Senescence

Senescence (/sɪˈnɛsəns/) or biological aging is the gradual deterioration of functional characteristics. The word senescence can refer either to cellular senescence or to senescence of the whole organism. Organismal senescence involves an increase in death rates and/or a decrease in fecundity with increasing age, at least in the later part of an organism's life cycle.

Senescence is the inevitable fate of all multicellular organisms with germ-soma separation,[1] but it can be delayed. The discovery, in 1934, that calorie restriction can extend lifespan by 50% in rats, and the existence of species having negligible senescence and potentially immortal species such as Hydra, have motivated research into delaying senescence and thus age-related diseases. Rare human mutations can cause accelerated aging diseases.

Environmental factors may affect aging, for example, overexposure to ultraviolet radiation accelerates skin aging. Different parts of the body may age at different rates. Two organisms of the same species can also age at different rates, making biological aging and chronological aging distinct concepts.

There are a number of hypotheses as to why senescence occurs.

Definition and characteristics

Organismal senescence is the aging of whole organisms. Actuarial senescence can be defined as an increase in mortality and/or a decrease in fecundity with age. The Gompertz–Makeham law of mortality says that that the age-dependent component of the mortality rate increases exponentially with age.

In 2013, a group of scientists defined nine hallmarks of aging that are common between organisms with emphasis on mammals: genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, deregulated nutrient sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, and altered intercellular communication.[2] Aging is characterized by the declining ability to respond to stress, increased homeostatic imbalance, and increased risk of aging-associated diseases including cancer and heart disease. Aging has been defined as "a progressive deterioration of physiological function, an intrinsic age-related process of loss of viability and increase in vulnerability."[3]

The environment induces damage at various levels, e.g. damage to DNA, and damage to tissues and cells by oxygen radicals (widely known as free radicals), and some of this damage is not repaired and thus accumulates with time. Cloning from somatic cells rather than germ cells may begin life with a higher initial load of damage. Dolly the sheep died young from a contagious lung disease, but data on an entire population of cloned individuals would be necessary to measure mortality rates and quantify aging.

The evolutionary theorist George Williams wrote, "It is remarkable that after a seemingly miraculous feat of morphogenesis, a complex metazoan should be unable to perform the much simpler task of merely maintaining what is already formed."[4]

Variation among species

Differences rates of aging, i.e. different speeds with which mortality increases with age, correspond to different maximum life span among species. For example, a mouse is elderly at 3 years while a human is elderly at 80 years.[5]

Almost all organisms senesce, including bacteria which have asymmetries between "mother" and "daughter" cells upon cell division, with the mother cell experiencing aging, while the daughter is rejuvenated. Senescence has been so far undetectable in a handful of species (negligible senescence), such as those in the genus Hydra. Planarian flatworms have "apparently limitless telomere regenerative capacity fueled by a population of highly proliferative adult stem cells."[6] These organisms may be biologically immortal, meaning not that they do not die, but that their death rate does not increase with age. Some species exhibit "negative senescence", in which fecundity increases and/or mortality falls with age, due to the advantages of increased body size with age.[7]

Evolutionary theories of aging

Mutation accumulation

Natural selection can support lethal and harmful alleles, if their effects are felt after reproduction. The geneticist J. B. S. Haldane wondered why the dominant mutation that causes Huntington's disease remained in the population, and why natural selection had not eliminated it. The onset of this neurological disease is (on average) at age 45 and is invariably fatal within 10–20 years. Haldane assumed that, in human prehistory, few survived until age 45. Since few were alive at older ages and their contribution to the next generation was therefore small relative to the large cohorts of younger age groups, the force of selection against such late-acting deleterious mutations was correspondingly small. Therefore, a genetic load of late-acting deleterious mutations could be substantial at mutation-selection balance. This concept came to be known as the selection shadow.[8]

Peter Medawar formalised this observation in his mutation accumulation theory of aging.[9][10] "The force of natural selection weakens with increasing age—even in a theoretically immortal population, provided only that it is exposed to real hazards of mortality. If a genetic disaster... happens late enough in individual life, its consequences may be completely unimportant". The 'real hazards of mortality' such as predation, disease, and accidents, are known 'extrinsic mortality', and mean that even a population with negligible senescence will have fewer individuals alive in older age groups.

