Leontopodium nivale

| Edelweiss | |

|---|---|

| Close-up of flower. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae |

| Genus: | Leontopodium |

| Species: | L. nivale |

| Binomial name | |

| Leontopodium nivale (Ten.) Huet ex Hand.-Mazz. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Leontopodium alpinum Colm. ex Cass. | |

Leontopodium nivale, commonly called edelweiss (English pronunciation /ˈeɪdəlvaɪs/ (![]()

The plant prefers rocky limestone places at about 1,800–3,000 metres (5,900–9,800 ft) altitude. It is non-toxic, and has been used in traditional medicine or folk medicine as a remedy against abdominal and respiratory diseases. The dense hair appears to be an adaptation to high altitudes, protecting the plant from cold, aridity, and ultraviolet radiation.[1] As a scarce, short-lived flower found in remote mountain areas, the plant has been used as a symbol for alpinism, for rugged beauty and purity associated with the Alps and Carpathians, and as a national symbol, especially of Romania, Austria, Bulgaria, Slovenia, and Switzerland. According to folk tradition, giving this flower to a loved one is a promise of dedication.

Names

The flower's common name derives from the German word "Edelweiß", which is a compound of edel "noble" and weiß "white". In Romania it's known as Floare de colț which means Cliffhanger's flower. In the Italian speaking Alps the flower is referred as "Stella Alpina", while in the French Alps as "Étoile des Alpes", both names meaning "Star of the Alps".[2]

Edelweiß was one of several regional names for the plant and entered wide usage during the first half of the 19th century, in the context of early Alpine tourism.[3] Alternative names include Chatzen-Talpen ("cat's paws"), and the older Wullbluomen ("wool flower", attested in the 16th century).[4][5]

The scientific name is a latinisation of the Greek leontopódion, "lion's paw".[6]

Taxonomy

Since 1822, Leontopodium has no longer been considered part of the genus Gnaphalium, but classified alongside it as a distinct genus within the tribe Gnaphalieae. In 2003, Leontopodium alpinum was re-classified as a subspecies of Leontopodium nivale. Thus, the alpine edelweiss is currently recognized as being divided into two subspecies, Leontopodium nivale subsp. alpinum (Cass.) Greuter and Leontopodium nivale subsp. nivale.[7]

Description

The plant's leaves and flowers are covered with white hairs, and appear woolly (tomentose). Flowering stalks of edelweiss can grow to a size of 3–20 centimetres (1–8 in) in the wild, or, up to 40 cm (16 in) in cultivation. Each bloom consists of five to six small yellow clustered spikelet-florets (5 mm, 3⁄16 in) surrounded by fuzzy white "petals" (technically, bracts) in a double-star formation. The flowers bloom between July and September.

Early-season version with central floret-pods not yet fully developed. Specimen found in Slovakia's Tatra Mountains.

Early-season version with central floret-pods not yet fully developed. Specimen found in Slovakia's Tatra Mountains. Typical mid-season appearance. Specimen found in Italy's Bergamo Alps.

Typical mid-season appearance. Specimen found in Italy's Bergamo Alps. Late season version with "fat" appearance from flowered-out central floret-pods and from longer petal-"fuzz".[8] Specimen found in the Stubai Alps.[9]

Late season version with "fat" appearance from flowered-out central floret-pods and from longer petal-"fuzz".[8] Specimen found in the Stubai Alps.[9] Botanic illustration.

Botanic illustration.

Conservation

Leontopodium nivale is considered a least concern species by the IUCN.[10] The population of this species declined due to overcollection, but is now protected by laws, ex situ conservation and occurrence in national parks.[10]

Cultivation

Leontopodium nivale is grown in gardens for its interesting inflorescence and silver foliage.[11] The plants are short lived and can be grown from seed.[12]

Chemical constituents

Compounds of different classes, such as terpenoids, phenylpropanoids, fatty acids and polyacetylenes are reported in various parts of edelweiss.[13] Leoligin was reported as the major lignan constituent.[14]

Symbolic uses

%2C_chromolithograph_by_Helga_von_Cramm%2C_with_hymn_by_F._R._Havergal%2C_1877.jpg)

In the 19th century, the edelweiss became a symbol of the rugged purity of the Alpine region and of its native inhabitants.

