Thai Forest Tradition

| |

| Type | Dharma Lineage |

|---|---|

| School | Theravada Buddhism |

| Formation | c. 1900 ; Isan, Thailand |

| Lineage Heads |

|

| Founding Maxims |

The customs of the noble ones (ariyavamsa) |

The Kammaṭṭhāna Forest Tradition of Thailand (Pali: kammaṭṭhāna; [kəmːəʈːʰaːna] meaning "place of work"), commonly known in the West as the Thai Forest Tradition, is a lineage of Theravada Buddhist monasticism, as well as the lineage's associated heritage of Buddhist praxis. The tradition is distinguished from other Buddhist traditions by its doctrinal emphasis of the notion that the mind precedes the world, its description of the Buddhist path as a training regimen for the mind, and its objective to reach proficiency in a diverse range of both meditative techniques and aspects of conduct that will eradicate defilements (Pali: "kilesas") – unwholesome aspects of the mind – in order to attain awakening.

The tradition began circa 1900 with Ajahn Mun Bhuridatto and Ajahn Sao Kantasīlo: two Dhammayut monks from the Lao-speaking cultural region of Northeast Thailand known as Isan. They began wandering the Thai countryside out of their desire to practice monasticism according to the normative standards of Classical Buddhism (which Ajahn Mun termed "the customs of the noble ones") during a time when folk religion was observed predominately among Theravada village monastic factions in the Siamese region. Because of this, orthopraxy with regard to the earliest extant Buddhist texts is emphasized in the tradition, and the tradition has a reputation for scrupulous observance of the Buddhist monastic code, known as the Vinaya.

Nevertheless, the Forest tradition is often cited as having an anti-textual stance, as Forest teachers in the lineage prefer edification through ad-hoc application of Buddhist practices rather than through methodology and comprehensive memorization, and likewise state that the true value of Buddhist teachings is in their ability to be applied to reduce or eradicate defilement from the mind. In the tradition's beginning the founders famously neglected to record their teachings, instead wandering the Thai countryside offering individual instruction to dedicated pupils. However, detailed meditation manuals and treatises on Buddhist doctrine emerged in the late 20th century from Ajahn Mun and Ajahn Sao's first-generation students as the Forest tradition's teachings began to propagate among the urbanities in Bangkok and subsequently take root in the West.

The purpose of practice in the tradition is to the ultimate end of experiencing the Deathless (Pali: amata-dhamma): an absolute, unconditioned dimension of the mind free of inconstancy, suffering, or a sense of self. According to the traditions exposition, awareness of the Deathless is boundless and unconditioned and cannot be conceptualized, so it must be arrived at through the aforementioned mental training which includes deep states of meditative concentration (Pali: jhana); and Forest teachers directly challenge the notion of dry insight.[1] The tradition further asserts that the training which leads to the Deathless is not undertaken simply through contentment or letting go, but the Deathless must be reached by "exertion and striving" (sometimes described as a "battle" or "struggle") to "cut" or "clear the path" through the "tangle" of defilements that bind the mind to the conditioned world in order to set awareness free.[2][3]

Related Forest Traditions are also found in other culturally similar Buddhist Asian countries, including the Galduwa Forest Tradition of Sri Lanka, the Taungpulu Forest Tradition of Myanmar and a related Lao Forest Tradition in Laos.[4][5][6]

| Thai Forest Tradition | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bhikkhus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sīladhārās | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related Articles | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Introduction and glossary

The mind

The mind (Pali: citta, mano — used interchangeably as “heart” or “mind” en masse), within the context of the Forest Tradition, refers to the most essential aspect of an individual that carries the responsibility of “taking on” or “knowing” mental preoccupations.

This characterization deviates from what is conventionally known in the West as “mind” — while the activities associated with thinking are often included when talking about the mind, they are considered mental processes separate from this essential knowing nature, which is sometimes termed the "primal nature of the mind".[7]

The primary quality attributed to the mind is that it is considered to be radiant, or luminous (Pali: “pabhassara”).[8] Teachers in the forest tradition assert that the mind is an immutable reality and that the mind is indestructible — that the mind simply “knows and does not die”.[9] The mind is also a fixed-phenomenon (Pali: "thiti-dhamma") — the mind itself does not “move” or follow out after its preoccupations, but rather receives them in place.[8] Since the mind as a phenomenon often eludes attempts to define it, the mind is often simply described in terms of its activities:

The mind isn’t “is” anything. What would it “is”? We’ve come up with the supposition that whatever receives preoccupations—good preoccupations, bad preoccupations, whatever—we call “heart” or “mind.” Like the owner of a house: Whoever receives the guests is the owner of the house. The guests can’t receive the owner. The owner has to stay put at home. When guests come to see him, he has to receive them. So who receives preoccupations? Who lets go of preoccupations? Who knows anything? [Laughs] That’s what we call “mind.” But we don’t understand it, so we talk, veering off course this way and that: “What is the mind? What is the heart?” We get things way too confused. Don’t analyze it so much. What is it that receives preoccupations? Some preoccupations don’t satisfy it, and so it doesn’t like them. Some preoccupations it likes and some it doesn’t. Who is that—who likes and doesn’t like? Is there something there? Yes. What’s it like? We don’t know. Understand? That thing... That thing is what we call the “mind.” Don’t go looking far away. [8]

— Ajaan Chah[10]

Defilements

While the mind doesn't follow out after its preoccupations, occasionally the mind will fall for its preoccupations while interacting with them, in which case the preoccupation can darken the mind. This darkness is termed defilement (Pali: “kilesa”), and when there is defilement in the mind, the mind can wrongly assume it is identical with its preoccupations.[11] Of the list of defilements; greed, aversion, and delusion are commonly identified as roots for the others.

If the defilements are considered entities, the associated mental processes are craving and clinging (Pali: “upadana”). The subsequent assumption on behalf of the mind that it is either identical with its preoccupations, or that its preoccupations belong to it, is part of a process called becoming in Buddhism.[12] Becoming is the process which leads to birth in any given lifetime. The earliest cause for both of these events which is identified in the texts is called avijja (Pali: ignorance, unawareness). [for more information, see twelve nidanas]

However, Ajaan Mun — the monk who began the forest tradition, reported that avijja is conditioned and therefore must arise from conditions, and that a mind imbued with delusion co-arises with avijja as its sustaining condition, and avijja can then in turn act as a sustaining factor for clinging and becoming. When beings are born, more karma may be created, which then acts as fuel for further fabrications and cravings. These processes therefore form feedback loops on one another — Ajaan Mun says: “In other words, these things will have to keep on arising and giving rise to each other continually. They are thus called sustained or sustaining conditions because they support and sustain one another.” [13] This assertion that the mind comes first was explained to Ajaan Mun's pupils in a talk, which was given in a style of wordplay derived from an Isan song-form known as maw lam:

The two elements, namo, [water and earth elements, i.e. the body] when mentioned by themselves, aren't adequate or complete. We have to rearrange the vowels and consonants as follows: Take the a from the n, and give it to the m; take the o from the m and give it to the n, and then put the ma in front of the no. This gives us mano, the heart. Now we have the body together with the heart, and this is enough to be used as the root foundation for the practice. Mano, the heart, is primal, the great foundation. Everything we do or say comes from the heart, as stated in the Buddha's words:

- mano-pubbangama dhamma

- mano-settha mano-maya:

'All dhammas are preceded by the heart, dominated by the heart, made from the heart.' The Buddha formulated the entire Dhamma and Vinaya from out of this great foundation, the heart. So when his disciples contemplate in accordance with the Dhamma and Vinaya until namo is perfectly clear, then mano lies at the end point of formulation. In other words, it lies beyond all formulations.

