Blade Runner

| Blade Runner | |

|---|---|

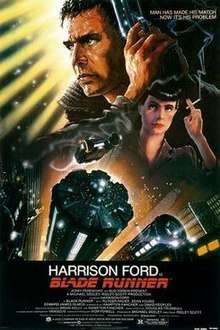

Theatrical release poster by John Alvin | |

| Directed by | Ridley Scott |

| Produced by | Michael Deeley |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on |

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Vangelis |

| Cinematography | Jordan Cronenweth |

| Edited by |

|

Production company |

|

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 117 minutes[1] |

| Country |

United States[2][3] Hong Kong[4] |

| Budget | $28 million[5] |

| Box office | $33.8 million[6] |

Blade Runner is a 1982 neo-noir science fiction film directed by Ridley Scott, written by Hampton Fancher and David Peoples, and starring Harrison Ford, Rutger Hauer, Sean Young, and Edward James Olmos. It is a loose adaptation of Philip K. Dick's novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968). The film is set in a dystopian future Los Angeles of 2019, in which synthetic humans known as replicants are bio-engineered by the powerful Tyrell Corporation to work on off-world colonies. When a fugitive group of replicants led by Roy Batty (Hauer) escapes back to Earth, burnt-out cop Rick Deckard (Ford) reluctantly agrees to hunt them down while questioning his and the replicants' humanity through his relationship with an advanced model, Rachael (Young).

Blade Runner initially underperformed in North American theaters and polarized critics; some praised its thematic complexity and visuals, while others were displeased with its unconventional pacing and plot. It later became an acclaimed cult film regarded as one of the all-time best science fiction movies. Hailed for its production design depicting a "retrofitted" future, Blade Runner is a leading example of neo-noir cinema. The soundtrack, composed by Vangelis, was nominated in 1983 for a BAFTA and a Golden Globe as best original score.

The film has influenced many science fiction films, video games, anime, and television series. It brought the work of Philip K. Dick to the attention of Hollywood, and several later big-budget films were based on his work. In the year after its release, Blade Runner won the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation, and in 1993 it was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". A sequel, Blade Runner 2049, was released in October 2017.

Seven versions of Blade Runner exist as a result of controversial changes made at the request of studio executives. A director's cut was released in 1992 after a strong response to test screenings of a workprint. This, in conjunction with the film's popularity as a video rental, made it one of the earliest movies to be released on DVD. In 2007, Warner Bros. released The Final Cut, a 25th-anniversary digitally remastered version, and the only version over which Scott retained artistic control.

Plot

In 2019 Los Angeles, former police officer Rick Deckard is detained by officer Gaff, and brought to his former supervisor, Bryant. Deckard, whose job as a "blade runner" was to track down bioengineered beings known as replicants and "retire" (kill) them, is informed that four are on Earth illegally. Deckard starts to leave, but Bryant ambiguously threatens him, and he stays. The two watch a video of a blade runner named Holden administering the "Voigt-Kampff" test, which is designed to distinguish replicants from humans based on their emotional response to questions. The test subject, Leon, shoots Holden on the second question. Bryant wants Deckard to retire Leon and the other three Tyrell Corporation Nexus-6 replicants: Roy Batty, Zhora, and Pris.

Bryant has Deckard meet with Eldon Tyrell so he can administer the test on a Nexus-6 to see if it works. Tyrell expresses his interest in seeing the test fail first and asks him to administer it on his assistant Rachael. After a much longer than standard test, Deckard concludes that Rachael is a replicant who believes she is human. Tyrell explains that she is an experiment who has been given false memories to provide an emotional "cushion".

Searching Leon's hotel room, Deckard finds photos and a synthetic snake scale. Roy and Leon investigate a replicant eye-manufacturing laboratory and learn of J. F. Sebastian, a gifted genetic designer who works closely with Tyrell. Deckard returns to his apartment where Rachael is waiting. She tries to prove her humanity by showing him a family photo, but after Deckard reveals that her memories are implants from Tyrell's niece, she leaves his apartment. Meanwhile, Pris locates Sebastian and manipulates him to gain his trust.

A photograph from Leon's apartment and the snake scale lead Deckard to a strip club, where Zhora works. After a confrontation and chase, Deckard kills Zhora. Bryant orders him also to retire Rachael, who has disappeared from the Tyrell Corporation. After Deckard spots Rachael in a crowd, he is attacked by Leon, who knocks Deckard's pistol out of his hand, and attempts to kill Deckard, but Rachael uses Deckard's pistol to kill Leon. They return to Deckard's apartment, and, during an intimate discussion, he promises not to track her down; as she abruptly tries to leave, Deckard restrains her, making her kiss him.

Arriving at Sebastian's apartment, Roy tells Pris that the others are dead. Sympathetic to their plight, Sebastian reveals that because of "Methuselah Syndrome", a genetic premature aging disorder, his life will also be cut short. Sebastian and Roy gain entrance into Tyrell's secure penthouse, where Roy demands more life from his maker. Tyrell tells him that it is impossible. Roy confesses that he has done "questionable things", but Tyrell dismisses this, praising Roy's advanced design and accomplishments in his short life. Roy kisses Tyrell, then kills him. Sebastian runs for the elevator, followed by Roy, who rides the elevator down alone.[nb 1] Deckard is later told by Bryant that Sebastian was found dead.

At Sebastian's apartment, Deckard is ambushed by Pris, but he kills her as Roy returns. Roy's body begins to fail as the end of his lifespan nears. He chases Deckard through the building, ending on the roof. Deckard tries to jump to an adjacent roof, but is left hanging between buildings. Roy makes the jump with ease, and as Deckard's grip loosens, Roy hoists him onto the roof, saving him. Before Roy dies, he delivers a monologue about how his memories "will be lost in time, like tears in rain". Gaff arrives and shouts to Deckard about Rachael: "It's too bad she won't live, but then again, who does?" Deckard returns to his apartment and finds Rachael asleep in his bed. As they leave, Deckard notices an origami unicorn on the floor, a calling card that recalls for him Gaff's earlier statement. Deckard and Rachael leave the apartment block.

Themes

The film operates on multiple dramatic and narrative levels. It employs some of the conventions of film noir, among them the character of a femme fatale; narration by the protagonist (in the original release); chiaroscuro cinematography; and giving the hero a questionable moral outlook – extended to include reflections upon the nature of his own humanity.[8][9] It is a literate science fiction film, thematically enfolding the philosophy of religion and moral implications of human mastery of genetic engineering in the context of classical Greek drama and hubris.[10] It also draws on Biblical images, such as Noah's flood,[11] and literary sources, such as Frankenstein.[12] Although fans claimed that the chess game between Sebastian and Tyrell was based on the famous Immortal Game of 1851, Scott said any similarity was merely coincidental.[13]

Blade Runner delves into the effects of technology on the environment and society by reaching to the past, using literature, religious symbolism, classical dramatic themes, and film noir techniques. This tension between past, present, and future is represented in the "retrofitted" future depicted in the film, one which is high-tech and gleaming in places but decayed and outdated elsewhere. In an interview with The Observer in 2002, director Ridley Scott described the film as "extremely dark, both literally and metaphorically, with an oddly masochistic feel". He also said that he "liked the idea of exploring pain" in the wake of his brother's death: "When he was ill, I used to go and visit him in London, and that was really traumatic for me."[14]

A sense of foreboding and paranoia pervades the world of the film: corporate power looms large; the police seem omnipresent; vehicle and warning lights probe into buildings; and the consequences of huge biomedical power over the individual are explored – especially regarding replicants' implanted memories. Control over the environment is exercised on a vast scale, and goes hand in hand with the absence of any natural life; for example, artificial animals stand in for their extinct predecessors. This oppressive backdrop explains the frequently referenced migration of humans to "off-world" (extraterrestrial) colonies.[15] The dystopian themes explored in Blade Runner are an early example of the expansion of cyberpunk concepts into cinema. Eyes are a recurring motif, as are manipulated images, calling into question the nature of reality and our ability to accurately perceive and remember it.[16][17]

