Nùng people

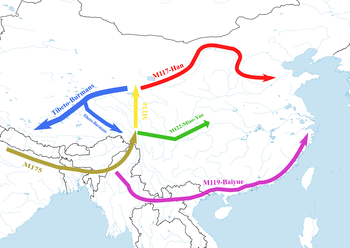

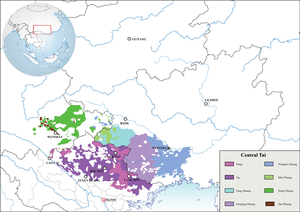

Geographic distribution of the Nung as a part of Central Tai speaking peoples | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Vietnam, China | |

| 968,800 (2009)[1] | |

| unknown | |

| Languages | |

| Nung, Vietnamese, Chinese | |

| Religion | |

| Nung folk religion,[2] Moism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Zhuang people and Tày people | |

The Nung (pronounced as noong [nuːŋ]) are a Central Tai ethnic group living primarily in northeastern Vietnam and southwestern Guangxi. The Nung sometimes call themselves as Tho, which literally means autochthonous (indigenous or native to the land). Their ethnonym is often mingled with that of the Tày as Tày-Nùng.

According to the Vietnam census, the population of the Nung numbered about 856,412 by 1999 and 968,800 by 2009. They are the third largest Tai-speaking group, preceded by the Tày and the Thái (Black Tai, White Tai and Red Tai groups), and sixth overall among national minority groups.

They are closely related to the Tày and the Zhuang. In China, the Nung, together with the Tày, are classified as Zhuang people.

In 1954, several thousand Nung Phàn Slình came to South Vietnam as refugees and settled in Tuyen Duc province.[3] Following the Sino-Vietnamese war, there were further waves of migration to the Central Highlands.

Subdivisions

There are several subgroups among the Nung: Nung Xuồng, Nung Giang, Nung An, Nung Phàn Slình, Nung Lòi, Nung Cháo, Nung Quý Rỉn, Nung Dín, Nung Inh, Nung Tùng Slìn etc.

Many of the Nung's sub-group names correspond to the geographic regions of the Nung homeland. Hoàng Nam (2008:11) lists the following Nùng subgroups.[4]

- Nung Inh: migrated from Long Ying

- Nung Phàn Slình: migrated from Wan Cheng

- Nung Phàn Slình thua lài

- Nung Phàn Slình cúm cọt

- Nung An: migrated from An Jie

- Nung Dín

- Nung Lòi: migrated from Xia Lei

- Nung Tùng Slìn: migrated from Cong Shan

- Nung Quý Rỉn: migrated from Gui Shun

- Nung Cháo: migrated from Long Zhou

History

Origins

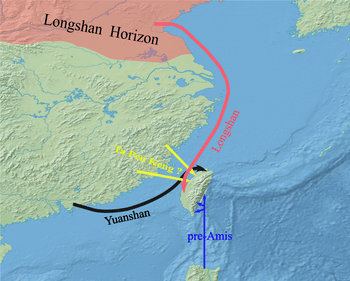

Nung has traditionally been classified as a Central Tai language within Kra-Dai or Daic (also Kadai, Tai-Kadai or Zhuàng-Dòng) family. The Kra-Dai speaking peoples living across a substantial region of East and Southeast Asia are commonly considered to originate in South China. Although the position of Kra-Dai in relation to Austronesian is still attested, the generally accepted hypothesis has it that Kra-Dai and Austronesian are genetically connected. Weera Ostapirat (2005) sets out a series of regular sound correspondences between them, assuming a model of a primary split between the two; they would then be co-ordinate branches.[5] Weera Ostapirat (2013) continues to maintain that Kra-Dai and Austronesian are sister languages, based on some phonological correspondences.[6] On the other hand, Laurent Sagart (2008) proposes that Kra-Dai is a later form of FATK,[lower-alpha 1] a branch of Austronesian belonging to subgroup Puluqic developed in Taiwan, whose speakers migrated back to the mainland, both to Guangdong, Hainan and north Vietnam around the second half of the 3rd millennium BCE.[7] Upon their arrival in this region, they underwent linguistic contact with an unknown population, resulting in a partial relexification of FATK vocabulary.[8]