In Berthold Auerbach's novel Edelweiss (1861), the difficulty for an alpinist to acquire an edelweiss flower was exaggerated to the point of claiming: "the possession of one is a proof of unusual daring."[15] This idea at the time was becoming part of the popular mythology of early alpinism.[16] Auerbach's novel appeared in English translation in 1869, prefaced with a quote attributed to Ralph Waldo Emerson:

- "There is a flower known to botanists, one of the same genus with our summer plant called "Life-Everlasting," a Gnaphalium like that, which grows on the most inaccessible cliffs of the Tyrolese mountains, where the chamois dare hardly venture, and which the hunter, tempted by its beauty, and by his love (for it is immensely valued by the Swiss maidens), climbs the cliffs to gather, and is sometimes found dead at the foot, with the flower in his hand. It is called by botanists the Gnaphalium leontopodium, but by the Swiss Edelweisse, which signifies Noble Purity."

- Before 1914

- in the Swiss army, the highest ranks (brigadier general and higher) have badges in the form of edelweiss flowers, where other military branch badges would have stars

- The edelweiss was established in 1907 as the sign of the Austrian-Hungarian alpine troops by Emperor Franz Joseph I. These original three Regiments wore their edelweiss on the collar of their uniform. During World War I (1915), the edelweiss was granted to the German alpine troops, for their bravery. Today, it is still the insignia of the Austrian, French, Slovenian, Polish, Romanian, and German alpine troops

- World Wars era

- The song Stelutis alpinis (Friulian for "alpine edelweiss"), written by Arturo Zardini when he was an evacuee due to World War I, is now considered the unofficial anthem of Friuli[17]

- The song Es War Ein Edelweiss was written by Herms Niel for soldiers during World War II

- The edelweiss was a badge of the Edelweiss Pirates: the anti-Nazi youth groups in the Third Reich. It was worn on the clothes (e.g., a blouse or a suit)

- The edelweiss flower was the symbol of Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS Gebirgsjäger, or mountain rangers, worn as a metal pin on the left side of the mountain cap, on the band of the service dress cap, and as a patch on the right sleeve. It is still the symbol of the mountain brigade in the German army today

- The World War II Luftwaffe unit, Kampfgeschwader 51 (51st Bomber Wing) was known as the Edelweiss Wing

- The edelweiss is represented as the favorite flower of Adolf Hitler's, in the recording "Adolf Hitlers Lieblingsblume ist das schlichte Edelweiß" (1934), sung by Harry Steier[18]

- After 1945

- The edelweiss flower is a common symbol worn by today's United States Army's 1st Battalion 10th Special Forces Group Airborne Soldiers. The 1-10th SFG(A) Soldiers adopted the symbol under the command of (Ret.) Col. Aaron Banks after they occupied the former Waffen SS officer school (Junkerschule) at Flint Kaserne

- A song entitled "Edelweiss" was written for Rodgers and Hammerstein's musical The Sound of Music (1959)

- Since 2002, the Austrian two cent coin has depicted an edelweiss

- From 1959 to 2001, the one schilling coin depicted a bunch of three flowers

- It is the symbol of the Bulgarian Tourist Union and the Bulgarian Mountain Control and Lifeguard Service

- It is also the symbol of the Swiss national tourism organisation

- It is featured on the Romanian fifty lei note

- An Austrian brand of beer is named Edelweiß

- The edelweiss is used in the logotypes of several alpine clubs such as the Deutscher Alpenverein (German Alpine Club) or the Österreichischer Alpenverein (Austrian Alpine Club). The edelweiss is also used in the logotype of the Union of International Mountain Leader Associations (UIMLA).