All supposings come from the heart. Each of us has his or her own load, which we carry as supposings and formulations in line with the currents of the flood (ogha), to the point where they give rise to unawareness (avijja), the factor that creates states of becoming and birth, all from our not being wise to these things, from our deludedly holding them all to be 'me' or 'mine'.[13]

The five aggregates and Nirvana

- still & at respite,

- quiet & clear.

No longer intoxicated,

no longer feverish,

its desires all uprooted,

its uncertainties shed,

its entanglement with the khandas

all ended & appeased,

the gears of the three levels of the cos-

mos all broken,

overweening desire thrown away,

its loves brought to an end,

with no more possessiveness,

all troubles cured

by Phra Ajaan Mun Bhuridatta, date unknown[14]

The Five Aggregates (Pali: “pañca khandha”, sometimes “khandas” for short) in Buddhism are a categorical model for phenomena as the mind comes into contact and relates to the world. The fivefold list describes the mind's experience of all mental and physical phenomena for any being in any mode of existence. The aggregates are forms (Pali: “rupa”), perceptions (“sanna”), feelings (“vedana”), fabrications (“sankhara”), and consciousness (“vinnana”).

Scholars in Bangkok at the time of Ajaan Mun stated that an individual is wholly composed of and defined by these Five Aggregates. However, the Pali Canon itself states that the aggregates are completely ended during the experience of Nirvana. This led to a problem attempting to draw a conclusion about the nature of Nirvana and whether there is experience of anything afterward.

Following from Ajaan Mun's reported insight that the mind precedes mental fashionings, Ajaan Mun further asserted that the mind sheds its attachments to its preoccupations yet is not itself annihilated during the Nirvana experience. The mind of one who has attained Nirvana (Pali: arahant, meaning “perfected person”) continues.

However it cannot be stated affirmatively where the mind of an arahant exists or that it exists at all, because describing an arahant's mind in terms of existence would limit it to the confines of time and space, which Nirvana occurs outside of. It would be equally incorrect to say that the mind of an arahant does not exist — the Buddha said that the idea of existence or non-existence “does not apply” to the behavior of an arahant's mind. Ajaan Mun argued all of this by describing a unique class of “objectless” or “themeless” consciousness specific to Nirvana, which differs from the consciousness aggregate.[15]

Kammatthana — The Place of Work

Kammatthana, (Pali: meaning “place of work”) refers to the whole of the practice with the goal of ultimately eradicating defilement from the mind:

The word “kammaṭṭhāna” has been well known among Buddhists for a long time and the accepted meaning is: “the place of work (or basis of work).” But the “work” here is a very important work and means the work of demolishing the world of birth (bhava); thus, demolishing (future) births, kilesas, taṇhā, and the removal and destruction of all avijjā from our hearts. All this is in order that we may be free from dukkha. In other words, free from birth, old age, pain and death, for these are the bridges that link us to the round of saṁsāra (vaṭṭa), which is never easy for any beings to go beyond and be free. This is the meaning of “work” in this context rather than any other meaning, such as work as is usually done in the world. The result that comes from putting this work into practice, even before reaching the final goal, is happiness in the present and in future lives. Therefore those [monks] who are interested and who practise these ways of Dhamma are usually known as Dhutanga Kammaṭṭhāna Bhikkhus, a title of respect given with sincerity by fellow Buddhists. — Ajaan Maha Bua[16]

The practice which monks in the tradition generally begin with are meditations on what Ajaan Mun called the five “root meditation themes”: the hair of the head, the hair of the body, the nails, the teeth, and the skin. One of the purposes of meditating on these externally visible aspects of the body is to counter the infatuation with the body, and to develop a sense of dispassion. Of the five, the skin is described as being especially significant. Ajaan Mun writes that “When we get infatuated with the human body, the skin is what we are infatuated with. When we conceive of the body as being beautiful and attractive, and develop love, desire, and longing for it, it's because of what we conceive of the skin.”[13]

However, the meditation practice in the forest tradition is not limited to these five themes. Many other themes are taught to be used to deal with certain situations, including but not limited to:

- The ten recollections: a list of ten meditation themes considered especially significant by the Buddha.

- The asubha contemplations: contemplations of foulness for combating sensual desire.

- The brahmaviharas: assertions of good-will for all beings to combat ill-will.

- The four satipatthana: frames of reference to get the mind into deep concentration

Mindfulness immersed in the body and Mindfulness of in-and-out breathing are both part of the ten recollections and the four satipatthana, and are commonly given special attention as primary themes for a meditator to focus on.

Pre-tradition Historical Background

The Dhammayut movement

Before authority was centralized in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the region known today as Thailand was a kingdom of semi-autonomous city states (Thai: mueang). These kingdoms were all ruled by a hereditary local governor, and while independent, paid tribute to Bangkok, the more powerful central city state in the region. (see History of Thailand) Each region had its own religious customs according to local tradition, and substantially different forms of Buddhism existed between mueangs. Though all of these local flavors of regional Thai Buddhism evolved their own customary elements relating to local spirit lore, all were shaped by the infusion of Mahayana Buddhism and Indian Tantric traditions, which arrived in the area prior to the fourteenth century. Additionally, many of the monastics in the villages engaged in behavior inconsistent the Buddhist monastic code (Pali: vinaya), including playing board games, and participating in boat races and waterfights.[17]

In the 1820s young Prince Mongkut, ordained as a Buddhist monk before rising to the throne later in his life, travelled around the Siamese region and quickly became dissatisfied with the caliber of Buddhist practice he saw around him. He was additionally concerned about the authenticity of the ordination lineages and the capacity of the monastic body to act as an agent that generates good karma (Pali: puññakkhettam, meaning "merit-field").

Mongkut dedicated his monastic career to reforming the monastic practice in Thailand. He did this in three ways:

- Mongkut searched neighboring regions for a lineage of monks with a stronger practice. Mongkut eventually found a higher caliber of monastic practice among the Mon people in the region. He reordained among this group.