Researches into the origins of the Austronesian languages have still remained controversial with two competing hypotheses. The first hypothesis is supported by Robert Blust, which connects lower Yangtze neolithic Austro-Tai entity with the rice-cultivating Austro-Asiatic cultures, assuming the center of East Asian rice domestication, and putative Austric homeland, to be located in the Yunnan/Burma border area.[9] Under that view, there was an east-west genetic alignment, resulting from a rice-based population expansion, in the southern part of East Asia: Austroasiatic-Kra-Dai-Austronesian, with unrelated Sino-Tibetan occupying a more northerly tier.[9] The second one is Sino-Tibetan-Austronesian hypothesis proposed by Laurent Sagart, which argues for a north-south genetic relationship between Chinese and Austronesian, based on sound correspondences in the basic vocabulary and morphological parallels.[9] Laurent Sagart (2017) concludes that the possession of the two kinds of millets[lower-alpha 2] in Taiwanese Austronesian languages (not just Setaria, as previously thought) places the pre-Austronesians in northeastern China, adjacent to the probable Sino-Tibetan homeland.[9] Ko et al.'s genetic research (2014) appears to support Laurent Sagart's linguistic proposal, pointing out that the exclusively Austronesian mtDNA E-haplogroup and the largely Sino-Tibetan M9a haplogroup are twin sisters, indicative of an intimate connection between the early Austronesian and Sino-Tibetan maternal gene pools, at least.[10][11] Additionally, results from Wei et al. (2017) are also in agreement with Sagart's proposal, in which their analyses show that the predominantly Austronesian Y-DNA haplogroup O3a2b*-P164(xM134) belongs to a newly defined haplogroup O3a2b2-N6 being widely distributed along the eastern coastal regions of Asia, from Korea to Vietnam.[12] Another paper by McColl et al. (2018) indicates that the Taiwanese Austronesian are a mixture of an Onge-like population and a population related to the Tianyuan ancient individual.[13]

If Sagart's theory that Kra-Dai being a sub-group of proto-Austronesian migrated out of Taiwan and back to the coastal regions of Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, and (possibly) Vietnam is right, they would simply not have had a development resembling anything like the fate of other proto-Austronesian languages that migrated out of Taiwan to the Philippines and other islands in Southeast Asia.[14] Besides various concrete evidence for a Kra-Dai existence in the present-day Guangdong, remnants of Kra-Dai languages spoken further north could be found in unearthed inscriptional materials and non-Han substrata in Min- and Wu-Chinese dialects.

Wolfgang Behr (2006, 2009) points out that most of non-Sinitic words found in Chu inscriptional materials are of Kra-Dai origin. A few examples that look as if they may be related to Austroasiatic and Miao-Yao are from edited texts of the mid-Han period and later.[15] The most notable item that Wolfang Behr shows is the Chu graph for "one, once" written as ![]()

- PROTECT, COVER[17]

「揞、揜、錯、摩,藏也。荊楚曰揞,吳揚曰揜,周秦曰錯,陳之東鄙曰摩。」

「揞」ăn < MC *ʔomX < OC *ʔʔəm-q ← proto-Tai *homB1 (Siamese homB1, Longzhou humB1, Bo'ai hɔmB1, Lao hom, Ahom hum etc.) "cover up" | proto-Kam-Sui *zumHɣC1 "hide, cover up"

- GRASSHOPPER/LOCUST[18]

「蟒,…南楚之外謂之蟅蟒。」

「蟅」zhē < MC *tsyæ < OC *ttak ← proto-Kam-Sui *thrak7-it (Mulam -hɣak8-t, Kam ʈak7-it, Then zjak7, Sui ndjak7 “grasshopper”)

- PIG, HOG[18]

「猪,…南楚謂之豨。」

「豨」xī < MC *xjɨj < OC *hləj-q ← PKS *ʔdlaaj5 (> Kam (h)laa:i5) “pig”

- "GET BETTER" (of ailments): “ 智于身”[19]

知~![]()

「知」,愈也。南楚病愈者…或謂之知"

"zhī means 'to get better'. In Southern Chǔ , when a sickness gets better ... this is occasionally called zhī." ← proto-Tai *ʔdiiA1 “be good, better” (Siamese diiA1, Longzhou daiA1, Bo'ai niiA1)

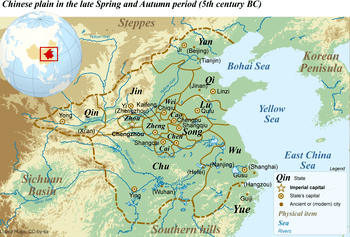

- MOTHER, FEMALE, LADY in Spring and Autumn Chŭ (5th c. B.C.)[20]

