Vangelis

| Vangelis | |

|---|---|

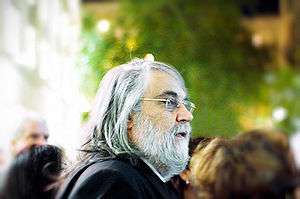

Vangelis at the premiere of El Greco (2007) | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Evángelos Odysséas Papathanassíou |

| Born |

29 March 1943 Agria, Italian-occupied Greece |

| Origin | Volos, Greece |

| Genres | Electronic, progressive rock, classical, ambient |

| Occupation(s) | Composer, musician, record producer, arranger |

| Instruments | Piano, synthesizer, keyboards, Hammond organ, drums, percussion |

| Labels | Universal, RCA, Atlantic, Sony, Warner Bros., Polydor, Deutsche Grammophon |

| Associated acts | Aphrodite's Child, Jon & Vangelis, Demis Roussos |

Evángelos Odysséas Papathanassíou[lower-alpha 1] (born 29 March 1943), best known professionally as Vangelis (/væŋˈɡɛlɪs/; Greek: Βαγγέλης [vaɲˈɟelis]), is a Greek composer of electronic, progressive, ambient, jazz, and orchestral music.[1] He is best known for his Academy Award–winning score for the film Chariots of Fire, composing scores for the films Blade Runner, Missing, Antarctica, 1492: Conquest of Paradise, and Alexander, and the use of his music in the PBS documentary Cosmos: A Personal Voyage by Carl Sagan.[1]

Vangelis began his professional musical career working with several popular bands of the 1960s such as the Forminx and Aphrodite's Child, with the latter's album 666 going on to be recognized as a psychedelic classic.[1][2] Throughout the 1970s, Vangelis composed music scores for several animal documentaries, including L'Apocalypse des Animaux, La Fête sauvage and Opéra sauvage; the success of these scores brought him into the film scoring mainstream. In the early 1980s, Vangelis formed a musical partnership with Jon Anderson, the lead singer of progressive rock band Yes, and the duo went on to release several albums together as Jon & Vangelis.

In 1981, he composed the score for the Oscar-winning film Chariots of Fire, for which he won an Academy Award for Best Original Score. The soundtrack's single, the film's "Titles" theme, also reached the top of the American Billboard Hot 100 chart and was used as the background music at the London 2012 Olympics winners' medal presentation ceremonies.[1] Vangelis also received acclaim for his synthesizer-based soundtrack for the 1982 film Blade Runner.

Having had a career in music spanning over 50 years and having composed and performed more than 50 albums, Vangelis is considered to be one of the most important figures in the history of electronic music.[3][4][5]

Biography

Formative years

Vangelis was born 29 March 1943, in Agria, near Volos, Greece. Largely a self-taught musician, he reportedly began composing at the age of three.[1] His earliest memories include playing piano, percussion, and music of his own device.[6] Throughout his career, Vangelis has not had substantial knowledge of reading or writing musical notation. He rebuffed his parents' attempts to supplement his experimentation with formal training.[7] Vangelis has called himself fortunate to not attend music school, which he considers a creative impediment.[3] He studied painting, an art he still practices, at the Athens School of Fine Arts. Vangelis said in an interview with Life, when asked about his lack of ability to read music:

When the teachers asked me to play something, I would pretend that I was reading it and play from memory. I didn't fool them, but I didn't care.[8]

Work in Aphrodite's Child and other bands

When Vangelis was twelve years old he became interested in jazz music, and with the social movement to rock and roll.[9] At fifteen, he started to form school bands, not to cover other musicians but to have fun.[10] In the early 1960s Vangelis was one of the founders of pop rock group The Forminx (or the Formynx), which became popular in Greece.[11] Based in Athens, the five-piece band played a mixture of cover versions and their own material, the latter written mostly by Vangelis with lyrics by DJ and record producer Nico Mastorakis, and sung in English. The Forminx released nine singles and a Christmas EP before disbanding in 1966 at the peak of their success.[11] A film being made about them at the time, directed by Theo Angelopoulos, was never completed and the songs composed for the movie were never released. Vangelis spent the next two years mostly studio-bound, writing and producing for other Greek artists.[12]

