Authorship of the Bible

| Part of a series on the |

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Perspectives |

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

Table I gives an overview of the periods and dates ascribed to the various books of the Bible. Tables II, III and IV outline the conclusions of the majority of contemporary scholars on the composition of the Hebrew Bible (the Protestant Old Testament), the deuterocanonical works (also called the apocrypha), and the New Testament.

Table I: Chronological overview (Hebrew Bible/Old Testament)

This table summarises the chronology of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament; the Deuteroncanonical works date from the 3rd century BCE to the 3rd century CE (see Table III), and the New Testament writings from the 1st and 2nd centuries CE (see Table IV). Dates are approximate, and mark the completion of the works rather than earlier source materials.

| Period | Books |

|---|---|

| Monarchic 8th–6th centuries BCE c. 745–586 BCE |

|

| Exilic 6th century BCE 586–539 BCE |

|

| Post-exilic Persian 6th–4th centuries BCE 538–330 BCE |

|

| Post-exilic Hellenistic 4th–2nd centuries BCE 330–164 BCE |

|

| Maccabean/Hasmonean/Roman 2nd century BCE-1st century CE 164–4 BCE |

|

Table II: Hebrew Bible/Protestant Old Testament

The Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, is the collection of scriptures making up the Bible used by Judaism; the same books, in a slightly different order, also make up the Protestant version of the Old Testament. The order used here follows the divisions used in Jewish Bibles.

| Torah | |

|---|---|

| Genesis Exodus Leviticus Numbers Deuteronomy |

Scholars are broadly agreed in placing the Torah in the mid-Persian period (the 5th century BCE).[28] Deuteronomy, the oldest of the five books, originated in the second half of the 7th century BCE as the law-code contained in Deuteronomy 5-26; chapters 1-4 and 29-30 were added around the end of the Babylonian exile when it became the introduction to the Deuteronomistic history (Joshua-2 Kings), and the remaining chapters were added in the late Persian period when it was revised to conclude Genesis-Exodus-Leviticus-Numbers.[29] The tradition behind the books stretches back some two hundred years to a point in the late 7th century BCE,[30] but questions surrounding the number and nature of the sources involved, and the processes and dates, remain unsettled.[31] Many theories have been advanced to explain the social and political background behind the composition of the Torah, but two have been especially influential.[32] The first of these, Persian Imperial authorisation, advanced by Peter Frei in 1985, holds that the Persian authorities required the Jews of Jerusalem to present a single body of law as the price of local autonomy.[33] Frei's theory was demolished at a symposium held in 2000, but the relationship between the Persian authorities and Jerusalem remains a crucial question.[34] The second theory, associated with Joel P. Weinberg and called the "Citizen-Temple Community", proposes that the Exodus story was composed to serve the needs of the post-exilic Jewish community, serving as an "identity card" defining who belonged to "Israel."[35] |

| Prophets | |

| Former Prophets: | The proposal that Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings make up a unified work (the Deuteronomistic history) was advanced by Martin Noth in 1943 and has been widely accepted, with revisions.[8] Noth proposed that the entire history was the creation of a single individual, who was working in the exilic period (6th century BCE). Since then, there has been wide recognition that the history appeared in at least two "editions", the first in the reign of Judah's King Josiah (late 7th century BCE), the second during the Babylonian exile (6th century BCE).[8] Few scholars accept his idea that the History was the work of a single individual.[36] |

