Sampling (music)

In music, sampling is the reuse of a portion or sample of a sound recording in another recording. Samples may comprise rhythm, melody, speech, or other sounds, and are integrated using digital hardware (samplers) or software such as digital audio workstations.

A process similar to sampling originated in the 1940s with musique concrète, experimental music created by splicing, manipulating and looping tape. The term sampling was coined by in the late 1970s by the creators of the Fairlight CMI, an influential early sampler that became a staple of 1980s pop music. The 1988 release of the first Akai MPC, an affordable sampler with an intuitive interface, made sampling accessible to a wider audience and had a major influence on the development of electronic and hip hop music.

Sampling is a foundation of hip hop music, which emerged in the 1980s, with producers sampling funk and soul records, particularly drum breaks, which could then be rapped over. Musicians have created albums assembled entirely from samples, such as DJ Shadow's 1996 album Endtroducing. The practice has influenced all genres of music and is particularly important to electronic music, hip hop and pop.

Sampling without permission can infringe copyright. The process of acquiring permission is known as sample clearance. Landmark legal cases, such as Grand Upright Music, Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records Inc in 1991, changed how samples are used. As the court ruled that unlicensed sampling constitutes copyright infringement, samples from well-known sources are now often prohibitively expensive.

History

Origins

In the 1940s, Pierre Schaeffer developed musique concrète, an experimental form of music created by recording sounds to tape, splicing them, and manipulating them to create sound collages. He created pieces using recordings of sounds including the human body, locomotives, and kitchen utensils.[1] The method also involved the creation of tape loops, splicing lengths of tape end to end, by which a sound could be played indefinitely.[1] Schaeffer developed a tape recorder, the Phonogene, which played loops at twelve different pitches triggered by a keyboard.[1]

Composers including John Cage, Edgar Varèse, Karheinz Stockhausen and Iannis Xenakis experimented with musique concrète,[1] and Bebe and Louis Barron used it to create the first totally electronic film soundtrack, for the 1956 science fiction film Forbidden Planet. It was brought to a mainstream audience by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, which used these early sampling techniques to produce soundtracks for shows including Doctor Who.[1]

In the 1960s, Jamaican dub reggae producers such as King Tubby and Lee "Scratch" Perry began using pre-recorded samples of reggae rhythms to produce riddim tracks, which were then deejayed over.[2][3] Jamaican immigrants introduced dub sampling techniques to American hip hop music in the 1970s.[3]

Samplers

The term sampling was coined by in the late 1970s by Kim Ryrie and Peter Vogel to describe a feature of their Fairlight CMI synthesizer.[1] While developing the Fairlight, Vogel sampled around a second of a piano piece from a radio broadcast, and discovered that he could imitate a real piano by playing the sample back at different pitches. He recalled in 2005:

It sounded remarkably like a piano, a real piano. This had never been done before ... By today's standards it was a pretty awful piano sound, but at the time it was a million times more like a piano than anything any synthesiser had churned out. So I rapidly realised that we didn't have to bother with all the synthesis stuff. Just take the sounds, whack them in the memory and away you go.[4]

Ryrie and Vogel saw using recordings of sounds instead of generating them through synthesis as "cheating" and were not proud of the method.[5] According to Sound on Sound, one music technology magazine dismissed the feature as a gimmick.[1] Compared to later samplers, the Fairlight offered limited control over samples; it allowed control over pitch and envelope, and only allowed recording of a few seconds' of sound. However, its ability to sample and play back acoustic sounds became its most popular feature.[1] Though the concept of reusing recordings in larger recordings was not new, the Fairlight's built-in sequencer and design made the concept accessible.[1] According to the Guardian, the Fairlight was the "first truly world-changing sampler".[6] Though it was It was unaffordable for most hobbyists, early users included Kate Bush, Peter Gabriel, Thomas Dolby, Duran Duran, Herbie Hancock, Todd Rundgren, Icehouse and Ebn Ozn.[7]

The success of the Fairlight inspired competitors to produce their own samplers, improving the technology and driving down prices dramatically.[1] Early competitors included the E-mu Emulator[1] and the Akai S950.[7] In 1988, Akai released the MPC 60.[8] The MPC allowed artists to assign samples to separate pads and trigger them independently, similarly to playing a traditional instrument such as a keyboard or drum kit.[9] It had a major influence on the development of electronic and hip hop music,[10][11] allowing musicians and producers to create elaborate tracks without instruments, a studio, or formal music knowledge.[11] Today, most samples are made and edited using digital audio workstations such as Ableton Live.[12]

Impact

Sampling has influenced all genres of music[6] and is an important part of many musical genres, including hip hop, pop, and electronic music.[13] Commonly sampled elements include strings, basslines, drum loops, vocal hooks, or entire bars of music, especially from soul records.[14] Samples may be layered,[15] equalized,[15] sped or slowed, repitched, looped, or otherwise manipulated.[13] As sampling technology progressed, the possibilities for manipulation have grown.[13]