Around the time of the student riots in 1968,[3] Vangelis founded the progressive rock band Aphrodite's Child together with Demis Roussos, Loukas Sideras, and Anargyros "Silver" Koulouris. After an unsuccessful attempt to enter the UK, they found a home in Paris where they recorded their first single, a hit across much of Europe called "Rain and Tears". Other singles followed, along with two albums, which, in total, sold over 20 million copies. The record sales led the record company to request a third album, and Vangelis went on to conceive the double-album 666, based on Revelation, the last book in the Bible. It is sometimes considered one of the best progressive rock albums.[3] Irene Papas provided the vocals for the track "Infinity". Tensions between members during the recording of 666 eventually caused the split of the band in 1971, prior to the album's release the following year. Despite the split, Vangelis subsequently produced several albums and singles for Demis Roussos, who, in turn, contributed vocals to the Blade Runner soundtrack.[12][13][14] He often recalls that the music industry "was under the impression that in order to be alive and to be able to create what I had in mind I had to become successful. I realised that success and pure creativity are not very compatible... Instead of being able to move forward freely and do what you really wish, you find yourself stuck and obliged to repeat yourself and your previous success".[15]

Early solo works

While still in Aphrodite's Child, Vangelis had already been involved in other projects. In the 1960s he scored music for three Greek films; My Brother, the Traffic Policeman (1963) directed by Filippos Fylaktos, 5,000 Lies (1966) by Giorgos Konstantinou and To Prosopo tis Medousas (1967) by Nikos Koundouros. In 1970 he composed the score for Sex-Power directed by Henry Chapier, followed by Salut, Jerusalem in 1972 and Amore in 1974.[1]

In 1971, some jam sessions with a group of musicians in London resulted in two albums' worth of material, unofficially released without Vangelis' permission in 1978, titled Hypothesis and The Dragon. Vangelis succeeded in taking legal action to have them withdrawn.[16] A more successful project was his scoring of wildlife documentary films in the early 1970s made by French filmmaker Frédéric Rossif. The first soundtrack, L'Apocalypse des animaux, was released in 1973.[17] In 1972, the student riots of 1968 provided the inspiration for an album titled Fais que ton rêve soit plus long que la nuit (Make Your Dream Last Longer Than the Night), comprising musical passages mixed with news snippets and protest songs; some lyrics were based on graffiti daubed on walls during the riots.[17][18] He also provided music for the 1973 Henry Chapier film Amore.

In 1973 Vangelis' solo career began in earnest. His second solo album was Earth. It was a percussive-orientated album with Byzantine undertones.[17] It featured a group of musicians including ex-Aphrodite's Child guitarist Silver Koulouris and also vocalist and songwriter Robert Fitoussi (better known as F.R. David of "Words" fame).[19] This line-up, later briefly performing under the name "Odyssey", released a single in 1974 titled "Who", but that was Vangelis' last involvement with them. Later in 1974, Vangelis was widely tipped to join another prog-rock band, Yes, following the departure of Rick Wakeman. After a couple of weeks of rehearsals Vangelis wavered on the option of joining Yes,[16][20] and the band hired Swiss keyboard player Patrick Moraz instead. Vangelis did, however, become friends with Yes' lead vocalist Jon Anderson and later worked with him on several occasions, including as the duo Jon & Vangelis.[21]

Solo career breakthrough

After moving to London in 1975, Vangelis signed with RCA Records, set up his own studio, Nemo Studios,[22] and began recording a string of electronic albums.[1] The first of these, Heaven and Hell, was released in 1975 and was premiered at The Royal Albert Hall.[23] This was followed by Albedo 0.39 (1976), Spiral (1977), Beaubourg (1978) and China (1979). Each of the albums had particular thematic inspiration; Heaven and Hell the homonymous mythological places, Albedo 0.39 the universe, Spiral the Tao philosophy,[23] Beaubourg a visit to the Centre Georges Pompidou while China took inspiration from Chinese cultural and musical traditions.[24]

Vangelis provided the score for Do You Hear the Dogs Barking? directed by François Reichenbach. This was released in 1975 and re-released two years later.[24]

In 1976 Vangelis released his second soundtrack for a Rossif animal documentary, La Fête sauvage, which combined African rhythms with Western music.[24] This was followed in 1979 by a third soundtrack for Rossif, Opéra sauvage. Almost as well known as L'Apocalypse des animaux, this soundtrack brought him to the attention of some of the world's top filmmakers. The music itself would be re-used in other films, most notably the track "L'Enfant" in The Year of Living Dangerously (1982) by Peter Weir; the melody of the same track (in marching band format) can also be heard at the beginning of the 1924 Summer Olympics opening ceremonies scene in the film Chariots of Fire while the track "Hymne" was used in Barilla pasta commercials in Italy and Ernest & Julio Gallo wine ads in the US.[25][26] Rossif and Vangelis again collaborated for Sauvage et Beau (1984)[27] and De Nuremberg à Nuremberg (1989).[28]