- In Asterix in Switzerland (1970), the plot is driven by a quest to find edelweiss in the Swiss mountains and bring a bloom back to Gaul to cure a poisoned Roman quaestor

- Edelweiss Air, an international airline based in Switzerland, is named after the flower, which also appears in its logo

- The musician Moondog composed the song "High on a Rocky Ledge" inspired by the Edelweiss flower

- "Bring me Edelweiss" is the best-known song of the music group Edelweiss

- Polish professional ice hockey team MMKS Podhale Nowy Targ use an edelweiss as their emblem

- Edelweiss Lodge and Resort is a military resort located in Garmisch, Germany

Symbolic use-image gallery

- Some symbolic use from ancient times to the present

1963 German mountain sport pin.

1963 German mountain sport pin. German Alpine Club logo pin.[19]

German Alpine Club logo pin.[19] On a Romanian fifty lei note.

On a Romanian fifty lei note. Logo of the Union of International Mountain Leader Associations.

Logo of the Union of International Mountain Leader Associations. Logo of Croatian Mountain Rescue Service

Logo of Croatian Mountain Rescue Service

.jpg) Nazi-era nose art on a bomber from the "Edelweiss Wing" (KG 51).

Nazi-era nose art on a bomber from the "Edelweiss Wing" (KG 51). Nazi-era photo with KG 51 insignia on a Ju 88 bomber.

Nazi-era photo with KG 51 insignia on a Ju 88 bomber. 1939 Nazi-era aircraft nose art.

1939 Nazi-era aircraft nose art.- French mountain troops school emblem.[20]

Logo of German sports association RMSV.

Logo of German sports association RMSV. Rank insignia in the Swiss postal service.

Rank insignia in the Swiss postal service.- German Federal Police rank insignia patch.

Kyrgyz postage stamp from 1994.

Kyrgyz postage stamp from 1994. West German postage stamp from 1975.

West German postage stamp from 1975. On 2004 Swiss coin.

On 2004 Swiss coin. On 1925 gold 100 Swiss francs coin.

On 1925 gold 100 Swiss francs coin. On 1983 Austrian schilling.

On 1983 Austrian schilling. Kazakhstan 500 tenge coin.

Kazakhstan 500 tenge coin. Four-"Star" rank insignia of the top Swiss general.

Four-"Star" rank insignia of the top Swiss general. Austrian army JgB 23 emblem.

Austrian army JgB 23 emblem. West/German military "Allgäu" fighter/bomber group 1958–2003.

West/German military "Allgäu" fighter/bomber group 1958–2003..svg.png) West/German military 23rd mountain rifles troops emblem.

West/German military 23rd mountain rifles troops emblem. Insignia of the Polish Army Podhale Rifles.

Insignia of the Polish Army Podhale Rifles. Insignia of the Polish Army 21st Podhale Rifles Brigade.

Insignia of the Polish Army 21st Podhale Rifles Brigade. Russian military 17 ОСН "Edelweiss" emblem.

Russian military 17 ОСН "Edelweiss" emblem. Austrian army JgB 6 emblem.

Austrian army JgB 6 emblem. Arms of Vaujany, France.

Arms of Vaujany, France. Arms of Au, Austria.

Arms of Au, Austria. Arms of the county of Brașov, Romania.

Arms of the county of Brașov, Romania. Arms of Dramsha, Bulgaria.

Arms of Dramsha, Bulgaria..svg.png) Arms of Bonnefamille, France.

Arms of Bonnefamille, France..svg.png) Arms of Chamonix-Mont-Blanc, France.

Arms of Chamonix-Mont-Blanc, France. Arms of Carroz d'Arâches, France.

Arms of Carroz d'Arâches, France. Arms of Eisenärzt, Germany.

Arms of Eisenärzt, Germany. Logo of Edelweiss Beer.

Logo of Edelweiss Beer. General's "star" on the saddle of World War I-era Swiss commander Ulrich Wille.

General's "star" on the saddle of World War I-era Swiss commander Ulrich Wille. On the hat and collar circa 1933 of Austria's Engelbert Dollfuss.

