The Minority Report

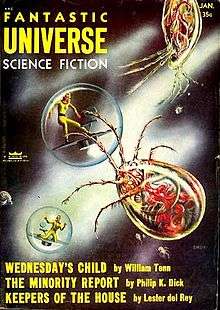

"The Minority Report" is a 1956 science fiction short story by American writer Philip K. Dick, first published in Fantastic Universe. In a future society, three mutants foresee all crime before it occurs. Plugged into a great machine, these "precogs" allow the Precrime Division to arrest suspects prior to any infliction of public harm. When the head of Precrime, John A. Anderton, is accused of murdering Leopold Kaplan, a man whom he has never met, Anderton is convinced a great conspiracy is afoot. His new assistant, Ed Witwer, must have corrupted the system in an attempt to oust him from the position. On the run and suspicious of even his wife, Anderton searches for the minority report to clear his name, as only two out of the three precogs predicted his guilt. Through a series of betrayals and changing alliances, Anderton discovers that the three predictions are rather a progression of alternate realities. To maintain Precrime's authority, Anderton consciously decides to kill Kaplan, thereby affirming the validity of the second majority report. Anderton is thus exiled with his wife to life on a frontier colony and replaced by Witwer as head of Precrime. The story ends with Anderton's advice to his successor: "Better keep your eyes open. It might happen to you at any time."

The story reflects many of Philip K. Dick's personal Cold War anxieties, particularly questioning the relationship between authoritarianism and individual autonomy. Like many stories dealing with knowledge of future events, "The Minority Report" questions the existence of free will.

In 2002, the story was adapted into a film directed by Steven Spielberg and starring Tom Cruise, Colin Farrell and Max von Sydow. Spielberg's film was followed by a series of the same name, which debuted on the FOX Network on September 21, 2015.

Synopsis

John Anderton is the head of the Precrime Division. One day, he receives a report that he is going to murder Leopold Kaplan, a man he never met. At first he goes on the run, but later turns to the offensive to figure out why the precogs identified him as a killer. He finds out that General Kaplan is pushing to abolish the Division, claiming that it is not accurate. Giving himself up, he meets with Kaplan at a rally where he is used as an example of the ineffectiveness of Precrime to bolster Kaplan's position. To everyone's surprise, Anderton pulls out a gun and kills Kaplan. He and his wife are exiled to an off-planet concentration camp.

On the way there, Anderton explains his reasoning. After obtaining the precog reports he realized that one minority report said that he would not kill Kaplan. He realizes that each report is based on him having knowledge of the other reports. In the first report he kills Kaplan to prevent Precrime from being shut down. The second report has a narrative where, after reading the first report, he decides not to shoot the general and spare his family imprisonment. The final report details how Kaplan was planning a military coup to install martial law in place of Precrime, leading Anderton to the decision that he has to assassinate Kaplan. Realizing that this is the lesser of two evils, Anderton decides to follow the path described to him in the third report and kills Kaplan.

Precrime

Precrime is a predictive policing system dedicated to apprehending and detaining people before they have the opportunity to commit a given crime. At the time of the story, it has been operating for thirty years. This method has replaced the traditional system of discovering a crime and its perpetrator after the crime has already been committed, then issuing punishment after the fact. As Witwer says early on in the story, "punishment was never much of a deterrent and could scarcely have afforded comfort to a victim already dead". Unlike the film adaptation, the story version of Precrime does not deal solely with cases of murder, but all crimes. As Commissioner John A. Anderton (the founder of Precrime) states, "Precrime has cut down felonies by 99.8%."

Three mutants, known as precogs, have precognitive abilities they can use to see up to two weeks into the future. The precogs are strapped into machines, nonsensically babbling as a computer listens and converts this gibberish into predictions of the future. This information is transcribed onto conventional punch cards that are ejected into various coded slots. These cards appear simultaneously at Precrime and the army headquarters to prevent systemic corruption.[1]

Precogs

Precogs are mutants, identified talents further developed in a government-operated training school — for example, one precog was initially diagnosed as "a hydro-cephalic idiot" but the precog talent was found under layers of damaged brain tissue. The precogs are kept in rigid position by metal bands, clamps and wiring, strapping them into special high-backed chairs. Their physical needs are taken care of automatically and Anderton claims that they have no spiritual needs. Their physical appearance is distorted from an ordinary human, with enlarged heads and wasted bodies. Precogs are "deformed" and "retarded" as "the talent absorbs everything"; "the esp-lobe shrivels the balance of the frontal area". They do not understand their predictions; only through technological and mechanical aid can their nonsense be unraveled. The data produced does not always pertain to crime or murder, but this information is then passed on to other groups of people who use the precog necessities to create other future necessities.

Majority and minority reports

Each of the three precogs generates its own report or prediction. The reports of all the precogs are analyzed by a computer and, if these reports differ from one another, the computer identifies the two reports with the greatest overlap and produces a "majority report", taking this as the accurate prediction of the future. But the existence of majority reports implies the existence of a "minority report". In the story, Precrime Police Commissioner John A. Anderton believes that the prediction that he will commit a murder has been generated as a majority report. He sets out to find the minority report, which would give him an alternate future.