In 1979 Vangelis released the album Odes, which included Greek folk songs performed by Vangelis and actress Irene Papas. It was an instant success in Greece[24] and was followed by a second collaboration album, Rapsodies, in 1986.[26]

The 1980s saw the release of five solo albums; the experimental and satirical See You Later (which included "Memories of Green", later featured in the 1982 film Blade Runner) came in 1980;[29] Soil Festivities (1984) was thematically inspired by the interaction between nature and its microscopic living creatures;[27] Invisible Connections (1985) took inspiration from the world of elementary particles invisible to the naked eye;[27] Mask (1985) was inspired by the theme of the mask, an obsolete artefact which was used in ancient times for concealment or amusement;[27] and Direct (1988). The latter was the first album to be recorded in the post-Nemo Studios era.[28]

There were another five solo albums in the 1990s; The City (1990) was recorded during a stay in Rome in 1989, and reflected a day of bustling city life, from dawn until dusk;[28] Voices (1995) featured sensual songs filled with nocturnal orchestrations; Oceanic (1996) thematically explored the mystery of underwater worlds and sea sailing;[30] and two classical albums about El Greco - Foros Timis Ston Greco (1995), which had a limited release, and El Greco (1998), which was an expansion of the former.[31]

Notable film work

Chariots of Fire

In 1981, Vangelis wrote the score for the film Chariots of Fire, set at the 1924 Summer Olympics. The choice of music was unorthodox as most period films featured traditional orchestral scores, whereas Vangelis' music was modern and synthesizer-heavy. The movie won the Academy Award for Best Picture and Vangelis won the Academy Award for Best Original Music Score. The opening theme of the film was released as a single in 1982, topping the American Billboard chart for one week after climbing steadily for five months.[32] It was used at the 1984 Winter Olympics.[3] Vangelis commented that the "main inspiration was the story itself. The rest I did instinctively, without thinking about anything else, other than to express my feelings with the technological means available to me at the time".[15]

Blade Runner

In 1982, Vangelis collaborated with director Ridley Scott to write the score for the science fiction film Blade Runner.[33] Critics have written that in capturing the isolation and melancholy of Harrison Ford's character, Rick Deckard, the Vangelis score is as much a part of the dystopian environment as the decaying buildings and ever-present rain.[34] The score was nominated for BAFTA and Golden Globe awards.

A disagreement led to Vangelis withholding permission for his performance of the music from Blade Runner to be released, and the studio instead hired a group of musicians dubbed "The New American Orchestra" to record the official LP released at the time. It took 12 years before the disagreement was resolved and Vangelis' own work was released in the United States in 1994. The soundtrack was considered incomplete, as the film contained some non-Vangelis tracks which were not included.[35] Over the years a number of bootleg recordings of the Blade Runner soundtrack from unknown sources have been released, mostly targeted to collectors as "private releases", that contain most of the music cues (including the Ladd Company logo theme).[36] An official three-disc box set was released in late 2007 to commemorate the film's 25th anniversary: it contained the original 1994 album, a second disc containing some of the missing music cues and a third disc of new Vangelis material inspired by Blade Runner. The 2007 release still lacks some incidental music, most notably the background music from the Taffey Lewis bar scene featuring vocals by Demis Roussos.[37] A 35th anniversary LP of the original soundtrack was released on Record Store Day 2017.[38]

1492: Conquest of Paradise

In 1992, Paramount Pictures released the film 1492: Conquest of Paradise, also directed by Ridley Scott, as a 500th anniversary commemoration of Christopher Columbus' voyage to the New World. Vangelis's score was nominated as "Best Original Score – Motion Picture" at the 1993 Golden Globe awards, but was not nominated for an Academy Award.[39] However, due to its success Vangelis won an Echo Award as "International Artist Of The Year", and RTL Golden Lion Award for the "Best Title Theme for a TV Film or a Series" in 1996.[40]

Other works

Carl Sagan's TV series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage (1980)[29] uses several pieces composed by Vangelis during the 1970s, including the series' opening theme, the third movement of Heaven and Hell.[29] In 1986, Vangelis was actively involved in the composition of new music for a special edition.[26] Vangelis recalls he was sent by Sagan some sounds collected by satellites, which were exactly what he heard as a child.[3]