These thematic elements provide an atmosphere of uncertainty for Blade Runner's central theme of examining humanity. In order to discover replicants, an empathy test is used, with a number of its questions focused on the treatment of animals – seemingly an essential indicator of one's "humanity". The replicants appear to show compassion and concern for one another and are juxtaposed against human characters who lack empathy, while the mass of humanity on the streets is cold and impersonal. The film goes so far as to question if Deckard might be an android, in the process asking the audience to re-evaluate what it means to be human.[18]

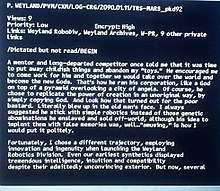

The question of whether Deckard is intended to be a human or a replicant has been an ongoing controversy since the film's release.[19] Both Michael Deeley and Harrison Ford wanted Deckard to be human, while Hampton Fancher preferred ambiguity.[20] Ridley Scott has stated that in his vision, Deckard is a replicant.[21][22]

Deckard's unicorn-dream sequence, inserted into the Director's Cut and concomitant with Gaff's parting gift of an origami unicorn, is seen by many as showing that Deckard is a replicant – because Gaff could have retrieved Deckard's implanted memories.[12][23] The interpretation that Deckard is a replicant is challenged by others who believe the unicorn imagery shows that the characters, whether human or replicant, share the same dreams and recognize their affinity,[24] or that the absence of a decisive answer is crucial to the film's main theme.[25] The film's inherent ambiguity and uncertainty, as well as its textual richness, have permitted multiple interpretations.[26]

Production

Cast

| Actor | Role |

|---|---|

| Harrison Ford | Rick Deckard |

| Rutger Hauer | Roy Batty |

| Sean Young | Rachael |

| Edward James Olmos | Gaff |

| M. Emmet Walsh | Bryant |

| Daryl Hannah | Pris |

| William Sanderson | J.F. Sebastian |

| Brion James | Leon Kowalski |

| Joe Turkel | Eldon Tyrell |

| Joanna Cassidy | Zhora Salome |

| James Hong | Chew |

| Morgan Paull | Dave Holden |

| Hy Pyke | Taffey Lewis |

Casting the film proved troublesome, particularly for the lead role of Deckard. Screenwriter Hampton Fancher envisioned Robert Mitchum as Deckard and wrote the character's dialogue with Mitchum in mind.[27] Director Ridley Scott and the film's producers spent months meeting and discussing the role with Dustin Hoffman, who eventually departed over differences in vision.[27] Harrison Ford was ultimately chosen for several reasons, including his performance in the Star Wars films, Ford's interest in the Blade Runner story, and discussions with Steven Spielberg who was finishing Raiders of the Lost Ark at the time and strongly praised Ford's work in the film.[27] Following his success in films like Star Wars (1977) and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), Ford was looking for a role with dramatic depth.[28] According to production documents, several actors were considered for the role, including Gene Hackman, Sean Connery, Jack Nicholson, Paul Newman, Clint Eastwood, Tommy Lee Jones, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Al Pacino, and Burt Reynolds.[27]

One role that was not difficult to cast was Rutger Hauer as Roy Batty, the violent yet thoughtful leader of the replicants.[29] Scott cast Hauer without having met him, based solely on Hauer's performances in Paul Verhoeven's movies Scott had seen (Katie Tippel, Soldier of Orange, and Turkish Delight).[27] Hauer's portrayal of Batty was regarded by Philip K. Dick as "the perfect Batty – cold, Aryan, flawless".[30] Of the many films Hauer has made, Blade Runner is his favorite. As he explained in a live chat in 2001, "Blade Runner needs no explanation. It just [is]. All of the best. There is nothing like it. To be part of a real masterpiece which changed the world's thinking. It's awesome."[31] Hauer rewrote his character's "tears in rain" speech himself and presented the words to Scott on set prior to filming.

Blade Runner used a number of then-lesser-known actors: Sean Young portrays Rachael, an experimental replicant implanted with the memories of Tyrell's niece, causing her to believe she is human;[32] Nina Axelrod auditioned for the role.[27] Daryl Hannah portrays Pris, a "basic pleasure model" replicant; Stacey Nelkin auditioned for the role, but was given another part in the film, which was ultimately cut before filming.[27] Casting Pris and Rachael was challenging, requiring several screen tests with Morgan Paull playing the role of Deckard. Paull was cast as Deckard's fellow bounty hunter Holden based on his performances in the tests.[27] Brion James portrays Leon Kowalski, a combat and laborer replicant, and Joanna Cassidy portrays Zhora, an assassin replicant.

Edward James Olmos portrays Gaff. Olmos drew on diverse ethnic sources to help create the fictional "Cityspeak" language his character uses in the film.[33] His initial address to Deckard at the noodle bar is partly in Hungarian and means, "Horse dick [bullshit]! No way. You are the Blade ... Blade Runner."[33] M. Emmet Walsh plays Captain Bryant, a hard-drinking, sleazy, and underhanded police veteran typical of the film noir genre. Joe Turkel portrays Dr. Eldon Tyrell, a corporate mogul who built an empire on genetically manipulated humanoid slaves. William Sanderson was cast as J. F. Sebastian, a quiet and lonely genius who provides a compassionate yet compliant portrait of humanity. J. F. sympathizes with the replicants, whom he sees as companions,[34] and he shares their shorter lifespan due to his rapid aging disease.[35] Joe Pantoliano had earlier been considered for the role.[36] James Hong portrays Hannibal Chew, an elderly geneticist specializing in synthetic eyes, and Hy Pyke portrayed the sleazy bar owner Taffey Lewis – in a single take, something almost unheard-of with Scott, whose drive for perfection resulted at times in double-digit takes.[37]

Development

Interest in adapting Philip K. Dick's novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? developed shortly after its 1968 publication. Director Martin Scorsese was interested in filming the novel, but never optioned it.[38] Producer Herb Jaffe optioned it in the early 1970s, but Dick was unimpressed with the screenplay written by Herb's son Robert: "Jaffe's screenplay was so terribly done ... Robert flew down to Santa Ana to speak with me about the project. And the first thing I said to him when he got off the plane was, 'Shall I beat you up here at the airport, or shall I beat you up back at my apartment?'"[39]

The screenplay by Hampton Fancher was optioned in 1977.[40] Producer Michael Deeley became interested in Fancher's draft and convinced director Ridley Scott to film it. Scott had previously declined the project, but after leaving the slow production of Dune, wanted a faster-paced project to take his mind off his older brother's recent death.[41] He joined the project on February 21, 1980, and managed to push up the promised Filmways financing from US$13 million to $15 million. Fancher's script focused more on environmental issues and less on issues of humanity and religion, which are prominent in the novel and Scott wanted changes. Fancher found a cinema treatment by William S. Burroughs for Alan E. Nourse's novel The Bladerunner (1974), titled Blade Runner (a movie).[nb 2] Scott liked the name, so Deeley obtained the rights to the titles.[42] Eventually he hired David Peoples to rewrite the script and Fancher left the job over the issue on December 21, 1980, although he later returned to contribute additional rewrites.[43]

Having invested over $2.5 million in pre-production,[44] as the date of commencement of principal photography neared, Filmways withdrew financial backing. In ten days Deeley had secured $21.5 million in financing through a three-way deal between The Ladd Company (through Warner Bros.), the Hong Kong-based producer Sir Run Run Shaw and Tandem Productions.[45]

Dick became concerned that no one had informed him about the film's production, which added to his distrust of Hollywood.[46] After Dick criticized an early version of Fancher's script in an article written for the Los Angeles Select TV Guide, the studio sent Dick the Peoples rewrite.[47] Although Dick died shortly before the film's release, he was pleased with the rewritten script and with a 20-minute special effects test reel that was screened for him when he was invited to the studio. Despite his well-known skepticism of Hollywood in principle, Dick enthused to Scott that the world created for the film looked exactly as he had imagined it.[30] He said, "I saw a segment of Douglas Trumbull's special effects for Blade Runner on the KNBC-TV news. I recognized it immediately. It was my own interior world. They caught it perfectly." He also approved of the film's script, saying, "After I finished reading the screenplay, I got the novel out and looked through it. The two reinforce each other, so that someone who started with the novel would enjoy the movie and someone who started with the movie would enjoy the novel."[48] The motion picture was dedicated to Dick.[49] Principal photography of Blade Runner began on March 9, 1981, and ended four months later.[50]