Antagonistic pleiotropy

Another evolutionary theory of aging was proposed by George C. Williams[11] and involves antagonistic pleiotropy. A single gene may affect multiple traits. Some traits that increase fitness early in life may also have negative effects later in life. But, because many more individuals are alive at young ages than at old ages, even small positive effects early can be strongly selected for, and large negative effects later may be very weakly selected against. Williams suggested the following example: Perhaps a gene codes for calcium deposition in bones, which promotes juvenile survival and will therefore be favored by natural selection; however, this same gene promotes calcium deposition in the arteries, causing negative atherosclerotic effects in old age. Thus, harmful biological changes in old age may result from selection for pleiotropic genes that are beneficial early in life but harmful later on. In this case, selection pressure is relatively high when Fisher's reproductive value is high and relatively low when Fisher's reproductive value is low.

An important example of antagonistic pleiotropy is the trade-off between investing resources in reproduction, rather than maintenance of the body (the "Disposable Soma" theory[12]).

Adaptive aging

Programmed theories of aging posit that aging is adaptive, normally invoking selection for evolvability or group selection.

The reproductive-cell cycle theory suggests that aging is regulated by changes in hormonal signaling over the lifespan.[13]

Cellular senescence

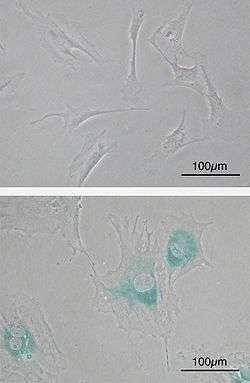

(upper) Primary mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (MEFs) before senescence. Spindle-shaped. (lower) MEFs became senescent after passages. Cells grow larger, flatten shape and expressed senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SABG, blue areas), a marker of cellular senescence.

Cells accumulate damage over time, but this may be counterbalanced by natural selection to remove damaged cells. In particular DNA damage, e.g. due to reactive oxygen species, leads to the accumulation of harmful somatic mutations.[14]

In most multicellular species, somatic cells eventually experience replicative senescence and are unable to divide. This can prevent highly mutated cells from becoming cancerous. In culture, fibroblasts can reach a maximum of 50 cell divisions; this maximum is known as the Hayflick limit.[15] Replicative senescence is the result of telomere shortening that ultimately triggers a DNA damage response. Cells can also be induced to senesce via DNA damage in response to elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS), activation of oncogenes and cell-cell fusion, independent of telomere length.

The cellular senescence theory of aging posits that organismal aging is a consequence of the accumulation of less physiological useful senescent cells. In agreement with this, the experimental elimination of senescent cells from transgenic progeroid mice[16] and non-progeroid, naturally-aged mice[17][18][19] led to greater resistance against aging-associated diseases. Ectopic expression of the embryonic transcription factor, NANOG, is shown to reverse senescence and restore the proliferation and differentiation potential of senescent stem cells.[20][21][22][23][24]

Senescent cells can undergo conversion to an immunogenic phenotype that enables them to be eliminated by the immune system.[25] This phenotype consists of a pro-inflammatory secretome, the up-regulation of immune ligands, a pro-survival response, promiscuous gene expression (pGE) and stain positive for senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity.[26] The nucleus of senescent cells is characterized by senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF) and DNA segments with chromatin alterations reinforcing senescence (DNA-SCARS).[27] Senescent cells affect tumour suppression, wound healing and possibly embryonic/placental development and a pathological role in age-related diseases.[28]

In many organisms, there is asymmetric cell division, e.g. a stem cell dividing to produce one stem cell and one non-stem cell. The cellular debris that cells accumulate is not evenly divided between the new cells when they divide. Instead more of the damage is passed to one of the cells, leaving the other cell rejuvenated.[29] One lineage then undergoes cellular senescence faster than the other.

Cancer cells avoid replicative senescence to become immortal. In about 85% of tumors, this evasion of cellular senescence is the result of up-activation of their telomerase genes.[30]

Cancer versus cellular senescence tradeoff theory of aging

Senescent cells within a multicellular organism can be purged by competition between cells, but this increases the risk of cancer. This leads to an inescapable dilemma between two possibilities - the accumulation of physiologically useless senescent cells, and cancer - both of which lead to increasing rates of mortality with age.[1]

Chemical damage

One of the earliest aging theories was the Rate of Living Hypothesis described by Raymond Pearl in 1928[31] (based on earlier work by Max Rubner), which states that fast basal metabolic rate corresponds to short maximum life span.

