Snatcher (video game)

| Snatcher | |

|---|---|

PC-8801 cover art | |

| Developer(s) | Konami |

| Publisher(s) | Konami |

| Designer(s) | Hideo Kojima |

| Programmer(s) | Toshiya Adachi |

| Artist(s) |

Tomiharu Kinoshita Yoshihiko Ota Hideo Kojima |

| Writer(s) | Hideo Kojima |

| Platform(s) | PC-8801, MSX2, PC Engine, Sega CD, PlayStation, Sega Saturn |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Graphic adventure, visual novel |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Snatcher[lower-alpha 1] is a graphic adventure game developed and published by Konami. It was written and designed by Hideo Kojima and first released in 1988 for the PC-8801 and MSX2 in Japan. Snatcher is set in the future in an East Asian metropolis where humanoid robots dubbed "Snatchers" have been discovered killing humans and replacing them in society. The player takes on the role of Gillian Seed, an amnesiac who joins a Snatcher hunting agency hoping it will help him remember his past. Gameplay is primarily through a menu-based interface through which the player can choose to examine items, search rooms, speak to characters, and perform other actions.

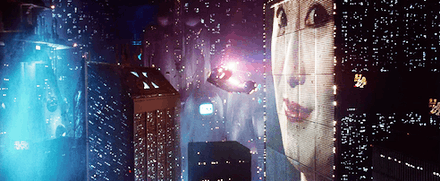

Kojima wanted Snatcher to have a cinematic feel, so the setting and story are heavily influenced by science fiction cinema. The team drew significant inspiration from cyberpunk works, especially Blade Runner (1982). Development on the PC versions took more than twice as long as the average game of the time, even after Kojima was asked to trim more than half his initial story. The game was released to positive reviews, but poor sales. It garnered a cult following, and was remade as a role-playing game, SD Snatcher, for the MSX2. This was followed by a remake of the original adventure game using CD-ROM technology, released for the PC Engine Super CD-ROM² System in 1992.

Looking to provide a more interactive experience to gamers in the West, Konami localized the PC Engine version of Snatcher for the Sega CD in 1994. The game received mostly positive reviews for its cinematic presentation and mature themes which were uncommon in video games at the time. It has been retrospectively acclaimed as both one of the best adventure and cyberpunk games of all time, and identified as a foundation for the themes Kojima explored later in the Metal Gear series. The game was a significant inspiration on Goichi Suda, who worked with Kojima to produce a radio drama prequel, Sdatcher. The English version of Snatcher has never been rereleased, despite desire from fans.

Gameplay

Snatcher is a graphic adventure game with visual novel elements.[1][2][3] The player takes the role of protagonist Gillian Seed as he investigates and hunts "Snatchers", dangerous humanoid robots disguised as humans roaming Neo Kobe City.[1] The game's visuals are static images with some animations that display at the top of the screen. There is no point-and-click interface, all actions are made through a text menu with commands such as Move, Look, and Investigate.[1] The game's puzzles and dialogue trees are simple, lending to an emphasis on linear storytelling.[1] Sometimes character panels are shown below the main graphics window during conversations to convey their facial expressions.[2]

There are a handful of action segments where the player shoots at enemies dispersed across a 3x3 grid. The Sega CD version supports the Justifier light gun that was packaged with Lethal Enforcers for these segments.[1]

Plot

Snatcher is set in the mid-21st century, fifty years after a biological weapon known as Lucifer-Alpha killed much of the world's population. In Neo Kobe City, a metropolis on an artificial island in eastern Asia, humanoid robots dubbed "Snatchers" have been recently discovered killing humans, donning their skin as a disguise, and replacing them in society. The Neo Kobe government closes the city from the outside world and establishes JUNKER, a task force to hunt Snatchers. The player takes on the role of Gillian Seed, an amnesiac who can only remember that his past is somehow related to Snatchers. He starts working at JUNKER in hopes that hunting Snatchers will bring his past to light.

