Metropolis (1927 film)

| Metropolis | |

|---|---|

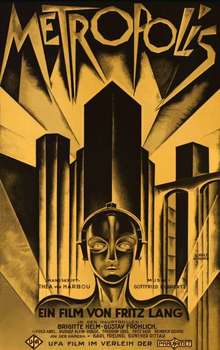

original 1927 theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Fritz Lang |

| Produced by | Erich Pommer |

| Screenplay by |

Thea von Harbou Fritz Lang (uncredited) |

| Based on |

Metropolis (1925 novel) by Thea von Harbou |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Gottfried Huppertz |

| Cinematography | |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

Ufa (Germany) Parufamet (United States) |

Release date |

|

Running time |

153 minutes (original) 116 minutes (1927 edit) 105–107 minutes (1927 US)[3][4] 128 minutes (1927 UK)[3] 118 minutes (Aug. 1927) 91 minutes (1936) 83 minutes (1984) 124 minutes (2001) 148 minutes (2010) |

| Country | Germany |

| Language |

|

| Budget | 5.3 million Reichsmarks (estimated)[2] |

| Box office | 75,000 Reichsmarks (estimated) |

Metropolis is a 1927 German expressionist science-fiction drama film directed by Fritz Lang. Written by Thea von Harbou, with collaboration from Lang himself,[5][6] it starred Gustav Fröhlich, Alfred Abel, Rudolf Klein-Rogge and Brigitte Helm. Erich Pommer produced it in the Babelsberg Studios for Universum Film A.G. (Ufa). The silent film is regarded as a pioneering work of the science-fiction genre in movies, being among the first feature-length movies of the genre.[7] Filming took place over 17 months in 1925–26 at a cost of over five million Reichsmarks.[8]

Made in Germany during the Weimar Period, Metropolis is set in a futuristic urban dystopia and follows the attempts of Freder, the wealthy son of the city's master, and Maria, a saintly figure to the workers, to overcome the vast gulf separating the classes of their city, and bring the workers together with Joh Fredersen, the master of the city. The film's message is encompassed in the final inter-title: "The Mediator Between the Head and the Hands Must Be the Heart".

Metropolis was met with a mixed reception upon release. Critics found it pictorially beautiful and visually powerful—the film's art direction by Otto Hunte, Erich Kettelhut and Kurt Vollbrecht draws influence from Bauhaus, Cubist and Futurist design,[9] along with touches of the Gothic in the scenes in the catacombs, the cathedral and Rotwang's house[3]—and lauded its complex special effects, but accused its story of naiveté.[10] H. G. Wells described the film as "silly", and The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction calls the film's story "trite" and its politics "ludicrously simplistic".[3] The film's alleged Communist message was also criticized.[11]

The film's extensive running time also came in for criticism, and Metropolis was cut substantially after its German premiere, removing a large portion of Lang's original footage. Numerous attempts have been made to restore the film since the 1970s. Music producer Giorgio Moroder released a truncated version with a soundtrack by rock artists such as Freddie Mercury, Loverboy and Adam Ant in 1984. A new reconstruction of Metropolis was shown at the Berlin Film Festival in 2001. In 2008, a damaged print of Lang's original cut of the film was found in a museum in Argentina. After a long restoration process that required additional materials provided by a print from New Zealand, the film was 95% restored and shown on large screens in Berlin and Frankfurt simultaneously on 12 February 2010.

In 2001, the film was inscribed on UNESCO's Memory of the World Register, the first film thus distinguished.

Plot

In the future, in the city of Metropolis, wealthy industrialists and business magnates and their top employees reign from high-rise towers, while underground-dwelling workers toil to operate the great machines that power the city. Joh Fredersen is the city's master. His son Freder idles away his time at sports and in a pleasure garden, but is interrupted by the arrival of a young woman named Maria, who has brought a group of workers' children to witness the lifestyle of their rich "brothers". Maria and the children are ushered away, but Freder, fascinated, goes to the lower levels to find her. On the machine levels he witnesses the explosion of a huge machine that kills and injures numerous workers. Freder has a hallucination that the machine is Moloch, and the workers are being fed to it. When the hallucination ends and he sees the dead workers being carried away on stretchers, he hurries to tell his father about the accident; Fredersen asks his assistant, Josaphat, why he learned of the explosion from his son, and not from him.

Grot, foreman of the Heart Machine, brings to Fredersen secret maps found on the dead workers. Fredersen again asks Josaphat why he did not learn of the maps from him, and fires him. Freder secretly rebels against Fredersen by deciding to help the workers, after seeing his father's cold indifference towards the harsh conditions they face.

Fredersen takes the maps to the inventor Rotwang to learn their meaning. Rotwang had been in love with a woman named Hel, who left him to marry Fredersen and later died giving birth to Freder. Rotwang shows Fredersen a robot he has built to "resurrect" Hel. The maps show a network of catacombs beneath Metropolis, and the two men go to investigate. They eavesdrop on a gathering of workers, including Freder. Maria addresses them, prophesying the arrival of a mediator who can bring the working and ruling classes together. Freder believes that he could fill the role and declares his love for Maria. Fredersen orders Rotwang to give Maria's likeness to the robot so that it can ruin her reputation among the workers to prevent any rebellion. Fredersen is unaware that Rotwang plans to use the robot to kill Freder and take over Metropolis. Rotwang kidnaps Maria, transfers her likeness to the robot and sends her to Fredersen. Freder finds the two embracing and, believing it is the real Maria, falls into a prolonged delirium. Intercut with his hallucinations, the false Maria unleashes chaos throughout Metropolis, driving men to murder and stirring dissent amongst the workers.

Freder recovers and returns to the catacombs. Finding the false Maria urging the workers to rise up and destroy the machines, Freder accuses her of not being the real Maria. The workers follow the false Maria from their city to the machine rooms, leaving their children behind. They destroy the Heart Machine, which causes the workers' city below to flood. The real Maria, having escaped from Rotwang's house, rescues the children with the help of Freder. Grot berates the celebrating workers for abandoning their children in the flooded city. Believing their children to be dead, the hysterical workers capture the false Maria and burn her at the stake. A horrified Freder watches, not understanding the deception until the fire reveals her to be a robot. Rotwang is delusional, seeing the real Maria as his lost Hel, and he chases her to the roof of the cathedral, pursued by Freder. The two men fight as Fredersen and the workers watch from the street. Rotwang falls to his death. Freder fulfills his role as mediator by linking the hands of Fredersen and Grot to bring them together.