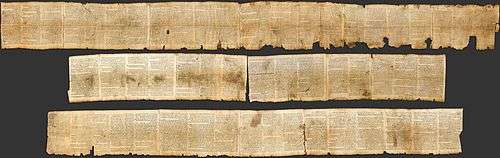

| Three Major Prophets: |  The Isaiah scroll, the oldest surviving manuscript of Isaiah, found among the Dead Sea Scrolls and dating from about 150 to 100 BCE.[37] Isaiah includes the work of three or more prophets.[38] The nucleus of Proto-Isaiah (chapters 1-39) contains the words of the original Isaiah; Deutero-Isaiah (chapters 40-55) is from an anonymous Exilic author; and Trito-Isaiah (chapters 56-66) is a post-exilic anthology.[39][40] Other anonymous authors and editors have inserted various passages into these three: chapters 36-39, for example, have been copied from 2 Kings 18-20, and the Suffering Servant poems, now scattered through Isaiah 42, 49, 50 and 52, were probably an independent composition.[41][42] Jeremiah exists in two versions, Greek (the version used in Orthodox Bibles) and Hebrew (Jewish, Catholic and Protestant Bibles), with the Greek probably finalised in the early Persian period and the Hebrew dating from some point between then and the 2nd century BCE.[12] The two differ significantly, with the Greek version generally regarded as being more authentic.[43] Scholars find it difficult to identify the words of the historic prophet Jeremiah, although the text presumably preserves his orally-delivered sayings, but the text itself is the end-product of a long process involving, among others, Exilic Deuteronomists, post-exilic restorationists, and later editors and authors responsible for the modern Greek and Hebrew texts.[44] Ezekiel presents itself as the words of the Ezekiel ben-Buzi, a priest of Jerusalem living in exile in Babylon.[45] While the book probably reflects much of the historic Ezekiel, it is the product of a long and complex history.[46] There is general agreement that the final product is the product of a highly educated priestly circle, which owed allegiance to the historical Ezekiel and was closely associated with the Second Temple.[47] Like Jeremiah, it exists in a longer Hebrew edition (Jewish, Catholic and Protestant Bibles) and a shorter Greek version, with the Greek probably representing an earlier stage of transmission.[48] |

| Twelve Minor Prophets | The Twelve Minor Prophets is a single book Jewish bibles, and this seems to have been the case since the first few centuries before the current era.[49] With the exception of Jonah, which is a fictional work, it is generally assumed that there exists an original core of tradition behind each book that can be attributed to the prophet for whom it is named, but the dates for several of the books (Joel, Obadiah, Jonah, Nahum, Zechariah 9-14 and Malachi) are debated.[50][51][52]

|

| Writings | |

| Poetic books: Psalms Job Proverbs |

|

| Five Scrolls Canticles Ruth Lamentations Ecclesiastes Esther |

|

| Histories Daniel Chronicles Ezra-Nehemiah |

|

Table III: Deuterocanonical Old Testament

The Deuterocanonical works are books included in Catholic and Orthodox but not in Jewish and Protestant Bibles.

| Book | |

|---|---|

| Book of Tobit | Tobit can be dated to 225–175 BCE on the basis of its use of language and lack of knowledge of the 2nd century BCE persecution of Jews.[75] |

| 1 Esdras | 1 Esdras is based on Chronicles and Ezra-Nehemiah.[76] |

| 2 Esdras | 2 Esdras is a composite work combining texts from the 1st, 2nd and 3rd centuries CE.[77] |

| Book of Judith | Judith is of uncertain origin, but probably dates from the second half of the 2nd century BCE.[78] |

| 1 Maccabees | 1 Maccabees is the work of an educated Jewish historian writing around 100 BCE.[79] |

| 2 Maccabees | 2 Maccabees is a revised and condensed version of a work by an otherwise unknown author called Jason of Cyrene, plus passages by the anonymous editor who made the condensation (called "the Epitomist"). Jason most probably wrote in the mid to late 2nd century BCE, and the Epitomist before 63 BCE.[80] |

| 3 Maccabees | 3 Maccabees was probably written by a Jew of Alexandria c. 100–75 BCE.[81] |

| 4 Maccabees | 4 Maccabees was probably composed in the middle half of the 1st century CE by a Jew living in Roman Syria or Asia Minor.[82] |

| Wisdom of Sirach | Sirach (known under several titles) names its author as Jesus ben Sirach, probably a scribe offering instruction to the youth of Jerusalem.[83] His grandson's preface to the Greek translation indirectly dates the work to the first quarter of the 2nd century BCE.[83] |

| Wisdom of Solomon | The Wisdom of Solomon probably dates from 100 to 50 BCE, and originated with the Pharisees of the Egyptian Jewish community.[84] |

| Additions to Esther | The Additions to Esther in the Greek translation date from the late 2nd or early 1st century BCE.[85] |

| Additions to Daniel | The three Additions to Daniel - the Prayer of Azariah and Song of the Three Holy Children, Susanna, and Bel and the Dragon - probably date from the 2nd century BCE, although Bel is difficult to place.[86] |

| Prayer of Manasseh | The Prayer of Manasseh probably dates from the 2nd or 1st centuries BCE.[87] |

| Baruch | Baruch was probably written in the 2nd century BCE - part of it, the Letter of Jeremiah, is sometimes treated as a separate work.[88] |

| Letter of Jeremiah | The Letter of Jeremiah, part of Baruch, is sometimes treated as a separate work.[88] |

| Additional psalms | The additional psalms are numbered 151–155; some at least are pre-Christian in origin, being found among the Dead Sea Scrolls.[89] |