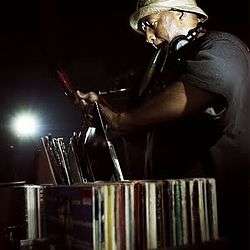

Stevie Wonder's 1979 album Journey Through the Secret Life of Plants has been suggested as the first album to make extensive use of samples.[6] My Life in the Bush of Ghosts (1981) by David Byrne and Brian Eno is cited as an important early work of sampling, incorporating samples of recordings including Arabic singers, radio disc jockeys, and an exorcist.[16] Eno cited Holger Czukay's experiments with dictaphones and shortwave radios as earlier examples of sampling, but felt his and Byrne's innovation had been to make sampling "the lead vocal".[17] Big Audio Dynamite pioneered sampling in rock and pop with their 1985 album This Is Big Audio Dynamite.[18] Producer DJ Shadow used an MPC60 to create his influential 1996 album Endtroducing, which is composed entirely of samples.[19]

Sampling is the foundation of hip hop, which emerged in the 1980s.[20] DJs and producers had long used turntables to mix and loop breaks from funk tracks, which could then be rapped over.[21] Compilation albums such as Ultimate Breaks and Beats comprised tracks with drums-only sequences, intended to be sampled by hip hop producers.[21] The advent of samplers made assembling loops easier.[21] Early hip hop tracks, such as "Rapper's Delight" (1979) and "Planet Rock" (1982), reused elements of other recordings by recreating them rather than sampling them.[13] In 1986, three tracks, "South Bronx", "Erik B is President" and "It's a Demo", sampled the funk and soul tracks of James Brown, particularly a drum break from "Funky Drummer", helping popularize the technique.[13]

In 2008, Guardian journalist David McNamee wrote that in the 1980s sampling had been a political act: "Two record decks and your dad's old funk collection was once the working-class black answer to punk ... Sampling, which once seemed world-ending in the eyes of the music industry, is now non-threatening and a bit passé, particularly with today's availability and ease of original music-making software."[12]

According to the BBC, the most sampled song of all time is "Change the Beat" by Fab Five Freddy, which appears on over 1,2000 tracks.[22] Another common sample comes from a seven-second drum break in the 1969 track "Amen, Brother", known as the Amen break, which became popular first with American hip hop producers and then British jungle producers in the early 1990s.[21] The sample became widely used across genres, used by indie rock bands such as Oasis and in television theme tunes such as that of Futurama.[21]

Legal and ethical issues

Sampling without permission breaches the copyright of the original sound recording, of the composition and lyrics, and of the performances, such as a guitar riff or rhythm. The moral rights of the original artist may also be breached if they are not credited or object to the sampling.[14] In some cases, sampling may be protected under American fair use laws.[14] The process of acquiring legal permission for a sample is known as clearance.[14]

In 1989, the Turtles sued De La Soul for using an uncleared sample on their album 3 Feet High and Rising. Turtles singer Mark Volman told the Los Angeles Times: "Sampling is just a longer term for theft. Anybody who can honesty say sampling is some sort of creativity has never done anything creative."[23] The case was settled out of court and set a legal precedent that led to a decline in sampling in hip hop.[23]

In 1991, songwriter Gilbert O'Sullivan sued rapper Biz Markie after he sampled O'Sullivan's "Alone Again (Naturally)" on his album I Need a Haircut (see Grand Upright Music, Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records Inc.). The court ruled that sampling without permission constituted copyright infringement. Instead of asking for royalties, O'Sullivan forced Biz Markie's label Warner Bros to recall the album until the song was removed.[24] Nelson George described it as the "most damaging example of anti-hip hop vindictiveness", which "sent a chill through the industry that is still felt".[24] According to the Washington Post, "No court decision has changed the sound of pop music as much as this, before or since", likening it to a banning of certain musical instruments.[25]

Following the ruling, samples have typically been taken either from obscure recordings (such as on Endtroducing) or cleared, an often expensive option only available to successful acts.[25] According to the Guardian, "Sampling became risky business and a rich man's game, with record labels regularly checking if their musical property had been tea-leafed."[12] For less successful artists, the legal implications for samples can create confusion. According to Fact, "For a bedroom producer, clearing a sample can be nearly impossible, both financially and in terms of administration."[13]

The Washington Post described the modern use of well-known samples, such as those by Kanye West, as a way of advertising wealth, similarly to flaunting cars or jewellery.[25] West has been sued several times over his use of samples.[13] Though some have accused the law of restricting creativity, others argue it forces producers to innovate.[25] Sampling can help popularize the sampled work. For example, the Desiigner track "Panda" topped the Billboard Hot 100 after West sampled it on "Father Stretch My Hands, Pt. 2".[13]