嬭 mĭ < *mjieX < *mej-q ← proto-Tai *mɛɛB, proto-Kam-Sui *mlɛɛB, proto-Hlai *mʔaiB vs. proto-Austro-Asiatic *me-q, proto-Mon *meʔ, proto-Katuic *mɛ(:)ʔ “mother”

- ONE, ONCE, BE UNIFIED, BE UNIQUE in Warring States Chŭ[21]

Bronze inscriptions-standard: 一, 壹, 弌 yī < *ʔjit < *ʔit "one, be / become one" etc. (> all later Sinitic languages)

Warring States-Chŭ dialect: 「![]()

cf. 「其義![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

← proto-Tai *hnïŋ = *hnɯŋ (Siamese 22nɯŋ, Dai 33nɯŋ, Longzhou nəəŋA etc.) "one, once"

- WHITE[22]

「𩫁」 ← p[高] gāo < MC *kaw < OC *kkaw ← proto-Tai *xaauA1 (Siamese, Longzhou khaauA1, Bo'ai haauA1) "white" (cf. proto-Mon *klaɨA “white”)

- THICK[23]

「![]()

In the early 1980s, Zhuang linguist, Wei Qingwen (韦庆稳), electrified the scholarly community in Guangxi by identifying the language in the "Song of the Yue People" as a language ancestral to Zhuang.[24] Wei used reconstructed Old Chinese for the characters and discovered that the resulting vocabulary showed strong resemblance to modern Zhuang.[25] Later, Zhengzhang Shangfang (1991) followed Wei’s insight but used Thai script for comparison, since this orthography dates from the 13th century and preserves archaisms viz-à-viz the modern pronunciation.[25][26] The following is a simplified interpretation of the "Song of the Yue People" by Zhengzhang Shangfang quoted by David Holm (2013) with Thai script and Chinese glosses being omitted:[27][lower-alpha 3]

| 濫 | 兮 | 抃 | 草 | 濫 | ||||||||||||

| ɦgraams | ɦee | brons | tshuuʔ | ɦgraams | ||||||||||||

| glamx | ɦee | blɤɤn | cɤɤ, cɤʔ | glamx | ||||||||||||

| evening | ptl. | joyful | to meet | evening | ||||||||||||

| Oh, the fine night, we meet in happiness tonight! | ||||||||||||||||

| 予 | 昌 | 枑 | 澤 | 予 | 昌 | 州 | ||||||||||

| la | thjang < khljang | gaah | draag | la | thjang | tju < klju | ||||||||||

| raa | djaangh | kraʔ - | ʔdaak | raa | djaangh | cɛɛu | ||||||||||

| we, I | be apt to | shy, ashamed | we, I | be good at | to row | |||||||||||

| I am so shy, ah! I am good at rowing. | ||||||||||||||||

| 州 | 𩜱 | 州 | 焉 | 乎 | 秦 | 胥 胥 | ||||||||||

| tju | khaamʔ | tju | jen | ɦaa | dzin | sa | ||||||||||

| cɛɛu | khaamx | cɛɛu | jɤɤnh | ɦaa | djɯɯnh | saʔ | ||||||||||

| to row | to cross | to row | slowly | ptl. | joyful | satisfy, please | ||||||||||

| Rowing slowly across the river, ah! I am so pleased! | ||||||||||||||||

| 縵 | 予 | 乎 | 昭 | 澶 | 秦 | 踰 | ||||||||||

| moons | la | ɦaa | tjau < kljau | daans | dzin | lo | ||||||||||

| mɔɔm | raa | ɦaa | caux | daanh | djin | ruux | ||||||||||

| dirty, ragged | we, I | ptl. | prince | Your Excellency | acquainted | know | ||||||||||

| Dirty though I am, ah! I made acquaintance with your highness the Prince. | ||||||||||||||||

| 滲 | 惿 | 隨 | 河 | 湖 | ||||||||||||

| srɯms | djeʔ < gljeʔ | sɦloi | gaai | gaa | ||||||||||||

| zumh | caï | rɯaih | graih | gaʔ | ||||||||||||

| to hide | heart | forever, constantly | to yearn | ptl. | ||||||||||||

| Hidden forever in my heart, ah! is my adoration and longing. | ||||||||||||||||

This is one of a number of interpretations of this poem.[24] Zhengzhang notes that 'evening, night, dark' bears the C tone in Wuming Zhuang xamC2 and ɣamC2 'night'. The item raa normally means 'we inclusive' but in some places, e.g. Tai Lue and White Tai 'I'.[28] Zhengzhang's interpretation of the song receives criticism from Laurent Sagart as he claims that Chinese scholars often associate the Yue language with Tai-Kadai.[29]

