Books of Chronicles

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tanakh (Judaism) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old Testament (Christianity) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bible portal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the Christian Bible, the two Books of Chronicles (commonly referred to as 1 Chronicles and 2 Chronicles, or First Chronicles and Second Chronicles) generally follow the two Books of Kings and precede Ezra–Nehemiah, thus concluding the history-oriented books of the Old Testament,[1] often referred to as the Deuteronomistic history.

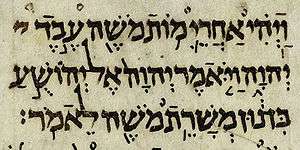

In the Hebrew Bible, Chronicles is a single book, called Diḇrê Hayyāmîm (Hebrew: דִּבְרֵי־הַיָּמִים, "The Matters [of] the Days"), and is the final book of Ketuvim, the third and last part of the Tanakh. Chronicles was divided into two books in the Septuagint and called I and II Paralipoménōn (Greek: Παραλειπομένων, "things left on one side").[2] The English name comes from the Latin name chronikon, which was given to the text by scholar Jerome in the 5th century.

Chronicles present the biblical narrative from the first human being, Adam, through the history of ancient Judah and Israel until the proclamation of King Cyrus the Great (c. 540 BC).

Summary

The Chronicles narrative begins with Adam and the story is then carried forward, almost entirely by genealogical lists, down to the founding of the first Kingdom of Israel (1 Chronicles 1–9). The bulk of the remainder of 1 Chronicles, after a brief account of Saul, is concerned with the reign of David (1 Chronicles 11–29). The next long section concerns David's son Solomon (2 Chronicles 1–9), and the final part is concerned with the Kingdom of Judah with occasional references to the second kingdom of Israel (2 Chronicles 10–36). In the last chapter Judah is destroyed and the people taken into exile in Babylon, and in the final verses the Persian king Cyrus the Great conquers the Neo-Babylonian Empire, and authorises the restoration of the Temple in Jerusalem, and the return of the exiles.[3]

Structure

Originally a single work, Chronicles was divided into two in the Septuagint, a Greek translation produced in the 3rd and 2nd centuries Before Christ.[4] It has three broad divisions: (1) the genealogies in chapters 1–9 of 1 Chronicles; (2) the reigns of David and Solomon, taking up the remainder of 1 Chronicles and chapters 1–9 of 2 Chronicles; and (3) the story of the divided kingdom, the remainder of 2 Chronicles.

Within this broad structure there are signs that the author has used various other devices to structure his work, notably the drawing of parallels between David and Solomon (the first becomes king, establishes the worship of Israel's God in Jerusalem, and fights the wars that will enable the Temple to be built, then Solomon becomes king, builds and dedicates the Temple, and reaps the benefits of prosperity and peace).[5]

Composition

Origins

The last events in Chronicles take place in the reign of Cyrus the Great, the Persian king who conquered Babylon in 539 BC; this sets an earliest possible date for the book. It was probably composed between 400–250 BC, with the period 350–300 BC the most likely.[5] The latest person mentioned in Chronicles is Anani, an eighth-generation descendant of King Jehoiachin according to the Masoretic Text. Anani's birth would likely have been sometime between 425 and 400 BC.[6] The Septuagint gives an additional five generations in the genealogy of Anani. For those scholars who side with the Septuagint's reading, Anani's likely date of birth is a century later.[7]

Chronicles appears to be largely the work of a single individual, with some later additions and editing. The writer was probably male, probably a Levite (temple priest), and probably from Jerusalem. He was well read, a skilled editor, and a sophisticated theologian. His intention was to use Israel's past to convey religious messages to his peers, the literary and political elite of Jerusalem in the time of the Achaemenid Empire.[5]

Jewish and Christian tradition identified this author as the 5th century BC figure Ezra, who gives his name to the Book of Ezra; Ezra was also believed to be the author of both Chronicles and Ezra–Nehemiah, but later critical scholarship abandoned the identification with Ezra and called the anonymous author "the Chronicler". One of the most striking, although inconclusive, features of Chronicles is that its closing sentence is repeated as the opening of Ezra–Nehemiah.[5] The last half of the 20th century saw a radical reappraisal, and many now regard it as improbable that the author of Chronicles was also the author of the narrative portions of Ezra–Nehemiah.[8]

Sources

Much of the content of Chronicles is a repetition of material from other books of the Bible, from Genesis to Kings, and so the usual scholarly view is that these books, or an early version of them, provided the author with the bulk of his material. It is, however, possible that the situation was rather more complex, and that books such as Genesis and Samuel should be regarded as contemporary with Chronicles, drawing on much of the same material, rather than a source for it. There is also the question of whether the author of Chronicles used sources other than those found in the Bible: if such sources existed, it would bolster the Bible's case to be regarded as a reliable history. Despite much discussion of this issue, no agreement has been reached.[9]

