Xylitol

| |

Xylitol crystals | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Systematic IUPAC name

(2R,3r,4S)-Pentane-1,2,3,4,5-pentol | |

| Other names

(2R,3r,4S)-Pentane-1,2,3,4,5-pentaol (not recommended) 1,2,3,4,5-Pentahydroxypentane Xylite | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.626 |

| E number | E967 (glazing agents, ...) |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C5H12O5 | |

| Molar mass | 152.15 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 1.52 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 92 to 96 °C (198 to 205 °F; 365 to 369 K) |

| Boiling point | 345.39 °C (653.70 °F; 618.54 K) Predicted value using Adapted Stein & Brown method[2] |

| ~100 g/L | |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Related compounds | |

Related alkanes |

Pentane |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

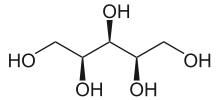

Xylitol /ˈzaɪlɪtɒl/ is a sugar alcohol used as a sweetener. The name derives from Ancient Greek: ξύλον, xyl[on], "wood" + suffix -itol, used to denote sugar alcohols. Xylitol is categorized as a polyalcohol or sugar alcohol (specifically an alditol). It has the formula CH2OH(CHOH)3CH2OH. It is a colorless or white solid that is soluble in water. Use of manufactured products containing xylitol may reduce tooth decay.[3]

Structure, production, occurrence

Unlike most sugar alcohols, xylitol is achiral.[4] Most other isomers of pentane-1,2,3,4,5-pentol are chiral, but xylitol has a plane of symmetry.

Industrial production starts from xylan, a hemicellulose, which is extracted from hardwoods[5] or corncobs. These polymers can be hydrolyzed into xylose, which are catalytically hydrogenated into xylitol. The conversion changes the sugar (xylose, an aldehyde) into a primary alcohol (xylitol).

Another method of producing xylitol is through microbial processes, including fermentative and biocatalytic processes in bacteria, fungi, and yeast cells, that take advantage of the xylose-intermediate fermentations to produce high yield of xylitol.[6] Common yeast cells used in effectively fermenting and producing xylitol are Candida tropicalis and Candida guilliermondii.[7]

Food properties

Xylitol is approved as a food additive in the United States.[8] One gram of xylitol contains 2.43 kilocalories (10.2 kilojoules),[9] or 63% of one gram of sugar (3.87 kcal (16.2 kJ).[10] Xylitol has a glycemic index of 7 (100 for glucose).[11] In some people, xylitol may cause gastrointestinal discomfort, including flatulence, diarrhea, and irritable bowel syndrome.[12] Subjects in one study consumed large monthly amounts of xylitol 1.5 kg (3.3 lb) over two years (maximum daily intake of over 400 g (14 oz), producing gastrointestinal symptoms in some people.[13]

Health aspects

Common products

Xylitol is used as an artificial sweetener in manufactured products, such as drugs or dietary supplements, confections, toothpaste, and chewing gum, but is not a common household sweetener.[3][14][15][16] Xylitol has negligible effects on blood sugar because it is metabolized independently of insulin.[15] Absorbed more slowly than sugar, xylitol supplies 40% fewer calories than table sugar.[15]

Dental care

Xylitol is a nonfermentable sugar alcohol[17][18] which may have advantages in dental care compared to other polyalcohols.[19][14] Two systematic reviews of clinical trials found no evidence that xylitol was superior to other polyols such as sorbitol[20] or equal to that of topical fluoride in its anticavity effect.[21] In the 33-month Xylitol for Adult Caries Trial, participants were given lozenges of either 5 g of xylitol or a sucralose-sweetened placebo. While this study initially found no statistically significant reduction in 33-month caries increment among adults at an elevated risk of developing cavities,[22] a further examination of data from this study revealed a significant reduction in the incidence of root caries in the group that received xylitol.[23]

In preliminary studies compared with chewing sucrose-sweetened gum, xylitol was associated with fewer cavities.[24] Cavity-causing bacteria prefer six-carbon sugars or disaccharides, while xylitol is nonfermentable and is not used as an energy source.[14] This same property renders it unsuitable for making bread, as it interferes with the ability of yeast to digest sugars.[14] The perception of sweetness obtained from consuming xylitol causes the secretion of saliva which acts as a buffer against the acidic environment created by the microorganisms in dental plaque. Increase in salivation can raise the pH to a neutral range within few minutes of xylitol consumption.[25]

A review of xylitol effects on dental cavities concluded that the body of evidence is of low to very low quality and is insufficient to determine whether any other xylitol-containing products can prevent cavities in infants, older children, or adults.[3]

