Balkan Mountains

| Balkan Mountains | |

|---|---|

| Stara Planina, Стара планина | |

A view from Kom Peak in western Bulgaria. | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Botev Peak |

| Elevation | 2,376 m (7,795 ft) |

| Coordinates | 42°43′00″N 24°55′04″E / 42.71667°N 24.91778°E |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 530 km (330 mi) west-east |

| Width | 15–50 km (9.3–31.1 mi) north-south |

| Area | 11,596 km2 (4,477 sq mi) |

| Geography | |

| |

| Countries | Bulgaria and Serbia |

| Range coordinates | 43°15′N 25°0′E / 43.250°N 25.000°ECoordinates: 43°15′N 25°0′E / 43.250°N 25.000°E |

| Geology | |

| Type of rock | granite, gneiss, limestone |

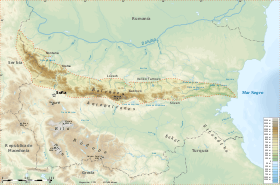

The Balkan mountain range (Bulgarian and Serbian Cyrillic: Стара планина, Serbian Latin: Stara planina, "Old Mountain"; Bulgarian pronunciation: [ˈstarɐ pɫɐniˈna]; Serbian pronunciation: [stâːraː planǐna])[1] is a mountain range in the eastern part of the Balkan Peninsula. The Balkan range runs 560 km from the Vrashka Chuka Peak on the border between Bulgaria and Serbia eastward through central Bulgaria to Cape Emine on the Black Sea. The highest peaks of the Balkan Mountains are in central Bulgaria. The highest peak is Botev at 2,376 m, which makes the mountain range the third highest in the country, after Rila and Pirin. The mountains are the source of the name of the Balkan Peninsula.

The mountain range forms the watershed between the Black Sea and Aegean Sea catchment areas, with the exception of an area in west, where it is crossed by the spectacular Iskar Gorge. The karst relief determines the large number of caves, including Magura, featuring the most important and extended European post-Palaeolithic cave painting, Ledenika, Saeva dupka, Bacho Kiro, etc. The most notable rock formation are the Belogradchik Rocks in the west.

There are several important protected areas: Central Balkan National Park, Vrachanski Balkan Nature Park, Bulgarka Nature Park and Sinite Kamani Nature Park, as well as a number of nature reserves. The Balkan Mountains are remarkable for their flora and fauna. Edelweiss grows there in the region of Kozyata stena. Some of the most striking landscapes are included in the Central Balkan National Park with steep cliffs, the highest waterfalls in the Balkan Peninsula and lush vegetation. There are a number of important nature reserves such as Chuprene, Kozyata stena and others. Most of Europe's large mammals inhabit the area including the brown bear, wolf, boar, chamois and deer.

The Balkan Mountains played an enormous role in the history of Bulgaria since its foundation in 681 AD, and in the development of the Bulgarian nation and people.

Etymology

It is believed the name was brought to the region in the 7th century by Bulgars who applied it to the area, as a part of the First Bulgarian Empire. In Bulgarian, the word balkan (балкан) means "mountain".[2] It may have derived from the Persian bālkāneh or bālākhāna, meaning "high, above, or proud house."[3] The name is still preserved in Central Asia with the Balkan Daglary (Balkan Mountains)[4] and the Balkan Province of Turkmenistan. In Turkish balkan means "a chain of wooded mountains"[5][6]

In Antiquity and the Middle Ages the mountains were known by their Thracian[1] name: the Haemus Mons. Scholars consider that the name Haemus (Αἷμος) is derived from a Thracian word *saimon, 'mountain ridge'.[7] The name of the place where the range meets the Black Sea, Cape Emine, is derived from Aemon. A folk etymology holds that 'Haemus' derives from the Greek word "haema" (αἵμα) meaning 'blood', and is based on Greek mythology. During a fight between Zeus and the monster/titan Typhon, Zeus injured Typhon with thunder; and Typhon's blood fell on the mountains, which were then named for this battle.[8]

Other names used to refer to the mountains in different time periods include Aemon, Haemimons, Hem, Emus, the Slavonic Matorni gori and the Turkish Kodzhabalkan.[9]

Geography

Geologically, the Balkan Mountains are a "young" part of the Alp-Himalayan chain that stretches across most of Europe and Asia. It can be divided into two parts: the main Balkan Chain and the Pre-Balkans (Fore-Balkan) to the north, which intrude slightly into the Danubian Plain. To the south, the mountains border the Sub-Balkan valleys - a row of 11 valleys running from the Bulgarian border with Serbia east to the Black Sea, separating the Balkan mountains from a chain of other mountains known as Srednogorie which includes Vitosha and Sredna Gora.