Cast

- Alfred Abel as Joh Fredersen, the master of Metropolis

- Gustav Fröhlich as Freder, Joh Fredersen's son

- Rudolf Klein-Rogge as Rotwang, the inventor

- Fritz Rasp as The Thin Man, Fredersen's spy

- Theodor Loos as Josaphat, Fredersen's assistant and Freder's friend

- Erwin Biswanger as 11811, a worker, also known as Gyorgy

- Heinrich George as Grot, guardian of the Heart Machine

- The Creative Man

- The Machine Man

- Death

- The Seven Deadly Sins

- Brigitte Helm as Maria[Notes 1]

- Heinrich Gotho as Master of Ceremonies in Pleasure Gardens (uncredited)

Cast notes

- Among the uncredited actors are Margarete Lanner, Helen von Münchofen, Olaf Storm, Georg John, Helene Weigel, Fritz Alberti and Curt Siodmak.

- All footage of the character of The Monk, who Freder hears preaching at the cathedral, has been lost, although there is a callback to the scene in the 2010 restoration, when Freder is in bed with a fever and he imagines The Thin Man to be the Monk.

Influences

_-_Google_Art_Project_-_edited.jpg)

Metropolis features a range of elaborate special effects and set designs, ranging from a huge gothic cathedral to a futuristic cityscape. In an interview, Fritz Lang reported that "the film was born from my first sight of the skyscrapers in New York in October 1924". He had visited New York City for the first time and remarked "I looked into the streets—the glaring lights and the tall buildings—and there I conceived Metropolis,"[13] although in actuality Lang and Harbou had been at work on the idea for over a year.[2] Describing his first impressions of the city, Lang said that "the buildings seemed to be a vertical sail, scintillating and very light, a luxurious backdrop, suspended in the dark sky to dazzle, distract and hypnotize".[14] He added "The sight of Neuyork [sic] alone should be enough to turn this beacon of beauty into the center of a film..."[13]

The appearance of the city in Metropolis is strongly informed by the Art Deco movement; however it also incorporates elements from other traditions. Ingeborg Hoesterey described the architecture featured in Metropolis as eclectic, writing how its locales represent both "functionalist modernism [and] art deco" whilst also featuring "the scientist's archaic little house with its high-powered laboratory, the catacombs [and] the Gothic cathedral". The film's use of art deco architecture was highly influential, and has been reported to have contributed to the style's subsequent popularity in Europe and America.[15] The New Babel Tower, for instance, has been inspired by Upper Silesian Tower in Poznań fairgrounds, which was recognized in Germany as a masterpiece of architecture.[16]

Lang's visit to several Hollywood studios in the same 1924 trip also influenced the film in another way: Lang and producer Erich Pommer realized that to compete with the vertical integration of Hollywood, their next film would have to be bigger, broader, and better made then anything they had made before. Despite Ufa's growing debt, Lang announced that Metropolis would be "the costliest and most ambitious picture ever."[2]

The film drew heavily on biblical sources for several of its key set-pieces. During her first talk to the workers, Maria uses the story of the Tower of Babel to highlight the discord between the intellectuals and the workers. Additionally, a delusional Freder imagines the false-Maria as the Whore of Babylon, riding on the back of a many-headed dragon.

The name of the Yoshiwara club alludes to the famous red-light district of Tokyo.[17]

Much of the plot line of Metropolis stems from the First World War and the culture of the Weimar Republic in Germany. Lang explores the themes of industrialization and mass production in his film; two developments that played a large role in the war. Other post-World War I themes that Lang includes in Metropolis include the Weimar view of American modernity, fascism, and communism.[18]

Production

Pre-production

The screenplay of Metropolis was written by Thea von Harbou, a popular writer in Weimar Germany, jointly with Lang, her then-husband.[5][6] The film's plot originated from a novel of the same title written by Harbou for the sole purpose of being made into a film. The novel in turn drew inspiration from H. G. Wells, Mary Shelley and Villiers de l'Isle-Adam's works and other German dramas.[19] The novel featured strongly in the film's marketing campaign, and was serialized in the journal Illustriertes Blatt in the run-up to its release. Harbou and Lang collaborated on the screenplay derived from the novel, and several plot points and thematic elements—including most of the references to magic and occultism present in the novel—were dropped. The screenplay itself went through many re-writes, and at one point featured an ending where Freder would have flown to the stars; this plot element later became the basis for Lang's Woman in the Moon.[20]

The time setting of Metropolis is open to interpretation. The 2010 re-release and reconstruction, which incorporated the original title cards written by Thea von Harbou, do not specify a year. Prior to the reconstruction, Lotte Eisner and Paul M. Jensen placed the events happening around the year 2000.[21][22] Giorgio Moroder's re-scored version included a title card placing the film in 2026, while Paramount's original US release stated that the film takes place in the year 3000.[23] A note in Harbou's novel says that the story does not take place at any particular place or time, in the past or the future.

Filming

Metropolis began principal photography on 22 May 1925 with an initial budget of 1.5 million Reichsmarks.[20] Lang cast two unknowns with little film experience in the lead roles. Gustav Fröhlich (Freder) had worked in vaudeville and was originally employed as an extra on Metropolis before Thea von Harbou recommended him to Lang.[24] Brigitte Helm (Maria) had been given a screen test by Lang after he met her on the set of Die Nibelungen, but would make her feature film debut with Metropolis.[20] In the role of Joh Fredersen, Lang cast Alfred Abel, a noted stage and screen actor whom he had worked with on Dr. Mabuse the Gambler. Lang also cast his frequent collaborator Rudolph Klein-Rogge in the role of Rotwang. This was Klein-Rogge's fourth film with Lang, after Destiny, Dr. Mabuse the Gambler, and Die Nibelungen.