During 1980, six years after Vangelis decided against joining Yes, he and the group's lead singer, Jon Anderson, released their first album together, Short Stories, performing under the band name of Jon & Vangelis.[29] They went on to release three more albums; The Friends of Mr Cairo, Private Collection and Page of Life released in 1981, 1983, and 1991 respectively.[41][42][43][44]

In 1981 Vangelis provided the score for Pablo Picasso Painter, a documentary by Frédéric Rossif. It was the third such score by Vangelis as he'd previously scored documentaries about Georges Mathieu and Georges Braque. In 1982 he composed the score of Missing directed by Costa-Gavras, which was awarded the Palme d'Or and gained Vangelis a nomination in the BAFTA Award for Best Film Music category.[41] Other Vangelis film soundtracks include Antarctica for the film Nankyoku Monogatari in 1983, one of the highest-grossing movies in Japan’s film history,[42] and The Bounty in 1984.[27]

Vangelis collaborated in 1981 and 1986 with Italian singer Milva achieving success, especially in Germany, with the albums Ich hab' keine Angst and Geheimnisse (I have no fear and Secrets). An Italian language Nana Mouskouri album featured her singing Vangelis composition "Ti Amerò". Collaborations with lyricist Mikalis Bourboulis, sung by Maria Farantouri, included the tracks "Odi A", "San Elektra", and "Tora Xero".[35]

In the early 1980s Vangelis began composing for ballet and theatre stage plays.[42] In 1983 he wrote the music for Michael Cacoyannis' staging of the Greek tragedy Elektra which was performed with Irene Papas at the open-air amphitheater at Epidavros in Greece.[42] The same year Vangelis composed his first ballet score, for a production by Wayne Eagling. It was originally performed by Lesley Collier and Eagling himself at an Amnesty International gala at the Drury Lane theatre.[42] In 1984 the Royal Ballet School presented it again at the Sadler's Wells theatre. In 1985 and 1986, Vangelis wrote music for two more ballets: "Frankenstein – Modern Prometheus"[26] and "The Beauty and the Beast".[28] In 1992, Vangelis wrote the music for the Euripides play, Medea, that featured Irene Papas.[43][45] In 2001 he composed for a third play which starred Papas, and for The Tempest by Hungarian director György Schwajdas.[46]

Vangelis wrote the score for the 1992 film Bitter Moon directed by Roman Polanski, and The Plague directed by Luis Puenzo.[43][47] In the 90s, Vangelis scored a number of undersea documentaries for French ecologist and filmmaker, Jacques Cousteau, one of which was shown at the Earth Summit.[43][48] The score of the film Cavafy (1996) directed by Yannis Smaragdis,[43] gained an award at the Flanders International Film Festival Ghent and Valencia International Film Festival[40]

World and Olympic Games

The Sport Aid (1986) TV broadcast was set to music specially composed by Vangelis.[26] He conceived and staged the ceremony of the 1997 World Championships in Athletics which were held in Greece. He also composed the music, and designed and directed the artistic Olympic flag relay portion ("Handover to Athens"), of the closing ceremonies of the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney.[49] While no official recording of this composition exists, the music can be heard accompanying the presentation of the emblem of the 2004 Athens Games. In 2002, Vangelis created the official Anthem for the 2002 FIFA World Cup.[50] His work from Chariots of Fire was heard during the 2012 Summer Olympics opening ceremony.[51]

2000s Mythodea, El Greco, Rosetta

In 2001 Vangelis performed live, and subsequently released, the choral symphony Mythodea, which was used by NASA as the theme for the Mars Odyssey mission. This is a predominantly orchestral rather than electronic piece that was originally written in 1993.[52] In 2004, Vangelis released the score for Oliver Stone's Alexander, continuing his involvement with projects related to Greece.[3][53]

Vangelis released two albums in 2007; the first was a 3-CD set for the 25th anniversary of Blade Runner, titled Blade Runner Trilogy and second was the soundtrack for the Greek movie, El Greco directed by Yannis Smaragdis, titled El Greco Original Motion Picture Soundtrack.[54][55][56]

On 11 December 2011, Vangelis was invited by Katara's Cultural Village in the state of Qatar to conceive, design, direct, and compose music for the opening of its world-class outdoor amphitheater. The event was witnessed by a number of world leaders and dignitaries participating in the 4th Forum of the United Nations Alliance of Civilizations held in the city of Doha. British actor Jeremy Irons performed in the role of master of ceremonies, and the event featured a light show by German artist Gert Hof. It was filmed for a future video release by Oscar-winning British filmmaker Hugh Hudson.[15][57]