In 1992, Ford revealed, "Blade Runner is not one of my favorite films. I tangled with Ridley."[51] Apart from friction with the director, Ford also disliked the voiceovers: "When we started shooting it had been tacitly agreed that the version of the film that we had agreed upon was the version without voiceover narration. It was a f**king [sic] nightmare. I thought that the film had worked without the narration. But now I was stuck re-creating that narration. And I was obliged to do the voiceovers for people that did not represent the director's interests."[28] "I went kicking and screaming to the studio to record it."[52] The narration monologues were written by an uncredited Roland Kibbee.[53]

In 2006, Scott was asked "Who's the biggest pain in the arse you've ever worked with?", he replied: "It's got to be Harrison ... he'll forgive me because now I get on with him. Now he's become charming. But he knows a lot, that's the problem. When we worked together it was my first film up and I was the new kid on the block. But we made a good movie."[54] Ford said of Scott in 2000: "I admire his work. We had a bad patch there, and I'm over it."[55] In 2006 Ford reflected on the production of the film saying: "What I remember more than anything else when I see Blade Runner is not the 50 nights of shooting in the rain, but the voiceover ... I was still obliged to work for these clowns that came in writing one bad voiceover after another."[56] Ridley Scott confirmed in the summer 2007 issue of Total Film that Harrison Ford contributed to the Blade Runner Special Edition DVD, and had already recorded his interviews. "Harrison's fully on board", said Scott.[57]

The Bradbury Building in downtown Los Angeles served as a filming location, and a Warner Bros. backlot housed the 2019 Los Angeles street sets. Other locations included the Ennis-Brown House and the 2nd Street Tunnel. Test screenings resulted in several changes, including adding a voice-over, a happy ending, and the removal of a Holden hospital scene. The relationship between the filmmakers and the investors was difficult, which culminated in Deeley and Scott being fired but still working on the film.[58] Crew members created T-shirts during filming saying, "Yes Guv'nor, My Ass" that mocked Scott's unfavorable comparison of U.S. and British crews; Scott responded with a T-shirt of his own, "Xenophobia Sucks" making the incident known as the T-shirt war.[59][60]

Design

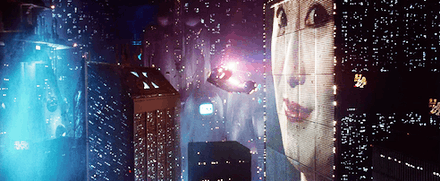

Ridley Scott credits Edward Hopper's painting Nighthawks and the French science fiction comics magazine Métal Hurlant, to which the artist Jean "Moebius" Giraud contributed, as stylistic mood sources.[61] He also drew on the landscape of "Hong Kong on a very bad day"[62] and the industrial landscape of his one-time home in northeast England.[63] The visual style of the movie is influenced by the work of futurist Italian architect Antonio Sant'Elia.[64] Scott hired Syd Mead as his concept artist; like Scott, he was influenced by Métal Hurlant.[65] Moebius was offered the opportunity to assist in the pre-production of Blade Runner, but he declined so that he could work on René Laloux's animated film Les Maîtres du temps – a decision that he later regretted.[66] Production designer Lawrence G. Paull and art director David Snyder realized Scott's and Mead's sketches. Douglas Trumbull and Richard Yuricich supervised the special effects for the film, and Mark Stetson served as chief model maker.[67]

Blade Runner has numerous deep similarities to Fritz Lang's Metropolis, including a built-up urban environment, in which the wealthy literally live above the workers, dominated by a huge building – the Stadtkrone Tower in Metropolis and the Tyrell Building in Blade Runner. Special effects supervisor David Dryer used stills from Metropolis when lining up Blade Runner's miniature building shots.[68]

The extended end scene in the original theatrical release shows Rachael and Deckard traveling into daylight with pastoral aerial shots filmed by director Stanley Kubrick. Ridley Scott contacted Kubrick about using some of his surplus helicopter aerial photography from The Shining.[69][70][71]

Spinner

"Spinner" is the generic term for the fictional flying cars used in the film. A spinner can be driven as a ground-based vehicle, and take off vertically, hover, and cruise much like vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) aircraft. They are used extensively by the police as patrol cars, and wealthy people can also acquire spinner licenses.[72] The vehicle was conceived and designed by Syd Mead who described the spinner as an "aerodyne" – a vehicle which directs air downward to create lift, though press kits for the film stated that the spinner was propelled by three engines: "conventional internal combustion, jet, and anti-gravity"[73] A spinner is on permanent exhibit at the Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame in Seattle, Washington.[74] Mead's conceptual drawings were transformed into 25 vehicles by automobile customizer Gene Winfield; at least two were working ground vehicles, while others were light-weight mockups for crane shots and set decoration for street shots.[75] Two of them ended up at Disney World in Orlando, Florida, but were later destroyed, and a few others remain in private collections.[75]

Voigt-Kampff machine

The Voigt-Kampff machine is a fictional interrogation tool, originating from the novel. The Voigt-Kampff is a polygraph-like machine used by blade runners to determine whether an individual is a replicant. It measures bodily functions such as respiration, blush response, heart rate and eye movement in response to questions dealing with empathy.[76] (Tyrell states: "Capillary dilation of the so-called blush response? Fluctuation of the pupil? Involuntary dilation of the iris?") In the film, two replicants – Leon and Rachael – take the test. Deckard tells Tyrell that it usually takes 20 to 30 cross-referenced questions to distinguish a replicant; in contrast with the book, where it is stated it only takes six or seven questions to make a determination. In the film, it takes more than a hundred questions to determine that Rachael is a replicant.

Music

The Blade Runner soundtrack by Vangelis is a dark melodic combination of classic composition and futuristic synthesizers which mirrors the film-noir retro-future envisioned by Ridley Scott. Vangelis, fresh from his Academy Award-winning score for Chariots of Fire,[77] composed and performed the music on his synthesizers.[78] He also made use of various chimes and the vocals of collaborator Demis Roussos.[79] Another memorable sound is the haunting tenor sax solo "Love Theme" by British saxophonist Dick Morrissey, who performed on many of Vangelis's albums. Ridley Scott also used "Memories of Green" from the Vangelis album See You Later, an orchestral version of which Scott would later use in his film Someone to Watch Over Me.[80]

Along with Vangelis' compositions and ambient textures, the film's soundscape also features a track by the Japanese ensemble Nipponia – "Ogi no Mato" or "The Folding Fan as a Target" from the Nonesuch Records release Traditional Vocal and Instrumental Music – and a track by harpist Gail Laughton from "Harps of the Ancient Temples" on Laurel Records.[81]

Despite being well received by fans and critically acclaimed and nominated in 1983 for a BAFTA and Golden Globe as best original score, and the promise of a soundtrack album from Polydor Records in the end titles of the film, the release of the official soundtrack recording was delayed for over a decade. There are two official releases of the music from Blade Runner. In light of the lack of a release of an album, the New American Orchestra recorded an orchestral adaptation in 1982 which bore little resemblance to the original. Some of the film tracks would, in 1989, surface on the compilation Vangelis: Themes, but not until the 1992 release of the Director's Cut version would a substantial amount of the film's score see commercial release.[79]

These delays and poor reproductions led to the production of many bootleg recordings over the years. A bootleg tape surfaced in 1982 at science fiction conventions and became popular given the delay of an official release of the original recordings, and in 1993 "Off World Music, Ltd" created a bootleg CD that would prove more comprehensive than Vangelis' official CD in 1994.[79] A set with three CDs of Blade Runner-related Vangelis music was released in 2007. Titled Blade Runner Trilogy, the first disc contains the same tracks as the 1994 official soundtrack release, the second features previously unreleased music from the movie, and the third disc is all newly composed music from Vangelis, inspired by, and in the spirit of the movie.[82]

Special effects

The film's special effects are generally recognized to be among the best of all time,[83][84][85] using the available (non-digital) technology to the fullest. In addition to matte paintings and models, the techniques employed included multipass exposures. In some scenes, the set was lit, shot, the film rewound, and then rerecorded over with different lighting. In some cases this was done 16 times in all. The cameras were frequently motion controlled using computers.[84] Many effects used techniques which had been developed during the production of Close Encounters of the Third Kind.[86]