However, as Anderton finds out, sometimes all three reports differ quite significantly, and there may be no majority report, even though two reports may have had enough in common for the computer to link them as such. In the storyline, all of the reports about Anderton differ because they predict events occurring sequentially, and thus each is a minority report. Anderton's situation is explained as unique, because he, as Police Commissioner, received notice of the precogs' predictions, allowing him to change his mind and invalidate earlier precog predictions.

Multiple time paths

The existence of three apparent minority reports suggests the possibility of three future time paths, all existing simultaneously, any of which an individual could choose to follow or be sent along following an enticement (as in Anderton's being told he was going to murder an unknown man). In this way, the time-paths overlap, and the future of one is able to affect the past of another. It is in this way that the story weaves a complicated web of crossing time paths and makes a linear journey for Anderton harder to identify. This idea of multiple futures lets the precogs of Precrime be of benefit—because if only one time-path existed, the predictions of the precogs would be worthless since the future would be unalterable. Precrime is based on the notion that once one unpleasant future pathway is identified, an alternative, better one can be created with the arrest of the potential perpetrator.

Police Commissioner John A. Anderton

John A. Anderton is the protagonist of The Minority Report. At first, he is highly insecure, suspicious of those closest to him - his wife, his assistant Witwer. He has complete faith in the Precrime system and its authority over individuals and their freedom of choice. The poor living condition of the precogs and the imprisonment of would-be criminals are necessary consequences for the greater good of a safe society. When his own autonomy comes under attack, Anderton retains this faith and convinces himself that the system has somehow been corrupted.

Anderton struggles to find an appropriate balance between Precrime authority and individual liberty. Ultimately, Anderton decides to kill Leopold Kaplan to affirm the majority report and thereby preserve the validity of the Precrime system.

Media adaptation

- The 2002 film Minority Report directed by Steven Spielberg and with Tom Cruise as main actor, was based on the story.

- A video game, Minority Report: Everybody Runs, published in 2002 by Activision, was based on the film.

- A sequel television series, more than a decade after the events of the movie and also titled Minority Report, premiered on FOX[2] on September 21, 2015.[3]

Differences between short story and film

- While the film uses the backdrop of Washington, D.C., Baltimore and Northern Virginia, the location of the original story is New York City.

- In the story, John Anderton is a 50-year-old balding, out-of-shape police officer who created Precrime, while in the movie Anderton is in his late 30s, handsome, drug addict, athletic, with a full head of hair who joined Precrime after his son's kidnapping. Instead, a man named Lamar Burgess creates Precrime. His wife in the short story is named Lisa, while his ex-wife in the film is named Lara.

- The precogs were originally named Mike, Donna, and Jerry, and were deformed and intellectually disabled. In the adaptation, they are called Agatha, Dashiell, and Arthur — after crime writers Agatha Christie, Dashiell Hammett, and Arthur Conan Doyle — children of drug addicts whose mutations led them to dream of future murders, which are captured by machines. They are "deified" by the Precrime officers, and are implied to be intelligent (Agatha guides Anderton successfully through a crowded mall while being pursued by Precrime, and the trio are seen reading large piles of books at the end of the film). In the end of the movie they retire to a rural cottage where they continue their lives in freedom and peace.

- In the short story, the precogs can see other crimes, not just murder. In the movie, the precogs can only clearly see murder.

- In the short story, Anderton's future victim is General Leopold Kaplan, who wants to discredit Precrime in order to replace this police force with a military authority. At the end of the story, Anderton kills him to prevent the destruction of Precrime. In the movie, Anderton is supposed to kill someone named Leo Crow, but later finds out Crow is just part of a set up to prevent Anderton from discovering a different murder that his superior, Lamar Burgess, committed years ago. At the end of the film, Anderton confronts Burgess, who commits suicide and sends Precrime into oblivion.

- In the short story, Anderton seeks the precogs to hear their "minority reports". In the movie, Anderton kidnaps a precog in order to discover his own "minority report" and extract the information for a mysterious crime.

- In the film, a major plot point was that there was no minority report. The story ends with Anderton describing how the minority report was based on his knowledge of the other two reports.

- The short story ends with Anderton and Lisa exiled to a space colony after Kaplan's murder. The movie finishes with John and Lara reunited after the conspiracy's resolution, expecting a second child.[4][5][6]

References

Philip K. Dick: Minority Report (Gollancz: London, 2002) ( ISBN 1-85798-738-1 or ISBN 0-575-07478-7) (contains nine short stories by Dick, including most of those that were adapted into films. Also released in audio book form ISBN 0-06-009526-1 containing only five stories, read by Keir Dullea)

- ↑ Dick, Philip K. (2002). Selected Stories of Philip K. Dick. New York: Pantheon.

- ↑ Andreeva, Nellie (September 8, 2014). "Fox Nabs 'Minority Report' Series From Steven Spielberg's Amblin TV With Big Put Pilot Commitment". Deadline Hollywood. Penske Business Media, LLC. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ↑ Prudom, Laura (September 18, 2015). "Nick Zano joins Fox's 'Minority Report'". Variety. Penske Business Media, LLC. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ↑ "The Duck Speaks: Minority Report". Archived from the original on 2007-05-05. Retrieved 2007-03-25.

- ↑ "Comparison Paper on Minority Report: "From Story to Screen"". Retrieved 2007-03-25.

- ↑ Landrith, James (2004-04-12). "The Minority Report: In Print and On Screen". Retrieved 2007-03-25.

External links

- The Minority Report title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- precrime