- Mongkut searched for replacements of the classical Buddhist texts lost in the final siege of Ayutthaya. He eventually received copies of the Pali Canon as part of a missive to Sri Lanka.[18]

- When these texts finally arrived, Mongkut began a study group to promote understanding of Classical Buddhist principles.

These measures eventually culminated in the Dhammayut (Pali, meaning "in accordance with the Dharma") movement.

Mongkut's brother, who was king at the time, complained about Mongkut's involvement with the Mons — considering it improper for a member of the royal family to associate with an ethnic minority — and built a monastery on the outskirts of Bangkok. In 1836, Mongkut became the first abbot of Wat Bowonniwet Vihara, which would become the administrative center of the Thammayut order until the present day.[19][20]

The early participants of the movement continued to devote themselves to a combination of textual study and meditations they had discovered from the texts they had received. However, Thanissaro notes that none of the monks could make any claims of having successfully entered meditative concentration (Pali: samadhi), much less having reached a noble level.[18]

Ajaan Sao's monastery

The Dhammayut reform movement maintained strong footing as Mongkut later rose to the throne. Over the next several decades the Dhammayut monks would continue with their study and practice, however Thanissaro notes that none of the early Dhammayut monks could make claims to meditative attainments.

Ajaan Sao (1861–1941) was the older of the two monks who began the Kammatthana tradition using the backdrop of these Dhammayut reforms. Very little is known in the way of biographical details about Ajaan Sao's life,[21] however Ajaan Sao had a reputation as a Dhammayut monk for being uniquely focused solely on meditation, with less emphasis on Pali studies. In the late Nineteenth Century he was posted as abbot of Wat Liap, in Ubon. One of Ajaan Sao's students published a written reminiscence of Ajaan Sao's teaching style, which was based on the meditation mantra "buddho":

If the person asked, "What does 'Buddho' mean?" Ajaan Sao would answer, "Don't ask."

"What will happen after I've meditated on 'Buddho'?"

"Don't ask. Your only duty is simply to repeat the word 'Buddho' over and over in your mind."

That's how he taught: no long, drawn-out explanations.

If the student reported their progress to Ajaan Sao and it matched what Ajaan Sao was trying to teach, he would tell them to continue. If not, he would give them instructions specific to how he felt the student was off track:

Afterwards, he went and told Ajaan Sao, "When I meditated down to the point where the mind became calm and bright, it then went out, following the bright light. Visions of ghosts, divine beings, people, and animals appeared. Sometimes it seemed as if I went out following the visions."

As soon as Ajaan Sao heard this, he said, "This isn't right. For the mind to go knowing and seeing outside isn't right. You have to make it know inside."

The monk then asked, "How should I go about making it know inside?"

Phra Ajaan Sao answered, "When the mind is in a bright state like that, when it has forgotten or abandoned its repetition and is simply sitting empty and still, look for the breath. If the sensation of the breath appears in your awareness, focus on the breath as your object and then simply keep track of it, following it inward until the mind becomes even calmer and brighter."

The author goes on to say that Ajaan Sao would only give specific, practical instruction and would refrain from expounding sophisticated dharma topics: "This is one instance of how Phra Ajaan Sao taught his pupils — teaching just a little at a time, giving only the very heart of the practice, almost as if he would say, "Do this, and this, and this," with no explanations at all."[22]

Ajaan Mun's time at Wat Liap

Close to 10 years Ajaan Sao's junior, Ajaan Mun (1870-1949) went to Ajaan Sao's aforementioned monastery immediately after ordaining in 1893. Ajaan Mun's biographer records that during this time Ajaan Mun engaged in a meditation practice wherein one follows signs and counter-signs as awareness is directed away from the body. While in this state of calm-abiding, Ajaan Mun's mind would follow out of his body after visions, one after the other.[23]

After keeping at this practice of following visions for several months without satisfactory progress, Ajaan Mun turned away from it and resolved to keep his awareness in his body at all times.[23] Taking full sweeps of the body, investigating "from top to bottom, side to side, inside out and throughout; every body part and every aspect." Ajaan Mun's biographer reports that he "forced" his attention to traverse the parts of the body rather than reverting to its status-quo state of calm-abiding involving the signs and counter-signs. He did this mostly through a walking meditation practice, taking breaks to sit when his body was tired from walking.[24]

After keeping at this method of body contemplation for several days, Ajaan Mun sat down for an extended period, and subsequently discovered an entirely new state of calm-abiding based on this body contemplation practice. The biographer reports that "He knew with certainty that he had the correct method: for, when his citta ‘converged’ this time, his body appeared to be separated from himself." He made this practice his mainstay:

From then on, he continued to religiously practice body contemplation until he could attain a state of calm whenever he wanted. With persistence, he gradually became more and more skilled in this method, until the citta was firmly anchored in samãdhi. He had wasted three whole months chasing the disk and its illusions. But now, his mindfulness no longer abandoned him, and therefore, he was no longer adversely affected by the influences around him.[24]

Fifth-Reign reforms

During Ajaan Mun and Ajaan Sao's time together, massive consolidations in power were taking place in the Siamese region. Part of these shifts involved a cultural modernization of the entire region, which included an ongoing campaign to homogenize Buddhism among the villages. For these reforms, Chulalongkorn teamed up with his brother Prince Wachirayan.[25]

The spirit of Mongkut's reforms to find the noble attainments were abandoned as well. The fifth-reign reformers indirectly state that the noble attainments were no longer possible —In an introduction to the Buddhist monastic code written by Wachirayan, he stated that the rule forbidding monks to make claims to superior attainments was no longer relevant. [26] Chulalongkorn and Wachiraayan were taught by Western tutors and held distaste for the more mystical aspects of Buddhism:

Both Rama V and Prince Vajirañana were trained by European tutors, from whom they had absorbed Victorian attitudes toward rationality, the critical study of ancient texts, the perspective of secular history on the nature of religious institutions, and the pursuit of a “useful” past. As Prince Vajirañana stated in his Biography of the Buddha, ancient texts, such as the Pali Canon, are like mangosteens, with a sweet flesh and a bitter rind. The duty of critical scholarship was to extract the flesh and discard the rind. Norms of rationality were the guide to this extraction process. Teachings that were reasonable and useful to modern needs were accepted as the flesh. Stories of miracles and psychic powers were dismissed as part of the rind. [27]

Additionally during this time, the Thai government enacted legislation to group these factions into official monastic fraternities: the monks ordained as part of the Dhammayut reform movement were now part of the Dhammayut order, and all remaining regional monks were grouped together as the Mahanikai order.

Establishment period

The first long pilgrimage

Ajaan Mun and Ajaan Sao wandered the Northeast for a while. After a while, Ajaan Sao told Ajaan Mun that Ajaan Mun would need to continue on his own: while the tendency of Ajaan Sao's mind was "serene and peaceful", the temperament of Ajaan Mun's mind was "adventurous, and tending to go to extremes".[28][29] The biographer stated that Ajaan Mun informed his students of the added difficulty of attempting to practice without an adequate teacher.