The range consists of around 30 distinct mountains. Within Bulgaria the Balkan Mountains can be divided into three sections:

- The Western Balkan Mountains extend from Vrashka Chuka at the border with Serbia to the Pass of Arabakonak with a total length of 190 kilometres (120 mi). The highest peak is Midžor at 2,169 metres (7,116 ft).

- The Central Balkan Mountains run from Arabakonak to the Vratnik Pass with a length of 207 kilometres (129 mi). Botev Peak, the highest mountain in the Balkan range at 2,376 metres (7,795 ft), is located in this section.

- The Eastern Balkan Mountains extend from the Vratnik Pass to Cape Emine with a length of 160 kilometres (99 mi). The highest peak is Balgarka at 1,181 metres (3,875 ft). The eastern Balkan Mountains form the lowest part of the range.

| Section | Area, km2 |

% | Average altitude, m | 0 – 200 m, km2 | % | 200 – 600 m, km2 | % | 600 – 1000 m, km2 | % | 1000 – 1600 m, km2 | % | over 1600 m, km2 | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Balkan Mountains | 4 196,9 | 36,19 | 849 | — | — | 907,1 | 21,61 | 2 074,9 | 49,44 | 1 139,6 | 27,15 | 75,3 | 1,79 |

| Central Balkan Mountains | 3 400,9 | 29,33 | 961 | — | — | 549,8 | 16,17 | 1 512,7 | 44,48 | 1 076,7 | 31,66 | 261,7 | 7,70 |

| Eastern Balkan Mountains | 3 998,6 | 34,48 | 385 | 560 | 14,00 | 2 798,9 | 70,00 | 624,1 | 15,61 | 15,6 | 0,39 | — | — |

| Total | 11 596,4 | 100 | 722 | 560 | 4,83 | 4 255,8 | 36,70 | 4 211,7 | 36,32 | 2 231,9 | 19,25 | 337 | 2,91 |

Hydrology

The Balkan Mountains form a water divide between the rivers flowing to the Danube in the north and those flowing to the Aegean Sea in the south. However, they are crossed by Bulgaria's widest river, the Iskar, which forms the spectacular Iskar Gorge. Rivers that take their source from the Balkan Mountains and flow northwards to the Danube include the Timok, Archar, Lom, Tsibritsa, Ogosta, Skat, Vit, Osam, Yantra, and Rusenski Lom. The mountains are also the source of the Kamchiya, which flows directly into the Black Sea. Although not so abundant in mineral waters as other parts of Bulgaria, there are several spas such as Varshets, Shipkovo and Voneshta Voda.

There are a number of waterfalls, especially in the western and central parts of the range, such as Raysko Praskalo which is the highest waterfall in the Balkan Peninsula, Borov Kamak, Babsko Praskalo, Etropole Waterfall, Karlovsko Praskalo, Skaklya and others. Developments in the recent two decades completely changed the geography of Serbia, when it comes to waterfalls. Area of the Stara Planina has always been sparsely populated and inaccessible because of the rugged and forested terrain, but also as a location of the Serbian-Bulgarian border. As armies relinquished the borders keeping to the police, civilians were allowed to explore the area.[10] As a result, higher and higher waterfalls have been discovered on the Serbian side of the Stara Planina since then: Čungulj in 1996 - 43 m (141 ft);[11] Pilj in 2002 - 64 m (210 ft);[11] Kopren in 2011 - 103.5 m (340 ft);[12] Kaluđerski Skokovi in 2012 - 232 m (761 ft).[13]

Passes

The mountains are crossed by 20 passes and two gorges. There are paved roads crossing the Balkan Mountains at the following passes (listed from west to east):

- Petrohan Pass: Sofia - Montana

- Iskar Gorge (Iskarski prolom): Sofia - Vratsa (also railroad)

