooking America. Archived from the original on 14 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ↑ Panko, Ben (20 June 2017). "The Great Uprising: How a Powder Revolutionized Baking". Smithsonian. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

Further reading

- Linda Civitello, Baking Powder Wars: The Cutthroat Food Fight that Revolutionized Cooking. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2017.

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

External links

- Cook's Thesaurus: Leavens Descriptions of various chemical leavening agents and substitutions.

- Baking Powder Contains list of aluminum-free baking powders available in the US.