Shooting of the film was a draining experience for the actors involved due to the demands that Lang placed on them. For the scene where the worker's city was flooded, Helm and 500 children from the poorest districts of Berlin had to work for 14 days in a pool of water that Lang intentionally kept at a low temperature.[25] Lang would frequently demand numerous re-takes, and took two days to shoot a simple scene where Freder collapses at Maria's feet; by the time Lang was satisfied with the footage he had shot, actor Gustav Fröhlich found he could barely stand.[25] Other anecdotes involve Lang's insistence on using real fire for the climactic scene where the false Maria is burnt at the stake (which resulted in Helm's dress catching fire), and his ordering extras to throw themselves towards powerful jets of water when filming the flooding of the worker's city.[25][26]

Helm recalled her experiences of shooting the film in a contemporary interview, saying that "the night shots lasted three weeks, and even if they did lead to the greatest dramatic moments—even if we did follow Fritz Lang's directions as though in a trance, enthusiastic and enraptured at the same time—I can't forget the incredible strain that they put us under. The work wasn't easy, and the authenticity in the portrayal ended up testing our nerves now and then. For instance, it wasn't fun at all when Grot drags me by the hair, to have me burned at the stake. Once I even fainted: during the transformation scene, Maria, as the android, is clamped in a kind of wooden armament, and because the shot took so long, I didn't get enough air."[27]

Ufa invited several trade journal representatives and several film critics to see the film's shooting as parts of its promotion campaign.[28]

Shooting lasted 17 months, with 310 shooting days and 60 shooting nights, and was finally completed on 30 October 1926.[26] By the time shooting finished, the film's budget leapt to 5.3 million Reichsmarks, or over three-and-and-half times the original budget.[29][2] Producer Erich Pommer had been fired during production.[2]

Special effects

The effects expert Eugen Schüfftan created pioneering visual effects for Metropolis. Among the effects used are miniatures of the city, a camera on a swing, and most notably, the Schüfftan process,[30] in which mirrors are used to create the illusion that actors are occupying miniature sets. This new technique was seen again just two years later in Alfred Hitchcock's film Blackmail (1929).[31]

The Maschinenmensch – the robot built by Rotwang to resurrect his lost love Hel – was created by sculptor Walter Schulze-Mittendorff. A whole-body plaster cast was taken of actress Brigitte Helm, and the costume was then constructed around it. A chance discovery of a sample of "plastic wood" (a pliable substance designed as wood-filler) allowed Schulze-Mittendorff to build a costume that would both appear metallic and allow a small amount of free movement.[32] Helm sustained cuts and bruises while in character as the robot, as the costume was rigid and uncomfortable.[33]

Music

Original score

The film's original score was composed for a large orchestra by Gottfried Huppertz. Huppertz drew inspiration from Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss, and combined a classical orchestral voice with mild modernist touches to portray the film's massive industrial city of workers.[34] Nestled within the original score were quotations of Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle's "La Marseillaise" and the traditional "Dies Irae," the latter of which was matched to the film's apocalyptic imagery. Huppertz's music played a prominent role during the film's production; oftentimes, the composer played piano on Lang's set in order to inform the actors' performances.

The score was rerecorded for the 2001 DVD release of the film with Berndt Heller conducting the Rundfunksinfonieorchester Saarbrücken. It was the first release of the reasonably reconstructed movie to be accompanied by Huppertz's original score. In 2007, Huppertz's score was also played live by the VCS Radio Symphony, which accompanied the restored version of the film at Brenden Theatres in Vacaville, California.[35] The score was also produced in a salon orchestration, which was performed for the first time in the United States in August 2007 by The Bijou Orchestra under the direction of Leo Najar as part of a German Expressionist film festival in Bay City, Michigan.[36] The same forces also performed the work at the Traverse City Film Festival in Traverse City, Michigan in August 2009.

For the 2010 reconstruction DVD, the score was performed and recorded by the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Frank Strobel. Strobel also conducted the premiere of the reconstructed score at Berlin Friedrichstadtpalast.

Other soundtracks

There have been many other soundtracks created for Metropolis by different artists.

- In 1975, the BBC provided an electronic score composed by William Fitzwater and Hugh Davies.[37]

- In 1984 Giorgio Moroder restored and produced the 80-minute 1984 re-release, which had a pop soundtrack written by Moroder and performed by Moroder, Pat Benatar, Bonnie Tyler, Jon Anderson, Adam Ant, Cycle V, Loverboy, Billy Squier, and Freddie Mercury.

- In 1991 the Club Foot Orchestra created an original score that was performed live with the film. It was also recorded for CD.

- In 1994, Montenegrin experimental rock musician Rambo Amadeus wrote his version of the musical score for Metropolis. At the screening of the film in Belgrade, the score was played by the Belgrade Philharmonic Orchestra.

- In 1998, the material was recorded and released on the album Metropolis B (tour-de-force).[38]

- In 1996 the Degenerate Art Ensemble (then The Young Composers Collective) scored the film for chamber orchestra, performing it in various venues including a free outdoor concert and screening in 1997 in Seattle's Gasworks Park.[39] The soundtrack was subsequently released on Un-Labeled Records.

- In 2000, Jeff Mills created a techno score for Metropolis which was released as an album. He also performed the score live at public screenings of the film.

- In 2004 Abel Korzeniowski created a score for Metropolis played live by a 90-piece orchestra and a choir of 60 voices and two soloists. The first performance took place at the Era Nowe Horyzonty Film Festival in Poland.

- The same year, Ronnie Cramer produced a score and effects soundtrack for Metropolis that won two Aurora awards.[40]

- The New Pollutants (Mister Speed and DJ Tr!p) has performed Metropolis Rescore live for festivals since 2005 and rescored to the 2010 version of the film for premiere at the 2011 Adelaide Film Festival.