Li Hui (2001) finds 126 Kra-Dai cognates in Maqiao Wu dialect spoken in the suburbs of Shanghai out of more than a thousand lexical items surveyed.[30] According to the author, these cognates are likely traces of 'old Yue language' (gu Yueyu 古越語).[30] The two tables below show lexical comparisons between Maqiao Wu dialect and Kra-Dai languages quoted from Li Hui (2001). He notes that, in Wu dialect, final consonants such as -m, -ɯ, -i, ụ, etc don't exist, and therefore, -m in Maqiao dialect tends to become -ŋ or -n, or it's simply absent, and in some cases -m even becomes final glottal stop.[31]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Some scattered non-Sinitic words found in the two ancient Chinese fictional texts, Mu tianzi zhuan 穆天子傳 (4th c. B.C.) and Yuejue shu 越絕書 (1st c. A.D.), can be compared to lexical items in Kra-Dai languages. These two texts are only preserved in corrupt versions and share a rather convoluted editorial history. Wolfgang Behr (2002) makes an attempt to identify the origins of those words:

- "吳謂善「伊」, 謂稻道「缓」, 號從中國, 名從主人。"[32]

“The Wú say yī for ‘good’ and huăn for ‘way’, i.e. in their titles they follow the central kingdoms, but in their names they follow their own lords.”

伊 yī < ʔjij < *bq(l)ij ← Siamese diiA1, Longzhou dai1, Bo'ai nii1 Daiya li1, Sipsongpanna di1, Dehong li6 < proto-Tai *ʔdɛiA1 | Sui ʔdaai1, Kam laai1, Maonan ʔdaai1, Mak ʔdaai6 < proto-Kam-Sui/proto-Kam-Tai *ʔdaai1 'good'

缓 [huăn] < hwanX < *awan ← Siamese honA1, Bo'ai hɔn1, Dioi thon1 < proto-Tai *xronA1| Sui khwən1-i, Kam khwən1, Maonan khun1-i, Mulam khwən1-i < proto-Kam-Sui *khwən1 'road, way' | proto-Hlai *kuun1 || proto-Austronesian *Zalan (Thurgood 1994:353)

絕 jué < dzjwet < *bdzot ← Siamese codD1 'to record, mark' (Zhengzhang Shangfang 1999:8)

- "姑中山者越銅官之山也, 越人謂之銅, 「姑[沽]瀆」。"[33]

“The Middle mountains of Gū are the mountains of the Yuè’s bronze office, the Yuè people call them ‘Bronze gū[gū]dú.”

「姑[沽]瀆」 gūdú < ku=duwk < *aka=alok

← Siamese kʰauA1 'horn', Daiya xau5, Sipsongpanna xau1, Dehong xau1, Lü xău1, Dioi kaou1 'mountain, hill' < proto-Tai *kʰauA2; Siamese luukD2l 'classifier for mountains', Siamese kʰauA1-luukD2l 'mountain' || cf. OC 谷 gǔ < kuwk << *ak-lok/luwk < *akə-lok/yowk < *blok 'valley'

- "越人謂船爲「須盧」。"[34]

"... The Yuè people call a boat xūlú. (‘beard’ & ‘cottage’)"

須 xū < sju < *bs(n)o

? ← Siamese saʔ 'noun prefix'

盧 lú < lu < *bra

← Siamese rɯaA2, Longzhou lɯɯ2, Bo'ai luu2, Daiya hə2, Dehong hə2 'boat' < proto-Tai *drɯ[a,o] | Sui lwa1/ʔda1, Kam lo1/lwa1, Be zoa < proto-Kam-Sui *s-lwa(n)A1 'boat'

- "[劉]賈築吳市西城, 名曰「定錯」城。"[35]

"[Líu] Jiă (the king of Jīng 荆) built the western wall, it was called dìngcuò ['settle(d)' & 'grindstone'] wall."