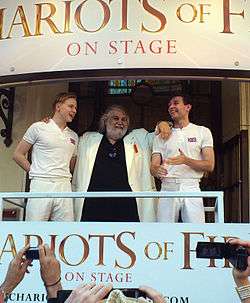

In 2012, Vangelis re-tooled and added new pieces to his iconic Chariots of Fire soundtrack, for use in the same-titled stage adaptation.[15][58] He composed the soundtrack of the environmental documentary film Trashed (2012) directed by Candida Brady, which starred Jeremy Irons.[59] A documentary film called Vangelis And The Journey to Ithaka was released in 2013.[5] He also scored the music for the film Twilight of Shadows (2014) directed by Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina.[60]

For the 12 November 2014 landing of the Philae lander on Comet 67P (part of the European Space Agency's Rosetta mission), Vangelis composed three short pieces titled "Arrival", "Rosetta's Waltz", and "Philae's Journey". The pieces were released online as videos accompanied by images and animations from the Rosetta mission.[61] He was quoted by ESA as saying, "Mythology, science and space exploration are subjects that have fascinated me since my early childhood. And they were always connected somehow with the music I write". In September 2016, the works were released as part of the new studio album Rosetta.[62] In 2018, Vangelis composed an original score for the Stephen Hawking's memorial. While the Hawking's ashes were interred at Westminster Abbey, the music which backed Hawking's words were beamed by ASE to the nearest black hole to Earth.[63][64] It was a personal tribute by Vangelis,[65] and a limited CD titled "The Stephen Hawking Tribute" was shared with the family and over 1,000 guests.[66]

Personal life

For an artist of his stature, very little is known about Vangelis' personal life and he rarely gives official interviews to journalists.[16] However, in a 2005 interview with The Daily Telegraph, Vangelis talked openly about various parts of his life. He stated in the interview that he was "never interested" in the "decadent lifestyle" of his band days, choosing not to use alcohol or other drugs.[3] At the time of the Telegraph interview, Vangelis was involved in his third long-term relationship. When asked why he had not had children, Vangelis replied:

…Because of the amount of travelling I do and the nonsense of the music business, I couldn't take care of a child in the way I think it should be taken care of.[3]

It is not publicly known where Vangelis generally resides; he has stated that he "travels around", rather than settling down in one specific place or country for long periods of time. As a hobby, Vangelis enjoys painting; his first art exhibition of 70 paintings was held at Almudin in Valencia, Spain in 2003 and then toured South America until the end of 2004.[3][15][67][68]

Excerpts from other interviews mention that Vangelis has been married twice before. In a 1976 interview with Dutch music magazine Oor, the author wrote that Vangelis had a wife named Veronique Skawinska, a photographer who had done some album art work for Vangelis.[14][69] An interview in 1982 with Backstage music magazine suggests that Vangelis had previously been married to a singer named Vana Verouti,[70][71] who had performed vocals on some of his records, performing for the first time with him on La Fête sauvage and later on Heaven and Hell.

Musical style and compositional process

The musical style of Vangelis is diverse; although he primarily uses electronic music instruments, which characterize electronic music, his music has been described as a mixture of electronica,[72] classical (his music is often symphonic), progressive rock,[73] jazz (improvisations),[16] ambient,[73][74] avant-garde/experimental,[73][75] world,[16][76] and new-age.[75] Vangelis is often categorized as a New-age composer, but some consider it an erroneous classification. Vangelis considers it a style which "gave the opportunity for untalented people to make very boring music".[3]

As a musician who has always composed and played primarily on keyboards, Vangelis relies heavily on synthesizers[77] and other electronic approaches to music. However, he also plays and uses many acoustic instruments (including folk[1]) and choirs:

I don't always play synthesizers. I play acoustic instruments with the same pleasure. I'm happy when I have unlimited choice; in order to do that, you need everything from simple acoustic sounds to electronic sounds.[16] Sound is sound and vibration is vibration, whether from an electronic source or an acoustic instrument.[15]

Synthtopia, an electronic music review website, stated that Vangelis' music could be referred to as "symphonic electronica"[1] because of his use of synthesizers in an orchestral fashion. The site went on to describe his music as melodic: "drawing on the melodies of folk music, especially the Greek music of his homeland".[78] Vangelis' music and compositions have also been described as "...a distinctive sound with simple, repetitive yet memorable tunes against evocative rhythms and chord progressions."[79] His first electric instrument was a Hammond B3 organ, while first synthesizer a Korg 700 monophonic.[6] He has often used vibrato on his synthesizers, which was carried out in a distinctive way on his Yamaha CS-80 polyphonic synthesizer – varying the pressure exerted on the key to produce the expressive vibrato sound. In a 1984 interview Vangelis described the CS-80 as "The most important synthesizer in my career — and for me the best analogue synthesizer design there has ever been."[6]