- By 2010, the Alloy Orchestra had scored four different versions of the film, including Moroder's, and most recently for the American premiere of the 2010 restoration. A recording of Alloy's full score was commissioned by Kino Lorber, with the intention of it being issued on their remastered Blu-ray and DVD as an alternative soundtrack. However, in the event this was vetoed by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung, as they own the copyright to the restoration and mandate only their own score can accompany it. Alloy's score is available via their website and can be synchronised to the film independently.[41][42]

- In 2012 Dieter Moebius was invited to perform music to the film. For that purpose he produced pre-arranged tracks and samples, combined with live improvisation. Although he died in 2015, the project was later completed, and released in 2016, as Musik fur Metropolis.

- In 2014 the pianist/composer, Dmytro Morykit, created a new live piano score which received a standing ovation to a sell-out audience at Wilton's Music Hall in London.[43]

- Also in 2014, Spanish band Caspervek Trio premiered a new score at "La Galería Jazz" Vigo, with further performances in Budapest, Riga and Groningen. Metavari re-scored Metropolis as a commission from Fort Wayne, Indiana's Cinema Center for Art House Theater Day 2016.[44] The re-score was released worldwide on One Way Static Records for Record Store Day 2017, and distributed in the United States by Light in the Attic Records.[45][46]

- In 2018, flautist Yael Acher "Kat" Modiano composed and performed live a new score for a showing of the 2010 restoration at the United Palace in Upper Manhattan.[47]

_(15418159339).jpg)

Release and reception

Metropolis was distributed by Parufamet, a company formed in December 1925 by the American film studios Paramount Pictures and Metro Goldwyn Mayer to loan $4 million (US) to Ufa.[48] The film had its world premiere at the Ufa-Palast am Zoo in Berlin on 10 January 1927, where the audience, including a critic from the Berliner Morgenpost, reacted to several of the film's most spectacular scenes with "spontaneous applause".[26] However, others have suggested the premiere was met with muted applause interspersed with boos and hisses.[49]

At the time of its German premiere, Metropolis had a length of 4,189 metres, which is approximately 153 minutes at 24 frames per second (fps).[50] Ufa's distribution deal with Paramount and MGM "entitled [them] to make any change [to films produced by Ufa] they found appropriate to ensure profitability". Considering that Metropolis was too long and unwieldy, Parufamet commissioned American playwright Channing Pollock to write a simpler version of the film that could be assembled using the existing material. Pollock shortened the film dramatically, altered its inter-titles and removed all references to the character of Hel, because the name sounded too similar to the English word Hell, thereby removing Rotwang's original motivation for creating his robot. Pollack said about the original film that it was "symbolism run such riot that people who saw it couldn't tell what the picture was about. ... I have given it my meaning." Lang's response to the re-editing of the film was to say "I love films, so I shall never go to America. Their experts have slashed my best film, Metropolis, so cruelly that I dare not see it while I am in England."[2]

In Pollock's cut, the film ran for 3,170 metres, or approximately 116 minutes—although a contemporary review in Variety of a showing in Los Angeles gave the running time as 107 minutes,[4] and another source lists it at 105 minutes.[3] This version of Metropolis premiered in the United States in March 1927, and was released, in a slightly different and longer version (128 minutes)[3] in the United Kingdom around the same time with different title cards.[50][2]

Alfred Hugenberg, a German nationalist businessman, cancelled Ufa's debt to Paramount and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer after taking charge of the company in April 1927, and chose to halt distribution in German cinemas of Metropolis in its original form. Hugenberg had the film cut down to a length of 3,241 metres (about 118 minutes), broadly along the lines of Pollock's edit, removing the film's perceived "inappropriate" communist subtext and religious imagery. Hugenberg's cut of the film was released in German cinemas in August 1927. Later, after demands for more cuts by Nazi censors, Ufa distributed a still shorter version of the film (2,530 metres, 91 minutes) in 1936, and an English version of this cut was archived in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) film library in the 1930s. It was this version which was the basis of all versions of Metropolis until the recent restorations. In 1986, it was re-copied and returned to Germany to be the basis of the 1987 Munich Archive restoration.[50][2]

Original reception

Despite the film's later reputation, some contemporary critics panned it. Critic Mordaunt Hall of The New York Times called it a "technical marvel with feet of clay".[23] The Times went on the next month to publish a lengthy review by H. G. Wells who accused it of "foolishness, cliché, platitude, and muddlement about mechanical progress and progress in general."[51] He faulted Metropolis for its premise that automation created drudgery rather than relieving it, wondered who was buying the machines' output if not the workers, and found parts of the story derivative of Shelley's Frankenstein, Karel Čapek's R.U.R., and his own The Sleeper Awakes.[52] Wells called Metropolis "quite the silliest film." On the other hand, the New York Herald Tribune called it "a weird and fascinating picture."[2]

Writing in The New Yorker, Oliver Claxton called it "unconvincing and overlong", faulting much of the plot as "laid on with a terrible Teutonic heaviness, and an unnecessary amount of philosophizing in the beginning" that made the film "as soulless as the city of its tale." He also described the acting as "uninspired with the exception of Brigitte Helm". Nevertheless, Claxton wrote that "the setting, the use of people and their movement, and various bits of action stand out as extraordinary and make it nearly an obligatory picture."[53] Other critics considered the film a remarkable achievement that surpassed even its high expectations, praising its visual splendour and ambitious production values.[54]

Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels was impressed with the film's message of social justice. In a 1928 speech he declared that "the political bourgeoisie is about to leave the stage of history. In its place advance the oppressed producers of the head and hand, the forces of Labor, to begin their historical mission".[55] Shortly after the Nazis came to power, Goebbels told Lang that, on the basis of their seeing Metropolis together years before, Hitler had said then that he wanted Lang to make Nazi films.[56]

Internationally, German cultural critic Siegfried Kracauer later wrote of Metropolis that "The Americans relished its technical excellence; the English remained aloof; the French were stirred by a film which seemed to them a blend of [composer] Wagner and [armaments manufacturer] Krupp, and on the whole an alarming sign of Germany's vitality."[57]

Fritz Lang himself later expressed dissatisfaction with the film. In an interview with Peter Bogdanovich in Who The Devil Made It: Conversations with Legendary Film Directors, published in 1998, he expressed his reservations:

The main thesis was Mrs. Von Harbou's, but I am at least 50 percent responsible because I did it. I was not so politically minded in those days as I am now. You cannot make a social-conscious picture in which you say that the intermediary between the hand and the brain is the heart. I mean, that's a fairy tale—definitely. But I was very interested in machines. Anyway, I didn't like the picture—thought it was silly and stupid—then, when I saw the astronauts: what else are they but part of a machine? It's very hard to talk about pictures—should I say now that I like Metropolis because something I have seen in my imagination comes true, when I detested it after it was finished?