After Gillian Seed arrives at the JUNKER headquarters, he is introduced to Chief Cunningham and receives a robot navigator named "Metal Gear" from JUNKER's engineer Harry Benson. Metal Gear receives a distress call from Jean-Jack Gibson, the only other JUNKER agent, so Gillian travels there with Metal Gear, only to find Gibson massacred by a pair of Snatchers. They try to pursue the Snatchers, but are forced to make a quick escape as the factory explodes. Gillian begins searching for the identity of the Snatchers that murdered Gibson, and after searching Gibson's house and speaking with his informant, he identifies a pair of suspects. When hunting down the Snatchers, he is nearly killed but is saved by Random Hajile, a Snatcher bounty hunter. Random joins Gillian and Metal Gear as they travel to a hospital Gibson identified as suspicious during his investigation.They learn it has been abandoned for several years and harbors a secret basement where they find skeletons of Snatcher victims. Among them, they find Chief Cunningham, meaning the JUNKER chief is a Snatcher. Some Snatchers attack the group, but Random distracts them to allow Gillian and Metal Gear to escape. Back at JUNKER headquarters, Gillian kills the Chief and speak to Harry briefly before he dies, having been mortally wounded by the Chief.[lower-alpha 2] Immediately after this, Gillian receives a call from his estranged wife Jamie, telling him she is being held in the "Kremlin".

Gillian and Metal Gear travel to an abandoned church resembling the Kremlin, where they find Jamie being held captive by a scientist named Elijah Modnar, who explains Gillian's past. He, his father and Jamie were involved in a secret experiment taken under by the Soviet Union over 50 years prior during the Cold War to create Snatchers, which were designed to kill and replace world leaders, giving the Soviets more power. Gillian was a CIA agent spying on the project, who married Jamie and had a child with her, Harry Benson. Gillian and Jamie were placed in a cryogenic sleep when Elijah released Lucifer-Alpha into the atmosphere. The pair were saved by the army, and lost their memories due to the extended period of time they had been frozen. Having become corrupt with power, Elijah reveals that he intends for the Snatchers to wipe out and replace humanity as proof of mankind's follies; he also reveals that Random was an anti-Snatcher created by his late father based on Elijah's appearance and memories, and presents his deactivated body. At this point, Random reactivates and holds Elijah at bay, allowing Gillian and Jamie to escape. Metal Gear activates an orbital weapon, which destroys the Snatcher base, killing Elijah and Random. Having learned of a larger Snatcher factory in Moscow, Gillian prepares to embark on a mission there in the hope of finally destroying the Snatcher menace and rekindling his romance with Jamie.

Development and release

PC-8801 and MSX2

Snatcher was created by Hideo Kojima, working for Konami.[2] Heavily influenced by Blade Runner (1982) and other works of cinema, he wanted to develop a game with a similar style.[4][5] The game was pitched as a "cyberpunk adventure". Kojima found it difficult to explain the meaning of "cyberpunk" to Konami's trademark department over the phone.[6] The game was originally titled Junker, but the name sounded too similar to an existing mahjong game. The title New Order was also considered. Kojima did not like the final name because his previous game, Metal Gear (1987), was also named after an enemy in the game.[6]

Development began between Kojima and character designer Tomiharu Kinoshita, who both treated the project like making a film or anime rather than a game.[7] They expanded to form a small team at Konami, about half the size needed for a typical Famicom game, which allowed them to work closely and quickly.[2] The game is filled with science fiction culture references that skirt copyright laws.[4] Kojima told Kinoshita to make Gillian similar to Katsuhiro Otomo, director of the science fiction film Akira (1988).[2] After a year and a half, Snatcher was only half completed.[4] Originally Kojima planned six chapters, but was told to trim them down to two.[4] The team wanted to create a third chapter, but were already over the allowed development schedule so were forced to abandon it and end the game on a cliffhanger.[8][9] Development took about two to three times longer than the average game.[8] The team never aimed for the game to have a mature atmosphere, but it naturally progressed in that direction.[8]

Originally Snatcher was going to be a PC-8801 exclusive, but it was also developed for the MSX2 at the request of Konami.[10] The PC-8801 version used built-in FM sound while the MSX2 version came with a special cartridge that provided an expanded soundscape beyond the platform's default capabilities and extra RAM, featuring different music track arrangements.[10] Normally, MSX2 games were cheaper at retail than their PC-8801 counterparts, but the expansion cartridge increased the MSX2 version's price.[10] The quantity of music and sound was greater than other games at the time, and required a larger than usual sound team.[11] Because neither platform was capable of accurately synthesizing speech, sound effects were used to represent character dialogue.[8]