While there may be some validity to the idea that for various types of specific damage detailed below that are by-products of metabolism, all other things being equal, a fast metabolism may reduce lifespan, in general this theory does not adequately explain the differences in lifespan either within, or between, species. Calorically restricted animals process as much, or more, calories per gram of body mass, as their ad libitum fed counterparts, yet exhibit substantially longer lifespans. Similarly, metabolic rate is a poor predictor of lifespan for birds, bats and other species that, it is presumed, have reduced mortality from predation, and therefore have evolved long lifespans even in the presence of very high metabolic rates.[32] In a 2007 analysis it was shown that, when modern statistical methods for correcting for the effects of body size and phylogeny are employed, metabolic rate does not correlate with longevity in mammals or birds.[33] (For a critique of the Rate of Living Hypothesis see Living fast, dying when?[34])

With respect to specific types of chemical damage caused by metabolism, it is suggested that damage to long-lived biopolymers, such as structural proteins or DNA, caused by ubiquitous chemical agents in the body such as oxygen and sugars, are in part responsible for aging. The damage can include breakage of biopolymer chains, cross-linking of biopolymers, or chemical attachment of unnatural substituents (haptens) to biopolymers.

Under normal aerobic conditions, approximately 4% of the oxygen metabolized by mitochondria is converted to superoxide ion, which can subsequently be converted to hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical and eventually other reactive species including other peroxides and singlet oxygen, which can, in turn, generate free radicals capable of damaging structural proteins and DNA. Certain metal ions found in the body, such as copper and iron, may participate in the process. (In Wilson's disease, a hereditary defect that causes the body to retain copper, some of the symptoms resemble accelerated senescence.) These processes termed oxidative stress are linked to the potential benefits of dietary polyphenol antioxidants, for example in coffee,[35] red wine and tea.[36]

Sugars such as glucose and fructose can react with certain amino acids such as lysine and arginine and certain DNA bases such as guanine to produce sugar adducts, in a process called glycation. These adducts can further rearrange to form reactive species, which can then cross-link the structural proteins or DNA to similar biopolymers or other biomolecules such as non-structural proteins. People with diabetes, who have elevated blood sugar, develop senescence-associated disorders much earlier than the general population, but can delay such disorders by rigorous control of their blood sugar levels. There is evidence that sugar damage is linked to oxidant damage in a process termed glycoxidation.

Free radicals can damage proteins, lipids or DNA. Glycation mainly damages proteins. Damaged proteins and lipids accumulate in lysosomes as lipofuscin. Chemical damage to structural proteins can lead to loss of function; for example, damage to collagen of blood vessel walls can lead to vessel-wall stiffness and, thus, hypertension, and vessel wall thickening and reactive tissue formation (atherosclerosis); similar processes in the kidney can lead to renal failure. Damage to enzymes reduces cellular functionality. Lipid peroxidation of the inner mitochondrial membrane reduces the electric potential and the ability to generate energy. It is probably no accident that nearly all of the so-called "accelerated aging diseases" are due to defective DNA repair enzymes.

It is believed that the impact of alcohol on aging can be partly explained by alcohol's activation of the HPA axis, which stimulates glucocorticoid secretion, long-term exposure to which produces symptoms of aging.[37]

Biomarkers of aging

If different individuals age at different rates, then fecundity, mortality, and functional capacity might be better predicted by biomarkers than by chronological age.[38] However, graying of hair,[39] skin wrinkles and other common changes seen with aging are not better indicators of future functionality than chronological age. Biogerontologists have continued efforts to find and validate biomarkers of aging, but success thus far has been limited. Levels of CD4 and CD8 memory T cells and naive T cells have been used to give good predictions of the expected lifespan of middle-aged mice.[40]

There is interest in an epigenetic clock as a biomarker of aging, based on its ability to predict human chronological age.[41] Basic blood biochemistry and cell counts can also be used to accurately predict the chronological age.[42] It is also possible to predict the human chronological age using the transcriptomic aging clocks.[43]

Genetic determinants of aging

A number of genetic components of aging have been identified using model organisms, ranging from the simple budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae to worms such as Caenorhabditis elegans and fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster). Study of these organisms has revealed the presence of at least two conserved aging pathways.