According to Fact, early hip hop sampling was governed by an "unspoken" set of rules, forbidding sampling records released less than ten years earlier, reissues, other hip hop records, or from non-vinyl sources, among other restrictions.[20] These rules were relaxed as younger producers took over: "For many producers today it is no longer a case of 'should I sample this?' but of 'can I get away with sampling this?'. Thus the ethics of sampling unravelled as the practice became ever more ubiquitous."[20] Richard Lewis Spencer, who owns the copyright for the amen break, has never received royalties for its use and condemned its sampling as "plagiarism" and "bullshit". He likened the situation to "the man who goes to the sperm bank and unknowingly sires hundreds of children".[21]

To circumvent legal problems, producers may recreate a portion of a recording rather than sample it, requiring only the publisher's permission. It may be cheaper to hire a recording company to recreate a portion of music rather than license it. Recreating rather than sampling also allows artists to remove elements, allowing for more creative possibilities.[26]

See also

- Hip hop production

- Interpolation

- Mashup – extensive page illuminating current practices of extensive sampling and their precedents

- Musical quotation - practice of quoting another musical piece in a composition

- Music loop

- Musique concrète – early development of fundamental importance in using recorded sound

- Remix

- Riddim

- Sampler (musical instrument) – hardware and software platforms

- Sampling (signal processing) – Basic PCM theory

- Sound collage – production of new sound material using portions, or samples, of previously made recordings.

- WIPO Copyright and Performances and Phonograms Treaties Implementation Act

- DMG Clearances Inc – A company specializing in sample clearance for over 20 years

Further reading

- Katz, Mark. "Music in 1s and 0s: The Art and Politics of Digital Sampling." In Capturing Sound: How Technology has Changed Music (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 137-57. ISBN 0-520-24380-3

- McKenna, Tyrone B. (2000) "Where Digital Music Technology and Law Collide – Contemporary Issues of Digital Sampling, Appropriation and Copyright Law" Journal of Information, Law & Technology.

- Challis, B (2003) "The Song Remains The Same – A Review of the Legalities of Music Sampling"

- Ratcliffe, Robert. (2014) "A Proposed Typology of Sampled Material within Electronic Dance Music." Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 6(1): 97-122.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sampling (music). |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sampling |

- Samples and Loops at Curlie (based on DMOZ)

- Who Sampled (online database of sampling)

- COVER.INFO – Large database of cover versions, medleys, samples and other musical quotations

- Basic musical elements in terms of audio samples

- SampleSwap.org Sound Sampling Community

- History of early sampling instruments at '120 years of Electronic music'

- How to clear samples (Step by step guide)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "The Lost Art Of Sampling: Part 1". www.soundonsound.com. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- ↑ "Reggae Wisdom: Proverbs in Jamaican Music". Univ. Press of Mississippi – via Google Books.

- 1 2 Bryan J. McCann, The Mark of Criminality: Rhetoric, Race, and Gangsta Rap in the War-On-Crime ERA, pages 41-42, University of Alabama Press

- ↑ Hamer, Mick (26 March 2015). "Interview: Electronic maestros". New Scientist. Reed Business Information. Archived from the original on 8 July 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ↑ "Fairlight – The Whole Story". Audio Media. January 1996.

- 1 2 3 McNamee, David (2009-09-28). "Hey, what's that sound: Sampler". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- 1 2 "A brief history of sampling". MusicRadar. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- ↑ "The 10 most important hardware samplers in history". MusicRadar. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- ↑ "Meet the unassuming drum machine that changed music forever". Vox. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

- ↑ "Hip-hop's most influential sampler gets a 2017 reboot". Engadget. Retrieved 2018-04-03.

- 1 2 "Meet the unassuming drum machine that changed music forever". Vox. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

- 1 2 3 McNamee, David (2008-02-16). "When did sampling become so non-threatening?". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Untangling the knotty world of hip-hop copyright". FACT Magazine: Music News, New Music. 2016-06-25. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- 1 2 3 4 "Sample Clearance". www.soundonsound.com. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- 1 2 "Just a sample". The Economist. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- ↑ Brian Eno and David Byrne, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts | | guardian.co.uk Arts

- ↑ Sheppard, David (July 2001). "Cash for Questions". Q.

- ↑ Myers, Ben (2011-01-20). "Big Audio Dynamite: more pioneering than the Clash?". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "DJ Shadow". Keyboard. New York. October 1997. Archived from the original on 2013-03-20. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Don't kick the ethics out of sampling: picking up the bullets from The Weeknd's clash with Portishead - Page 2 of 2 - FACT Magazine: Music News, New Music". FACT Magazine: Music News, New Music. 2013-08-02. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Seven seconds of fire". The Economist. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- ↑ Eveleth, Rose. "The World's Most Sampled Song Is "Change the Beat" by Fab 5 Freddy". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- 1 2 Runtagh, Jordan (2016-06-08). "Songs on Trial: 12 Landmark Music Copyright Cases". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- 1 2 George, Nelson (2005-04-26). Hip Hop America. Penguin. ISBN 9781101007303.

- 1 2 3 4 Richards, Chris. "The court case that changed hip-hop — from Public Enemy to Kanye — forever". Washington Post. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- ↑ "Steve Gibson & Dave Walters: Recreating Samples". www.soundonsound.com. Retrieved 2018-10-14.