Release

Blade Runner was released in 1,290 theaters on June 25, 1982. That date was chosen by producer Alan Ladd Jr. because his previous highest-grossing films (Star Wars and Alien) had a similar opening date (May 25) in 1977 and 1979, making the 25th of the month his "lucky day".[87] Blade Runner grossed reasonably good ticket sales in its opening weekend; earning $6.1 million during its first weekend in theaters.[88] The film was released close to other major science-fiction and fantasy releases such as The Thing, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Conan the Barbarian and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, which affected its commercial success.[89]

Critical reception

Initial reactions among film critics were mixed. Some wrote that the plot took a back seat to the film's special effects, and did not fit the studio's marketing as an action/adventure movie. Others acclaimed its complexity and predicted it would stand the test of time.[90] Negative criticism in the United States cited its slow pace.[91] Sheila Benson from the Los Angeles Times called it "Blade Crawler", and Pat Berman in The State and Columbia Record described it as "science fiction pornography".[92] Pauline Kael praised Blade Runner as worthy of a place in film history for its distinctive sci-fi vision, yet criticized the film's lack of development in "human terms".[93]

Academics began writing analyses of the film almost as soon as it was released,[94] and the boom in home video formats helped establish a growing cult around the film,[95] which scholars have dissected for its dystopic aspects, its questions regarding "authentic" humanity, its ecofeminist aspects,[96] and its use of conventions from multiple genres.[97] Popular culture began to reassess its impact as a classic several years after it was released.[98][99][100] Roger Ebert praised the visuals of both the original and the Director's Cut versions and recommended it for that reason; however, he found the human story clichéd and a little thin.[29] He later added The Final Cut to his "Great Movies" list.[101] Critic Chris Rodley and Janet Maslin theorized that Blade Runner changed cinematic and cultural discourse through its image repertoire, and subsequent influence on films.[102] In 2012, Time film critic Richard Corliss surgically analyzed the durability, complexity, screenplay, sets and production dynamics from a personal, three-decade perspective.[103] On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, Blade Runner holds an approval rating of 90% based on 108 reviews, with an average rating of 8.5/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "Misunderstood when it first hit theaters, the influence of Ridley Scott's mysterious, neo-noir Blade Runner has deepened with time. A visually remarkable, achingly human sci-fi masterpiece."[104] Metacritic, another review aggregator, assigned the film a weighted average score of 89 out of 100, based on 11 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[105] Denis Villeneuve, who directed the sequel, Blade Runner 2049, cites the film as a huge influence for him and many others.[100]

Accolades

Blade Runner won or received nominations for the following awards:[106]

Versions

Several versions of Blade Runner have been shown. The original workprint version (1982, 113 minutes) was shown for audience test previews in Denver and Dallas in March 1982. Negative responses to the previews led to the modifications resulting in the U.S. theatrical version.[107][108] The workprint was shown as a director's cut without Scott's approval at the Los Angeles Fairfax Theater in May 1990, at an AMPAS showing in April 1991, and in September and October 1991 at the Los Angeles NuArt Theater and the San Francisco Castro Theatre.[109] Positive responses pushed the studio to approve work on an official director's cut.[110] A San Diego Sneak Preview was shown only once, in May 1982, and was almost identical to the U.S. theatrical version but contained three extra scenes not shown in any other version, including the 2007 Final Cut.[111]

Two versions were shown in the film's 1982 theatrical release: the U.S. theatrical version (117 minutes),[1] known as the original version or Domestic Cut (released on Betamax, CED Videodisc and VHS in 1983, and on LaserDisc in 1987), and the International Cut (117 minutes), also known as the "Criterion Edition" or "uncut version", which included more violent action scenes than the U.S. version. Although initially unavailable in the U.S. and distributed in Europe and Asia via theatrical and local Warner Home Video Laserdisc releases, the International Cut was later released on VHS and Criterion Collection Laserdisc in North America, and re-released in 1992 as a "10th Anniversary Edition".[112]

Ridley Scott's Director's Cut (1991, 116 minutes)[113] was made available on VHS and Laserdisc in 1993, and on DVD in 1997. Significant changes from the theatrical version include the removal of Deckard's voice-over; the re-insertion of the unicorn sequence, and the removal of the studio-imposed happy ending. Scott provided extensive notes and consultation to Warner Bros. through film preservationist Michael Arick, who was put in charge of creating the Director's Cut.[114] Scott's The Final Cut (2007, 117 minutes)[115] was released by Warner Bros. theatrically on October 5, 2007, and subsequently released on DVD, HD DVD, and Blu-ray Disc in December 2007.[116] This is the only version over which Scott had complete artistic and editorial control.[114]

| Year | Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | Fantasporto | International Fantasy Film Award | Best Film – Ridley Scott (Director's Cut) | Nominated |

| 1994 | Saturn Award | Best Genre Video Release | Blade Runner (Director's Cut) | Nominated |

| 2008 | Saturn Award | Best DVD Special Edition Release | Blade Runner (5-Disc Ultimate Collector's Edition) | Won |

Legacy

Cultural impact

While not initially a success with North American audiences, Blade Runner was popular internationally and garnered a cult following.[117] The film's dark style and futuristic designs have served as a benchmark and its influence can be seen in many subsequent science fiction films, video games, anime, and television programs.[8] For example, Ronald D. Moore and David Eick, the producers of the re-imagining of Battlestar Galactica, have both cited Blade Runner as one of the major influences for the show.[118]

The film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry in 1993 and is frequently taught in university courses.[119] In 2007, it was named the second-most visually influential film of all time by the Visual Effects Society.[120] The film has also been the subject of parody, such as the comics Blade Bummer by Crazy comics,[121] Bad Rubber by Steve Gallacci,[122] and the Red Dwarf 2009 three-part miniseries "Back to Earth".[123][124]

Blade Runner continues to reflect modern trends and concerns, and an increasing number of critics consider it one of the greatest science fiction films of all time.[125] It was voted the best science fiction film ever made in a 2004 poll of 60 eminent world scientists.[126] Blade Runner is also cited as an important influence to both the style and story of the Ghost in the Shell film series, which itself has been highly influential to the future-noir genre.[127][128] Blade Runner has been very influential to the cyberpunk movement.[129][130][131][132] It also influenced the cyberpunk derivative biopunk, which revolves around biotechnology and genetic engineering.[133][134]

The dialogue and music in Blade Runner has been sampled in music more than any other film of the 20th century.[135][nb 3]

The 2009 album I, Human by Singaporean band Deus Ex Machina makes numerous references to the genetic engineering and cloning themes from the film, and even features a track titled "Replicant".[136]

Blade Runner is cited as a major influence on Warren Spector,[137] designer of the video game Deus Ex, which displays evidence of the film's influence in both its visual rendering and plot. Indeed, the film's look – and in particular its overall darkness, preponderance of neon lights, and opaque visuals – are easier to render than complicated backdrops, making it a popular reference point for video game designers.[138][139] It has influenced adventure games such as the 2012 graphical text adventure Cypher;[140] Rise of the Dragon;[141][142] Snatcher;[142][143] the Tex Murphy series;[144] Beneath a Steel Sky;[145] Flashback: The Quest for Identity;[142] Bubblegum Crisis (and its original anime films);[146][147] the role-playing game Shadowrun;[142] the first-person shooter Perfect Dark;[148] the shooter game Skyhammer;[149][150] and the Syndicate series of video games.[151][152]

The logos of Atari, Bell, Coca-Cola, Cuisinart, and Pan Am, all market leaders at the time, were prominently displayed as product placement in the film, and all experienced setbacks after the film's release,[153] leading to suggestions of a Blade Runner curse.[154] Coca-Cola and Cuisinart recovered, and Tsingtao beer was also featured in the film and was more successful after the film than before.[155]

