Cellular senescence

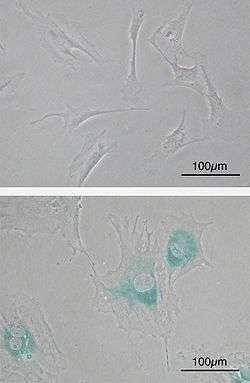

(Lower) MEFs became senescent after passages. Cells grow larger, flatten shape and expressed senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SABG, blue areas), a marker of cellular senescence.

Cellular senescence is one phenomenon by which normal cells cease to divide. In their seminal experiments from the early 1960's, Leonard Hayflick and Paul Moorhead found out that normal human fetal fibroblasts in culture reach a maximum of approximately 50 cell population doublings before becoming senescent.[1][2][3] This phenomenon is known as "replicative senescence", or the Hayflick limit. Hayflick's discovery that normal cells are mortal overturned a 60-year-old dogma in cell biology that maintained that all cultured cells are immortal. Hayflick found that the only immortal cultured cells are cancer cells.[4]

Cellular mechanisms

Mechanistically, replicative senescence is triggered by a DNA damage response which results from the shortening of telomeres during each cellular division process. Cells can also be induced to senesce independent of the number of cellular divisions via DNA damage in response to elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS), activation of oncogenes and cell-cell fusion. The number of senescent cells in tissues rises substantially during normal aging.[5]

Although senescent cells can no longer replicate, they remain metabolically active and commonly adopt an immunogenic phenotype consisting of a pro-inflammatory secretome, the up-regulation of immune ligands, a pro-survival response, promiscuous gene expression (pGE) and stain positive for senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity.[6] Senescence-associated beta-galactosidase, along with p16Ink4A, is regarded to be a biomarker of cellular senescence. This results in false positives for maturing tissue macrophages and senescence-associated beta-galactosidase as well as for T-cells p16Ink4A.[5]

The DNA damage response (DDR) arrests cell cycle progression until damages, such as double-strand breaks (DSBs), are repaired. Senescent cells display persistent DDR foci that appear to be resistant to endogenous DNA repair activities. Such senescent cells in culture and tissues from aged mammals retain true DSBs associated with DDR markers.[7] It has been proposed that retained DSBs are major drivers of the aging process[8] (see DNA damage theory of aging).

Role of telomeres

Lately, the role of telomeres in cellular senescence has aroused general interest, especially with a view to the possible genetically adverse effects of cloning. The successive shortening of the chromosomal telomeres with each cell cycle is also believed to limit the number of divisions of the cell, thus contributing to aging. There have, on the other hand, also been reports that cloning could alter the shortening of telomeres. Some cells do not age and are, therefore, described as being "biologically immortal". It is theorized by some that when it is discovered exactly what allows these cells, whether it be the result of telomere lengthening or not, to divide without limit that it will be possible to genetically alter other cells to have the same capability.

The length of the telomere strand has senescent effects; telomere shortening activates extensive alterations in alternative RNA splicing that produce senescent toxins such as progerin, which degrades the tissue and makes it more prone to failure.[9]

Characteristics of senescent cells

A Senescence Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) consisting of inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and proteases is another characteristic feature of senescent cells.[10] SASP is associated with many age-related diseases, including type 2 diabetes and atherosclerosis.[5] This has motivated researchers to develop senolytic drugs to kill and/or eliminate senescent cells in an effort to improve health in the elderly.[5] Whether or not this approach will prove effective is debatable.