Table IV: New Testament

| Gospels and Acts | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pauline epistles (undisputed) |

Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians, Philemon[109] |

| Epistle to the Romans | c. 57 CE. Written to the Romans as Paul the Apostle was about to leave Asia Minor and Greece. He was expressing his hopes to continue his work in Hispania.[90] |

| Corinthians | c. 56 CE. Another of the genuine Pauline letters. Paul expresses his intention to re-visit the church which he had founded in the city of Corinth c. 50–52 CE.[90] |

| Galatians | c. 55 CE. Paul does not express any wish to revisit the church in Galatia, which he had founded, and so some scholars believe the letter dates from the end of his missionary work. The letter concerns the question of whether Gentile converts to Christianity are required to adopt full Jewish customs.[90] |

| Epistle to the Philippians | c. 54–55 CE. A genuine Pauline letter, it mentions "Caesar's household," leading some scholars to believe that it is written from Rome, but some of the news in it could not have come from Rome. It rather seems to date from an earlier imprisonment of Paul, perhaps in Ephesus. In the epistle, Paul hopes to be released from prison.[90] |

| First Epistle to the Thessalonians | c. 51 CE. One of the earliest of the genuine Pauline epistles.[90] |

| Philemon | c. 54–55 CE. A genuine Pauline epistle, written from an imprisonment (probably in Ephesus) that Paul expects will soon be over.[90] |

| Deutero-Pauline epistles | |

| Ephesians | c. 80–90 CE. The letter appears to have been written after Paul's death, by an author who uses his name.[90] |

| Colossians | c. 62–70 CE. Some scholars believe Colossians dates from Paul's imprisonment in Ephesus around 55 CE, but differences in the theology suggest that it comes from much later in his career, around the time of his imprisonment in Rome.[90] |

| Second Epistle to the Thessalonians | c. 51 CE or post-70 CE. If this is a genuine Pauline epistle it follows closely on 1 Thessalonians. But some of the language and theology point to a much later date, from an unknown author using Paul's name.[90] |

| Pastoral epistles | |

| c. 100 CE. The three Pastoral epistles – First and Second Timothy and Titus, are probably from the same author,[110] but reflect a much more developed Church organisation than that reflected in the genuine Pauline epistles.[90] Most scholars regard them as the work of someone other than Paul.[111][112] | |

| Epistle to the Hebrews | |

| c. 80–90 CE. The elegance of the Greek language-text and the sophistication of the theology do not fit the genuine Pauline epistles, but the mention of Timothy in the conclusion led to its being included with the Pauline group from an early date.[90] Pauline authorship is now generally rejected, and the real author is unknown.[113] | |

| General epistles | |

| James | c. 65–85 CE. The traditional author is James the Just, "a servant of God and brother of the Lord Jesus Christ". Like Hebrews, James is not so much a letter as an exhortation; the style of the Greek language-text makes it unlikely that it was actually written by James, the brother of Jesus. Most scholars regard all the letters in this group as pseudonymous.[90] |

| First Epistle of Peter | c. 75–90 CE[90] |

| Second Epistle of Peter | c. 110 CE. The epistle's quotes from Jude, assumes a knowledge of the Pauline letters, and includes a reference to the gospel story of the Transfiguration of Christ, all signs of a comparatively late date.[90] |

| Johannine epistles | 90–110 CE.[114] The letters give no clear indication of their date, but scholars tend to place them about a decade after the Gospel of John.[114] |

| Jude | Uncertain date. The references to the "brother of James" and to "what the apostles of our Lord Jesus Christ foretold" suggest that it was written after the apostolic letters were in circulation, but before 2 Peter, which quotes it.[90] |

| Apocalypse | |

| Revelation | c. 95 CE. The date is suggested by clues in the visions, which point to the reign of the emperor Domitian (reigned 81-96 CE).[90] Domitian was assassinated on 18 September 96, in a conspiracy by court officials.[115] The author was traditionally believed to be the same person as both John the Apostle/John the Evangelist, the traditional author of the Fourth Gospel – the tradition can be traced to Justin Martyr, writing in the early 2nd century.[116] Most biblical scholars now believe that these were separate individuals.[117][118] The name "John" suggests that the author was a Christian of Jewish descent, and although he never explicitly identifies himself as a prophet it is likely that he belonged to a group of Christian prophets and was known as such to members of the churches in Asia Minor. Since the 2nd century the author has been identified with one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus. This is commonly linked with an assumption that the same author wrote the Gospel of John. Others, however, have argued that the author could have been John the Elder of Ephesus, a view which depends on whether a tradition cited by Eusebius was referring to someone other than the apostle. The precise identity of "John" therefore remains unknown.[119] The author is disambiguated from others as John of Patmos, because the author identified himself as an exile to the island of Patmos. |

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 Kelle 2005, p. 9.