Media recognitions for Blade Runner include:

| Year | Presenter | Title | Rank | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | The Village Voice | 100 Best Films of the 20th Century | 94 | [156] |

| 2002 | Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) | Top 100 Sci-fi Films of the Past 100 Years | 2 | [157] |

| Sight & Sound | Sight & Sound Top Ten Poll 2002 | 45 | [158] | |

| 50 Klassiker, Film | None | [159] | ||

| 2003 | 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die | [160] | ||

| Entertainment Weekly | The Top 50 Cult Movies | 9 | [161] | |

| 2004 | The Guardian, Scientists | Top 10 Sci-fi Films of All Time | 1 | [162][163][164] |

| 2005 | Total Film's Editors | 100 Greatest Movies of All Time | 47 | [165] |

| Time Magazine's Critics | "All-Time 100" Movies | None | [166][167][168] | |

| 2008 | New Scientist | All-time favorite science fiction film (readers and staff) | 1 | [169][170] |

| Empire | The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time | 20 | [171] | |

| 2010 | IGN | Top 25 Sci-Fi Movies of All Time | 1 | [172] |

| Total Film | 100 Greatest Movies of All Time | None | [173] | |

| 2012 | Sight & Sound | Sight & Sound 2012 critics top 250 films | 69 | [174] |

| Sight & Sound | Sight & Sound 2012 directors top 100 films | 67 | [175] | |

| 2017 | Empire | The 100 Greatest Movies Of All Time | 13 | [176] |

American Film Institute recognition

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills – No. 74

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – No. 97

- AFI's 10 Top 10 – No. 6 Science Fiction Film

In other media

Before filming began, Cinefantastique magazine commissioned Paul M. Sammon to write a special issue about Blade Runner's production which became the book Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner.[177] The book chronicles Blade Runner's evolution, focusing on film-set politics, especially the British director's experiences with his first American film crew; of which producer Alan Ladd, Jr. has said, "Harrison wouldn't speak to Ridley and Ridley wouldn't speak to Harrison. By the end of the shoot Ford was 'ready to kill Ridley', said one colleague. He really would have taken him on if he hadn't been talked out of it."[178] Future Noir has short cast biographies and quotations about their experiences, and photographs of the film's production and preliminary sketches. A second edition of Future Noir was published in 2007, and additional materials not in either print edition have been published online.[179]

Philip K. Dick refused a $400,000 offer to write a Blade Runner novelization, saying: "[I was] told the cheapo novelization would have to appeal to the twelve-year-old audience" and it "would have probably been disastrous to me artistically". He added, "That insistence on my part of bringing out the original novel and not doing the novelization – they were just furious. They finally recognized that there was a legitimate reason for reissuing the novel, even though it cost them money. It was a victory not just of contractual obligations but of theoretical principles."[48] Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? was eventually reprinted as a tie-in, with the film poster as a cover and the original title in parentheses below the Blade Runner title.[180] Additionally, a novelization of the movie entitled Blade Runner: A Story of the Future by Les Martin was released in 1982.[181] Archie Goodwin scripted the comic book adaptation, A Marvel Super Special: Blade Runner, published in September 1982, which was illustrated by Al Williamson, Carlos Garzon, Dan Green, and Ralph Reese, and lettered by Ed King.[182]

There are two video games based on the film, both titled Blade Runner: one from 1985, an action-adventure side-scroller for Commodore 64, Sinclair ZX Spectrum, and Amstrad CPC by CRL Group PLC, marked as based on the music by Vangelis rather than the film itself (due to licensing issues); and another from 1997, a point-and-click adventure by Westwood Studios. The 1997 video game featured new characters and branching storylines based on the Blade Runner world. Eldon Tyrell, Gaff, Leon, Rachael, Chew, and J. F. Sebastian appear, and their voice files are recorded by the original actors.[183] The player assumes the role of McCoy, another replicant-hunter working at the same time as Deckard.[138][139]

The PC game featured a non-linear plot, non-player characters that each ran in their own independent AI, and an unusual pseudo-3D engine (which eschewed polygonal solids in favor of voxel elements) that did not require the use of a 3D accelerator card to play the game.[184]

The television film (and later series) Total Recall 2070 was initially planned as a spin-off of the film Total Recall (based on Philip K. Dick's short story "We Can Remember It for You Wholesale"), but was produced as a hybrid of Total Recall and Blade Runner.[185] Many similarities between Total Recall 2070 and Blade Runner were noted, as well as apparent influences on the show from Isaac Asimov's The Caves of Steel and the TV series Holmes & Yoyo.[186]

Documentaries

The film has been the subject of several documentaries.

- On the Edge of Blade Runner (2000, 55 minutes)

- was directed by Andrew Abbott and hosted/written by Mark Kermode. Interviews with production staff, including Scott, give details of the creative process and the turmoil during preproduction. Insights into Philip K. Dick and the origins of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? are provided by Paul M. Sammon and Hampton Fancher.[58]

- Future Shocks (2003, 27 minutes)

- is a documentary by TVOntario.[187] It includes interviews with executive producer Bud Yorkin, Syd Mead, and the cast, and commentary by science fiction author Robert J. Sawyer and from film critics.

- Dangerous Days: Making Blade Runner (2007, 213 minutes)

- is a documentary directed and produced by Charles de Lauzirika for The Final Cut version of the film. Its source material comprises more than 80 interviews, including extensive conversations with Ford, Young, and Scott.[188] The documentary is presented in eight chapters, with each of the first seven covering a portion of the filmmaking process. The final chapter examines Blade Runner's controversial legacy.[189]

- All Our Variant Futures: From Workprint to Final Cut (2007, 29 minutes)

- produced by Paul Prischman, appears on the Blade Runner Ultimate Collector's Edition and provides an overview of the film's multiple versions and their origins, as well as detailing the seven-year-long restoration, enhancement and remastering process behind The Final Cut.[116]

Sequels and related media

A direct sequel was released in 2017, titled Blade Runner 2049, with Ryan Gosling in the starring role.[190][191] The film entered production in mid-2016, is set decades after the first film,[192] and saw Harrison Ford reprise his role as Rick Deckard.

Dick's friend K. W. Jeter wrote three authorized Blade Runner novels that continue Rick Deckard's story, attempting to resolve the differences between the film and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?[193] These are Blade Runner 2: The Edge of Human (1995), Blade Runner 3: Replicant Night (1996), and Blade Runner 4: Eye and Talon (2000)

Blade Runner cowriter David Peoples wrote the 1998 action film Soldier, which he referred to as a "sidequel" or spiritual successor to the original film; the two are set in a shared universe.[194] A bonus feature on the Blu-ray for Prometheus, the 2012 film by Scott set in the Alien and Predator universe, states that Eldon Tyrell, CEO of the Blade Runner Tyrell Corporation, was the mentor of Guy Pearce's character Peter Weyland.[195]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Sebastian's death was never shot because of concerns over too much violence in the film.[7]

- ↑ Some editions of Nourse's novel use the two-word spacing Blade Runner, as does the Burroughs book.

- ↑ See also Tears in rain monologue § Music.

References

- 1 2 "Blade Runner". British Board of Film Classification. May 27, 1982. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Blade Runner". AFI.com. American Film Institute. Archived from the original on November 6, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Blade Runner". BFI.org. British Film Institute. Archived from the original on December 6, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Blade Runner (1982)". British Film Institute. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ↑ "Blade Runner – Box Office Data, DVD and Blu-ray Sales, Movie News, Cast and Crew Information". The Numbers. Archived from the original on December 16, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ↑ "Blade Runner: The Final Cut (2007)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on April 12, 2014. Retrieved April 12, 2014.