At this point, even though Ajaan Mun had found what he considered the correct mode of samadhi practice, his mind still wanted to go out after visions:

Sometimes, he felt his body soaring high into the sky where he traveled around for many hours, looking at celestial mansions before coming back down. At other times, he burrowed deep beneath the earth to visit various regions in hell. There he felt profound pity for its unfortunate inhabitants, all experiencing the grievous consequences of their previous actions. Watching these events unfold, he often lost all perspective of the passage of time. In those days, he was still uncertain whether these scenes were real or imaginary. He said that it was only later on, when his spiritual faculties were more mature, that he was able to investigate these matters and understand clearly the definite moral and psychological causes underlying them.[29]

These openings to the celestial realms were spurred on by lapses in Ajaan Mun's concentration when mindfulness was lost. Ajaan Mun struggled with these lapses, "suffering considerable mental strain" trying different remedies through trial and error before eventually succeeding. The biographer writes that "Once he clearly understood the correct method of taming his dynamic mind, he found that it was versatile, energetic, and extremely quick in all circumstance."[29]

Ajaan Mun travelled on his own, first wandering the Northeast, then gradually heading towards the city center of Bangkok as his mind gained more inner stability. It was there he spent several months with a childhood friend named Chao Khun Upali as part of the rains period. Ajaan Mun consulted with Chao Khun Upali on practices pertaining to the development of Buddhist insight (Pali: paññā, meaning "wisdom" or "discernment"). He then left for an unspecified period, staying in caves in Lopburi, before returning to Bangkok one final time to consult with Chao Khun Upali, again pertaining to the practice of paññā.[30]

Feeling confident in his paññā practice he left for Sarika Cave — an area which was known to the locals for monks serially dying while or after staying there. During his stay there, Ajaan Mun suffered an intense ordeal where he was made critically ill for several days. After medicines failed to remedy his illness, Ajaan Mun ceased to take medication and resolved to rely on the power of his Buddhist practice. Ajaan Mun investigated the nature of the mind and this pain, until his illness disappeared, and successfully coped with visions featuring a club-wielding demon apparation who claimed he was the owner of the cave. According to forest tradition accounts, Ajaan Mun attained the noble level of non-returner (Pali: "anagami") after subduing this apparition and working through subsequent visions he encountered in the cave:[31]

Ajaan Mun's return to the Northeast

When Ajaan Mun returned from the forest following his time at Sarika Cave, his report of having reached a noble attainment was met with very mixed reaction among the Thai clergy. The ecclesiastical official Ven. Chao Khun Upali held him in high esteem — going as far as to praise one of his sermons as being delivered with muttodaya (a heart released). Ven. Upali's actions in vouching for Ajaan Mun before the ecclesiastical mainstream would be a significant factor in the subsequent leeway that state authorities gave to Ajaan Mun and his students.

At the other end of the spectrum was a student of Ven. Upali's commonly referred to as "Tisso Uan" (1867-1956), who later rose to Thailand's highest ecclesiastical rank of somdet. Tisso Uan thoroughly rejected claims to the authenticity of Ajaan Mun's attainment.[32]

Ajaan Mun's return to the Northeast to start teaching marked the effective beginning of the Kammatthana tradition. Ajaan Mun brought a set of radical ideas, many of which clashed with what scholars in Bangkok were saying at the time:

- Like Mongkut, Ajaan Mun stressed the importance of scrupulous observance of both the Buddhist monastic code (Pali: Vinaya). Ajaan Mun went further, and also stressed what are called the protocols: instructions for how a monk should go about daily activities such as keeping his hut, interacting with other people, etc.

Ajaan Mun also taught that virtue was a matter of the mind, and that intention forms the essence of virtue. This ran counter to what people in Bangkok said at the time, that virtue was a matter of ritual, and by conducting the proper ritual one gets good results.[33] - Ajaan Mun asserted that the practice of jhana was still possible even in modern times, and that meditative concentration was necessary on the Buddhist path. Ajaan Mun stated that one's meditation topic must be keeping in line with one's temperament — everyone is different, so the meditation method used should be different for everybody. Ajaan Mun said the meditation topic one chooses should be congenial and enthralling, but also give one a sense of unease and dispassion for ordinary living and the sensual pleasures of the world.[34]

- Ajaan Mun said that not only was the practice of jhana possible, but the experience of Nirvana was too. [35] He stated that Nirvana was characterized by a state of activityless consciousness, distinct from the consciousness aggregate.

To Ajaan Mun, reaching this mode of consciousness is the goal of the teaching — yet this consciousness transcends the teachings. Ajaan Mun asserted that the teachings are abandoned at the moment of Awakening, in opposition to the predominant scholarly position that Buddhist teachings are confirmed at the moment of Awakening. Along these lines, Ajaan Mun rejected the notion of an ultimate teaching, and argued that all teachings were conventional — no teaching carried a universal truth. Only the experience of Nirvana, as it is directly witnessed by the observer, is absolute.[36]

Acceptance and expansion period

Final acceptance in Bangkok

Tension between the forest tradition and the Thammayut administrative hierarchy escalated in 1926, when Tisso Uan attempted to drive a senior Forest Tradition monk named Ajaan Sing — along with his following of 50 monks and 100 nuns and laypeople — out of Ubon, which was under Tisso Uan's jurisdiction. Ajaan Sing refused, saying he and many of his supporters were born there, and they weren't doing anything to harm anyone. After arguing with district officials the directive was eventually dropped.[37]

In the late 1930s Tisso Uan formally recognized the Kammatthana monks as a faction. However, even after Ajaan Mun died in 1949, Tisso Uan continued to insist that Ajaan Mun had never been qualified to teach because he hadn't graduated from the government's formal Pali studies courses. With the passing of Ajaan Mun, Ajaan Thate Desaransi was designated the de facto head of the Forest Tradition (Thai: Ajaan Yai).

The relationship between the Thammayut ecclesia and the Kammaṭṭhāna monks changed in the 1950s. When Tisso Uan had become ill, Ajahn Lee went to teach meditation to him to help cope with his illness:

One day he said, "I never dreamed that sitting in samadhi would be so beneficial, but there's one thing that has me bothered. To make the mind still and bring it down to its basic resting level (bhavanga): Isn't this the essence of becoming and birth?"

"That's what samadhi is," I told him, "becoming and birth."

"But the Dhamma we're taught to practice is for the sake of doing away with becoming and birth. So what are we doing giving rise to more becoming and birth?"