In addition to fourth wall breaking dialogue in the game, Kojima wanted to print a secret message and heat-activated scent on the floppy disks that could be noticed after warming them up in the disk drive, but Konami did not approve his idea.[12][13] Snatcher was released for the PC-8801 on November 26, 1988,[14] and the MSX2 in December that year.[15] Two fan translations of the MSX2 version, one in Portuguese and the other in English, were released in 2003 by Fudeba Software.[16]

PC Engine

Players began asking for a home console version soon after release.[8] Because the game was large and required several floppy disks, only CD-ROM systems were considered as opposed to systems that ran ROM cartridges. The PC Engine had the Super CD-ROM² System available so it was chosen to host Snatcher's console port.[8] This port was the first time the development team worked with CD technology.[2]

The team added a third act to this version, a decision they were criticized internally for as others believed the game was already long enough.[8] Using CD technology enabled them to add recorded speech and high quality background music.[8] Artist Satoshi Yoshioka recreated the graphics for this version.[2] Kojima wanted the visuals to appear as "cinematic" as possible, so Yoshioka pulled inspiration from Blade Runner, The Terminator (1984), and Alien (1979) to replicate their Hollywood-style special effects.[2] He used a custom drawing application by Konami to create the character graphics, including the facial expressions during conversations. He found Gillian's expressions to be the most difficult to animate due to the complexities of his characterization.[2]

A demo disc was released ahead of the game's release on August 7, 1992, and was playable at the Tokyo Toy Show in 1992.[17] The full game was released on October 23, 1992[18] and reportedly sold very well for a PC Engine game.[8] This version was released again in Japan for the PlayStation on January 26, 1996,[19] and the Sega Saturn on March 29 that same year.[20]

Sega CD localization

After releasing their first game on the Sega CD, Lethal Enforcers (1992), Konami wanted to bring a more interactive experience to the system for Western players. They considered making a game in full motion video like Night Trap (1992) but thought it may be too difficult, and ultimately decided to localize and port Snatcher.[8] This also gave them an opportunity to improve upon the PC Engine version which they were still not completely satisfied with.[8] They used Roland Sound Space technology for richer music.[5] Although the Sega CD could only display 64 colors simultaneously (compared to the PC Engine's 256), the team used software techniques to increase this to 112 and modified some of the palettes to compromise.[8]

Several scenes were censored or otherwise altered for the Sega CD release.[8] A woman's breasts were covered up, while a 14-year-old girl shown standing naked in a shower was now obscured and her age was changed to 18.[8] Some options that allowed Gillian to engage in behaviors related to sexual harassment were removed or toned down, such as those that allowed him to sniff panties or stare at breasts.[21] Audio in which a robot becomes aroused while watching a pornographic film was cut out entirely.[8] The violence was not altered, except for one scene where a partially dead dog with twitching innards was made completely dead with no twitching.[8] Fearing copyright issues in the United States, the clientele in a bar was changed from Kamen Rider, the Alien, and other characters to Konami characters.[8] Feeling that the third act was too movie-like, Konami added more interactivity through additional forks and choices. Additionally, the player is now graded on how well they solved the mysteries.[8]

The game was translated by Scott Hards, with supervision from Jeremy Blaustein and Konami of Japan.[5][21] The translation took about 2-3 months.[21] Seven voice actors recorded about two and a half hours of dialogue for 26 different characters.[8] With the large amount of text included in the game, the translation was expensive, and Konami felt it was the most difficult part of the porting process.[8] According to Blaustein, Kojima was not involved with the Sega CD port, likely working on Policenauts (1994) at the time.[21]

Snatcher was released in December 1994 in Europe and January 1995 in North America.[22][23] It was a late release for the Sega CD and sold poorly.[3] According to Blaustein, it only sold a couple thousand copies in the United States and was ultimately a commercial failure.[21]