In his profile of Lang, which introduced the interview, Bogdanovich suggested that Lang's distaste for his own film also stemmed from the Nazi Party's fascination with the film. Von Harbou became a member of the Party in 1933. She and Lang divorced the following year.[58] Lang would later move to the United States to escape the Nazis, while Harbou stayed in Germany and continued to write state-approved films.

Later acclaim

Roger Ebert noted that "Metropolis is one of the great achievements of the silent era, a work so audacious in its vision and so angry in its message that it is, if anything, more powerful today than when it was made."[59] Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide said in 2005 that the film was "Heavy going at times but startling set design and special effects command attention throughout."[60]

The film has a 99% rating at Rotten Tomatoes, based on 118 reviews,[61] and was ranked No. 12 in Empire magazine's "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema" in 2010.[62] It was ranked number 2 in a list of the 100 greatest films of the Silent Era.[63] The 2002 version was awarded the New York Film Critics Circle Awards "Special Award" for the restoration. In 2012, in correspondence with the Sight & Sound Poll, the British Film Institute called Metropolis the 35th-greatest film of all time.[64]

Lane Roth in Film Quarterly called it a "seminal film" because of its concerns with "profound impact technological progress has on man's social and spiritual progress" and concluded that "ascendancy of artifact over nature is depicted not as liberating man, but as subjugating and corrupting him".[65]

Exploring the dramatic production background and historical importance of the film's complex political context in The American Conservative, Cristobal Catalan suggests "Metropolis is a passionate call, and equally a passionate caution, for social change".[66] Peter Bradshaw noted that The Maschinenmensch Robot based on Maria is "a brilliant eroticisation and fetishisation of modern technology."[67]

Restorations

The original premiere cut of Metropolis has been lost, and for decades the film could be seen only in heavily truncated edits that lacked nearly a quarter of the original length. However, over the years, various elements of footage have been rediscovered.[68] This was the case even though cinematographer Karl Freund followed the usual practice of the time of securing three printable takes of each shot, to create three camera negatives which could be edited for striking prints. Two of these negatives were destroyed when the film was re-edited, by Paramount for the US market, and for the UK market. Ufa itself cut the third negative for the August 1927 release.[2]

East German version (1972)

Between 1968 and 1972, the Staatliches Filmarchiv der DDR, with the help of film archives from around the world, put together a version of Metropolis which restored some scenes and footage, but the effort was hobbled by a lack of a guide, such as an original script, to determine what, exactly, was in the original version.[2]

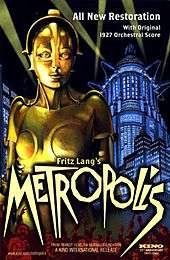

Giorgio Moroder Presents Metropolis (1984)

In 1984, a new restoration and edit of the film, running 83 minutes, was made by music producer Giorgio Moroder, who outbid David Bowie for the rights.[2] Moroder's version, which was made in consultation with the Munich Film Archive and their archivist, Enno Patalas,[2] was tinted, featured additional special effects, replaced intertitles of character dialogue with subtitles and incorporated a soundtrack featuring songs by popular recording artists instead of a traditional score. It was the first serious attempt made at restoring Metropolis to Lang's original vision, and until the restorations in 2001 and 2010, it was the most complete version of the film commercially available; the shorter run time was due to the extensive use of subtitles and a faster frame rate than the original.

Moroder's version of Metropolis generally received poor reviews, to which Moroder responded, telling The New York Times "I didn't touch the original because there is no original."[2] The film was nominated for two Raspberry Awards, Worst Original Song for "Love Kills" and Worst Musical Score for Moroder.[69]

In August 2011, after years of the Moroder version being unavailable on video in any format due to music licensing problems, it was announced that Kino International had managed to resolve the situation, and the film was to be released on Blu-ray and DVD in November. In addition, the film would have a limited theatrical re-release.[70]

Munich Archive version (1987)

The moderate commercial success of the Moroder version inspired Enno Patalas, the archivist of the Munich Film Archive, to make an exhaustive attempt to restore the movie in 1986. Starting from the version in the Museum of Modern Art collection,[71] this version took advantage of new acquisitions and newly discovered German censorship records of the original inter-titles, as well as the musical score and other materials from the estate of composer Gottfried Huppertz. The Munich restoration also utilized newly rediscovered still photographs to represent scenes that were still missing from the film. The Munich version was 9,840 feet, or 109 minutes long.[2]

Restored Authorized Edition (2001)

Beginning in 1998, Martin Körber, a film preservationist, commissioned by Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung, began an effort to expand on the Munich version of Metropolis to create a "definitive" restoration of the film. Previously unknown sections of the film were discovered in film museums and archives around the world, including a nitrate original camera negative from the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv, as well as nitrate prints from the George Eastman House, the British Film Institute and the Fondazione Cineteca Italiana. These original film elements, digitally "cleaned" and repaired to remove defects, were used to assemble the film. Newly written inter-titles were used to explain missing scenes.[2]

The 2001 restoration featured a new recording of the original score by Gottfried Huppertz, performed by a 65-piece orchestra. The running time was 124 minutes. The restoration premiered on 15 February 2001 at the Berlin Film Festival, but with a new score by Bernd Schultheis, performed live by the Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin.[2]

In 2002, in conjunction with Kino International, Metropolis's current copyright holder, the F. W. Murnau Foundation released the 2001 restoration, complete with Huppertz' original score, under the title the Restored Authorized Edition.