In an interview with Soundtrack, a music and film website, Vangelis talked about his compositional processes. For films, Vangelis stated that he would begin composing a score for a feature as soon as he sees a rough cut of the footage.[80] In addition to working with synthesizers and other electronic instruments, Vangelis also works with and conducts orchestras. For example, in the Oliver Stone film Alexander, Vangelis conducted an orchestra that consisted of various classical instruments including sitars, percussion, finger cymbals, harps, and duduks.[81]

He explains his customary method of approach. As soon as the musical idea is there, as many keyboards as possible are connected to the control-desk, which in turn are directly connected to the applicable tracks of the multi-track machine. The idea now is to play as many keyboards as possible at the same time. That way, as broad a basis as possible develops, which only needs fine-tuning. After that it's a question of adding things or leaving out things.[82]

Vangelis once used digital sampling keyboard E-mu Emulator.[6] While acknowledging that computers are "extremely helpful and amazing for a multitude of scientific areas", he describes them as "insufficient and slow" for the immediate and spontaneous creation and, in terms of communication, "the worst thing that has happened for the performing musician".[15][6] He considers that the contemporary civilization is living in a cultural "dark age" of "musical pollution". He considers musical composing a science rather than an art, similar to Pythagoreanism.[3] He has a mystical viewpoint on music as "one of the greatest forces in the universe",[15][83] that the "music exists before we exist".[3] Some consider that his experience of music is a kind of synaesthesia.[3]

Honours and legacy

In 1989 he received the Max Steiner Award.[40] France made Vangelis a Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters in 1992 and promoted him to Commander in 2017,[84] as well Chevalier de la Legion d’ Honneur in 2001.[85][86] In 1993 he received the music award Apollo by Friends of the Athens National Opera Society.[40] In 1995, Vangelis had a minor planet named after him (6354 Vangelis) by the International Astronomical Union's Minor Planet Center (MPC) at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory; the name was proposed by the MPC's co-director, Gareth V. Williams, rather than by the object's original discoverer, Eugène Joseph Delporte, who died in 1955, long before the 1934 discovery could be confirmed by observations made in 1990.[87] In 1996 and 1997 was awarded at World Music Awards.[40]

NASA conferred their Public Service Medal to Vangelis in 2003. The award is the highest honour the space agency presents to an individual not involved with the American government.[88] Five years later, in 2008, the board of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens voted to make Vangelis an Honorary Doctor, making him Professor Emeritus at their Faculty of Primary Education.[89] In June 2008, the American Hellenic Institute honoured Vangelis with an AHI Hellenic Heritage Achievement Award for his "exceptional artistic achievements" as a pioneer in electronic music and for his lifelong dedication to the promotion of Hellenism through the arts.[90] On 16 September 2013, he received the honour of appearing on the Greek 80 cent postage stamp, as part of a series of six distinguished living personalities of the Greek Diaspora.[91] In May 2018 the University of Thessaly in Vangelis' hometown of Volos awarded him an Honorary Doctorate degree in Electrical and Computer Engineering.[92]

AFI

The American Film Institute nominated Vangelis' scores for Blade Runner and Chariots of Fire for their list of the 25 greatest film scores.[93]

Discography

- (1970) Sex Power (Soundtrack)

- (1971) The Dragon (album)

- (1972) Fais Que Ton Rêve Soit Plus Long Que la Nuit (Poème Symphonique)

- (1973) L'Apocalypse des Animaux (Soundtrack)

- (1973) Earth

- (1975) Ignacio – Do You Hear the Dogs Barking (Soundtrack)

- (1975) Heaven and Hell

- (1976) La Fête Sauvage (Soundtrack)

- (1976) Albedo 0.39

- (1977) Spiral

- (1978) Beaubourg

- (1978) Hypothesis (unofficial)

- (1979) China

- (1979) Opera Sauvage (Soundtrack)

- (1980) See You Later

- (1981) Chariots of Fire (Soundtrack)

- (1982) Blade Runner (Soundtrack)

- (1983) Antarctica (Soundtrack)

- (1984) Soil Festivities

- (1984) The Bounty (Soundtrack)

- (1985) Mask

- (1985) Invisible Connections

- (1988) Direct

- (1990) The City

- (1992) 1492: Conquest of Paradise (Soundtrack)

- (1995) Foros Timis Ston Greco

- (1995) Voices

- (1996) Oceanic

- (1998) El Greco

- (2001) Mythodea – Music for the NASA Mission: 2001 Mars Odyssey

- (2004) Alexander (Soundtrack)

- (2007) Blade Runner Trilogy: 25th Anniversary (Soundtrack)

- (2007) El Greco: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack

- (2012) Chariots of Fire – The Play: Music From The Stage Show

- (2016) Rosetta

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Thomas S. Hischak (2015). The Encyclopedia of Film Composers. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 386–388. ISBN 9781442245501.