定 dìng < dengH < *adeng-s

← Siamese diaaŋA1, Daiya tʂhəŋ2, Sipsongpanna tseŋ2 'wall'

錯 cuò < tshak < *atshak

? ← Siamese tokD1s 'to set→sunset→west' (tawan-tok 'sun-set' = 'west'); Longzhou tuk7, Bo'ai tɔk7, Daiya tok7, Sipsongpanna tok7 < proto-Tai *tokD1s ǀ Sui tok7, Mak tok7, Maonan tɔk < proto-Kam-Sui *tɔkD1

James R. Chamberlain (2016) proposes that Kra-Dai language family was formed as early as the 12th century BCE in the middle Yangtze basin, coinciding roughly with the establishment of the Chu fiefdom and the beginning of the Zhou dynasty.[36] Following the southward migrations of Kra and Hlai (Rei/Li) peoples from the ancient state of Chu around the 8th century BCE, the Be-Tai people started to break away to the east coast in the present-day Zhejiang, in the 6th century BCE, establishing the state of Yue.[36] After the destruction of the state of Yue by Chu army around 333 BCE, Yue people (Be-Tai) began to migrate southwards along the east coast of China to what are now Guangxi, Guizhou and northern Vietnam, forming Luo Yue (Central-Southwestern Tai) and Xi Ou (Northern Tai).[36]

From the Middle Ages to the Present

In 1038, Nùng Tồn Phúc (Nong Quanfu, Chinese: 儂全福), a Nùng chieftain, proclaimed the founding of the Kingdom of Longevity (Chang Qi Guo 長生國). The king of Annamese kingdom, Dai Co Viet, led an army into the region in the third month of 1039, captured Nùng Tồn Phúc and most of his family, and returned them to Dai Co Viet for execution. His 14-year-old son, Nùng Trí Cao (Nong Zhigao, Chinese: 儂智高), evaded capture.[37] Nùng Trí Cao then rose up three times in 1041, 1048, 1052. But finally he was defeated by the Song, a Chinese dynasty at that times. After the defeat of Nùng Trí Cao, Many of the Nùng rebels fled to Vietnam, concentrating around Cao Bằng and Lạng Sơn provinces and became known as the Nùng. Barlow (2005) suggests that many of the original 11th-century rebels who fled to Vietnam were absorbed by the related Tày peoples of the region.[37]

The Nùng, although lacking a leader of the stature of Nùng Trí Cao, rose up in 1352, 1430, 1434[37] and many other unrecorded rebellions.

In the 16th century the Zhuang, principally from Guangxi and perhaps from southeast Yunnan, began migrating into Vietnam. This movement was quickened by the acceleration of the cycle of disasters, and by the political events of the seventeenth century which brought larger numbers of Chinese immigrants into the region, such as the fall of the Ming, the rebellion of Wu Sangui, the Qing occupation, and the Muslim revolts in Yunnan.[37] This migration was a peaceful one which occurred family by family.[37] French administrators later identified a number of Nùng clans in the course of their ethnographic surveys.[37] These had incorporated Chinese place names in their clan names and hence indicate the place of their origin in China, such as the "Nùng Inh" clan, from Long Ying in the southwest of Guangxi.[37] Such other names as can be correlated with locations indicate that the migrants were primarily from the immediate frontier region of the southwest of Guangxi.[37] The Nùng became increasingly numerous in the region, and were spread out through a long stretch of the Vietnamese northern border from Lạng Sơn to Cao Bằng, and about That Khe.[37] The Mạc dynasty, a Vietnamese dynasty ruled over the Vietnamese northeast highlands, profited from the migration in that they were able to draw upon Nùng manpower for their own forces.[37]

In 1833, Nông Văn Vân, a Nùng chieftain, led a rebellion against Vietnamese rule. He quickly took control of Cao Bằng, Tuyên Quang, Thái Nguyên and Lạng Sơn provinces, aiming to create a separate Tày-Nùng state in the northern region of Vietnam. His rising was eventually suppressed by the Nguyễn dynasty in 1835.

In the 1860s, the Nùng sided with Sioung (Xiong), a self-proclaimed Hmong king. Sioung's armies raided gold from Buddhist temples and seized large tracts of land from other people.[38]

The period from the Taiping Rebellion (1850–64) to the early twentieth century was marked by continual waves of immigration by Zhuang/Nùng peoples from China into Vietnam.[37] These waves were a result of the continuous drought of Guangxi which made the thinly occupied lands of northern Vietnam an attractive alternative habitation. The immigration process was generally a peaceful one as the Nùng purchased land from the "Tho" owners.[37] The Nùng were superior to the Tho in cultivating wet rice and transformed poor lands, facilitating later migrations into adjoining areas.[37] The repeated violent incursions of the Taiping era and the Black Flag occupation accelerated the outflow of Tho as the bands from China were largely Zhuang who favored the Nùng at the expense of the Tho.[37] The Tho who remained became alienated from the Vietnamese government which could not offer protection and became clients of the Chinese and the Nùng.[37]