- ↑ Sammon, p. 175

- 1 2 Barlow, Aaron "Reel Toads and Imaginary Cities: Philip K. Dick, Blade Runner and the Contemporary Science Fiction Movie" in Brooker, pp. 43–58

- ↑ Jermyn, Deborah "The Rachael Papers: In Search of Blade Runners Femme Fatale" in Brooker, pp. 159–172

- ↑ Jenkins, Mary (1997), "The Dystopian World of Blade Runner: An Ecofeminist Perspective", Trumpeter, 14 (4), retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Kerman, Judith B. "Post-Millennium Blade Runner" in Brooker, pp. 31–39

- 1 2 Alessio, Dominic "Redemption, 'Race', Religion, Reality and the Far-Right: Science Fiction Film Adaptations of Philip K. Dick" in Brooker, pp. 59–76

- ↑ Sammon, p. 384

- ↑ Barber, Lynn (January 6, 2002), "Scott's Corner", The Observer, London, archived from the original on July 20, 2008, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Leaver, Tama (1997), Post-Humanism and Ecocide in William Gibson's Neuromancer and Ridley Scott's Blade Runner, archived from the original on July 3, 2013, retrieved July 27, 2011 – via The Cyberpunk Project

- ↑ Bukatman, pp. 9–11

- ↑ Heldreth, Leonard G. "The Cutting Edges of Blade Runner" in Kerman (1991), p. 44

- ↑ Gwaltney, Marilyn. "Androids as a Device for Reflection on Personhood" in Kerman (1991), pp. 32–39

- ↑ Bukatman, pp. 80–83

- ↑ Sammon, p. 362

- ↑ Peary, Danny, ed. (1984), "Directing Alien and Blade Runner: An Interview with Ridley Scott", Omni's Screen Flights, Screen Fantasies: The Future According to Science Fiction, Omni magazine / Doubleday, pp. 293–302, ISBN 978-0-385-19202-6

- ↑ Kaplan, Fred (September 30, 2007), "A Cult Classic Restored, Again", The New York Times, archived from the original on February 5, 2018, retrieved July 27, 2011,

The film's theme of dehumanization has also been sharpened. What has been a matter of speculation and debate is now a certainty: Deckard, the replicant-hunting cop, is himself a replicant. Mr. Scott confirmed this: 'Yes, he's a replicant. He was always a replicant.'

- ↑ Blade Runner riddle solved, BBC News, July 9, 2000, archived from the original on April 6, 2014, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Brooker, Peter "Imagining the Real: Blade Runner and Discourses on the Postmetropolis" in Brooker, pp. 9, 222

- ↑ Bukatman, p. 83

- ↑ Hills, Matt "Academic Textual Poachers: Blade Runner as Cult Canonical Film" in Brooker, pp. 124–141

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Dangerous Days: Making Blade Runner [documentary]", Blade Runner: The Final Cut (DVD), Warner Bros., 2007 [1982]

- 1 2 "Ford: 'Blade Runner Was a Nightmare'", Moono.com, July 5, 2007, archived from the original on February 24, 2012, retrieved July 27, 2011

- 1 2 Ebert, Roger (September 11, 1992), "Blade Runner: Director's Cut [review]", RogerEbert.com, archived from the original on March 4, 2013, retrieved July 27, 2011

- 1 2 Sammon, p. 284

- ↑ Hauer, Rutger (February 7, 2001). "Chatroom Transcripts: Live Chat February 7, 2001". RutgerHauer.org (Interview). Archived from the original on January 24, 2012. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ↑ Sammon, pp. 92–93

- 1 2 Sammon, pp. 115–116

- ↑ Bukatman, p. 72

- ↑ Sammon, p. 170

- ↑ Sanderson, William (October 5, 2000). "A Chat with William Sanderson". BladeZone (Interview). Interviewed by Brinkley, Aaron. Archived from the original on April 28, 2014. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ↑ Sammon, p. 150

- ↑ Bukatman, p. 13; Sammon, p. 23

- ↑ Dick quoted in Sammon, p. 23

- ↑ Sammon, pp. 23–30

- ↑ Sammon, pp. 43–49

- ↑ Abraham Riesman, "Digging Into the Odd History of Blade Runner's Title", Vulture, October 4, 2017. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- ↑ Sammon, pp. 49–63

- ↑ Sammon, p. 49

- ↑ Bukatman, pp. 18–19; Sammon, pp. 64–67

- ↑ Sammon, pp. 63–64

- ↑ Sammon, pp. 67–69

- 1 2 Boonstra, John (June 1982), "A final interview with science fiction's boldest visionary, who talks candidly about Blade Runner, inner voices and the temptations of Hollywood", Rod Serling's the Twilight Zone Magazine, 2 (3), pp. 47–52, archived from the original on May 28, 2013, retrieved July 27, 2011 – via Philip K. Dick

- ↑ Blade Runner film, dedication after credits, 1:51:30

- ↑ Sammon, p. 98

- ↑ Sammon, p. 211

- ↑ Sammon, p. 296

- ↑ Pahle, Rebecca (August 28, 2015), "10 Fascinating Facts About Blade Runner", Mental Floss, archived from the original on August 29, 2015, retrieved March 24, 2015

- ↑ Carnevale, Rob (September 2006), Getting Direct with Directors: Ridley Scott, BBC News, archived from the original on April 13, 2014, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Kennedy, Colin (November 2000), "And beneath lies, the truth", Empire (137), p. 76

- ↑ "In Conversation with Harrison Ford", Empire (202), p. 140, April 2006

- ↑ Smith, Neil (Summer 2007), "The Total Film Interview", Total Film (130)

- 1 2 Ingels, Nicklas, "On the Edge of Blade Runner", Los Angeles, 2019, archived from the original on April 7, 2014, retrieved July 27, 2011 – via Tyrell-Corporation.pp.se

- ↑ Sammon, p. 218

- ↑ Davis, Cindy (November 8, 2011), "Mindhole Blowers: 20 facts about Blade Runner that might leave you questioning Ridley Scotts humanity", Pajiba.com, archived from the original on August 2, 2014, retrieved September 21, 2014

- ↑ Sammon, p. 74

- ↑ Wheale, Nigel (1995), The Postmodern Arts: An Introductory Reader, Routledge, p. 107, ISBN 978-0-415-07776-7, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Monahan, Mark (September 20, 2003), "Director Maximus", The Daily Telegraph, London, archived from the original on June 21, 2008, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ "Irish Arts Review", Irish Arts Review, retrieved September 27, 2014

- ↑ Sammon, p. 53

- ↑ Giraud, Jean (1988), Moebius 4: The Long Tomorrow & Other SF Stories, Marvel Comics, ISBN 978-0-87135-281-1

- ↑ Failes, Ian (October 2, 2017). "The Miniature Models of BLADE RUNNER". VFX Voice. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ↑ Bukatman, pp. 61–63; Sammon, p. 111

- ↑ "Quentin Tarantino, Ridley Scott, Danny Boyle, & More Directors on THR's Roundtables I". The Hollywood Reporter. 2016. Archived from the original on January 6, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2018 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Eggersten, Chris (December 10, 2015). "Ridley Scott: I used footage from Kubrick's The Shining in Blade Runner". Hitfix. Uproxx. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- ↑ Howard, Annie. "Ridley Scott Reveals Stanley Kubrick Gave Him Footage from The Shining for Blade Runner Ending". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 14, 2016.

- ↑ Sammon, pp. 79–80

- ↑ "The Top 40 Cars from Feature Films: 30. Police Spinner", ScreenJunkies, March 30, 2010, archived from the original on April 4, 2014, retrieved July 27, 2011,

though press kits for the film stated that the spinner was propelled by three engines: "conventional internal combustion, jet and anti-gravity".

- ↑ "Experience Music Project / Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame (EMP/SFM)" (PDF). Museum of Pop Culture. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 24, 2011.