Gene expression is imperfectly controlled, and it is possible that random fluctuations in the expression levels of many genes contribute to the aging process as suggested by a study of such genes in yeast.[44] Individual cells, which are genetically identical, nonetheless can have substantially different responses to outside stimuli, and markedly different lifespans, indicating the epigenetic factors play an important role in gene expression and aging as well as genetic factors.

A set of rare hereditary (genetic) disorders, each called progeria, has been known for some time. Sufferers exhibit symptoms resembling accelerated aging, including wrinkled skin. The cause of Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome was reported in the journal Nature in May 2003.[45] This report suggests that DNA damage, not oxidative stress, is the cause of this form of accelerated aging.

See also

- Ageing

- Aging brain

- Aging-associated diseases

- Anti-aging medicine

- Anti-aging movement

- DNA repair

- Free radicals

- Genetics of aging

- Geriatrics

- Gerontology

- Homeostatic capacity

- Immortality

- Indefinite lifespan

- Life extension

- Mitohormesis

- Old age

- Oxidative stress

- Phenoptosis

- Plant senescence

- Programmed cell death

- Regenerative medicine

- Rejuvenation

- SAGE KE

- Stem cell theory of aging

- Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence (SENS)

- Sub-lethal damage

- Timeline of senescence research

- Transgenerational design

References

- 1 2 Nelson, Paul; Masel, Joanna (5 December 2017). "Intercellular competition and the inevitability of multicellular aging". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (49): 12982–12987. doi:10.1073/pnas.1618854114. PMC 5724245. PMID 29087299.

- ↑ Lopez-Otin, C; et al. (2013). "The hallmarks of aging". Cell. 153 (6): 1194–217. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. PMC 3836174. PMID 23746838.

- ↑ "Aging and Gerontology Glossary". Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ↑ Williams, G.C. (1957). "Pleiotropy, natural selection, and the evolution of senescence". Evolution. 11 (4): 398–411. doi:10.2307/2406060. JSTOR 2406060.

- ↑ Austad, S (2009). "Comparative Biology of Aging". J Gerontol a Biol Sci Med Sci. 64 (2): 199–201. doi:10.1093/gerona/gln060. PMC 2655036. PMID 19223603.

- ↑ Thomas C. J. Tan; Ruman Rahman; Farah Jaber-Hijazi; Daniel A. Felix; Chen Chen; Edward J. Louis & Aziz Aboobaker (February 2012). "Telomere maintenance and telomerase activity are differentially regulated in asexual and sexual worms". PNAS. 109 (9): 4209–4214. doi:10.1073/pnas.1118885109. PMC 3306686. PMID 22371573.

- ↑ W. Vaupel, James; Baudisch, Annette; Dölling, Martin; A. Roach, Deborah; Gampe, Jutta (June 2004). "The case for negative senescence". Theoretical Population Biology. 65 (4): 339–351. doi:10.1016/j.tpb.2003.12.003. PMID 15136009.

- ↑ Fabian, Daniel; Flatt, Thomas (2011). "The Evolution of Aging". Scitable. Nature Publishing Group. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ↑ Medawar PB (1946). "Old age and natural death". Modern Quarterly. 1: 30–56.

- ↑ Medawar, Peter B. (1952). An Unsolved Problem of Biology. London: H. K. Lewis.

- ↑ Williams, George C. (December 1957). "Pleiotropy, Natural Selection, and the Evolution of Senescence" (PDF). Evolution. 11 (4): 398–411. doi:10.2307/2406060. JSTOR 2406060.

- ↑ Kirkwood TB (November 1977). "Evolution of ageing". Nature. 270 (5635): 301–4. doi:10.1038/270301a0. PMID 593350.

- ↑ Bowen RL; Atwood CS (2011). "The reproductive-cell cycle theory of aging: an update". Experimental Gerontology. 46 (2): 100–7. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2010.09.007. PMID 20851172.

- ↑ Bernstein, H; Payne, CM; Bernstein, C; Garewal, H; Dvorak, K (2008). "Cancer and aging as consequences of un-repaired DNA damage.". In Kimura, Honoka; Suzuki, Aoi. New Research on DNA Damage. Nova Science Publishers. pp. 1–47. ISBN 978-1604565812.

- ↑ Hayflick L; Moorhead PS (December 1961). "The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains". Exp. Cell Res. 25 (3): 585–621. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6. PMID 13905658.