Reception

| Sega CD reviews | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

The PC-8801 and MSX2 versions received positive reviews in Japan and attained a cult following, but were not commercially successful.[8] The PC Engine version also attained a following in Japan in part because of its gore.[28][27] Famicom Tsushin gave it a 33 out of 40, commending its cinematic quality.[29] It was still listed on their "Reader's Best 20" list two years after release.[8] The Sega Saturn version, released several years later, was found to be a faithful port of the PC Engine version by Sega Saturn Magazine.[30]

When Snatcher arrived to the west on the Sega CD, it received praise for its story, cinematic presentation, and mature themes.[27][31][32][25] It was more cinematic and told a more mature story than gamers were familiar with at the time.[2][10][33][34] Mean Machines Sega felt Snatcher was more substantial than other adventure games, calling it "one of the most involved storyboards and backgrounds of any video game".[25] The game's writing was generally lauded,[22][31][32] but VideoGames and Game Players felt the game's juvenile humor sometimes conflicted from its otherwise serious tone.[24][27] A reviewer at GameFan called it "one of the longest, most involving games" he had played in a long time. He wrote: "Never before have I played – nay experienced – a game this moving, dramatic, gore-riddled, MA-17, adult". The magazine praised Konami for retaining most of the mature content.[32]

Mean Machines Sega believed Snatcher's presentation was heightened through the use of CD-ROM technology, which supported the digitized voices and high quality graphics.[25] Some critics praised the English voice acting and writing,[27][32][25] though Next Generation criticized them.[23] The graphics were criticized by Computer and Video Games as "dated" and VideoGames as "generic".[22][27] Other magazines discussed the graphics in more positive light.[31][25][24] GamePro liked the Japanese anime style graphics and felt that combined with the writing, it drew players into the story.[28] They criticized the music however, calling it "old-fashioned for a cyberpunk adventure",[28] while Mean Machines Sega compared it positively to John Carpenter-style incidental themes.[25]

Critics felt the game was slow moving at times, but rewarded patient players.[22][31][28] GamePro wrote that it rewards "patience, persistence, and plodding".[28] Ultimate Future Games felt the game was too linear, and leaned too heavily on the illusion of choice when the story could only be advanced by completing tasks in a certain order.[26] Mean Machines Sega felt the puzzles were challenging and the game was considerably longer and more substantial than Rise of the Dragon (1990), another cyberpunk adventure game.[25] Computer and Video Games felt the gun shooting sections were weak and disappointing.[22]

Retrospective

Snatcher has been called one of the best adventure games[35][36] and best cyberpunk games of all time.[37][38] It has continued to receive praise for its story and presentation.[2][37][33] Waypoint wrote that its narrative and visuals hold up, in contrast to most Sega CD and cyberpunk adventure games.[3] Kotaku called it a "science fiction cornucopia" and liked how the game explored topics of human existence and the fear of machines replacing humans.[2] They felt the game was heavily influenced by science fiction films including Blade Runner, The Terminator, Akira, and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956).[33] Other publications also picked up on these inspirations, especially that from Blade Runner.[35][39][40] Retro Gamer felt it was ironic how the game was more cinematic than games using full motion video.[39] Destructoid enjoyed the plot, but complained about the interface.[40] AllGame wrote that text-based menu driven games like Snatcher can become tedious, but they felt the storyline and graphics made Snatcher worth its time.[35]

Critics have discussed Snatcher as setting the stage for Kojima's later works.[33] 1UP.com felt the game demonstrated his love for film and was "more of a cerebral affair than some of [his] other efforts, but his ingenuity and attention to detail helped make this game especially noteworthy".[41] The game uses themes explored in later Kojima games including jealousy, deception, greed, and international conflict.[5] Game Informer wrote that Snatcher foreshadowed Kojima's use of science fiction to explore philosophy, sex, and the human condition in Metal Gear Solid.[38] Snatcher remains one of Kojima's most renowned games,[39][41] but is often overshadowed by the Metal Gear Solid series.[42][43]