The Complete Metropolis (2010)

On 1 July 2008, film experts in Berlin announced that a 16 mm reduction negative of the original cut had been discovered in the archives of the Museo del Cine in Buenos Aires, Argentina.[72][73] The negative was a safety reduction made in the 1960s or '70s from a 35 mm positive of Lang's original version, which an Argentinian film distributor had obtained in advance of arranging theatrical engagements in South America. The safety reduction was intended to safeguard the contents in case the original's flammable nitrate film stock was destroyed.[2] The negative was passed to a private collector, an art foundation and finally the Museo del Cine.

The print was investigated by the Argentinian film collector/historian and TV presenter Fernando Martín Peña, along with Paula Felix-Didier, the head of the museum, after Peña heard an anecdote from a cinema club manager expressing surprise at the length of a print of Metropolis he had viewed.[74][2] The print was indeed Lang's full original, with about 25 minutes of footage, around one-fifth of the film, that had not been seen since 1927.[2]

Under the auspices of the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung, Berlin's Deutsche Kinemathek and Museo del Cine, a group of experts, including Anke Wilkening, Martin Körber, and Frank Strobel began combining the newly discovered footage with the existing footage from the 2001 restoration. One of their major problems was that the Argentinian footage was in very bad condition, with many scratches, streaks, and changes in brightness. Some of this they were able to overcome with digital technology, something that would not have been possible even in 2001. The reconstruction of the film with the new footage was once again aided by the original music score, including Huppertz' handwritten notes, which acted as the key resource in determining where the new footage went. Since the Argentinian print was a complete version of the original, some scenes from the 2001 restoration were put in different places than they had been in, and the tempo of the original editing was restored.[2]

In 2005, Australian historian and politician Michael Organ had examined a print of the film in the National Film Archive of New Zealand. Organ discovered that the print contained scenes missing from other copies of the film. After hearing of the discovery of the Argentine print of the film and the restoration project, Organ contacted the German restorers; the New Zealand print contained 11 missing scenes and featured some brief pieces of footage that were used to restore damaged sections of the Argentine print. It is believed that the New Zealand and Argentine prints were all sourced from the same master. The newly discovered footage was used in the restoration project.[75] The Argentine print was in poor condition and required considerable restoration before it was re-premiered in February 2010. Two short sequences, depicting a monk preaching and a fight between Rotwang and Fredersen, were damaged beyond repair. Title cards describing the action were inserted by the restorers to compensate. The Argentine print revealed new scenes that enriched the film's narrative complexity. The characters of Josaphat, the Thin Man, and 11811 appear throughout the film and the character Hel is reintroduced.[76]

The new restoration was premiered on 12 February 2010 simultaneously in Berlin at the Friedrichstadt-Palast and on an outdoor screen at the Brandenburg Gate, as well as at the Alte Oper in Frankfurt am Main. The Brandenburg Gate showing was also telecast live by the Arte network. The North American premiere took place at the 2010 TCM Classic Film Festival in Mann's Chinese Theatre in Los Angeles on 25 April 2010.[2] The new restoration was released on DVD and Blu-Ray by Kino Video in 2010 under the title The Complete Metropolis.

Copyright

The American copyright for Metropolis lapsed in 1953, which led to a proliferation of versions being released on video. Along with other foreign-made works, the film's U.S. copyright was restored in 1996 by the Uruguay Round Agreements Act,[77] but the constitutionality of this copyright extension was challenged in Golan v. Gonzales and as Golan v. Holder, it was ruled that "In the United States, that body of law includes the bedrock principle that works in the public domain remain in the public domain. Removing works from the public domain violated Plaintiffs' vested First Amendment interests."[78] This only applied to the rights of so-called reliance parties, i.e. parties who had relied on the public domain status of restored works. The case was overturned on appeal to the Tenth Circuit,[78] and that decision was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court on 18 January 2012. This had the effect of restoring the copyright in the work as of 1 January 1996.

Though it will remain copyrighted in Germany and the rest of the European Union until the end of 2046, seventy years after Fritz Lang's death,[Notes 2] under current U.S. copyright law it will be copyrighted there only through 31 December 2022 due to the rule of the shorter term as implemented in the Uruguay Round Agreements Act; the U.S. copyright limit for films of its age is 95 years from publication per the Copyright Term Extension Act.

Adaptations

- Several adaptations have been made of the original Metropolis, including a 1989 musical theatre adaptation, Metropolis, which was performed on the West End in London and in Chicago. The play's music was written by Joe Brooks and the lyrics by Dusty Hughes[79]

- In December 2007, it was announced that producer Thomas Schühly (Alexander, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen) had obtained the remake rights to Metropolis.[80]

- In December 2016, it was announced that Sam Esmail (Mr. Robot) would adapt the film into a mini-series.[81] This has not come about.

- The Metropolis manga, sometimes referred to as Osamu Tezuka's Metropolis or Robotic Angel, has some parallels to the film. However, writer Osamu Tezuka stated that he had only seen a single still image of the movie in a magazine at the time of creating his manga. The manga has been adapted into a feature-length anime, released in 2001.

In popular culture

- Madonna's 1989 music video "Express Yourself" pays homage to the film and Fritz Lang.[82]

- The Norwegian gothic rock band Seigmen released an album called Metropolis, featuring pictures of the movie's architecture as cover art.

- Janelle Monáe based both her concept albums on the original film including her EP, Metropolis: Suite I (The Chase) released mid-2007 and The ArchAndroid released in 2009. The latter also included an homage to Metropolis on the album cover, with the film version of the Tower of Babel among the remainder of the city. The albums follow the adventures of Monáe's alter-ego and robot, Cindi Mayweather, as a messianic figure to the android community of Metropolis.[83][84]

- Videos for songs by pop singer-songwriter Lady Gaga have made a series of references to Lang's film. Visual allusions to the film are noted most predominantly in the music videos for "Alejandro", "Born This Way", and "Applause".[85]

- The Brazilian metal band Sepultura named their 2013 album The Mediator Between Head and Hands Must Be the Heart after a quote from the film.[86]

- The 2014 music video "Digital Witness" by St. Vincent in collaboration with Chino Moya presents "a surreal, pastel-hued future" in which lead singer Annie Clark is a stand-in for Maria.[87]

See also

References

Informational notes

- ↑ In the film's opening credits, several characters appear in the cast list without the names of the actors who play them: The Creative Man, The Machine Man, Death, and The Seven Deadly Sins. These roles sometimes are incorrectly attributed to Brigitte Helm, since they appear just above her credit line. Brigitte Helm actually did perform the role of The Machine Man, as shown by production stills which show her inside the robot costume, such as at https://capitalpictures.photoshelter.com/image/I0000Cy4itqVZqTg.