- ↑ Baker, D.; Wijshake, T.; Tchkonia, T.; LeBrasseur, N.; Childs, B.; van de Sluis, B.; Kirkland, J.; van Deursen, J. (10 November 2011). "Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders". Nature. 479 (7372): 232–6. doi:10.1038/nature10600. PMC 3468323. PMID 22048312.

- ↑ Xu, M; Palmer, AK; Ding, H; Weivoda, MM; Pirtskhalava, T; White, TA; Sepe, A; Johnson, KO; Stout, MB; Giorgadze, N; Jensen, MD; LeBrasseur, NK; Tchkonia, T; Kirkland, JL (2015). "Targeting senescent cells enhances adipogenesis and metabolic function in old age". eLife. 4: e12997. doi:10.7554/eLife.12997. PMC 4758946. PMID 26687007.

- ↑ Quick, Darren (February 3, 2016). "Clearing out damaged cells in mice extends lifespan by up to 35 percent". www.gizmag.com. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ↑ Regalado, Antonio (February 3, 2016). "In New Anti-Aging Strategy, Clearing Out Old Cells Increases Life Span of Mice by 25 Percent". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ↑ Shahini A, Choudhury D, Asmani M, Zhao R, Lei P, Andreadis S (Jan 2018). "NANOG restores the impaired myogenic differentiation potential of skeletal myoblasts after multiple population doublings". Stem Cell Research. 26: 55–66. doi:10.1016/j.scr.2017.11.018. PMID 29245050.

- ↑ Shahini A, Mistriotis P, Asmani M, Zhao R, Andreadis S (Jun 2017). "NANOG Restores Contractility of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Senescent Microtissues". Tissue Eng Part A. 23 (11–12): 535–545. doi:10.1089/ten.TEA.2016.0494. PMC 5467120. PMID 28125933.

- ↑ Mistriotis P, Bajpai V, Wang X, Rong N, Shahini A, Asmani M, Liang M, Wang J, Lei P, Liu S, Zhao R, Andreadis S (Jan 2017). "NANOG Reverses the Myogenic Differentiation Potential of Senescent Stem Cells by Restoring ACTIN Filamentous Organization and SRF-Dependent Gene Expression". Stem Cells. 35 (1): 207–221. doi:10.1002/stem.2452. PMID 27350449.

- ↑ Han J, Mistriotis P, Lei P, Wang D, Liu S, Zhao R, Andreadis S (Dec 2012). "Nanog Reverses the Effects of Organismal Aging on Mesenchymal Stem Cell Proliferation and Myogenic Differentiation Potential". Stem Cells. 30 (12): 2746–2759. doi:10.1002/stem.1223. PMC 3508087. PMID 22949105.

- ↑ Munst B, Thier M, Winnemoller D, Helfen M, Thummer R, Edenhofer F (Jan 2016). "Nanog induces suppression of senescence through downregulation of p27KIP1 expression". Journal of Cell Science. 129 (5): 912–20. doi:10.1242/jcs.167932. PMC 4813312. PMID 26795560.

- ↑ Burton; Faragher (2015). "Cellular senescence: from growth arrest to immunogenic conversion". AGE. 37 (2): 27. doi:10.1007/s11357-015-9764-2. PMC 4365077. PMID 25787341.

- ↑ Campisi, Judith (February 2013). "Aging, Cellular Senescence, and Cancer". Annual Review of Physiology. 75: 685–705. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183653. PMC 4166529. PMID 23140366.

- ↑ Rodier, F.; Campisi, J. (14 February 2011). "Four faces of cellular senescence". The Journal of Cell Biology. 192 (4): 547–556. doi:10.1083/jcb.201009094. PMC 3044123. PMID 21321098.

- ↑ Burton, Dominick G. A.; Krizhanovsky, Valery (31 July 2014). "Physiological and pathological consequences of cellular senescence". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 71 (22): 4373–4386. doi:10.1007/s00018-014-1691-3. PMC 4207941. PMID 25080110.

- ↑ Stephens C (April 2005). "Senescence: even bacteria get old". Curr. Biol. 15 (8): R308–10. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.04.006. PMID 15854899.

- ↑ Hanahan D; Weinberg RA (January 2000). "The hallmarks of cancer". Cell. 100 (1): 57–70. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81683-9. PMID 10647931.