- ↑ Brettler 2010, p. 161–162.

- ↑ Radine 2010, p. 71-72.

- 1 2 Rogerson 2003a, p. 690.

- ↑ O'Brien 2002, p. 14.

- ↑ Gelston 2003c, p. 715.

- 1 2 3 Rogerson 2003b, p. 154.

- 1 2 3 Campbell & O'Brien 2000, p. 2 and fn.6.

- ↑ Gelston 2003a, p. 710.

- ↑ Brettler 2007, p. 311.

- ↑ Gelston 2003b, p. 696.

- 1 2 3 Sweeney 2010, p. 94.

- ↑ Sweeney 2010, p. 135-136.

- 1 2 Blenkinsopp 2007, p. 974.

- ↑ Carr 2011, p. 342.

- ↑ Greifenhagen 2003, p. 212.

- ↑ Enns 2012, p. 5.

- 1 2 Nelson 2014, p. 214.

- 1 2 Nelson 2014, p. 214-215.

- 1 2 Carroll 2003, p. 730.

- ↑ McKenzie 2004, p. 32.

- ↑ Grabbe 2003, p. 00.

- ↑ Meyers 2007, p. 325.

- 1 2 3 Rogerson 2003c, p. 8.

- 1 2 Nelson 2014, p. 217.

- 1 2 Day 1990, p. 16.

- 1 2 Collins 2002, p. 2.

- ↑ Romer 2008, p. 2 and fn.3.

- ↑ Rogerson 2003b, p. 153-154.

- ↑ McEntire 2008, p. 8.

- ↑ Bandstra 2008, p. 19-21.

- ↑ Ska 2006, pp. 217.

- ↑ Ska 2006, pp. 218.

- ↑ Eskenazi 2009, p. 86.

- ↑ Ska 2006, p. 225-227.

- ↑ Person 2010, p. 10-11.

- ↑ Goldingay 2001, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Brettler 2008, p. 161.

- ↑ Soggin 1989, p. 394.

- ↑ Sweeney 1998, p. 78.

- ↑ Brettler 2010, p. 161-162.

- ↑ Lemche 2008, p. 20.

- ↑ Davidson 1993, p. 344-345.

- ↑ Diamond 2003, p. 546.

- ↑ Goldingay 2003, p. 623.

- ↑ Joyce 2009, p. 16.

- ↑ Blenkinsopp 1996, p. 167-168.

- ↑ Blenkinsopp 1996, p. 166.

- ↑ Redditt 2003, pp. 1.

- ↑ Floyd 2000, p. 9.

- ↑ Dell 1996, pp. 86–89.

- ↑ Redditt 2003, pp. 2.

- ↑ Emmerson 2003, p. 676.

- ↑ Nelson 2014, p. 216.

- ↑ Carroll 2003, p. 690.

- ↑ Gelston 2003, p. 696.

- ↑ Rogerson 2003, p. 708.

- ↑ Gelston 2003, p. 710.

- ↑ Gelston 2003, p. 715.

- ↑ Coogan, Brettler & Newsom 2007, p. xxiii.

- ↑ Crenshaw 2007, p. 332.

- ↑ Crenshaw 2007, p. 331.

- ↑ Whybray 2005, p. 181.

- ↑ Crenshaw 2010, p. 66.

- ↑ Snell 1993, p. 8.

- ↑ Exum 2005, p. 33-37.

- ↑ Bush 2018, p. unpaginated.

- ↑ Crenshaw 2010, p. 144-145.

- ↑ Hayes 1998, p. 168.

- ↑ Dobbs-Allsopp 2002, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Crawford 2003, p. 329.

- ↑ Collins 1999, p. 219.

- ↑ Graham 1998, p. 210.

- ↑ Grabbe 2003, p. 313-314.

- ↑ FitzMyer 2003, p. 51.

- ↑ Japhet 2007, p. 751.

- ↑ Schmitt 2003b, p. 876.

- ↑ West 2003, p. 748.

- ↑ Bartlett 2003, p. 807-808.