The Nùng dominance became so pronounced that when Sun Yat-sen wished to raise fighters in the region, he could recruit them from Nùng villages such as Na Cen and Na Mo, both on the Vietnamese side of the border.[37] The French colonists saw this Nùng predominance as a threat, and found it convenient at that time to re-assert the primacy of the Vietnamese administrative system in the region.[37]

The French, however, perhaps having less choice, tended to support the Tho and other minorities, often undifferentiated as "Man" in their reports—usually a reference to Yao—as a counterweight against the Nùng.[37] In 1908, for example, following an incident in which Sun Yat-sen's mercenary Nung warriors had killed several French officers, the French offered a bounty of eight dollars for each head brought in by the "Man".[37] The bounty was paid 150 times.[37]

The French colonial government took advantage of ancient tensions between the highland ethnic groups and the Kinh majority in Vietnam. In the northwest mountains, they set up a semi-autonomous minority federation called Sip Song Chau Tai (French: Pays Taï), complete with armed militias and border guards.[39] When war broke out in 1946, groups of Thai, H’mong and Muong in the northwest sided with the French and against the Vietnamese and even provided battalions to fight with the French troops.[39] But The Nùng and Tày supported the Viet Minh and provided the Vietnamese leader, Ho Chi Minh, with a safe base for his guerrilla armies.[40] After defeating the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, the Viet Minh tried to win the allegiance of all of the northern ethnic minorities by creating two autonomous zones, Thai–Meo Autonomous Zone and Viet Bac Autonomous Zone respectively, allowing limited self-government within a “unified multi-national state”.[39] During the Vietnam War, many Nùng fought alongside the North Vietnamese Army (NVA).[39]

After the Unification of Vietnam in 1975, Viet Bac Autonomous Zone in which the Nùng and Tày were most numerous was revoked by Lê Duẩn. the new government pursued a policy of forced assimilation of the minorities into the Vietnamese culture.[39] All education was conducted in the Vietnamese language, traditional customs were discouraged or outlawed, and minority people were moved from their villages into government settlements.[39] At the same time the government created “New Economic Zones” along the Chinese border and in the Central Highlands. Frequently this involved taking the best land in order to resettle thousands of people from the overcrowded lowlands.[39] During the 1980s, an estimated 250,000 ethic Vietnamese were settled in the mountainous regions along the Chinese border, leading to a shortage of food in the region and much suffering.[40]

As tension arose between Vietnam and China in 1975, Hanoi feared the loyalty of the Nùng and the Chinese-Vietnamese,[41] concerning that they would side with China. This comes from the fact that many of the Nùng just migrated into the Vietnamese border side and many of their relatives still lived in the other side of the border.

In the 1990s, the Doi Moi program brought a shift in policy, including the creation of a government department responsible for minority affairs. Many of the changes and the liberalization that preserving the heritage of the Nung and other ethnic groups has a great appeal to tourists a source of significant income for Vietnam. Nonetheless, in many areas the minorities’ traditional lifestyles are fast being eroded.[40]

With the territorial disputes between Vietnam and China in recent years, the ethnic minorities living in the borderland, including the Nùng, have been under the watchful eye of the Vietnamese government.

Description

The Nùng support themselves through agriculture, such as farming on terraced hillsides, tending rice paddies, and growing orchard products. They produce rice, maize, tangerines, persimmons and anise. They are also known for their handicrafts, making items from bamboo and rattan, as well as weaving. They engage in carpentry and iron forging also.

Prominent Nùng persons include Kim Đồng of the August Revolution in 1945.

Language

The Nùng language is part of the Tai language family; its written script was developed around the 17th century. It is close to the Zhuang language.

Religion

Many Nùng practice an indigenous religion with animistic, totemic and shamanic features similarly to other Tai ethnic groups.[2] Others have adopted Buddhism.

Customs

When drinking alcohol, partakers cross hands and drink from the opposite glass to demonstrate trust. Fairy tales, folk music, and adherence to tradition and ethnic identity are strong characteristics of Nùng people.

The Nùng's traditional indigo clothing, symbolising faithfulness, was made famous by Hồ Chí Minh, worn when he returned to Vietnam in 1941.

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ GSO 2010, p. 134.

- 1 2 Nguyễn 2009.

- ↑ Wilson & Vy 1976, p. 11.

- ↑ Hoàng Nam 2008, p. 11.

- ↑ Blench 2017, p. 11.

- ↑ Ostapirat 2013, pp. 1-10.

- ↑ Sagart 2008, pp. 146-152.

- ↑ Sagart 2008, p. 151.