Legacy

Snatcher has obtained a cult following that continues to grow.[3][44][45] It has been an influence on other science fiction works, including Project Itoh's novel Genocidal Organ,[46] and the 2015 adventure game 2064: Read Only Memories.[47] Kojima has expressed interest in reviving Snatcher in some capacity,[48] and has explained he does not have the time to work on the project himself but would welcome another director to lead it.[3][44][43] According to him, such a project has never been feasible from a business perspective,[48] and in 2011, said that a sequel would need to sell over half a million copies to make sense financially.[3][49] The game remains a property of Konami, who has not expressed interest in reviving it, either through a rerelease or sequel.[3][34]

The game's lack of availability on modern platforms has surprised critics,[3][50] especially since it would play well on a Nintendo DS or 3DS, following the footsteps of successful graphic adventures on those platforms like Hotel Dusk and Phoenix Wright.[50][51] The Sega CD version remains the sole release in western territories. Demand has driven up the prices on these copies on the secondary market, making emulation a more reasonable option for most players. Japanese copies are far cheaper but the game's text-based nature makes it unplayable for non-Japanese readers.[3] Fans have experimented with porting the game to other systems. A demo of an early part of the game was made for the Virtual Boy in 2015, complete with stereoscopic 3D effects and PCM music.[52][53][54] Another fan port for the Dreamcast was also in development at one time. The game was to feature a remixed soundtrack and retouched visuals.[34][55][56]

Snatcher was the first translation project for Jeremy Blaustein, who went on to translate Kojima's Metal Gear Solid (1998).[21] Blaustein launched a crowdfunding campaign on Kickstarter for a steampunk adventure game titled Blackmore in 2014.[57][58] The game was to be directed by Blaustein with former Snatcher staff making up other parts of the team.[58] It did not meet its funding goal.[59]

SD Snatcher

Snatcher was remade into a role-playing game called SD Snatcher for the MSX2, released in 1990.[9][33][60] The "SD" stands for "super deformed", referring to the chibi look of the characters. The game plays from a top-down perspective, where the player controls Gillian as he ventures through the environment. When the player encounters an enemy on the field, the game shifts to a first-person battle mode. The player must shoot down enemies using one of many different guns. Different parts of an enemy can be targeted and different weapons have varying abilities and ranges.[9] Outside of key plot points, the game significantly changes the locations explored and events which transpired in the original. This game also concludes the story in a similar manner to the CD-ROM versions of Snatcher.[9] Like the MSX2 version of Snatcher, SD Snatcher shipped with the expanded sound cartridge. It was translated by fans in 1993, making it one of the earliest documented fan translations.[9]

Sdatcher

An episodic radio drama prequel called Sdatcher[lower-alpha 3] was released in 2011 through a collaboration between Kojima and game designer Goichi Suda.[3][62] Suda credited Snatcher, along with works by Yu Suzuki, for ignited his interest in video games.[63] He asked Kojima if he wanted to make a new game together, and the project lead to a radio drama.[64] It was first announced in 2007.[62] The script was written by Suda,[65] and the music was composed by Akira Yamaoka, who worked for Suda in his Grasshopper Manufacture studio and previously worked on the Silent Hill series.[45] Original Snatcher artist Satoshi Yoshioka did promotional illustrations.[45] The first act was released in September with new acts released every other week through November that year.[66] It was distributed for free and later sold on CDs.[67] It was later translated by fans.[68]

Notes

- ↑ Sunacchā (スナッチャー) in Japanese

- ↑ The original version of the game (PC-8801 and MSX2 versions) end at this point, at the end of the second act. The following events take place in the third act which is exclusive to later versions of the game.

- ↑ The title Sdatcher is a pormanteau of "Suda" and "Snatcher".[61]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kalata, Kurt (May 8, 2011). "Snatcher". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on August 17, 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Tieryas, Peter (June 16, 2017). "Snatcher Is Cyberpunk Noir At Its Best". Kotaku. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Diver, Mike (July 14, 2017). "Inside 'Snatcher', Hideo Kojima's Cyberpunk Masterpiece". Waypoint. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Gifford, Kevin (November 4, 2009). "Kojima Reflects on Snatcher, Adventure Games". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Hopper, Ben (February 20, 2001). "Great Games – Snatcher". GameCritics.com. Archived from the original on October 6, 2007.