- ↑ Bartlett 2003, p. 831-832.

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 866.

- ↑ deSilva 2003, p. 888.

- 1 2 Collins 2007, p. 667.

- ↑ Horbury 2007, p. 650-653.

- ↑ Meyer 2007, p. 325.

- ↑ Rogerson 2003, p. 803-806.

- ↑ Towner 1990, p. 544.

- 1 2 Schmitt 2003a, p. 799.

- ↑ Thornhill 2015, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Perkins 2012, p. 19ff.

- ↑ Theissen, Gerd and Annette Merz. The historical Jesus: a comprehensive guide. Fortress Press. 1998. translated from German (1996 edition). pp. 24–27.

- ↑ Jens Schroter, Gospel of Mark, in Aune, p. 278

- ↑ Perkins 1998, p. 241.

- ↑ Duling 2010, p. 298-299.

- ↑ "Matthew, Gospel acc. to St." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ↑ Dennis C. Duling, Gospel of Matthew, in Aune, David E., (ed) "The Blackwell companion to the New Testament" (Blackwell Publishing, 2010), pp. 302–03.

- ↑ Dennis C. Duling, Gospel of Matthew, in Aune, David E., (ed) "The Blackwell companion to the New Testament" (Blackwell Publishing, 2010), p. 296

- ↑ France 2007, p. 18.

- ↑ Charlesworth 2008, p. unpaginated.

- ↑ Horrell, DG, An Introduction to the study of Paul, T&T Clark, 2006, 2nd Ed., p. 7; cf. W. L. Knox, The Acts of the Apostles (1948), pp. 2–15 for detailed arguments that still stand.

- ↑ David E. Aune, "The New Testament in its literary environment" (Westminster John Knox Press, 1987) p. 77

- ↑ Robbins, Vernon. "By Land and By Sea: The We-Passages and Ancient Sea Voyages." In C. H. Talbert, ed. Perspectives on Luke-Acts. Perspectives in Religious Studies, Special Studies Series, No. 5. Macon, Ga: Mercer Univ. Press and Edinburgh: T.& T. Clark, 1978: 215–42.

- ↑ Boring 2012, p. 587.

- ↑ Perkins 2009, p. 250–253.

- 1 2 Lincoln 2005, p. 18.

- ↑ The Gospel and Epistles of John: a concise commentary Raymond Edward Brown (Liturgical Press, 1988) p. 10

- ↑ Barnabas Lindars, "John" (Sheffield Academic Press, 1990) p.11

- ↑ David E. Aune "The New Testament in its literary environment" (Westminster John Knox Press, 1987) p. 20

- ↑ Perkins 2003, p. 1274.

- ↑ Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible (ed. James D. G. Dunn, John William Rogerson, Eerdmans, 2003) p. 1274

- ↑ Ehrman 2004:385

- ↑ Ehrman, Bart D. (February 2011). "3. Forgeries in the Name of Paul. The Pastoral Letters: 1 and 2 Timothy and Titus" (EPUB). Forged: Writing in the Name of God – Why the Bible's Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are (First Edition. EPub ed.). New York: HarperCollins e-books. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-06-207863-6.

Before showing why most scholars consider them to be written by someone other than Paul, I should give a brief summary of each letter.

- ↑ Fonck, Leopold. "Epistle to the Hebrews." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. Web: 30 Dec. 2009.

- 1 2 Kim 2003, p. 250.

- ↑ Jones (1992), p. 193

- ↑ Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, 81.4

- ↑ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. p. 355

- ↑ Ehrman, Bart D. (2004). The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. New York: Oxford. p. 468. ISBN 978-0-19-515462-7.

- ↑ "Eerdmans commentary on the Bible", James D. G. Dunn, John William Rogerson (eds) p. 1535

Bibliography 1

- Alexander, Philip S. (2003). "3 Maccabees". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Allen, Leslie C. (2008). Jeremiah: A Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664222239.

- Alter, Dennis (2009). The Book of Psalms: A Translation with Commentary. W. W. Norton. ISBN 9780393337044.

- Bartlett, John R. (2003). "1 Maccabees". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Bernstein, Alan E. (1996). The Formation of Hell: Death and Retribution in the Ancient and Early Christian Worlds. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801481314.

- Berquist, Jon L. (2007). Approaching Yehud: New Approaches to the Study of the Persian Period. SBL Press. ISBN 9781589831452.

- Biddle, Mark E. (2007). "Jeremiah". In Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195288803.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2007). "Isaiah". In Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195288803.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (1996). A history of prophecy in Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664256395.