- ↑ "Prog Reviews review of 666". Ground & Sky. 5 January 2008. Archived from the original on 24 January 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Peter Culshaw (6 January 2005). "My Greek odyssey with Alexander". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ Jason Ankeny. "Vangelis Biography". All Music. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- 1 2 "Vangelis And The Journey to Ithaka Documentary Now Available". Synthtopia. 4 December 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dan Goldstein (November 1984), "Soil Festivities Vangelis Speaks", Electronics & Music Maker, retrieved 22 August 2016

- ↑ Doerschuk, Bob. "Oscar-winning Synthesist, Interview by Bob Doerschuk". Nemo Studios. Archived from the original on 2017-12-22. Retrieved 2017-12-25.

- ↑ "Vangelis - The Composer Who Set Chariots Afire". Life. 5 (7). July 1982. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ↑ Yves Bigot (January 1984). "Vangelis analyses his syntheses". Guitare & Claviers. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ↑ Steve Lake (10 August 1974). "Greek Group: Vangelis Papathanassiou is one of those rare rock characters - an eccentric. Will this ex-keyboard player of Aphrodite's Child join Yes? Steve Lake meets the man himself". Melody Maker. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- 1 2 "The Forminx". Vangelis Movements. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- 1 2 Blue Point Retrieved 11 October 2008

- ↑ Prog Archives bio of AC Retrieved 21 August 2008

- 1 2 Elsewhere Oor Retrieved 12 October

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Allegra Donn (1 July 2012). "Vangelis: why Chariots of Fire's message is still important today". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 John Schaefer (June 1985). "New Sounds". Spin. Vol. 1 no. 2. p. 49. ISSN 0886-3032.

- 1 2 3 "Nemo: Vangelis - chapter 1". nemostudios.co.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ Album review Retrieved 20 August 2008

- ↑ Groove NL reviews Retrieved 2 September 2008

- ↑ "New On The Charts - Jon and Vangelis". Billboard. 92 (35): 31. 30 August 1980. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ Alt.music FAQ Yes Retrieved 2 September 2008

- ↑ Nemo Studios Retrieved 7 April 2010

- 1 2 "Nemo: Vangelis - chapter 2". nemostudios.co.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Nemo: Vangelis - chapter 3". nemostudios.co.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ All Music review of Opera. Retrieved 2 September 2008

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Nemo: Vangelis - chapter 8". nemostudios.co.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Nemo: Vangelis - chapter 7". nemostudios.co.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Nemo: Vangelis - chapter 9". nemostudios.co.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Nemo: Vangelis - chapter 4". nemostudios.co.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ "Nemo: Vangelis - chapter 11". nemostudios.co.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ "Nemo: Vangelis - chapter 12". nemostudios.co.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ AMG review of Chariots of Fire Retrieved 25 September 2008

- ↑ Vangelis' Blade Runner film score Retrieved 12 February 2012

- ↑ Synthtopia BR review Retrieved 27 November 2008

- 1 2 Intuitive Music – Vangelis biog. Archived 7 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 25 September 2008

- ↑ Answers.com review Retrieved 25 September 2008

- ↑ Play.com BR Tri. Product page Retrieved 20 August 2008

- ↑ "RSD '17 Special Release: Vangelis - Blade Runner Original Soundtrack". recordstoreday.com. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ↑ 1492: Conquest of Paradise soundtrack review at Filmtracks.com Retrieved 25 September 2008

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Vangelis Papathanassiou by Gus Leous". Newsfinder.Org. 7 March 2003. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- 1 2 "Nemo: Vangelis - chapter 5". nemostudios.co.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Nemo: Vangelis - chapter 6". nemostudios.co.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Nemo: Vangelis - chapter 10". nemostudios.co.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ Conolly discography of J&V Retrieved 25 September 2008

- ↑ Dennis Lodewijks. "Elsewhere: Other Music". elsew.com. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ↑ "Nemo: Vangelis - chapter 13". nemostudios.co.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ Internet Movie Database Retrieved 13 April 2012

- ↑ Proggnosis Web-site Retrieved 25 September 2008

- ↑ Myles Garcia (2014). Secrets of the Olympic Ceremonies. eBookIt. ISBN 9781456608088.