- 1 2 Gantayat, Anoop (August 13, 2012). "Hideo Kojima: Policenauts Was Originally Known as Beyond". Andriasang. Archived from the original on December 25, 2012.

- ↑ Konami (1989). スナッチャーラインーノーツ. Snatcher (Radio Play CD) liner notes. pp. 3–4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 "EGM's Nob Ogasawara Interviews Mr. Yoshinori "Moai" Sasaki..." (PDF). Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 66. January 1995. p. 176. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kalata, Kurt (May 8, 2011). "SD Snatcher". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "スナッチャーの敵はメタルギア!? コナミのMSXゲーム伝説5:MSX30周年". 週刊アスキー (in Japanese). April 17, 2014. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ↑ Konami (1992). SCCメモリアル ラインーノーツ. SCC Memorial Series: Snatcher Joint Disk (liner notes) (in Japanese). p. 8.

- ↑ Gilbert, Ben (March 16, 2012). "Hideo Kojima recalls Snatcher's heat-activated disk (what?)". Engadget. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ↑ Bonds, Ian (March 30, 2012). "Love Snatcher? This would have made you love it even MORE". destructoid. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ↑ "SNATCHER". Super Soft Magazine Deluxe: A.V.G & R.P.G (in Japanese). Vol. 10. 1988. pp. 3, 54. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ↑ Kojima, Hideo (December 23, 2013). ""SNATCHER"s release in 1988, PC88 was on Nov, MSX2 ver was on Dec". Twitter. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

- ↑ "Snatcher - A Tradução". Amusement Factory. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- ↑ "SNATCHER" (PDF). PC Engine Fan (in Japanese). August 1992. p. 81. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ↑ "スナッチャー [PCエンジン] / ファミ通.com". www.famitsu.com. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ↑ "スナッチャー [PS] / ファミ通.com". www.famitsu.com. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ↑ "スナッチャー [セガサターン] / ファミ通.com". www.famitsu.com. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Interview with Jeremy Blaustein by Chris Barker". Junker HQ. Archived from the original on October 29, 2007. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "CVG Review: Snatcher" (PDF). Computer and Video Games. No. 158. January 1995. pp. 54–56. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 1, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Rating Genesis: Snatcher" (PDF). Next Generation. No. 1. 1995. p. 99. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 1, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Snatcher". Game Players. Vol. 8 no. 1. January 1995.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Mega-CD Review: Snatcher" (PDF). Mean Machines Sega. No. 27. January 1995. pp. 72–74. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 2, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- 1 2 "Role-Playing: Snatcher" (PDF). Ultimate Future Games. No. 2. January 1995. p. 90. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 2, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dulin, Ron (January 1995). "Sega CD: Snatcher" (PDF). VideoGames. p. 69. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Role Player's Realm: Snatcher" (PDF). GamePro. No. 67. February 1995. p. 118. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ↑ "スナッチャーの評価・レビューとブログ [PCエンジン]". Famitsu (202). Archived from the original on October 7, 2018.

- ↑ "スナッチャー" (PDF). セガサターンマガジン (in Japanese). Vol. 6. April 12, 1996. p. 231. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "Review Crew: Snatcher" (PDF). Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 65. December 1994. p. 44. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "Viewpoint: Snatcher". GameFan. Vol. 2 no. 12. December 1994. pp. 26, 46–47.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Plunkett, Luke (September 5, 2011). "Snatcher, Hideo Kojima's Adventure Masterpiece". Kotaku. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Diver, Mike (January 21, 2015). "This Game Deserves an HD Remake More Than Any Other". Waypoint. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Snatcher". AllGame. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Snatcher". Retro Gamer. July 16, 2008. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- 1 2 Bishop, Sam (July 15, 2009). "Blasts from the Past: Classics Updated". IGN. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- 1 2 Gwaltney, Javy (June 15, 2018). "The Top 10 Cyberpunk Games Of All Time". Game Informer. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Top Ten Mega CD Games". Retro Gamer. April 11, 2014. Archived from the original on January 15, 2017. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- 1 2 Burch, Anthony (April 30, 2009). "Snatcher, reconsidered: why you need to play it, but won't". Destructoid. Archived from the original on July 10, 2015.