- Vitinya Pass: Hemus motorway (A2), Sofia - Botevgrad

- Beklemeto Pass: Troyan - Sopot

- Shipka Pass: Gabrovo - Kazanlak (also railroad)

- Pass of the Republic (Prohod na republikata): Veliko Tarnovo - Gurkovo

- Vratnik Pass: Elena - Sliven

- Kotel Pass (Kotlenski prohod): Kotel - Petolachka (Pentagram) crossroads

- Varbitsa Pass (Varbishki prohod): Shumen - Petolachka crossroads

- Rish Pass (Rishki prohod): Shumen - Karnobat

- Luda Kamchiya Gorge (Ludokamchiyski prolom): Provadiya - Karnobat (also railroad)

- Aytos Pass (Aytoski prohod) - Provadiya - Aytos

- Dyulino Pass (Dyulinski prohod): Varna - Aytos

- Obzor Pass (Obzorski prohod): Varna - Burgas, future Cherno More motorway (A3)

Peaks

- Botev Peak 2,376 m (7,795 ft), named after Hristo Botev.

- Vezhen Peak 2,198 m (7,211 ft)

- Midžor 2,169 m (7,116 ft), the highest peak in Serbia outside of Kosovo and north-western Bulgaria, 12th in the Balkan Mountains.

- Kom Peak 2,016 m (6,614 ft)

- Todorini Kukli 1,785 m (5,856 ft)

- Murgash 1,687 m (5,535 ft)

- Shipka Peak 1,523 m (4,997 ft)

- Buzludzha 1,441 m (4,728 ft)

- Balgarka Peak 1,181 m (3,875 ft)

- Levski Peak (named after Vasil Levski)

- Vetren 1,330 m (4,364 ft)

History

The Balkan Mountains have had a significant and special place in the history of Bulgaria since its founding in 681. It was a natural fortress of the Bulgarian Empire for centuries and formed an effective barrier to Moesia where most of the medieval capitals were located. The Balkan mountains were the site of numerous battles between the Bulgarian and Byzantine Empires including the Battle of the Rishki Pass (759), Battle of the Varbitsa Pass (811), and the Battle of Tryavna (1190). In the battle of the Varbitsa Pass, Khan Krum decisively defeated an enormous Byzantine army, killing Emperor Nikephoros I. For many centuries the Byzantines feared these mountains, and on several occasions Byzantine armies pulled back on approaching the Balkan Mountains.

During the Ottoman rule, many haiduks found refuge in the Balkan Mountains. Close to the highest summit, Botev Peak, is Kalofer, the birthplace of Hristo Botev, a Bulgarian poet and national hero who died in the western Balkan Mountains near Vratsa in 1876 in the struggle against the Ottoman Empire. Also close to Botev Peak is Shipka Pass, the scene of the four battles in the Russo-Turkish War, 1877-78, which ended Turkish rule in the Balkans. Close to the pass in the village of Shipka, there is a Russian Orthodox church built to commemorate Russian and Bulgarian bravery during pass defense.

Protection

Bulgaria

Serbia

First group of trees was protected in 1966, followed by the creation of 7 special nature reserves and 3 natural monuments in the 1980s. Nature park Stara Planina was established in 1997 and since 2009 is in its present borders, covering an area of 1,143.22 km2 (441.40 sq mi).[14]

Limestone terrain is known for the short losing streams and tufaceous waterfalls. There are canyons and gorges, like those of the Toplodolska reka and Rosomačka reka rivers. Underground waters on the mountain reach the surface in the forms of common springs, well-springs (vrelo) and diffused springs (pištevina). There are some 500 springs with the flow of over 0.1 L/s (1.3 imp gal/min). The strongest spring is the intermittent Jelovičko vrelo, known for its fluctuations, characterized by the bubbling and foaming.[15]

Montane ecosystems are diverse and include several plant communities: forests, shrubs, meadows, pastures and peatlands. There are six different vegetation zone in the park. Oak, beech, spruce, subalpine zone of the shrub vegetation of common horsetail, blueberry, subalpine spruce and mugo pine. Other plants include shrub alder, steppe pedunculate oak, but also rare and endangered species like European pasqueflower, yellow pheasant's eye, Kosovo peony, common sundew, Heldreich's maple, martagon lily, pygmy iris and marsh orchid.[15]