- ↑ Pearl, Raymond (1928). The Rate of Living, Being an Account of Some Experimental Studies on the Biology of Life Duration. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- ↑ Brunet-Rossinni AK; Austad SN (2004). "Ageing studies on bats: a review". Biogerontology. 5 (4): 211–22. doi:10.1023/B:BGEN.0000038022.65024.d8. PMID 15314271.

- ↑ de Magalhães JP; Costa J; Church GM (1 February 2007). "An Analysis of the Relationship Between Metabolism, Developmental Schedules, and Longevity Using Phylogenetic Independent Contrasts". The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 62 (2): 149–60. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.596.2815. doi:10.1093/gerona/62.2.149. PMC 2288695. PMID 17339640. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014.

- ↑ Speakman JR; Selman C; McLaren JS; Harper EJ (1 June 2002). "Living fast, dying when? The link between aging and energetics". The Journal of Nutrition. 132 (6 Suppl 2): 1583S–97S. doi:10.1093/jn/132.6.1583S. PMID 12042467.

- ↑ Freedman ND; Park Y; Abnet CC; Hollenbeck AR; Sinha R (May 2012). "Association of coffee drinking with total and cause-specific mortality". N. Engl. J. Med. 366 (20): 1891–904. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1112010. PMC 3439152. PMID 22591295.

- ↑ Yang Y; Chan SW; Hu M; Walden R; Tomlinson B (2011). "Effects of some common food constituents on cardiovascular disease". ISRN Cardiol. 2011: 1–16. doi:10.5402/2011/397136. PMC 3262529. PMID 22347642.

- ↑ Spencer RL; Hutchison KE (1999). "Alcohol, aging, and the stress response" (PDF). Alcohol Research & Health. 23 (4): 272–83. PMID 10890824.

- ↑ George T. Baker, III and Richard L. Sprott (1988). "Biomarkers of aging". Experimental Gerontology. 23 (4–5): 223–239. doi:10.1016/0531-5565(88)90025-3. PMID 3058488.

- ↑ Van Neste D, Tobin DJ (2004). "Hair cycle and hair pigmentation: dynamic interactions and changes associated with aging". MICRON. 35 (3): 193–200. doi:10.1016/j.micron.2003.11.006. PMID 15036274.

- ↑ Miller RA (2001). "Biomarkers of aging: prediction of longevity by using age-sensitive T-cell subset determinations in a middle-aged, genetically heterogeneous mouse population". Journals of Gerontology. 56 (4): B180–B186. doi:10.1093/gerona/56.4.b180. PMID 11283189.

- ↑ Horvath S (2013). "DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types". Genome Biology. 14 (10): R115. doi:10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r115. PMC 4015143. PMID 24138928.

- ↑ Zhavoronkov A (2016). "Deep biomarkers of human aging: Application of deep neural networks to biomarker development". Aging. 8 (5): 1021–33. doi:10.18632/aging.100968. PMC 4931851. PMID 27191382.

- ↑ Peters M (2015). "The transcriptional landscape of age in human peripheral blood". Nature Communications. 6: 8570. doi:10.1038/ncomms9570. PMC 4639797. PMID 26490707.

- ↑ Ryley J; Pereira-Smith OM (2006). "Microfluidics device for single cell gene expression analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Yeast. 23 (14–15): 1065–73. doi:10.1002/yea.1412. PMID 17083143.

- ↑ Mounkes LC; Kozlov S (2003). "A progeroid syndrome in mice is caused by defects in A-type lamins" (PDF). Nature. 423 (6937): 298–301. doi:10.1038/nature01631. PMID 12748643.

External links

| Look up senescence in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Senescence. |

- Senescence at Curlie (based on DMOZ)

- Jones, Owen R.; Scheuerlein, Alexander; Salguero-Gómez, Roberto; Camarda, Carlo Giovanni; Schaible, Ralf; Casper, Brenda B.; Dahlgren, Johan P.; Ehrlén, Johan; García, María B.; Menges, Eric S.; Quintana-Ascencio, Pedro F.; Caswell, Hal; Baudisch, Annette; Vaupel, James W. (2013). "Diversity of ageing across the tree of life". Nature. 505 (7482): 169–173. doi:10.1038/nature12789. hdl:10161/14700. PMC 4157354. PMID 24317695. Lay summary – National Geographic (8 December 2013).