- ↑ Prog archives single Retrieved 26 September 2008

- ↑ Sophia Heath (19 June 2012). "London 2012 Olympics: the full musical playlist for the Olympic opening ceremony". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ Tracksounds Review Retrieved 26 September 2008

- ↑ Synthtopia Review of Alex. S.T. Retrieved 26 September 2008

- ↑ "Nemo: Vangelis - chapter 15". nemostudios.co.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ Synthopia Trilogy Preview Retrieved 26 September 2008

- ↑ Elsewhere albums page Retrieved 26 September 2008

- ↑ Peter Townson (13 December 2011). "Cultural village amphitheatre opens with inspiring concert". Gulf Times. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ↑ Jasper Rees (3 May 2012). "Chariots of Fire: The British are coming... again". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ Leo Hickman (11 December 2012). "Jeremy Irons talks trash for his new environmental documentary". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ Alejandro Clavijo (14 May 2014). "Vangelis compone la banda sonora de la última película del director argelino Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina". Reviews New Age. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ Claudia (19 December 2014). "Music Of The Irregular Spheres". European Space Agency. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ "Rosetta CD". uDiscover. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ "Stephen Hawking's words will be beamed into space". BBC. 14 June 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ↑ "Stars turn out for Stephen Hawking memorial at Westminster Abbey". BBC. 15 June 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ↑ "The Stephen Hawking Tribute CD". The Stephen Hawking Foundation UK. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- ↑ Elizabeth Elkin, Hilary Clarke and Brandon Griggs (15 June 2018). "Stephen Hawking's voice bound for a black hole 3,500 light years away". CNN. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- ↑ "Nemo: Vangelis - chapter 14". nemostudios.co.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ "Vangelis Paintings". Vangelis Movements. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ↑ Vangelis collector Telegraph interview Retrieved 12 October 2008

- ↑ Elsewhere Backstage Retrieved 12 October 2008

- ↑ According to the Vangelis Movements website not mentioning marriage to Vana, she is reported to have played again recently (2012). This website refer's to Vana's own website, and includes images of Vangelis and Vana together.

- ↑ "Rediscover Vangelis' 'See You Later'". uDiscover. 29 February 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 Mike G. "Vangelis". Ambient Music Guide. Mike Watson aka Mike G. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ "Ambient In 20 Songs". uDiscover. 5 May 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- 1 2 Mike Orme (7 February 2008). "Blade Runner Trilogy: 25th Anniversary". Pitchfork. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ "Rediscover China". uDiscover. 30 September 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ "Nemo Studios: Portrait of a studio". Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ↑ "Review of Vangelis". Synthtopia. 17 January 2004. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- ↑ Mfiles biog. Retrieved 6 October 2008

- ↑ Soundtrack Interview Retrieved 6 October 2008

- ↑ MFTM review of Alexander Retrieved 6 October 2008 Archived 19 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Vangelis interview to Music Maker magazine, September 1982 Retrieved 20 August 2008

- ↑ "Greek composer Vangelis says music shaped space". CNN. 4 July 2001. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ "Vangelis is "Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres" (Commander in the Order of Arts and Letters)". mounarebeiz.com. 3 July 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ Alexander the Great website Retrieved 25 September 2008

- ↑ Jacqueline A. Schaap (21 June 2004). "Vangelis copyright BUMA and STEMRA" (PDF). Commission of the European Communities. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ Minor Planet Center web-site with info about the planet Retrieved 25 September 2008

- ↑ Sonic State bio of Vangelis Retrieved 25 September 2008

- ↑ Elsew web-site Retrieved 20 August 2008

- ↑ American Hellenic website Retrieved 22 February 2009

- ↑ Papantoniou, Margarita (17 September 2013). "Six Greek Diaspora Personalities on Postal Stamps | GreekReporter.com". Greece.greekreporter.com. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ "Honorary Doctorate degree for Vangelis". Elsewhere. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ↑ AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores Ballot

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Vangelis |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vangelis. |

- Vangelis on IMDb

- Independent Vangelis Site

- Vangelis' Movements

- Vangelis Collector

- Vangelis' Nemo Studios

- Vangelis History

- Interview with Vangelis from Den of Geek

- Interview with Vangelis on composing Chariots of Fire from BBC Four's Sound of Cinema