The nucleus of senescent cells is characterized by senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF) and DNA segments with chromatin alterations reinforcing senescence (DNA-SCARS).[11] Senescent cells affect tumour suppression, wound healing and possibly embryonic/placental development and a pathological role in age-related diseases.[12]

Organisms lacking senescence

Cellular senescence is not observed in some organisms, including perennial plants, sponges, corals, and lobsters. In those species where cellular senescence is observed, cells eventually become post-mitotic when they can no longer replicate themselves through the process of cellular mitosis; i.e., cells experience replicative senescence. How and why some cells become post-mitotic in some species has been the subject of much research and speculation, but it has been suggested that cellular senescence evolved as a way to prevent the onset and spread of cancer. Somatic cells that have divided many times will have accumulated DNA mutations and would therefore be in danger of becoming cancerous if cell division continued. As such, it is becoming apparent that senescent cells undergo conversion to an immunogenic phenotype that enables them to be eliminated by the immune system.[13]

See also

References

- ↑ Collado, M; Blasco, MA; Serrano, M (27 July 2007). "Cellular senescence in cancer and aging". Cell. 130 (2): 223–233. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.003.

- ↑ Hayat, M (2014). Tumor dormancy, quiescence, and senescence, Volume 2: Aging, cancer, and noncancer pathologies. Springer. p. 188.

- ↑ Tollefsbol, T (2010). Epigenetics of Aging. Springer. p. 227. ISBN 978-1-4419-0638-0.

- ↑ Shay, JW; Wright, WE (October 2000). "Hayflick, his limit, and cellular ageing". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 1 (1): 72–6. doi:10.1038/35036093. PMID 11413492.

- 1 2 3 4 Childs BG, Durik M, Baker DJ, van Deursen JM (2015). "Cellular senescence in aging and age-related disease: from mechanisms to therapy". Nature Medicine. 21 (12): 1424–1435. doi:10.1038/nm.4000. PMC 4748967. PMID 26646499.

- ↑ Campisi, Judith (February 2013). "Aging, Cellular Senescence, and Cancer". Annual Review of Physiology. 75: 685–705. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183653. PMC 4166529. PMID 23140366.

- ↑ Galbiati A, Beauséjour C, d'Adda di Fagagna F (2017). "A novel single-cell method provides direct evidence of persistent DNA damage in senescent cells and aged mammalian tissues". Aging Cell. 16 (2): 422–427. doi:10.1111/acel.12573. PMC 5334542. PMID 28124509.

- ↑ White RR, Vijg J (2016). "Do DNA Double-Strand Breaks Drive Aging?". Mol. Cell. 63 (5): 729–38. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2016.08.004. PMC 5012315. PMID 27588601.

- ↑ Collins FS, et al. (13 June 2011). "Progerin and telomere dysfunction collaborate to trigger cellular senescence in normal human fibroblasts". J Clin Invest. 121 (7): 2833–44. doi:10.1172/JCI43578. PMC 3223819. PMID 21670498.

- ↑ Malaquin N, Martinez A, Rodier F (2016). "Keeping the senescence secretome under control: Molecular reins on the senescence-associated secretory phenotype". EXPERIMENTAL GERONTOLOGY. 82: 39–49. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2016.05.010. PMID 27235851.

- ↑ Rodier, F.; Campisi, J. (14 February 2011). "Four faces of cellular senescence". The Journal of Cell Biology. 192 (4): 547–556. doi:10.1083/jcb.201009094. PMC 3044123. PMID 21321098.

- ↑ Burton, Dominick G. A.; Krizhanovsky, Valery (31 July 2014). "Physiological and pathological consequences of cellular senescence". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 71 (22): 4373–4386. doi:10.1007/s00018-014-1691-3. PMC 4207941. PMID 25080110.

- ↑ Burton; Faragher (2015). "Cellular senescence: from growth arrest to immunogenic conversion". AGE. 37. doi:10.1007/s11357-015-9764-2. PMC 4365077. PMID 25787341.

Further reading

- Hayflick L, Moorhead PS (1961). "The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains". Experimental Cell Research. 25 (3): 585–621. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6. PMID 13905658.

- Hayflick L. (1965). "The limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains". Experimental Cell Research. 37 (3): 614–636. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(65)90211-9. PMID 14315085.

External links