- 1 2 3 4 Sagart et al. 2017, p. 188.

- ↑ Sagart et al. 2017, p. 189.

- ↑ Ko 2014, pp. 426–436.

- ↑ Wei et al. 2017, pp. 1-12.

- ↑ McColl 2018, pp. 1-28.

- ↑ Brindley 2015, p. 51.

- ↑ Chamberlain 2016, p. 41.

- ↑ Behr 2017, p. 12.

- ↑ Behr 2009, p. 23.

- 1 2 Behr 2009, p. 24.

- ↑ Behr 2009, p. 34.

- ↑ Behr 2009, p. 36.

- ↑ Behr 2009, p. 37.

- ↑ Behr 2009, p. 40.

- ↑ Behr 2009, p. 41.

- 1 2 Holm 2013, p. 785.

- 1 2 Edmondson 2007, p. 16.

- ↑ Zhengzhang 1991, pp. 159–168.

- ↑ Holm 2013, pp. 784-785.

- ↑ Edmondson 2007, p. 17.

- ↑ Sagart 2008, p. 143.

- 1 2 Li 2001, p. 15.

- ↑ Li 2001, p. 19.

- ↑ Behr 2002, pp. 1-2.

- 1 2 Behr 2002, p. 2.

- ↑ Behr 2002, pp. 2-3.

- ↑ Behr 2002, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 Chamberlain 2016, pp. 27-77.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Barlow 2005.

- ↑ "Nung". The Peoples of Vietnam (PDF). Asia Harvest USA.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Nung". InfoMekong.com. 2013.

- 1 2 3 Minahan 2012.

- ↑ Hoover 2010, p. 6.

Sources

- Barlow, Jeffrey (2005). "The Zhuang: A Longitudinal Study of Their History and Their Culture". Pacific University. Archived from the original on 2007-02-06.

- Behr, Wolfgang (2017). "The language of the bronze inscriptions". In Shaughnessy, Edward L. Kinship: Studies of Recently Discovered Bronze Inscritpions from Ancient China. The Chinese University Press of Hong Kong. pp. 9–32. ISBN 978-9-629-96639-3.

- ——— (2009). "Dialects, diachrony, diglossia or all three? Tomb text glimpses into the language(s) of Chǔ". TTW-3, Zürich, 26.-29.VI.2009, “Genius loci”: 1–48.

- ——— (2006). "Some Chŭ 楚 words in early Chinese literature". EACL-4, Budapest: 1–21.

- ——— (2002). "Stray loanword gleanings from two Ancient Chinese fictional texts". 16e Journées de linguistique d'Asie Orientale, Centre de Recherches Linguistiques sur l’Asie Orientale (E.H.E.S.S.), Paris: 1–6.

- Blench, Roger (2017) [2015]. "Origins of Ethnolinguistic Identity in Southeast Asia" (PDF). In Habu, Junko; Lape, Peter; Olsen, John. Handbook of East and Southeast Asian Archaeology. Springer. ISBN 978-1-493-96521-2.

- Blust, Robert (1996). "Beyond the Austronesian Homeland: The Austric Hypothesis and Its Implications for Archaeology". In Goodenough, Ward H. Prehistoric Settlement of the Pacific, Volume 86, Part 5. American Philosophical Society. pp. 117–158. ISBN 978-0-871-69865-0.

- Brindley, Erica F. (2015). Ancient China and the Yue. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-08478-0.

- Brown, Michael Edward; Ganguly, Sumit (2003). Fighting Words: Language Policy and Ethnic Relations in Asia. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-52333-2.

- Chamberlain, James R. (2016). "Kra-Dai and the Proto-History of South China and Vietnam". Journal of the Siam Society, Vol. 104: 27–77.

- Edmondson, Jerold A. (2007). "The power of language over the past: Tai settlement and Tai linguistics in southern China and northern Vietnam" (PDF). Studies in Southeast Asian languages and linguistics, Jimmy G. Harris, Somsonge Burusphat and James E. Harris, ed. Bangkok, Thailand: Ek Phim Thai Co. Ltd.: 1–25.

- GSO (June 2010). "The 2009 Vietnam Population and Housing Census: Completed Results". General Statistics Office of Vietnam. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- Hoàng Nam (2008). The Nùng ethnic group of Việt Nam. Hanoi: Thế Giới Publishers.

- Holm, David (2014). "A Layer of Old Chinese Readings in the Traditional Zhuang Script". Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities: 1–45.