- Boring, M. Eugene (2012). An Introduction to the New Testament: History, Literature, Theology. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664255923.

- Brettler, Mark Zvi (2007). "Introduction to the Historical Books". In Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195288803.

- Brettler, Marc Zvi (2010). How to read the Bible. Jewish Publication Society. ISBN 978-0-8276-0775-0.

- Brueggemann, Walter (2003). An introduction to the Old Testament: the canon and Christian imagination. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 978-0-664-22412-7.

- Bush, Frederic W. (2018). Ruth-Esther. Zondervan. ISBN 9780310588283.

- Campbell, Antony F.; O'Brien, Mark A. (2000). Unfolding the Deuteronomistic History. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451413687.

- Carr, David (2011). The Formation of the Hebrew Bible: A New Reconstruction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199742608.

- Carr, David (2000). "Genesis, Book of". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Carroll, M. Daniel (2003). "Amos". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Carroll, M. Daniel (2003). "Malachi". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Charlesworth, James H. (2008). The Historical Jesus: An Essential Guide. Abingdon Press. ISBN 9781426724756.

- Collins, John J. (2007). "Ecclesiasticus, or the Wisdom of Jesus son of Sirach". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John. Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199277186.

- Collins, John J. (2002). "Current Issues in the Study of Daniel". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron. The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004116757.

- Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann (2007). "Editors' Introduction". In Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195288803.

- Crawford, Sidnie White (2003). "Esther". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Crenshaw, James L. (2007). "Job". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John. Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199277186.

- Crenshaw, James L. (2010). Old Testament Wisdom: An Introduction. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664234591.

- Davidson, Robert (1993). "Jeremiah, Book of". In Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael D. The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199743919.

- Day, John (1990). The Psalms. Old Testament guides. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-85075-703-0.

- Dell, Katherine J. (2003). "Job". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Dell, Katherine J (1996). "Reinventing the Wheel: the Shaping of the Book of Jonah". In Barton, John; Reimer, David James. After the exile: essays in honour of Rex Mason. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-8655-45243.

- deSilva, David A. (2003). "4 Maccabees". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Diamond, A. R. Pete (2003). "Jeremiah". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Dobbs-Allsopp, F.W. (2002). Lamentations. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664237547.

- Dozeman, Thomas (2000). "Exodus, Book of". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Duling, Dennis C. (2010). "The Gospel of Matthew". In Aune, David E. The Blackwell Companion to the New Testament. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-0825-6.

- Emmerson, Grace I. (2003). "Hosea". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Enns, Peter (2012). The Evolution of Adam. Baker Books. ISBN 9781587433153.

- Evans, Craig A. (2008-10-01). "Introduction". In Evans, Craig A.; Tov, Emanuel. Exploring the Origins of the Bible: Canon Formation in Historical, Literary, and Theological Perspective. Acadia Studies in Bible and Theology. Baker Academic (published 2008). ISBN 9781585588145.

- Exum, J. Cheryl (2005). Song of songs: a commentary. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Fitzmyer, Joseph A. (2003). Tobit. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110175745.

- Floyd, Michael H (2000). Minor prophets. 2. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802844521.

- France, R.T (2007). The Gospel of Matthew. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802825018.

- Gelston, Anthony (2003a). "Habakkuk". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Gelston, Anthony (2003b). "Obadiah". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Gelston, Anthony (2003c). "Zephaniah". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Goldingay, John A. (2003). "Ezekiel". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2003). "Ezra". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Graham, M. Patrick (1998). "The "Chronicler's History": Ezra-Nehemiah, 1–2 Chronicles". In Graham, M.P; McKenzie, Steven L. The Hebrew Bible Today: An Introduction to Critical Issues. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664256524.

- Greifenhagen, Franz V. (2003). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780567391360.

- Habel, Norman (1985). The Book of Job: A Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664222185.

- Haymen, A. Peter (2003). "Wisdom of Solomon". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Horbury, William (2007). "The Wisdom of Solomon". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John. Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199277186.

- Houston, Walter J (2003). "Leviticus". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Bible Commentary. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Japhet, Sarah (2007). "1 Esdras". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John. Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199277186.

- Jones, Brian W. (1992). The Emperor Domitian. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-10195-0.

- Joyce, Paul M. (2009). Ezekiel: A Commentary. Continuum. ISBN 9780567483614.