"If you don't make the mind take on becoming, it won't give rise to knowledge, because knowledge has to come from becoming if it's going to do away with becoming. This is becoming on a small scale — uppatika bhava — which lasts for a single mental moment. The same holds true with birth. To make the mind still so that samadhi arises for a long mental moment is birth. Say we sit in concentration for a long time until the mind gives rise to the five factors of jhana: That's birth. If you don't do this with your mind, it won't give rise to any knowledge of its own. And when knowledge can't arise, how will you be able to let go of unawareness [avijja]? It'd be very hard.

"As I see it," I went on, "most students of the Dhamma really misconstrue things. Whatever comes springing up, they try to cut it down and wipe it out. To me, this seems wrong. It's like people who eat eggs. Some people don't know what a chicken is like: This is unawareness. As soon as they get hold of an egg, they crack it open and eat it. But say they know how to incubate eggs. They get ten eggs, eat five of them and incubate the rest. While the eggs are incubating, that's "becoming." When the baby chicks come out of their shells, that's "birth." If all five chicks survive, then as the years pass it seems to me that the person who once had to buy eggs will start benefiting from his chickens. He'll have eggs to eat without having to pay for them, and if he has more than he can eat he can set himself up in business, selling them. In the end he'll be able to release himself from poverty.

"So it is with practicing samadhi: If you're going to release yourself from becoming, you first have to go live in becoming. If you're going to release yourself from birth, you'll have to know all about your own birth."[38]

Tisso Uan eventually recovered, and a friendship between Tisso Uan and Ajaan Lee began that would cause Tisso Uan to reverse his opinion of the Kammaṭṭhāna tradition. Tisso Uan said to Ajaan Lee: "People who study and practice the Dhamma get caught up on nothing more than their own opinions, which is why they never get anywhere. If everyone understood things correctly, there wouldn’t be anything impossible about practicing the Dhamma."

Tisso Uan then invited Ajahn Lee to teach in the city. This event marked a turning point in relations between the Dhammayut administration and the Forest Tradition, and interest continued to grow as a friend of Ajaan Maha Bua's named Nyanasamvara rose to the level of somdet, and later the Sangharaja of Thailand. Additionally, the clergy who had been drafted as teachers from the Fifth Reign onwards were now being displaced by civilian teaching staff, which left the Dhammayut monks with a crisis of identity.[39][40]

At this time, the Thai Royal Family was not yet interested in meditation. When Ajaan Lee finally left Bangkok, he said eventually the royals would be interested in meditation, and a forest monk would come back at that time to teach.

Recording of forest doctrine

During Ajaan Mun's life, he said to Ajaan Lee that Ajaan Lee would have to write down and codify the teachings of the forest tradition. Later in Ajaan Lee's career, he wrote several books which recorded the doctrinal positions of the forest tradition, and explained broader Buddhist concepts in the Forest Tradition's terms. Ajaan Lee emphasized his metaphor of Buddhist practice as a skill, and reintroduced the Buddha's idea of skillfulness — acting in ways that emerge from having trained the mind and heart.

Ajaan Lee said that good and evil both exist naturally in the world, and that the skill of the practice is ferreting out good and evil, or skillfulness from unskillfulness. The idea of "skill" refers to a distinction in Asian countries between what is called warrior-knowledge (skills and techniques) and scribe-knowledge (ideas and concepts). Ajaan Lee brought some of his own unique perspectives to Forest Tradition teachings:

- Ajaan Lee reaffirmed that meditative concentration (samadhi) was necessary, yet further distinguished between right concentration and various forms of what he called wrong concentration — techniques where the meditator follows awareness out of the body after visions, or forces awareness down to a single point were considered by Ajaan Lee as off-track.[41]

- Ajaan Lee stated that discernment (panna) was mostly a matter of trial-and-error. He used the metaphor of basket-weaving to describe this concept: you learn from your teacher, and from books, basically how a basket is supposed to look, and then you use trial-and-error to produce a basket that is in line with what you have been taught about how baskets should be. These teachings from Ajaan Lee correspond to the factors of the first jhana known as directed-thought (Pali: "vitakka"), and evaluation (Pali: "vicara").[42]

- Ajaan Lee said that the qualities of virtue that are worked on correspond to the qualities that need to be developed in concentration. Ajaan Lee would say things like "don't kill off your good mental qualities", or "don't steal the bad mental qualities of others", relating the qualities of virtue to mental qualities in one's meditation.[43]

Additionally, Ajaan Lee pioneered two unique approaches to breath meditation wherein one focuses on the subtle energies in the body, which Ajaan Lee termed breath energies. For these and other reasons, Ajaan Lee and his students are considered a distinguishable sub-lineage that is sometimes referred to as the "Chanthaburi Line".

Forest monasteries in the West

Ajahn Chah was unique among in the Forest Tradition in that he was not a Dhammayut monk but rather a Mahanikai monk. He only spent one weekend with Ajaan Mun, however he had teachers within the Mahanikai who had more exposure to Ajaan Mun. His connection to the Forest Tradition was publicly recognized by Ajaan Maha Bua. The community that he founded is formally referred to as The Forest Tradition of Ajahn Chah.

In 1967, Ajahn Chah founded Wat Pah Pong. That same year, an American monk from another monastery, Venerable Sumedho (later Ajahn Sumedho) came to stay with Ajahn Chah at Wat Pah Pong. He found out about the monastery from one of Ajahn Chah's existing monks who happened to speak "a little bit of english".[44] In 1975, Ajahns Chah and Sumedho founded Wat Pah Nanachat, an international forest monastery in Ubon Ratchatani which offers services in English.

In the 1980s the Forest Tradition of Ajahn Chah expanded to the West with the founding of Amaravati Buddhist Monastery in the UK. Ajahn Chah stated that the spread of Communism in Southeast Asia motivated him to establish the Forest Tradition in the West.

The Forest Tradition of Ajahn Chah has since expanded to cover Canada, Germany, Italy, New Zealand, and the United States.[45]

Routinization period

Royal patronage and instruction to the elite

The aforementioned monk that Ajaan Lee predicted would arrive to instruct the royal family on meditation turned out to be Ajaan Maha Bua. He was introduced to the Queen and King by Somdet Nyanasamvara Suvaddhano (Charoen Khachawat).

Ajaan Mun and Ajaan Lee would describe obstacles that commonly occurred in meditation but would not explain how to get through them, forcing students to come up with solutions on their own. Additionally, they were generally very private about their own meditative attainments.