Genre

The translators who created the Greek version of the Hebrew Bible (the Septuagint) called this book "Things Left Out", indicating that they thought of it as a supplement to another work, probably Genesis-Kings, but the idea seems inappropriate, since much of Genesis-Kings has been copied almost without change. Some modern scholars proposed that Chronicles is a midrash, or traditional Jewish commentary, on Genesis-Kings, but again this is not entirely accurate, since the author or authors do not comment on the older books so much as use them to create a new work. Recent suggestions have been that it was intended as a clarification of the history in Genesis-Kings, or a replacement or alternative for it.[10]

Themes

The message which the author wished to give to his audience was this:

- God is active in history, and especially the history of Israel. The faithfulness or sins of individual kings are immediately rewarded or punished by God. (This is in contrast to the theology of the Books of Kings, where the faithlessness of kings was punished on later generations through the Babylonian exile).[11]

- God calls Israel to a special relationship. The call begins with the genealogies (chapters 1–9 of 1 Chronicles), gradually narrowing the focus from all mankind to a single family, the Israelites, the descendants of Jacob. "True" Israel is those who continue to worship Yahweh at the Temple in Jerusalem, with the result that the history of the historical kingdom of Israel is almost completely ignored.[12]

- God chose David and his dynasty as the agents of his will. According to the author of Chronicles, the three great events of David's reign were his bringing the ark of the Covenant to Jerusalem, his founding of an eternal royal dynasty, and his preparations for the construction of the Temple.[12]

- God chose the Temple in Jerusalem as the place where he should be worshiped. More time and space are spent on the construction of the Temple and its rituals of worship than on any other subject. By stressing the central role of the Temple in pre-exilic Judah, the author also stresses the importance of the newly-rebuilt Persian-era Second Temple to his own readers.

- God remains active in Israel. The past is used to legitimise the author's present: this is seen most clearly in the detailed attention he gives to the Temple built by Solomon, but also in the genealogy and lineages, which connect his own generation to the distant past and thus make the claim that the present is a continuation of that past.[13]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Japhet 1993, p. 1-2.

- ↑ Japhet 1993, p. 1.

- ↑ Coggins 2003, p. 282.

- ↑ Japhet 1993, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 McKenzie 2004.

- ↑ New Spirit-Filled Life Bible, Thomas Nelson, 2002, p. 519

- ↑ Isaac Kalimi (January 2005). An Ancient Israelite Historian: Studies in the Chronicler, His Time, Place and Writing. Uitgeverij Van Gorcum. pp. 61–64. ISBN 978-90-232-4071-6.

- ↑ Beentjes 2008, p. 3.

- ↑ Coggins 2003, p. 283.

- ↑ Beentjes 2008, p. 4-6.

- ↑ Hooker 2001, p. 6.

- 1 2 Hooker 2001, p. 7-8.

- ↑ Hooker 2001, p. 6-10.

Bibliography

- Beentjes, Pancratius C. (2008). Tradition and Transformation in the Book of Chronicles. Brill. ISBN 9789004170445.

- Coggins, Richard J. (2003). "1 and 2 Chronicles". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Hooker, Paul K. (2001). First and Second Chronicles. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664255916.

- Japhet, Sara (1993). I and II Chronicles: A Commentary. SCM Press. ISBN 9780664226411.

- Kalimi, Isaac (2005). The Reshaping of Ancient Israelite History in Chronicles. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060583.

- Kelly, Brian E. (1996). Retribution and Eschatology in Chronicles. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9780567637796.

- Klein, Ralph W. (2006). 1 Chronicles: A Commentary. Fortress Press.

- Knoppers, Gary N. (2004). 1 Chronicles: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. Doubleday.

- McKenzie, Steven L. (2004). 1–2 Chronicles. Abingdon. ISBN 9781426759802.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Books of Chronicles. |

Translations

- Divrei Hayamim I – Chronicles I (Judaica Press) translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- Divrei Hayamim II – Chronicles II (Judaica Press) translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- 1 Chronicles at Biblegateway

- 2 Chronicles at Biblegateway

- 1 Chronicles at Bible-Book.org

- 2 Chronicles at Bible-Book.org

Introductions

![]()

Books of Chronicles | ||

| Preceded by Ezra-Nehemiah |

Hebrew Bible | Succeeded by None |

| Preceded by 1–2 Kings |

Western Old Testament | Succeeded by Ezra |

| Eastern Old Testament | Succeeded by 1 Esdras | |