- Kelle, Brad E. (2005). Hosea 2: Metaphor and Rhetoric in Historical Perspective. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 9781589831896.

- Kselman, John S. (2007). "Psalms". In Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195288803.

- Kim, P.J (2003). "Letters of John". In Aune, David. Westminster Dictionary of the New Testament and Early Christian Literature. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664219178.

- Lemche, Niels Peter (2008). The Old Testament between theology and history: a critical survey. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664232450.

- Lincoln, Andrew (2005). Gospel According to St John. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781441188229.

- Mathys, H.P. (2001). "1 and 2 Chonicles". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John. Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198755005.

- McDermott, John J (2002). Reading the Pentateuch: a historical introduction. Pauline Press. ISBN 9780809140824.

- Miller, Patrick D. (1990). Deuteronomy. John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664237370.

- McEntire, Mark (2008). Struggling with God: An Introduction to the Pentateuch. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780881461015.

- McKenzie, Steven L. (2004). Abingdon Old Testament Commentaries: I & II Chronicles. Abingdon Press. ISBN 9781426759802.

- Meyers, Carol (2007). "Esther". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John. Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1992-77186.

- Nelson, Richard D. (2014). Historical Roots of the Old Testament (1200–63 BCE). SBL Press. ISBN 9781628370065.

- O'Brien, Julia M. (2002). Nahum. A&C Black. ISBN 9781841273006.

- Perkins, Pheme (2012). Reading the New Testament: An Introduction. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809147861.

- Perkins, Pheme (1998). "The Synoptic Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles: Telling the Christian Story". In Barton, John. The Cambridge companion to biblical interpretation. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 241–58. ISBN 978-0-521-48593-7.

- Person, Raymond F. (2010). The Deuteronomic History and the Book of Chronicles. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 9781589835177.

- Queen-Sutherland, Kandy M. (2002). "Additions to Esther". In Mills, Watson E.; Wilson, Richard F. The Deuterocanonicals/Apocrypha. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865545106.

- Radine, Jason (2010). The Book of Amos in Emergent Judah. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161501142.

- Redditt, Paul L (2003). "The Formation of the Book of the Twelve". In Redditt, Paul L; Schart, Aaron. Thematic threads in the Book of the Twelve. ISBN 9783110175943.

- Rogerson, John W. (2003a). "Micah". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Rogerson, John W. (2003b). "Deuteronomy". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Rogerson, John W. (2003c). "The History of the Tradition: Old Testament and Apocrypha". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Rogerson, John W. (2003d). "Nahum". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Rogerson, John W. (2003e). "Additions to Daniel". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Romer, Thomas (2008). "Moses Outside the Torah and the Construction of a Diaspora Identity" (PDF). The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures. 8, article 15: 2–12.

- Satlow, Michael L. (2014). How the Bible Became Holy. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300171914.

- Schmitt, John J. (2003a). "Baruch". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Schmitt, John J. (2003b). "2 Esdras". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Schniedewind, William M. (2005). How the Bible Became a Book. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521536226.

- Ska, Jean-Louis (2006). Introduction to reading the Pentateuch. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061221.

- Snaith, John (2003). "Sirach". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Snell, Daniel C. (1993). Twice-told Proverbs and the composition of the book of Proverbs. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9780931464669.

- Spencer, Richard A. (2002). "Additions to Daniel". In Mills, Watson E.; Wilson, Richard F. Mercer Commentary on the Bible: The Deuterocanonicals/Apocrypha. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865545106.

- Stromberg, Jake (2011). An Introduction to the Study of Isaiah. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 9780567363305.

- Sweeney, Marvin A. (2010). The Prophetic Literature. Abingdon Press. ISBN 9781426730030.

- Sweeney, Marvin A. (1998). "The Latter Prophets". In McKenzie, Steven L.; Graham, Matt Patrick. The Hebrew Bible Today: An Introduction to Critical Issues. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664256524.

- Thornhill, A. Chadwick (2015). The Chosen People: Election, Paul and Second Temple Judaism. InterVarsity Press.

- Towner, Sibley S. (1990). "Mannaseh, Prayer of". In Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey. Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press.

- Van Seters, John (2004). The Pentateuch: a social-science commentary. T&T Clark International. ISBN 9780567080882.

- Vogt, Peter T. (2009). Interpreting the Pentateuch: An Exegetical Handbook. Kregel Academic. ISBN 9780825427626.

- West, Gerald (2003). "Judith". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Whybray, Norman (2005). Wisdom: the collected articles of Norman Whybray. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754639176.