Ajaan Maha Bua, on the other hand, saw what he considered to be a lot of strange ideas being taught about meditation in Bangkok in the later decades of the 20th century. For that reason Ajaan Maha Bua decided to vividly describe how each noble attainment is reached, even though doing so indirectly revealed that he was confident he had attained a noble level. Though the Vinaya prohibits a monk from directly revealing ones own or another's attainments to laypeople while that person is still alive, Ajaan Maha Bua wrote in Ajaan Mun's posthumous biography that he was convinced that Ajaan Mun was an arahant. Thanissaro Bhikkhu remarks that this was a significant change of the teaching etiquette within the Forest Tradition.[46]

- Ajaan Maha Bua's primary metaphor for Buddhist practice was that it was a battle against the defilements. Just as soldiers might invent ways to win battles that aren't found in military history texts, one might invent ways to subdue defilement. Whatever technique one could come up with — whether it was taught by one's teacher, found in the Buddhist texts, or made up on the spot — if it helped with a victory over the defilements, it counted as a legitimate Buddhist practice. [47]

- Ajaan Maha Bua is widely known for his teachings on dealing with physical pain. For a period, Ajaan Maha Bua had a student who was dying of cancer, and Ajaan Maha Bua gave a series on talks surrounding the perceptions that people have that create mental problems surrounding the pain. Ajaan Maha Bua said that these incorrect perceptions can be changed by posing questions about the pain in the mind. (i.e. "what color is the pain? does the pain have bad intentions to you?" "Is the pain the same thing as the body? What about the mind?")[48]

- There was a widely publicized incident in Thailand where monks in the North of Thailand were publicly stating that Nirvana is the true self, and scholar monks in Bangkok were stating that Nirvana is not-self. (see: Dhammakaya Movement)

At one point, Ajaan Maha Bua was asked whether Nirvana was self or not-self and he replied "Nirvana is Nirvana, it is neither self nor not-self". Ajaan Maha Bua stated that not-self is merely a perception that is used to pry one away from infatuation with the concept of a self, and that once this infatuation is gone the idea of not-self must be dropped as well.[49]

Forest closure and Thai politics

With the passing of Ajaan Thate in 1994, Ajaan Maha Bua was designated the new Ajaan Yai.

In recent times, the Forest Tradition has undergone a crisis surrounding the destruction of forests in Thailand. Since the Forest Tradition had gained significant pull from the royal and elite support in Bangkok, the Thai Forestry Bureau decided to deed large tracts of forested land to Forest Monasteries, knowing that the forest monks would preserve the land as a habitat for Buddhist practice. The land surrounding these monasteries have been described as "forest islands" surrounded by barren clear-cut area.

By this time, the Forest Tradition's authority had been fully routinized. By the 1990s Ajaan Maha Bua had grown a following of influential conservative-loyalist Bangkok elites.[50]

In the midst of the Thai Financial crisis in the late 1990s, Ajaan Maha Bua initiated Save Thai Nation — a campaign which aimed to raise capital to underwrite the Thai currency. By the year 2000, 3.097 tonnes of gold was collected. By the time of Ajaan Maha Bua's death, an estimated 12 tonnes of gold had been collected, valued at approximated 500 million USD. 10.2 million dollars of foreign exchange was also donated to the campaign. All proceeds were handed over to the Thai central bank to back the Thai Baht.[50]

The Thai administration under Prime Minister Chuan Leekpai attempted to thwart the Save Thai Nation campaign in the late 1990s. This led to Ajaan Maha Bua's striking back with heavy criticism, which is cited as a contributing factor to the ousting of Chuan Leekpai and the election of Thaksin Shinawatra as prime minister in 2001. Thanissaro Bhikkhu notes that the Dhammayut hierarchy, seeing the political influence that Ajaan Maha Bua could wield, felt threatened and began to take action. Thanissaro wrote in 2005:

The Mahanikaya hierarchy, which had long been antipathetic to the Forest monks, convinced the Dhammayut hierarchy that their future survival lay in joining forces against the Forest monks, and against Ajaan Mahabua in particular. Thus the last few years have witnessed a series of standoffs between the Bangkok hierarchy and the Forest monks led by Ajaan Mahabua, in which government-run media have personally attacked Ajaan Mahabua. The hierarchy has also proposed a series of laws—a Sangha Administration Act, a land-reform bill, and a “special economy” act—that would have closed many of the Forest monasteries, stripped the remaining Forest monasteries of their wilderness lands, or made it legal for monasteries to sell their lands. These laws would have brought about the effective end of the Forest tradition, at the same time preventing the resurgence of any other forest tradition in the future. So far, none of these proposals have become law, but the issues separating the Forest monks from the hierarchy are far from settled.[39]

In the late 2000s bankers at the Thai central bank attempted to consolidate the bank's assets and move the proceeds from the Save Thai Nation campaign into the banks into the ordinary accounts which discretionary spending comes out of. The bankers received pressure from Ajaan Maha Bua's supporters which effectively prevented them from doing this. On the subject, Ajaan Maha Bua said that "it is clear that combining the accounts is like tying the necks of all Thais together and throwing them into the sea; the same as turning the land of the nation upside down."[50]

Throughout the 2000s, Ajaan Maha Bua was accused of political leanings — first from Chuan Leekpai supporters, and then receiving criticism from the other side after his vehement condemnations of Thaksin Shinawatra. On being accused of aspiring to political ambitions, Ajaan Maha Bua replied:

If someone squanders the nation's treasure ... what do you think this is? People should fight against this kind of stealing. Don't be afraid of becoming political, because the nation's heart (hua-jai) is there (within the treasury). The issue is bigger than politics. This is not to destroy the nation. There are many kinds of enemies. When boxers fight do they think about politics? No. They only think about winning. This is Dhamma straight. Take Dhamma as first principle.[51]

In addition to Ajaan Maha Bua's activism for Thailand's economy, his monastery is estimated to have donated some 600 million Baht (19 million USD) to charitable causes.[52]

Ajaan Maha Bua was the last of Ajaan Mun's prominent first-generation students. He died in 2011. In his will he requested that all of the donations from his funeral be converted to gold and donated to the Central Bank — an additional 330 million Baht and 78 kilograms of gold.[53][54]

Other practices

Daily Routine

Morning and Evening Chanting

All Thai monasteries generally have a morning and evening chant, which usually takes an hour long for each, and each morning and evening chant may be followed by a meditation session, usually around an hour as well.

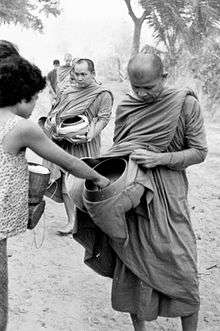

Morning Alms Round

At Thai monasteries the monks will go for alms early in the morning, sometimes around 6:00 AM, although monasteries such as Wat Pah Nanachat and Wat Mettavanaram start around 8:00 AM and 8:30 AM, respectively. At Dhammayut monasteries (and some Maha Nikaya forest monasteries, including Wat Pah Nanachat), monks will eat just one meal per day. For young children it is customary for the parent to help them scoop food into monks bowls.[55]

Anumodana

At Dhammayut monasteries, anumodana (Pali, rejoicing together) is a chant performed by the monks after a meal to recognize the mornings offerings, as well as the monks' approval for the lay people's choice of generating merit (Pali: puñña) by their generosity towards the Sangha. Among the thirteen verses to the Anumodana chant, three stanzas are chanted as part of every Anumodana, as follows:

1. (LEADER):

- Yathā vārivahā pūrā

- Paripūrenti sāgaraṃ

- Evameva ito dinnaṃ

- Petānaṃ upakappati

- Icchitaṃ patthitaṃ tumhaṃ

- Khippameva samijjhatu

- Sabbe pūrentu saṃkappā

- Cando paṇṇaraso yathā

- Mani jotiraso yathā.