- 1 2 Winfield, Gene. "Deconstructing the Spinner". BladeZone (Interview). Interviewed by Willoughby, Gary. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ↑ Sammon, pp. 106–107

- ↑ Vangelis, "Blade Runner – Scoring the music", NemoStudios.co.uk, archived from the original on October 19, 2013, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Sammon, pp. 271–274

- 1 2 3 Sammon, pp. 419–423

- ↑ Larsen, Peter (2007), Film music, London: Reaktion Books, p. 179, ISBN 978-1-86189-341-3

- ↑ Sammon, p. 424

- ↑ Orme, Mike (February 7, 2008), "Album Review: Vangelis: Blade Runner Trilogy: 25th Anniversary", Pitchfork, archived from the original on October 29, 2013, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ "10 Pre-2000 Movies with Special Effects That Still Hold up Today", WhatCulture.com, archived from the original on May 18, 2015

- 1 2 Savage, Adam, "Blade Runner at 25: Why the Sci-Fi F/X Are Still Unsurpassed", Popular Mechanics, archived from the original on April 2, 2015

- ↑ "Los Angeles 2019 (Blade Runner) – Cinema's Greatest Effects Shots Picked by Hollywood's Top VFX Specialists", Empire, archived from the original on May 18, 2015

- ↑ "Blade Runner: Spinner Vehicles", DouglasTrumbull.com, Trumbull Ventures, 2010, archived from the original on July 4, 2015, retrieved September 21, 2015

- ↑ Sammon, p. 309

- ↑ Harmetz, Aljean (June 29, 1982), "E.T. May Set Sales Record", The New York Times, Section C, Cultural Desk, page 9

- ↑ Sammon, p. 316

- ↑ Sammon, pp. 313–315

- ↑ Hicks, Chris (September 11, 1992), "Movie review: Blade Runner", Deseret News, archived from the original on April 7, 2014, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Quoted in Sammon, p. 313 and p. 314, respectively

- ↑ Kael, Pauline (1984), Taking It All In, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, pp. 360–365, ISBN 978-0-03-069361-8

- ↑ Williams, Douglas E. (October 1988), "Ideology as Dystopia: An Interpretation of "Blade Runner"" (PDF), International Political Science Review, 9 (4), pp. 381–394, JSTOR 1600763, archived (PDF) from the original on July 8, 2016, retrieved October 13, 2015

- ↑ Dalton, Stephen (October 26, 2016). "Blade Runner: anatomy of a classic". British Film Institute.

- ↑ Jenkins, Mary (1997), "The Dystopian World of Blade Runner: An Ecofeminist Perspective", Trumpeter, 14 (4), retrieved October 13, 2015

- ↑ Doll, Susan; Faller, Greg (1986), "Blade Runner and Genre: Film Noir and Science Fiction", Literature Film Quarterly, 14 (2), archived from the original on October 13, 2015, retrieved October 13, 2015

- ↑ Gray, Tim (June 24, 2017). "'Blade Runner' Turns 35: Ridley Scott's Unloved Film That Became a Classic". Variety.

- ↑ Shone, Tom (June 6, 2012), "Woman: The Other Alien in Alien", Slate, archived from the original on April 24, 2016

- 1 2 Jagernauth, Kevin (April 28, 2015), "Blade Runner Is Almost a Religion for Me: Denis Villeneuve Talks Directing the Sci-fi Sequel", IndieWire, archived from the original on October 1, 2015, retrieved October 12, 2015

- ↑ Ebert, Roger. "Blade Runner: The Final Cut Movie Review (1982)". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on June 27, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ↑ Rodley, Chris (1993), "Blade Runner: The Director's Cut", frieze, archived from the original on September 5, 2008, retrieved October 14, 2015

- ↑ Blade Runner at 30: Celebrating Ridley Scott's Dystopian Vision Archived December 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., Time, Richard Corliss, June 25, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ↑ "Blade Runner (1982)", Rotten Tomatoes, retrieved September 28, 2017

- ↑ "Blade Runner". Metacritic. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ↑ "Blade Runner", The New York Times, archived from the original on May 17, 2013, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Kaplan, Fred (September 30, 2007), "A Cult Classic Restored, Again", The New York Times, archived from the original on December 20, 2013, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Sammon, p. 289

- ↑ Bukatman, pp. 36–37; Sammon, pp. 334–340

- ↑ Bukatman, p. 37

- ↑ Sammon, pp. 306 and 309–311

- ↑ Sammon, pp. 326–329

- ↑ "Blade Runner [Director's Cut]". British Board of Film Classification. September 29, 1992. Archived from the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- 1 2 Sammon, pp. 353, 365

- ↑ "Blade Runner [The Final Cut]". British Board of Film Classification. October 12, 2007. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- 1 2 "Blade Runner: The Final Cut", The Digital Bits, July 26, 2007, archived from the original on February 22, 2014, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Sammon, pp. 318–329

- ↑ Moore, Ronald D.; Eick, David (February 21, 2008). "Battlestar Galactica Interview". Concurring Opinions (Interview). Interviewed by Daniel Solove, Deven Desai and David Hoffman. Archived from the original on October 3, 2011. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ↑ Rapold, Nicolas (October 2, 2007), "Aren't We All Just Replicants on the Inside?", The New York Sun, archived from the original on September 5, 2008, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ The Visual Effects Society Unveils '50 Most Influential Visual Effects Films of All Time' (PDF), Visual Effects Society, archived from the original (PDF) on June 4, 2012, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Kissell, Gerry, "Crazy: Blade Runner Parody", BladeZone, archived from the original on April 28, 2014, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Gallacci, Steven A., "Albedo #0", Grand Comics Database Project, "Bad Rubber" section, archived from the original on April 6, 2014, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Howard, Rob, "Red Dwarf: Back To Earth – This Weekend's Essential Viewing – NME Video Blog", NME, archived from the original on October 11, 2012, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Red Dwarf: Back to Earth – Director's Cut DVD 2009: Amazon.co.uk: Craig Charles, Danny John-Jules, Chris Barrie, Robert Llewellyn, Doug Naylor: DVD, Amazon.com, archived from the original on June 14, 2009, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Jha, Alok; Rogers, Simon; Rutherford, Adam (August 26, 2004), "'I've seen things...': Our expert panel votes for the top 10 sci-fi films", The Guardian, London, archived from the original on May 13, 2007, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Blade Runner tops scientist poll, BBC News, August 26, 2004, archived from the original on May 13, 2014, retrieved September 22, 2012

- ↑ Omura, Jim (September 16, 2004), "Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence", FPS Magazine, archived from the original on October 29, 2013, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Rose, Steve (October 19, 2009), "Hollywood is haunted by Ghost in the Shell", The Guardian, archived from the original on March 8, 2013, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Coplan, Amy; Davies, David (2015). Blade Runner. Routledge. ISBN 9781136231445. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ↑ Booker, M. Keith (2006). Alternate Americas: Science Fiction Film and American Culture. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780275983956. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ↑ Milner, Andrew (2005). Literature, Culture and Society. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415307857. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ↑ Brown, Steven T. (2016). Tokyo Cyberpunk: Posthumanism in Japanese Visual Culture. Springer. ISBN 9780230110069. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ↑ Evans, Josh (September 18, 2011). "What Is Biopunk?". ScienceFiction.com. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- ↑ Wohlsen, Marcus (2011). Biopunk: Solving Biotech's Biggest Problems in Kitchens and Garages. Current Publishing. ISBN 1617230022.

- ↑ Cigéhn, Peter (September 1, 2004), "The Top 1319 Sample Sources (version 60)", Sloth.org, archived from the original on October 27, 2013, retrieved July 27, 2011 – via Semimajor.net

- ↑ "Deus Ex Machina – I, Human Review", The Metal Crypt, February 22, 2010, archived from the original on April 7, 2014, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ "Gaming Gurus", Wired, 14 (4), April 1, 2006, archived from the original on September 3, 2013, retrieved August 28, 2009

- 1 2 Atkins, Barry "Replicating the Blade Runner" in Brooker, pp. 79–91

- 1 2 Tosca, Susana P. "Implanted Memories, or the Illusion of Free Action" in Brooker pp. 92–107

- ↑ Webster, Andrew (October 17, 2012), "Cyberpunk meets interactive fiction: The art of Cypher", The Verge, archived from the original on February 1, 2014, retrieved February 27, 2013

- ↑ "Rise of the Dragon", OldGames.sk, archived from the original on February 2, 2014, retrieved November 10, 2010

- 1 2 3 4 "Tracing Replicants: We examine Blade Runner's influence on games", 1Up, archived from the original on July 18, 2012, retrieved November 11, 2010

- ↑ "Blade Runner and Snatcher", AwardSpace.co.uk, archived from the original on July 25, 2013, retrieved November 10, 2010

- ↑ "The Top 10 Best Game Detectives". NowGamer. Archived from the original on March 16, 2012.

- ↑ "Beneath a Steel Sky", Softonic.com, archived from the original on October 19, 2013, retrieved November 10, 2010

- ↑ Lambie, Ryan, "Bubblegum Crisis 3D live-action movie on the way", Den of Geek, archived from the original on January 4, 2012, retrieved November 10, 2010

- ↑ "3D Live Action Bubblegum Crisis Movie Gets a Director and a Start Date", BleedingCool.com, archived from the original on April 7, 2014, retrieved November 10, 2010

- ↑ Retrospective: Perfect Dark, archived from the original on February 21, 2011, retrieved November 10, 2010

- ↑ Ripper, The (December 1994). "Europa!". GameFan. No. Volume 2, Issue 12. Shinno Media. p. 214.