- ↑ § 65 co-authors, cinematographic works, musical composition with words

(2) In the case of film works and works similar to cinematographic works, copyright expires seventy years after the death of the last survivor of the following persons: the principal director, author of the screenplay, author of the dialogue, the composer of music for the cinematographic music.

The people considered under this German law are director Fritz Lang (died 1976), writer Thea von Harbou (died 1954), and possibly score composer Gottfried Huppertz (died 1937).

Citations

- ↑ Kreimeier 1999, p. 156.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Bennett, Bruce (2010) "The Complete Metropolis: Film Notes" Kino DVD K-659

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Brosnan, Joan and Nichols, Peter "Metropolis" in Clute, John and Nichols, Peter (eds.) (1995) The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction New York: St.Martin's Griffin. p.805. ISBN 0-312-13486-X

- 1 2 Staff (1927) "Metropolis" (review) Variety

- 1 2 Magid 2006, p. 129.

- 1 2 Grant 2003, p. 14.

- ↑ "Metropolis (1927)" Science Fiction Film History. Retrieved 15 May 2013. Quote: "Although the first science fiction film is generally agreed to be Georges Méliès' A Trip To The Moon (1902), Metropolis (1926) is the first feature length outing of the genre."

- ↑ Hahn, Ronald M. and Jansen, Volker (1998) Die 100 besten Kultfilme Munich: Heyne Filmbibliothek. p.396. ISBN 3-453-86073-X(German)

- ↑ McGilligan 1997, p. 112.

- ↑ McGilligan 1997, p. 130.

- ↑ McGilligan 1997, p. 131.

- ↑ Bukatman 1997, pp. 62–3.

- 1 2 Minden & Bachmann 2002, p. 4.

- ↑ Grant 2003, p. 69.

- ↑ Russell 2007, p. 111.

- ↑ Upper Silesian Tower, Poznań on 1911 postcard

- ↑ White 1995, p. 348.

- ↑ Kaes, Anton (2009). Shell Shock Cinema: Weimar Culture and the Wounds of War. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-03136-1.

- ↑ Minden & Bachmann 2002, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 Minden & Bachmann 2002, p. 12.

- ↑ Eisner 1986, p. 83.

- ↑ Jensen 1969, p. 59.

- 1 2 Hall, Mordaunt (7 March 1927). "Movie review Metropolis (1927) A Technical Marvel". The New York Times.

- ↑ McGilligan 1997, p. 113.

- 1 2 3 Minden & Bachmann 2002, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 Miller, Frank. "Metropolis (1927)". TCM.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ Helm, Brigitte (15 May 2010). French, Lawrence, ed. "The Making of Metropolis: Actress Brigitte Helm – The Maria of the Underworld, of Yoshiwara, and I". Cinefantastique. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ Minden & Bachmann 2002, p. 24.

- ↑ Minden & Bachmann 2002, p. 19.

- ↑ Mok 1930, pp. 22–24, 143–145.

- ↑ Cock, Matthew (25 August 2011). "Hitchcock's Blackmail and the British Museum: film, technology and magic". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ Schulze-Mittendorff, Bertina. "The Metropolis Robot – Its Creation". Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ McGilligan 1997, pp. 115-6.

- ↑ Minden & Bachmann 2002, p. 125.

- ↑ "VCS to play live film score at screening review". The Reporter. 25 July 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ "State Theater August Line Up in Downtown Bay City". State Theater of Bay City. Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ↑ "Hugh Davies – Electronic Music Studios in Britain: Goldsmiths, University of London". gold.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- ↑ "Rambo Amadeus & Miroslav Savić – Metropolis B". discogs.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ "Metropolis - revival of our 1997 orchestral score". degenerateartensemble.com/. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ "Ronnie Cramer". cramer.org/. Archived from the original on 15 August 2000. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ Alloy Orchestra: Metropolis – MP3 CD, 2010 Complete Score

- ↑ The Alloy Orchestra's Ken Winokur on the vetoing of their Metropolis score, September 9, 2010

- ↑ "Metropolis: live performance in Leamington of brand new music score". leamingtomcourier.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ "Scoring The Silence". www.fortwaynereader.com. Retrieved 2017-05-02.

- ↑ "One Way Static". One Way Static. Retrieved 2017-05-02.

- ↑ "Metavari - Metropolis (An Original Re-Score by Metavari) | Light In The Attic Records". Light In The Attic Records. Retrieved 2017-05-02.

- ↑ Staff (February 20, 2018) "United Palace to Screen Metropolis With Live Score" Broadway World

- ↑ "100 Jahre Ufa Traum ab!" (in German). Berliner Kurier. 17 September 2017.

- ↑ Minden & Bachmann 2002, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 Fernando Martín, Peña (2010). "Metropolis Found". fipresci. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ McGilligan 1997, pp. 130a.

- ↑ "H.G. Wells on "Metropolis" (1927)". erkelzaar.tsudao.com. Archived from the original on 22 March 2008. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ Claxton, Oliver (12 March 1927). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. New York: F-R Publishing Company: 80–81.

- ↑ Kaplan 1981, p. 146.

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1997, p. 25.

- ↑ Kracauer 1947, p. 164.

- ↑ Kracauer 1947, p. 150.

- ↑ McGilligan 1997, p. 181.

- ↑ Ebert 1985, p. 209.