The area is a salmonid region, inhabited by the riverine brown trout. Another 25 species of fish live in the rivers and streams, so as the fire salamander and newts. There are 203 species of birds, of which 154 are nesting in the park, 10 are wintering, 30 are passing and 13 are wandering. Important species include golden eagle, Ural owl and hawk. As the park is the most important habitat in Serbia for long-legged buzzard, Eurasian woodcock and an endemic Balkan horned lark, an area of 440 km2 (170 sq mi) was declared a European Important Bird Area. The griffon vulture disappeared from the region in the late 1940s. In 2017 a program for their reintroduction began within the scope of a wider European program. Among other things, the feeders will be placed along the vultures' migratory route. Over 30 mammalian species are found in the park, including lesser mole-rat, hazel dormouse and the Tertiary relict, European snow vole.[15][16]

Human heritage spans from the prehistoric remains, Classical antiquity including the Roman period and late mediaeval monastic complexes. Some of those older monuments are fragmentary and relocated from their original locations. There are numerous examples of the ethnic edifices characteristic for the architecture of the region in the late 19th and early 20th century (houses, barns, etc.)[15]

Serbian section of the mountain is seen as a location for dozens of micro hydros, mini power plants which caused problem with the environmentalists and local population. Even the Ministry for environmental protection halted some of the projects and litigated with the investors. They also announced the change of the Nature protection law, which will permanently forbid the construction of plants in protected areas. In order to prevent further degradation, the Nature Park Stara Planina was nominated for the UNESCO's Man and the Biosphere Programme and for the world list of geoparks, while over tens of thousands of citizens signed petitions against the micro hydros and numerous protests have been organized by the local population.[17]

See also

- Balkans

- Bulgarka Nature Park

- Kom–Emine, a high-mountain long-distance trail along the main ridge of the Balkan Mountains

- Rhodope Mountains, Rila, Pirin, Dinaric Alps, Šar mountain, Pindus, Strandzha — other major mountain chains in the Balkan region

- Svishtiplaz

Notes and references

- 1 2 Bulgaria. 1986.

- ↑ Андрейчин Л. и др., Български тълковен речник (допълнен и преработен от Д. Попов). Четвърто преработено и допълнено издание.: Издателство “Наука и изкуство”. С., 1994

- ↑ Todorova, Maria N. (1997). Imagining the Balkans. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-19-508751-2.

- ↑ "Balkhan Mountains". World Land Features Database. Land.WorldCityDB.com. Archived from the original on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

- ↑ "Balkan". Encarta World English Dictionary. Microsoft Corporation. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

- ↑ "balkan". Büyük Türkçe Sözlük (in Turkish). Türk Dil Kurumu. Archived from the original on 2011-08-25.

Sarp ve ormanlık sıradağ

- ↑ Balkan studies. Édition de lA̕cadémie bulgare des sciences. 1986.

- ↑ Apollodorus (1976). Gods and Heroes of the Greeks: The Library of Apollodorus. Univ of Massachusetts Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-87023-206-1.

- ↑ "SummitPost - Stara Planina (Balkana) -- Climbing, Hiking & Mountaineering". www.summitpost.org. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-14.

- ↑ Senka Lučić (4 April 2012), "Koprenski vodopad", Politika-Putovanja (in Serbian), p. 06

- 1 2 "Menjaju geografiju". Politika (in Serbian). 1 May 2006. p. 10.

- ↑ vodopadisrbije.com Kopren (Stara planina)

- ↑ Jelena Đokić (2015). "Vodopadi Srbije: Skriveni dragulji Stare planine" (in Serbian). Portal Mladi.

- ↑ Park prirode Stara Planina (PDF). Institute for nature conservation of Serbia. 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Dr Dušan Mijović (30 July 2009), "Vrela Stare Planine", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ Branka Vasiljević (5 September 2017), "Nekontrolisane posete turista ugrožavaju opstanak beloglavnog supa", Politika (in Serbian), p. 14

- ↑ Slavica Stuparušić (21 August 2018). "Meštani i ekolozi nastavljaju da se bore za Visočicu na Staroj planini" [Denizens ad ecologists continue to fight for the Visočica and Stara Pazova]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 08.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Balkan Mountains. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stara planina (Balkan Mountains). |

.svg.png)