- 1 2 Chen, David (December 14, 2005). "Retro/Active: Kojima's Productions". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on June 6, 2012.

- ↑ Hinkle, David (July 8, 2009). "Fan recreating Kojima's Snatcher in Crysis Wars". Engadget. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- 1 2 Cavalli, Earnest (March 14, 2014). "Metal Gear creator Kojima talks Snatcher, potential mobile adventures". Engadget. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- 1 2 Haske, Steve (March 15, 2014). "Attention Devs: Hideo Kojima Would Support A "Snatcher" Revival". Complex. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Pereira, Chris (July 7, 2011). "Kojima Details His Suda 51 Collaboration, Sdatcher". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ↑ "小島秀夫監督が"自分の分身のような存在"と評したSF作家,故・伊藤計劃氏とは?「伊藤計劃記録:第弐位相」刊行記念トークショーをレポート". 4Gamer.net (in Japanese). April 25, 2011. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ Madnani, Mikhail (February 28, 2018). "Snatcher Inspired Read Only Memories: Type M Releases on March 6th for iOS and Android, Pre-Order Available Now for Free". TouchArcade. Archived from the original on August 6, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- 1 2 Robinson, Martin (September 27, 2012). "Policenauts, Silent Hill and a Metal Gear JRPG - an audience with Kojima". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ↑ Yin-Poole, Wesley (July 19, 2011). "Kojima on viability of Snatcher sequel". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- 1 2 Diver, Mike (May 5, 2017). "Why Can't We Have a New 'Snatcher' Is Today's Open Thread". Waypoint. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ Fletcher, JC (April 3, 2007). "DS wishlist is an excuse to talk about Snatcher". Engadget. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ↑ Plunkett, Luke (April 19, 2015). "Snatcher, Now On...Virtual Boy?". Kotaku. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ Boatman, Brandon (April 19, 2015). "Fan Ports Snatcher to Virtual Boy". Hardcore Gamer. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ Whitehead, Thomas (April 18, 2015). "Fan Ports Hideo Kojima's Cyberpunk Classic, Snatcher, to the Virtual Boy". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ↑ Hansen, Steve (March 5, 2014). "Homebrewers doing Dreamcast remaster of Kojima's Snatcher". Destructoid. Archived from the original on April 5, 2016. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ↑ Davison, Pete (March 4, 2014). "Homebrew Dev Working on Remixing Kojima's Snatcher for Dreamcast". USgamer.net. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ↑ Prell, Sam (February 12, 2014). "Snatcher devs reunite for steampunk adventure Blackmore". Engadget. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- 1 2 Yin-Poole, Wesley (November 2, 2014). "Ex-Snatcher devs announce Kickstarter for steampunk London adventure Blackmore". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Blackmore: A Steampunk Adventure Game". Kicktraq. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ↑ Fletcher, JC (March 1, 2007). "Virtually Overlooked: SD Snatcher". Engadget. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ↑ Sinclair, Brendan (July 8, 2011). "Kojima, Suda-51 team up for Sdatcher radio drama". GameSpot. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- 1 2 Sato, Yoshi (April 18, 2007). "Suda 51 Reveals Project-S : News from 1UP.com". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on May 17, 2012. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ↑ Gantayat, Anoop (January 23, 2006). "Killer 7 Producer Starts Revolution Project". IGN. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ↑ "[TGS 2011]「メタルギア」キャスト陣と須田剛一さんがゲストとして登場したKONAMIブースの超豪華ラストステージ「Kojima Productions SPECIAL STAGE」をレポート". 4Gamer.net (in Japanese). September 19, 2011. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ IGN Staff (April 18, 2007). "Snatcher Returns". IGN. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ↑ Pereira, Chris (September 2, 2011). "Snatcher Radio Drama's First Act Now Available". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on May 29, 2016.

- ↑ Pereira, Chris (August 8, 2011). "Snatcher Radio Drama Will be Free Initially, Sold on CD Later". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on May 29, 2016.

- ↑ Plunkett, Luke (September 23, 2011). "The Snatcher Radio Drama has Been (Unofficially) Translated". Kotaku. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.