- ↑ Maltin, Leonard ed. (2005) Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide 2005 New York: Plume. p.914 ISBN 0-452-28592-5

- ↑ "Metropolis". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema". empireonline.com. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ "The Top 100 Silent Era Films". silentera.com. Archived from the original on 23 August 2000. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ "The Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time". Sight & Sound. British Film Institute. September 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ↑ Roth 1978, p. 342.

- ↑ "Metropolis at 90". American Conservative. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ↑ Bradshaw, Peter (9 September 2010). "Metropolis". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ↑ "About Metropolis". Archived from the original on 9 August 2007. Retrieved 25 January 2007.

- ↑ Wilson 2005, p. 286.

- ↑ Kit, Borys (24 August 2011). "Rock Version of Silent Film Classic 'Metropolis' to Hit Theatres This Fall". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 30 January 2014.

- ↑ Codelli, Lorenzo (November 1984) "Entretien avec Enno Patalas, conservateur de la cinémathèque de Munich, sur Metropolis et quelques autres films de Fritz Lang" in Positif n.285, pp.15 sqq.

- ↑ "Metropolis: All New Restoration". Kino Lorber. Archived from the original on 5 October 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ↑ "Film: Long lost scenes from Fritz Lang's Metropolis found in Argentina". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ↑ "Fritz Lang's Metropolis: Key scenes rediscovered". Die Zeit. 2 July 2008. Archived from the original on 24 June 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- ↑ Pennells, Steve (14 February 2010). "Cinema's Holy Grail". Sunday Star Times. New Zealand. p. C5.

- ↑ "A Tale of Two Cities: Metropolis Restored". Film Comment. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ↑ "Golan v. Ashcroft: Compaint". cyber.law.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 19 April 2003. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- 1 2 "Public Domain Victory in Golan v. Holder". digital-scholarship.org. Archived from the original on 28 September 2010. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ↑ "`Metropolis' Adaptation Opens Renovated Olympic Theatre". articles.chicagotribune.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ Meza, Ed (9 December 2007). "'Metropolis' finds new life". Variety. Archived from the original on 17 February 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ Littleton, Cynthia (16 December 2016). "'Mr. Robot' Creator Sam Esmail Sets 'Metropolis,' 'Homecoming' Development Projects". Variety. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ↑ Michael 2004, p. 89.

- ↑ "Metropolis, Suite 1: The Chase". All Music. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ Kot, Greg. "Turn It Up: Janelle Monae, the interview: 'I identify with androids'". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ↑ "Every Cultural Reference You Probably Didn't Catch In Lady Gaga's New Video". BuzzFeed. Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ Navas, Judy Cantor (24 September 2013). "Sepultura Talks 'Tricky' 'Mediator' Album, Tour Dates Announced". Billboard. Archived from the original on 30 August 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ↑ Locker, Melissa (5 February 2014). "Music Video of the Week: St Vincent, 'Digital Witness'". Time. Archived from the original on 6 February 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

Bibliography

- Bukatman, Scott (1997). Blade Runner. London: BFI modern classics, British Film Institute. ISBN 0-85170-623-1.

- Ebert, Roger (1985). Roger Ebert's Movie Home Companion: 400 Films on Cassette, 1980-85. Andrews, McMeel & Parker. ISBN 978-0-8362-6209-4.

- Eisner, Lotte (1986). Fritz Lang. Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80271-3.

- Grant, Barry Keith, ed. (2003). Fritz Lang: Interviews. Conversations with Filmmakers Series. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781578065776.

- Hoesterey, Ingeborg (2001). Pastiche: cultural memory in art, film, literature. Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21445-4.

- Jensen, Paul M. (1969). The cinema of Fritz Lang. New York: A. S. Barnes. ISBN 0302020020.

- Kaplan, E. Ann (1981). Fritz Lang: A Guide to References and Resources. Boston: G.K. Hall & Co. ISBN 978-0-8161-8035-6.

- Kreimeier, Klaus (1999). The Ufa Story: A History of Germany's Greatest Film Company, 1918–1945. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22069-2.

- Kracauer, Siegfried (1947). From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of German Film. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02505-3.

- Magid, Annette M. (Summer 2006). "Better than the Book: Fritz Lang's Interpretation of Thea von Harbou's Metropolis" (PDF). Spaces of Utopia. No. 2. Universidade do Porto. pp. 129–149. ISSN 1646-4729. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- McGilligan, Patrick (1997). Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-19454-3.

- Michael, Mick St. (2004). Madonna 'Talking': Madonna in Her Own Words. Omnibus Press. ISBN 1-84449-418-7.

- Minden, Michael; Bachmann, Holger (2002). Fritz Lang's Metropolis: Cinematic Visions of Technology and Fear. New York: Camden House. ISBN 978-1-57113-146-1.

- Mok, Michel (May 1930). "New Ideas Sweep Movie Studios". Popular Science. Popular Science Publishing. 116 (5). ISSN 0161-7370.

- Roth, Lane (1978). ""Metropolis", The Lights Fantastic: Semiotic Analysis of Lighting Codes in Relation to Character and Theme". Film Quarterly. 6 (4): 342. JSTOR 43795693.

- Russell, Tim (2007). Fill 'er Up!: The Great American Gas Station. Minneapolis: Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-2871-2.

- Schoenbaum, David (1997). Hitler's Social Revolution: Class and Status in Nazi Germany 1933–1939. London: WW Norton and Company. ISBN 0-393-31554-1.

- White, Susan M. (1995). The Cinema of Max Ophuls: Magisterial Vision and the Figure of Woman. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10113-4.

- Wilson, John (2005). The Official Razzie Movie Guide: Enjoying the Best of Hollywood's Worst. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 0-446-69334-0.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Metropolis (1927 film) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Metropolis (film). |

- The official Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung site for the complete restoration

- The official Eureka/Masters of Cinema (UK) site for the complete restoration

- The official Kino (US) site for the complete restoration

- Metropolis on IMDb

- Metropolis at the TCM Movie Database

- Metropolis at AllMovie

- Metropolis at Rotten Tomatoes

- Metropolis at Metacritic

- Metropolis film review by H. G. Wells

- Metropolis Archive (2011) Michael Organ

- Metropolis Archive movie stills and literature

- Metropolis British premiere original programme (1927)