- Just as rivers full of water fill the ocean full,

- Even so does that here given

- benefit the dead (the hungry shades).

- May whatever you wish or want quickly come to be,

- May all your aspirations be fulfilled,

- as the moon on the fifteenth (full moon) day,

- or as a radiant, bright gem.

2. (ALL):

- Sabbītiyo vivajjantu

- Sabba-rogo vinassatu

- Mā te bhavatvantarāyo

- Sukhī dīghāyuko bhava

- Abhivādana-sīlissa

- Niccaṃ vuḍḍhāpacāyino

- Cattāro dhammā vaḍḍhanti

- Āyu vaṇṇo sukhaṃ balaṃ.

- May all distresses be averted,

- may every disease be destroyed,

- May there be no dangers for you,

- May you be happy & live long.

- For one of respectful nature who

- constantly honors the worthy,

- Four qualities increase:

- long life, beauty, happiness, strength.

3.

Dhutanga

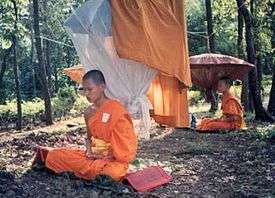

Dhutanga (meaning austere practice Thai: Tudong) is a word generally used in the commentaries to refer to the thirteen ascetic practices. In Thai Buddhism it has been adapted to refer to extended periods of wandering in the countryside, where monks will take one or more of these ascetic practices. During these periods monks will live off of whatever is given to them by laypersons they encounter during the trip, and sleep wherever they can. Sometimes monks will bring a large umbrella-tent with attached mosquito netting known as a crot (also spelled krot, clot, or klod). The crot will usually have a hook on the top so it may be hung on a line tied between two trees.

Vassa (Rains Retreat)

Vassa (in Thai, phansa), is a period of retreat for monastics during the rainy season (from July to October in Thailand). Many young Thai men traditionally ordain for this period, before disrobing and returning to lay life.

Precepts and Ordination

There are several precept levels: Five Precepts, Eight Precepts, Ten Precepts and the patimokkha. The Five Precepts (Pañcaśīla in Sanskrit and Pañcasīla in Pāli) are practiced by laypeople, either for a given period of time or for a lifetime. The Eight Precepts are a more rigorous practice for laypeople. Ten Precepts are the training-rules for sāmaṇeras and sāmaṇerīs (novitiate monks and nuns). The Patimokkha is the basic Theravada code of monastic discipline, consisting of 227 rules for bhikkhus and 311 for nuns bhikkhunis (nuns).

Temporary or short-term ordination is so common in Thailand that men who have never been ordained are sometimes referred to as "unfinished." Long-term or lifetime ordination is deeply respected. The ordination process usually begins as an anagarika, in white robes.

Customs

Monks in the tradition are typically addressed as "Venerable", alternatively with the Thai Ayya or Taan (for men). Any monk may be addressed as "bhante" regardless of seniority. For Sangha elders who have made a significant contribution to their tradition or order, the title Luang Por (Thai: Venerable Father) may be used.

According to The Isaan: "In Thai culture, it is considered impolite to point the feet toward a monk or a statue in the shrine room of a monastery." In Thailand monks are usually greeted by lay people with the wai gesture, though, according to Thai custom, monks are not supposed to wai laypeople. When making offerings to the monks, it is best not to stand while offering something to a monk who is sitting down.

Notes

^ Khatha Akhom (Thai: คา-ถา-อา-คม, Lao: ຄາຖາອາຄົມ, IPA: [kʰaːtʰǎːʔaːkʰom]) – translated as witchcraft, or Wicha Akhom (Thai: วิชา อาคม, IPA: [wíʔtɕʰaːʔaːkʰom]). Components are as follows:

- Akhom literally means magic, spell, charm.

- Khatha literally means incantation (from Pali: Gatha, meaning verse, as in a verse of the Pali Canon)

- Wicha (from Pali: vijja) literally means study, knowledge, branch of study

References

- ↑ Lopez 2016, p. 61.

- ↑ Robinson, Johnson & Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu 2005, p. 167.

- ↑ Taylor 1993, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ http://www.hermitary.com/articles/thudong.html

- ↑ http://www.buddhanet.net/pdf_file/Monasteries-Meditation-Sri-Lanka2013.pdf

- ↑ http://www.nippapanca.org/

- ↑ Lee, 2010 & p. 19.

- 1 2 Lee, 2010 & p.19.

- ↑ Maha Bua 2010.

- ↑ Chah 2013.

- ↑ Maha Bua 2005.

- ↑ Thanissaro, 2013 & p. 9.

- 1 2 3 Mun 2016.

- ↑ Mun 2015.

- ↑ Thanissaro 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1S40nS_0R9Y&t=2680s.

- ↑ Maha Bua, 2010 & P. 1.

- ↑ Tiyavanich, 1993 & p. 2-6.

- 1 2 Thanissaro 2010.

- ↑ Lopez 2013, p. 696.

- ↑ Tambiah 1984, p. 156.

- ↑ Tambiah.

- ↑ Phut Thaniyo 2013.

- 1 2 Tambiah, 1984 & p. 84.

- 1 2 Maha Bua 2014.

- ↑ Taylor & p. 62.

- ↑ Taylor & p. 141.

- ↑ Thanissaro, 2005 & p. 11).

- ↑ Tambiah & p. 84.

- 1 2 3 Maha Bua 2004.

- ↑ Tambiah & p. 86-87.

- ↑ Tambiah, 1984 & p. 87-88.

- ↑ Thanissaro 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1S40nS_0R9Y&t=2880s.

- ↑ Thanissaro 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1S40nS_0R9Y&t=2070s.

- ↑ Thanissaro 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1S40nS_0R9Y&t=2460s.

- ↑ Thanissaro 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1S40nS_0R9Y&t=2670s.

- ↑ Thanissaro 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1S40nS_0R9Y&t=2760s.

- ↑ Taylor 1993, p. 137.

- ↑ Lee 2012.

- 1 2 Thanissaro 2005.

- ↑ Taylor & p. 139.

- ↑ Lee 2012, p. 60, http://www.dhammatalks.org/Archive/Writings/BasicThemes(four_treatises)_121021.pdf.

- ↑ Thanissaro 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1S40nS_0R9Y&t=3060s.

- ↑ Thanissaro 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1S40nS_0R9Y&t=3120s.