- ——— (2013). Mapping the Old Zhuang Character Script: A Vernacular Writing System from Southern China. BRILL. ISBN 978-9-004-22369-1.

- Hoover, Daniel J. (2010). "The migration of Chinese-Vietnamese from Vietnam : the Truong Family". Department of History, Baylor University.

- Johnson, Eric C. (September 2010). In cooperation with Mingfu Wang (王明富). "A Sociolinguistic Introduction to the Central Taic Languages of Wenshan Prefecture, China" (PDF). SIL Electronic Survey Report. SIL International (2010–027).

- Ko, Albert Min-Shan; et al. (2014). "Early Austronesians: Into and Out Of Taiwan" (PDF). The American Journal of Human Genetics. 94: 426–436.

- Li, Hui (2001). "Daic Background Vocabulary in Shanghai Maqiao Dialect" (PDF). Proceedings for Conference of Minority Cultures in Hainan and Taiwan, Haikou: Research Society for Chinese National History: 15–26.

- McColl, Hugh; et al. (2018). "Ancient Genomics Reveals Four Prehistoric Migration Waves into Southeast Asia". bioRxiv: 1–28. bioRxiv 278374.

- Minahan, James B. (2012-08-30). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO.

- Nguyễn, Thị Yên (2009). Tày-Nùng Folk Beliefs. Hanoi: Social Sciences Publishing House. Vb 47561.

- Ostapirat, Weera (2013). "Austro-Tai revisited" (PDF). Plenary session 2: Going beyond history: reassessing genetic grouping in SEA The 23rd Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, May 29–31, 2013, Chulalongkorn University: 1–10.

- Sagart, Laurent; Hsu, Tze-Fu; Tsai, Yuan-Ching; Hsing, Yue-Ie C. (2017). "Austronesian and Chinese words for the millets". Language Dynamics and Change: 187–209.

- Sagart, Laurent (2008). "The expansion of Setaria farmers in East Asia". In Sanchez-Mazas, Alicia; Blench, Roger; Ross, Malcolm D.; Peiros, Ilia; Lin, Marie. Past Human Migrations in East Asia: Matching Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics (Routledge Studies in the Early History of Asia) 1st Edition. Routledge. pp. 133–157. ISBN 978-0-415-39923-4.

- ——— (2005). "Sino-Tibetan-Austronesian: An updated and improved argument". In Sagart, Laurent; Sanchez-Mazas, Alicia; Blench, Roger. The Peopling of East Asia: Putting Together Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics. RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 161–176. ISBN 978-0-415-32242-3.

- ——— (1994). "Proto-Austronesian and Old Chinese Evidence for Sino-Austronesian". Oceanic Linguistics Vol. 33, No. 2: 271–308.

- ——— (1993). "Chinese and Austronesian: Evidence for a genetic relationship". Journal of Chinese Linguistics Vol. 21, No. 1: 1–63.

- van Driem, George (2017). "The domestications and the domesticators of Asian rice" (PDF). In Robbeets, Martine; Savelyev, Alexander. Language Dispersal Beyond Farming. John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 183–214. ISBN 978-9-027-26464-0.

- ——— (2005). "Sino-Austronesian vs. Sino-Caucasian, Sino-Bodic vs. Sino-Tibetan, and Tibeto-Burman as default theory" (PDF). In Yadava, Yogendra Prasada; Bhattarai, Govinda; Lohani, Ram Raj; Prasain, Balaram; Parajuli, Krishna. Contemporary Issues in Nepalese Linguistics. Linguistic Society of Nepal. pp. 285–338. ISBN 978-9-994-65769-8.

- Wei, Lan-Hai; Yan, Shi; Teo, Yik-Ying; Huang, Yun-Zhi; et al. (2017). "Phylogeography of Y-chromosome haplogroup O3a2b2-N6 reveals patrilineal traces of Austronesian populations on the eastern coastal regions of Asia". PLOS One: 1–12.

- Wilson, Nancy F.; Vy, Thị Bé (1976). Sẹc mạhn slú Nohng Fạn Slihng = Ngũ-vụng Nùng Phạn Slinh = Nung Fan Slihng vocabulary: Nung-Viêt-English (PDF). Summer Institute of Linguistics.

- Zhengzhang, Shangfang (1991). "Decipherment of Yue-Ren-Ge (Song of the Yue boatman)". Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale. 20 (2): 159–168.

Further reading

- Đoàn, Thiện Thuật. Tay-Nung Language in the North Vietnam. [Tokyo?]: Instttute [sic] for the Study of Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, 1996.