Weight management

Processed foods containing xylitol as a non-nutritive sweetener may be useful to manage body weight.[16]

Toxicity

In humans

Xylitol has no known toxicity in humans; however, some report heart palpitations after consuming it. In one study, participants consumed a monthly average of 1.5 kg of xylitol with a maximum daily intake of 430 g with no apparent ill effects.[13] Like most sugar alcohols, xylitol has a laxative effect because sugar alcohols are not fully broken down during digestion; however, the effect varies from person to person. In one study of 13 children, four experienced diarrhea from xylitol's laxative effect when they ate more than 65 grams per day.[26] Studies have reported that adaptation occurs after several weeks of consumption.[26]

As with other sugar alcohols, with the exception of erythritol, consumption of xylitol in excess of one's "laxation threshold" (the amount of sweetener that can be consumed before abdominal discomfort occurs) can result in temporary gastrointestinal side effects, such as bloating, flatulence, and diarrhea. Adaptation (that is, an increase of the laxation threshold) occurs with regular intake. Xylitol has a lower laxation threshold than some sugar alcohols but is more easily tolerated than mannitol and sorbitol.[26][27]

In dogs

Xylitol is often fatal to dogs. According to the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Animal Poison Control Center, the number of cases of xylitol toxicosis in dogs has significantly increased since the first reports in 2002. Dogs that have eaten foods containing xylitol (greater than 100 mg/kilogram of bodyweight) have presented with low blood sugar (hypoglycemia), which can be life-threatening.[28] Low blood sugar can result in a loss of coordination, depression, collapse, and seizures in as little as 30 minutes.[29] Intake of doses of xylitol (greater than 500 to 1000 mg/kg bodyweight) has been implicated in liver failure in dogs, which can be fatal.[30]

In wild birds

Thirty Cape sugarbirds died within 30 minutes of drinking a solution made with xylitol from a feeder in a garden in Hermanus, South Africa. It is suspected to have triggered a massive insulin release, causing an irreversible drop in blood sugar.[31]

See also

References

- ↑ Safety data sheet for xylitol from Fisher Scientific. Retrieved 2014-11-02.

- ↑ "Xylitol". Chemspider. Retrieved 2015-05-13.

- 1 2 3 Riley P, Moore D, Ahmed F, Sharif MO, Worthington HV (2015). "Can xylitol used in products like sweets, candy, chewing gum and toothpaste help prevent tooth decay in children and adults?". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD010743. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010743.pub2.

- ↑ Wrolstad, Ronald E. (2012). Food Carbohydrate Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons. p. 176. ISBN 9780813826653. Retrieved 2012-10-20.

- ↑ Converti, Atillio; Parego, Patrizia; Domínguez, José Manuel (1999). "Xylitol Production from Hardwood Hemicellulose Hydrosylates" (PDF). Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 82: 141–151. doi:10.1385/abab:82:2:141.

- ↑ Nigam, Poonam; Singh, D. (1995). "Processes for Fermentative Production of Xylitol–a Sugar Substitute". Process Biochemistry. 30: 117–124. doi:10.1016/0032-9592(95)80001-8.

- ↑ Barbosa, M. F. S.; de Medeiros, M. B.; de Manchilha, I. M.; Schneider, H.; Lee, H. (1988). "Screening of yeasts for production of xylitol from D-xylose and some factors which affect xylitol yield in Candida guillermondii". Journal of Industrial Microbiology. 3: 241–251. doi:10.1007/bf01569582.

- ↑ "Xylitol; from Part 172, Food Additives Permitted for Direct Addition to Food for Human Consumption, Special Dietary and Nutritional Additives; Sec. 172.395". Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. United States Food and Drug Administration. 2012-04-01.

- ↑ Walters, D. Eric. "Xylitol". All About Sweeteners. Retrieved 2012-03-14.

- ↑ "Sugars, granulated (sucrose)". Self Nutrition Data. Retrieved 2012-03-14.

With a serving size of 100 grams, there are 387 calories

- ↑ Foster-Powell, Kaye; Holt, Susanna HA; Brand-Miller, Janette C (2002-01-01). "International table of glycemic index and glycemic load values". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 76 (1): 5–56. doi:10.1093/ajcn/76.1.5. Retrieved 2012-08-26.