- ↑ ajahnchah.org.

- ↑ Harvey, 2013 & p. 443.

- ↑ Thanissaro 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1S40nS_0R9Y&t=4200s.

- ↑ Thanissaro 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1S40nS_0R9Y&t=4260s.

- ↑ Thanissaro 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1S40nS_0R9Y&t=4320s.

- ↑ Thanissaro 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1S40nS_0R9Y&t=4545s.

- 1 2 3 Taylor 2008, p. 118–128.

- ↑ Taylor 2008, p. 123.

- ↑ Taylor 2008, p. 126-127.

- ↑ [[#CITEREF|]].

- ↑ https://www.thaivisa.com/forum/topic/448638-nirvana-funeral-of-revered-thai-monk.

- ↑ Thanissaro 2003.

Bibliography

A – C

- Abhayagiri Foundation (2015), Origins of Abhayagiri

- Access to Insight (2013), Theravada Buddhism: A Chronology, Access to Insight

- Bruce, Robert (1969). "King Mongkut of Siam and his Treaty with Britain". Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch. 9: 88–100. JSTOR 23881479.

- Bodhisaddha Forest Monastery, The Ajahn Chah lineage: spreading Dhamma to the West

- Buswell, Robert; Lopez, Donald S. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15786-3.

- Chah, Ajahn (2013), Still Flowing Water: Eight Dhamma Talks (PDF), Abhayagiri Foundation , translated from Thai by Thanissaro Bhikkhu.

- Chah, Ajahn (2010), Not for Sure: Two Dhamma Talks, Abhayagiri Foundation , translated from Thai by Thanissaro Bhikkhu.

- Ajahn Chah (2006). A Taste of Freedom: Selected Dhamma Talks. Buddhist Publication Society. ISBN 978-955-24-0033-9.

D – I

- Harvey, Peter (2013), An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices, Cambridge University Press

- "Rattanakosin Period (1782 -present)". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- Gundzik, Jephraim (2004), Thaksin's populist economics buoy Thailand, Asia Times

K – P

- Lee Dhammadaro, Ajahn (2012), Basic Themes (PDF), Dhammatalks.org

- Lee Dhammadaro, Ajahn (2000), Keeping the Breath in Mind and Lessons in Samadhi, Access to Insight

- Lee Dhammadaro, Ajahn (2011), Frames of Reference (PDF), Dhammatalks.org

- Lee Dhammadaro, Ajahn (2012), The Autobiography of Phra Ajaan Lee (PDF), Dhammatalks.org

- Lopez, Alan Robert (2016), Buddhist Revivalist Movements: Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement, Palgrave Macmillan US

- Maha Bua Nyanasampanno, Ajahn (2005), Arahattamagga, Arahattaphala: the Path to Arahantship – A Compilation of Venerable Acariya Maha Boowa’s Dhamma Talks about His Path of Practice (PDF), Forest Dhamma Books

- Maha Bua Nyanasampanno, Ajahn (2004), Venerable Ācariya Mun Bhuridatta Thera: A Spiritual Biography, Forest Dhamma Books

- Maha Bua Nyanasampanno, Ajahn (2010), Patipada: Venerable Acariya Mun's Path of Practice, Wisdom Library

- McDaniel, Justin Thomas (2011), The Lovelorn Ghost and the Magical Monk: Practicing Buddhism in Modern Thailand, Columbia University Press

- Mun Bhuridatta, Ajahn (2016), A Heart Released (PDF), Dhammatalks.org

- Orloff, Rich (2004), "Being a Monk: A Conversation with Thanissaro Bhikkhu", Oberlin Alumni Magazine, 99 (4)

- Pali Text Society, The (2015), The Pali Text Society's Pali-English Dictionary

- Piker, Steven (1975), "Modernizing Implications of 19th Century Reforms in the Thai Sangha", Contributions to Asian Studies, Volume 8: The Psychological Study of Theravada Societies, E.J. Brill

- Phut Thaniyo, Ajaan (2013), Ajaan Sao's Teaching: A Reminiscence of Phra Ajaan Sao Kantasilo, Access to Insight (Legacy Edition)

Q – S

- Quli, Natalie, Multiple Buddhist Modernisms: Jhana in Convert Theravada (PDF)

- Robinson, Richard H.; Johnson, Willard L.; Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu (2005). Buddhist Religions: A Historical Introduction. Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. ISBN 978-0-534-55858-1.

- Schuler, Barbara (2014). Environmental and Climate Change in South and Southeast Asia: How are Local Cultures Coping?. Brill.

- Scott, Jamie (2012), The Religions of Canadians, University of Toronto Press

- Sujato (2008), Original Mind Controversy

- Sumedho, Ajahn (2007), Thirty years from Hampstead (interview), The Forest Sangha Newsletter

T

- Tambiah, Stanley Jeyaraja (1984). The Buddhist Saints of the Forest and the Cult of Amulets. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27787-7.

- Taylor, J. L. (1993). Forest Monks and the Nation-state: An Anthropological and Historical Study in Northeastern Thailand. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-3016-49-1.

- Taylor, Jim [J.L.] (2008), Buddhism and Postmodern Imaginings in Thailand: The Religiosity of Urban Space, Ashgate

- Thanissaro (2010), The Customs of the Noble Ones, Access To Insight

- Thanissaro (2006), The Traditions of the Noble Ones (PDF), dhammatalks.org

- Thanissaro (2006), Legends of Somdet Toh, Access to Insight

- Thanissaro (2011), Wings to Awakening, Access to Insight

- Thanissaro (2013), With Each and Every Breath, Access to Insight

- Thanissaro (2005), Jhana Not by the Numbers, Access to Insight

- Thanissaro (2015), Wilderness Wisdom, The Distinctive Teachings of the Thai Forest Tradition, University of the West

- Thate Desaransi, Ajahn (1994), Buddho, Access to Insight

- Tiyavanich, Kamala (January 1997). Forest Recollections: Wandering Monks in Twentieth-Century Thailand. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1781-7.

Z

- Zhi Yun Cai (Fall 2014), Doctrinal Analysis of the Origin and Evolution of the Thai Kammatthana Tradition with a Special Reference to the Present Kammatthana Ajahns, University of the West

External links

Monasteries

About the Tradition

- Significant figures with published and translated dhamma books — Access to Insight

- An essay on the origins of the Thai Forest Tradition by Thanissaro Bhikkhu

- Page about the forest tradition from Vimutti Buddhist monastery in New Zealand

- About the Forest Tradition — Abhayagiri.org

- Book by Ajahn Maha Bua about Kammatthana practice

Dhamma Resources

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu's translations and dhamma talks

- Resources on the Ajahn Chah Tradition

- Books translated by Ajahn Dick Silaratano, Ajahn Suchard Abhijato, Ajahn Pannavaddho, and Thanissaro Bhikkhu