- Wright, J. Edward (1999). The Early History of Heaven. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198029816.

- Zvi, Ehud Ben (2004). "Introduction to The Twelve Minor Prophets". In Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Mark Zvi. The Jewish Study Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19529751-5.

Bibliography 2

- Olson, Roger E. (2016). The Mosaic of Christian Belief. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 9780830899708.

- Cohn-Sherbok, Dan (1996). The Hebrew Bible. A&C Black. ISBN 9780304337033.

- Jacobs, Louis (1995). The Jewish Religion: A Companion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198264637.

- Rabin, Elliott (2006). Understanding the Hebrew Bible: A Reader's Guide. KTAV Publishing House. ISBN 9780881258714.

- Römer, Thomas; De Pury, Albert (2000). "Deuteronomistic Historiography". In De Pury, Albert; Römer, Thomas; Macchi, Jean-Daniel. Israel Constructs Its History: Deuteronomistic Historiography in Recent Research. A&C Black. ISBN 9781841270999.

- Romer, Thomas, "The Future of the Deuteronomistic History" (Leuven University Press, 2000)

- Perdue, Leo G., ed. (2001). The Blackwell Companion to the Hebrew Bible. Blackwell. ISBN 9780631210719.

- Barton, John; Muddiman, John, eds. (2001). Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198755005.

- Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William, eds. (2003). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (February 2011). Forged: Writing in the Name of God—Why the Bible's Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are. HarperCollins. ISBN 9780062078636.

- Heschel, Abraham Joshua (2005). Heavenly Torah: As Refracted Through the Generations. A&C Black. ISBN 9780826408020.

- Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. 1991. ISBN 9780865543737.

- William David Davies, Steven T. Katz, Louis Finkelstein, "The Cambridge History of Judaism: The late Roman-Rabbinic period" (Cambridge University Press, 2006)

- Brueggemann, Walter, "Reverberations of Faith: A Theological Handbook of Old Testament Themes" (Westminster John Knox, 2002)

- Graham, M.P, and McKenzie, Steven L., "The Hebrew Bible Today: An Introduction to Critical Issues" (Westminster John Knox Press, 1998)

- Mays, James Luther, Petersen, David L., Richards, Kent Harold, "Old Testament Interpretation" (T&T Clark, 1995)

- Van Seters, John (1997). In Search of History: Historiography in the Ancient World and the Origins of Biblical History. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-013-2.

- Van Seters, John (2004). The Pentateuch: A Social-Science Commentary. T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-08088-2.

- Wiseman, D.J. (1970). "Books in the Ancient Near East and in the Old Testament". In Ackroyd, P.R.; Evans, C.F. The Cambridge History of the Bible: From the Beginnings to Jerome. I. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521099738.

- Collins, John J. (1999). "Daniel". In Van Der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; van der Horst, Pieter Willem. Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802824912.

Pentateuch

Deuteronomistic history

- de Moor, Johannes Cornelis, and Van Rooy, H. F. (eds), "Past, Present, Future: The Deuteronomistic History and the Prophets" (Brill, 2000)

- Albertz, Rainer (ed) "Israel in Exile: The History and Literature of the Sixth Century B.C.E." (Society of Biblical Literature, 2003)

- Romer, Thomas, "The Future of the Deuteronomistic History" (Leuven University Press, 2000)

- Marttila, Marko, "Collective Reinterpretation in the Psalms" (Mohr Siebeck, 2006)

Prophets and writings

- Miller, Patrick D. and Peter W. Flint, (eds) "The Book of Psalms: Composition and Reception" (Brill, 2005)

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph, "A History of Prophecy in Israel" (Westminster John Knox, 1996)

- Clemets, R.E., "Jeremiah" (John Knox Press, 1988)

- Allen, Leslie C., "Jeremiah: A Commentary" (Westminster John Knox Press, 2008)

- Sweeney, Marvin, "The Twelve Prophets" vol.1 (Liturgical Press, 2000)

- Sweeney, Marvin, "The Twelve Prophets" vol.2 (Liturgical Press, 2000)

New Testament

- Burkett, Delbert Royce, "An Introduction to the New Testament and the Origins of Christianity" (Cambridge University Press, 2002)

- Aune, David E., (ed) "The Blackwell Companion to the New Testament" (Blackwell Publishing, 2010)

- Mitchell, Margaret Mary, and Young, Frances Margaret, "Cambridge History of Christianity: Origins to Constantine" (Cambridge University Press, 2006)