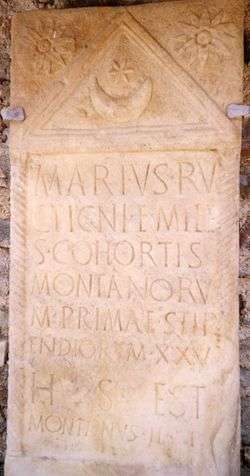

On the hat and collar circa 1933 of Austria's Engelbert Dollfuss. Imperial Roman tombstone of Austrian soldier Marius son of Ructinus.

Imperial Roman tombstone of Austrian soldier Marius son of Ructinus.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edelweiss in art. |

See also

References

- ↑ Vigneron, Jean Pol; Marie Rassart; Zofia Vértesy; Krisztián Kertész; Michaël Sarrazin; László P. Biró; Damien Ertz; Virginie Lousse (January 2005). "Optical structure and function of the white filamentary hair covering the edelweiss bracts". Physical Review E. American Physical Society. 71. arXiv:0710.2695. Bibcode:2005PhRvE..71a1906V. doi:10.1103/physreve.71.011906.

- ↑ William Shepard Walsh (1909). Handy-book of literary curiosities. J.B. Lippincott Co. pp. 268–. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

- ↑ Edelweiss reported as common name alongside Alpen-Ruhrkraut in Kittel, Taschenbuch der Flora Deutschlands zum bequemen Gebrauch auf botanischen Excursionen (1837), p. 383.

- ↑ Aretius, Stocc-Hornii et Nessi [...] descriptio [...], a Benedicto Aretio [...] dictata., published with Valerii Cordi Simesusii Annotationes in Pedacii Dioscoridis Anazarbei de medica materia libros V, Basel (1561), ed. Bratschi (1992) in Niesen und Stockhorn. Berg-Besteigungen im 16. Jahrhunder.

- ↑ Schweizerisches Idiotikon 16.1997 Archived 2013-12-13 at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ λέων, πόδιον, πούς. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ↑ "Leontopodium nivale (Ten.) Huet ex Hand.-Mazz. — The Plant List". www.theplantlist.org. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

- ↑ NOTE: Sometimes mistaken for a different species (reference only).

- ↑ NOTE: Image courtesy of Bernd Haynold (reference only).

- 1 2 "Leontopodium alpinum (Edelweiss)". www.iucnredlist.org. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

- ↑ Mineo, Baldassare (1999). Rock garden plants: a color encyclopedia. Portland, Or.: Timber Press. p. 150. ISBN 0-88192-432-6.

- ↑ McVicar, Jekka. Seeds: The Ultimate Guide to Growing Successfully from Seed. The Lyons Press. p. 22. ISBN 1-58574-874-9.

- ↑ Tauchen, J. & Kokoska, L. Phytochem Rev (2017) 16: 295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11101-016-9474-0

- ↑ Wang L, Ladurner A, Latkolik S, Schwaiger S, Linder T, Hošek J, Palme V, Schilcher N, Polanský O, Heiss EH, Stangl H, Mihovilovic MD, Stuppner H, Dirsch VM, Atanasov AG. Leoligin, the Major Lignan from Edelweiss (Leontopodium nivale subsp. alpinum), Promotes Cholesterol Efflux from THP-1 Macrophages. J Nat Prod. 2016 Jun 24;79(6):1651-7. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00227.

- ↑ Berthold Auerbach (1869). Edelweiss: A story. Roberts Brothers. p. 77.

- ↑ "Chamois hunting". New monthly magazine and universal register. 1853. p. 166.

- ↑ (in Italian) Screm, Alessio (April 6, 2016). "I friulani scelgono il loro inno: è “Stelutis alpinis” di Zardini" . Messaggero Veneto. Retrieved 2017-03-10.

- ↑ "Lied der U-Boot-Männer (Ob Öltanker, ob Kauffahrtei...) - Axis History Forum". forum.axishistory.com. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

- ↑ NOTE: DAV on this pin means Deutscher Alpenverein not Disabled American Veterans for which such pins may be confused (reference only).

- ↑ NOTE: CIECM meaning Centre d' Instruction et d' Entraînement au Combat en Montagne (reference only).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leontopodium nivale. |