- ↑ Robertson, Andy (June 2, 1996). "Skyhammer - Now here's a game that really soars!". ataritimes.com. Retrieved 2018-08-20.

- ↑ Schrank, Chuck, "Syndicate Wars: Review", Gamezilla PC Games, archived from the original on September 8, 2013, retrieved November 10, 2010 – via Lubie.org

- ↑ "Syndicate", HardcoreGaming101.net, archived from the original on January 1, 2014, retrieved November 10, 2010

- ↑ Mariman, Lukas; Chapman, Murray, eds. (December 2002), "Blade Runner: Frequently Asked Questions", alt.fan.blade-runner, 4.1, archived from the original on February 5, 2018, retrieved February 4, 2018 – via FAQs.CS.UU.nl

- ↑ Sammon, p. 104

- ↑ "The curse of Blade Runner's adverts". BBC Newsbeat. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ↑ Hoberman, J.; Village Voice Critics' Poll (2001), "100 Best Films of the 20th Century", The Village Voice, archived from the original on March 31, 2014, retrieved July 27, 2011 – via FilmSite.org

- ↑ "OFCS Top 100: Top 100 Sci-Fi Films", OFCS.org, Online Film Critics Society, June 12, 2002, archived from the original on March 13, 2012, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ "Sight & Sound Top Ten Poll 2002", Sight & Sound, British Film Institute, 2002, archived from the original on May 15, 2012, retrieved February 4, 2018 – via BFI.org.uk

- ↑ Schröder, Nicolaus (2002), 50 Klassiker, Film (in German), Gerstenberg, ISBN 978-3-8067-2509-4

- ↑ 1001 Movies to See Before You Die, July 22, 2002, archived from the original on May 28, 2014, retrieved February 4, 2011 – via 1001BeforeYouDie.com

- ↑ "Top 50 Cult Movies", Entertainment Weekly, May 23, 2003, archived from the original on March 31, 2014, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ "Top 10 sci-fi films", The Guardian, archived from the original on July 25, 2013, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Jha, Alok (August 26, 2004), "Scientists vote Blade Runner best sci-fi film of all time", The Guardian, archived from the original on March 8, 2013, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ "How we did it", The Guardian, August 26, 2004, archived from the original on July 26, 2013, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ "Film news: Who is the greatest?", Total Film, Future Publishing, October 24, 2005, archived from the original on January 23, 2014, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ "The Complete List – All-Time 100 Movies", Time, May 23, 2005, archived from the original on August 22, 2011, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ "All-Time 100 Movies", Time (magazine), February 12, 2005, archived from the original on August 31, 2011, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Corliss, Richard (February 12, 2005), "All-Time 100 Movies: Blade Runner (1982)", Time (magazine), archived from the original on March 8, 2011, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ George, Alison (November 12, 2008), "Sci-fi special: Your all-time favourite science fiction", New Scientist, archived from the original on April 6, 2014, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ George, Alison (October 1, 2008), "New Scientist's favourite sci-fi film", New Scientist, archived from the original on April 6, 2014, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ "Empire Features", Empire, archived from the original on October 14, 2013, retrieved July 26, 2011

- ↑ Pirrello, Phil; Collura, Scott; Schedeen, Jesse, "Top 25 Sci-Fi Movies of All Time", IGN.com, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ "Film Features: 100 Greatest Movies of All Time", Total Film, Future Publishing, archived from the original on December 22, 2013, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ "Sight & Sound 2012 critics top 250 films", Sight & Sound, British Film Institute, 2012, archived from the original on October 26, 2013, retrieved September 20, 2012 – via BFI.org

- ↑ "Sight & Sound 2012 directors top 100 films", Sight & Sound, British Film Institute, 2012, archived from the original on April 18, 2014, retrieved September 20, 2012 – via BFI.org

- ↑ "The 100 Greatest Movies", Empire, March 20, 2018

- ↑ Sammon, p. 1

- ↑ Shone, Tom (2004), Blockbuster, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-0-7432-3990-5

- ↑ "Future Noir: Lost Chapters", 2019: Off-World, archived from the original on June 24, 2001, retrieved February 4, 2018 – via Scribble.com

- ↑ Dick, Philip K. (2007), Blade Runner: (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?), Del Rey Books, p. 216, ISBN 978-0-345-35047-3, retrieved July 27, 2011 – via Google Books

- ↑ Marshall, Colin (September 14, 2015). "Hear Blade Runner, Terminator, Videodrome & Other 70s, 80s & 90s Movies as Novelized AudioBooks". Open Culture. Archived from the original on December 24, 2016.

- ↑ "Marvel Super Special #22". Grand Comics Database. Archived from the original on April 6, 2014.

- ↑ Mariman, Lukas; et al. (eds.), "The Blade Runner Game", BRMovie.com, archived from the original on July 14, 2008, retrieved August 10, 2010

- ↑ Bates, Jason (September 9, 1997), "Westwood's Blade Runner", PC Gamer, 4 (9), archived from the original on November 27, 2012, retrieved July 27, 2011 – via BladeZone

- ↑ Robb, Brian J. (2006), Counterfeit Worlds: Philip K. Dick on Film, Titan Books, pp. 200–225, ISBN 978-1-84023-968-3

- ↑ Platt, John (March 1, 1999), "A Total Recall spin-off that's an awful lot like Blade Runner", Science Fiction Weekly, 5 (9 [total issue #98]), archived from the original on January 15, 2008, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ "Future Shocks", TVO.org, TVOntario, Ontario Educational Communications Authority, archived from the original on December 24, 2014, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Fischer, Russ (February 8, 2007), "Interview: Charles de Lauzirika (Blade Runner)", CHUD.com, archived from the original on February 2, 2014, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Weitz, Scott (December 16, 2007), "Blade Runner – The Final Cut: 2-Disc Special Edition DVD Review", FilmEdge.net, archived from the original on May 17, 2013, retrieved July 27, 2011

- ↑ Goldberg, Matt (November 16, 2015), "Ryan Gosling Confirms He's in Blade Runner 2; Talks Shane Black's The Nice Guys", Collider, retrieved November 16, 2015

- ↑ Nudd, Tim. "Ryan Gosling Set to Join Harrison Ford in Blade Runner Sequel". People. Archived from the original on August 23, 2015.

- ↑ Foutch, Haleigh (January 25, 2016). "Blade Runner 2 Officially Starts Filming This July". Collider. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ↑ Gray, Christy "Originals and Copies: The Fans of Philip K. Dick, Blade Runner and K. W. Jeter" in Brooker, pp. 142–156

- ↑ Cinescape, September/October 1998 issue

- ↑ D'Alessandro, Anthony (August 31, 2017). "Blade Runner 2049 Prequel Short Connects Events to Original 1982 Film". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved October 3, 2017.

Bibliography

- Brooker, Will, ed. (2005). The Blade Runner Experience. London: Wallflower. ISBN 978-1-904764-30-4.

- Bukatman, Scott (1997). BFI Modern Classics: Blade Runner. London: British Film Institute. ISBN 978-0-85170-623-8.

- Kerman, Judith, ed. (1991). Retrofitting Blade Runner: Issues in Ridley Scott's Blade Runner and Philip K. Dick's Do Android's Dream of Electric Sheep?. Bowling Green University Popular Press. ISBN 978-0-87972-510-5.

- Macarthur, David (2017). "A Vision of Blindness: Bladerunner and Moral Redemption". Film Philosophy. Edinburgh University Press. 21 (3).

- Sammon, Paul M. (1996). Future Noir: the Making of Blade Runner. London: Orion Media. ISBN 978-0-06-105314-6.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Blade Runner |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blade Runner. |

- Official website

- Blade Runner at Box Office Mojo

- Blade Runner at Curlie (based on DMOZ)

- Blade Runner on IMDb

- Blade Runner at Metacritic

- Blade Runner at Rotten Tomatoes

- Blade Runner at the TCM Movie Database