- ↑ Mäkinen, Kauko (2016-10-20). "Gastrointestinal Disturbances Associated with the Consumption of Sugar Alcohols with Special Consideration of Xylitol: Scientific Review and Instructions for Dentists and Other Health-Care Professionals". International Journal of Dentistry. 2016: 5967907. doi:10.1155/2016/5967907. PMC 5093271. PMID 27840639.

- 1 2 Mäkinen, K. K. (1976). "Long-term tolerance of healthy human subjects to high amounts of xylitol and fructose: general and biochemical findings". Internationale Zeitschrift für Vitamin und Ernahrungsforschung Beiheft. 15: 92–104. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010743. PMID 783060.

- 1 2 3 4 Reusens, B. (2004). Remacle, Claude; Reusens, Brigitte, eds. Functional Foods, Ageing and Degenerative Disease. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-85573-725-9. Retrieved 2012-03-14.

- 1 2 3 "Xylitol". Drugs.com. 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- 1 2 "Artificial sweeteners and other sugar substitutes". Mayo Clinic. 20 August 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ↑ Edwardsson, Stig; Birkhed, Dowen; Mejàre, Bertil (1977). "Acid production from Lycasin, maltitol, sorbitol and xylitol by oral streptococci and lactobacilli". Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. 35 (5): 257–263. doi:10.3109/00016357709019801. PMID 21508.

- ↑ Drucker, D.B.; Verran, J. (1979). "Comparative effects of the substance-sweeteners glucose, sorbitol, sucrose, xylitol and trichlorosucrose on lowering of pH by two oral Streptococcus mutans strains in vitro". Archives of Oral Biology. 24 (12): 965–970. doi:10.1016/0003-9969(79)90224-3. PMID 44996.

- ↑ Maguire, A.; Rugg-Gunn, A. J. (2003). "Xylitol and caries prevention — is it a magic bullet?". British Dental Journal. 194 (8): 429–436. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4810022. PMID 12778091. Retrieved 2012-03-14.

- ↑ Mickenautsch, Steffen; Yengopal, Veerasamy (2012). "Effect of xylitol versus sorbitol: A quantitative systematic review of clinical trials". International Dental Journal. 62 (4): 175–188. doi:10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00113.x. PMID 23016999.

- ↑ Mickenautsch, Steffen; Yengopal, Veerasamy (2012). "Anticariogenic effect of xylitol versus fluoride – a quantitative systematic review of clinical trials". International Dental Journal. 62 (1): 6–20. doi:10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00086.x. PMID 22251032.

- ↑ Bader, James D.; et al. (2013). "Results from the Xylitol for Adult Caries Trial (X-ACT)". The Journal of the American Dental Association. 144 (1): 21–30. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0010. PMC 3926805.

- ↑ Ritter, A. V.; Bader, J. D.; Leo, M. C.; Preisser, J. S.; Shugars, D. A.; Vollmer, W. M.; Amaechi, B. T.; Holland, J. C. (2013). "Tooth-surface-specific Effects of Xylitol: Randomized Trial Results". Journal of Dental Research. 92 (6): 512–517. doi:10.1177/0022034513487211. PMC 3654758.

- ↑ "Policy on the Use of Xylitol in Caries Prevention" (PDF). Reference Manual. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. 33 (6): 42–44. 2010. Retrieved 2012-03-14.

- ↑ Scheinin, Arje (1993). "Dental Caries, Sugars and Xylitol". Annals of Medicine. 25: 519–521.

- 1 2 3 Wang, Yeu-Ming; van Eys, Jan (1981). "Nutritional significance of fructose and sugar alcohols". Annual Review of Nutrition. 1: 437–475. doi:10.1146/annurev.nu.01.070181.002253. PMID 6821187.

- ↑ "Sugar Alcohols" (PDF). Canadian Diabetes Association. 2005-05-01. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2012-03-14.

- ↑ Dunayer, Eric K.; Gwaltney-Brant, Sharon M. (2006). "Acute hepatic failure and coagulopathy associated with xylitol ingestion in eight dogs". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 229 (7): 1113–1117. doi:10.2460/javma.229.7.1113. PMID 17014359.

- ↑ Dunayer, Eric K. (2004). "Hypoglycemia following canine ingestion of xylitol-containing gum". Veterinary and Human Toxicology. 46 (2): 87–88. PMID 15080212.

- ↑ Dunayer, Eric K. (2006). "New findings on the effects of xylitol ingestion in dogs" (PDF). Veterinary Medicine. 101 (12): 791–797. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-17. Retrieved 2012-03-14.

- ↑ "Xylitol could kill sugarbirds – and pets". Independent Online. Retrieved 2015-07-12.

External links