Yue (state)

| State of Yue 越國 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ?–334 BC | |||||||||||||

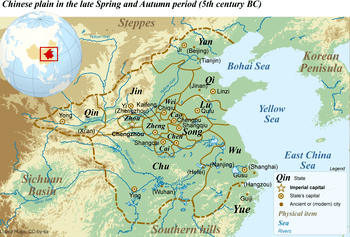

Map of the Chinese plain in the 5th century BC. The state of Yue is located in the southeast corner. | |||||||||||||

| Status | Kingdom | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Kuaiji, later Wu | ||||||||||||

| Common languages |

pre-/proto-Austronesian, proto-Tai-Kadai | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Animism | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||

| Historical era |

Spring and Autumn period Warring States period | ||||||||||||

• Established | ? | ||||||||||||

• Conquered by Chu | 334 BC | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Yue | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png) "Yue" in seal script (top) and modern (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 越 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Yue (Chinese: 越國; Old Chinese: *[ɢ]ʷat), also known as Yuyue, was a state in ancient China which existed during the first millennium BC – the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods of China's Zhou dynasty – in the modern provinces of Zhejiang, Shanghai, and Jiangsu. Its original capital was a site near Mount Kuaiji (around modern Shaoxing); after its conquest of Wu, the Kings of Yue moved their court north to the city of Wu (modern Suzhou).

History

The name "Baiyue" (百越) was applied indiscriminately to many non-Chinese peoples who had been mentioned in numerous classical texts. A specific kingdom, which had been known as the "Yue Guo" (越國) in modern Zhejiang, was not mentioned until it began a series of wars against its northern Yue neighbor Wu during the late 6th century BCE.

With help from Wu's enemy Chu, Yue was able to be victorious after several decades of conflict. The famous Yue King Goujian destroyed and annexed Wu in 473 BCE. Competing against the fewer, more powerful Warring States, Yue did not fare as well. During the reign of Wujiang (無彊), six generations after Goujian, Yue was destroyed and annexed by Chu in 334 BCE.

During its existence, Yue was famous for the quality of its metalworking, particularly its swords. Examples include the extremely well-preserved Swords of Goujian and Zhougou.

The Yue state appears to have been a largely indigenous political development in the lower Yangtze. This region corresponds with that of the old corded-ware Neolithic, and it continued to be one that shared a number of practices, such as tooth extraction, pile building, and cliff burial, practices that continued until relatively recent times in places such as Taiwan. Austronesian speakers also still lived in the region down to its conquest and sinification beginning about 240 B.C.[1]

What set the Yue apart from other Sinitic states of the time was their possession of a navy.[2] Yue culture was distinct from the Chinese in its practice of naming boats and swords.[3] A Chinese text described the Yue as a people who used boats as their carriages and oars as their horses.[4]

Rulers of Yue family tree

[5] Their ancestral name is rendered variously as either Si (姒) or Luo (雒).[6]

| Rulers of Yue family tree | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Aftermath

After the fall of Yue, the ruling family moved south to what is now northern Fujian and set up the Minyue kingdom. This successor state lasted until around 150 BC, when it miscalculated an alliance with the Han dynasty.

Mingdi, Wujiang's second son, was appointed minister of Wucheng (present-day Huzhou's Wuxing District) by the king of Chu. He was titled Marquis of Ouyang Ting, from a pavilion on the south side of Ouyu Mountain. The first Qin dynasty emperor Qin Shi Huang abolished the title after his conquest of Chu in 223 BC, but descendants and subjects of its former rulers took up the surnames Ou, Ouyang, and Ouhou (歐侯) in remembrance.

Astronomy

In Chinese astronomy, there are two stars named for Yue:

- Yue (along with Wu) is represented by the star Zeta Aquilae in the "Left Wall" of the Heavenly Market enclosure[7][8]

- Yue is also represented by the star Psi Capricorni or 19 Capricorni[9] in the "Twelve States" of the mansion of the Girl.[10]

People from Yue

- Yuenü, swordswoman & author of the earliest-known exposition on swordplay[11]

- Xi Shi, a famous beauty of the ancient Yue Guo.

Language

Possible languages spoken in the state of Yue may have been of Tai-Kadai and Austronesian origins. Li Hui (2001) identifies 126 Tai-Kadai cognates in Maqiao Wu dialect spoken in the suburbs of Shanghai out of more than a thousand lexical items surveyed.[12] According to the author, these cognates are likely traces of 'old Yue language' (gu Yueyu 古越語).[12]

Wolfgang Behr (2002) points out that some scattered non-Sinitic words found in the two ancient Chinese fictional texts, Mu tianzi zhuan 穆天子傳 (4th c. B.C.) and Yuejue shu 越絕書 (1st c. A.D.)[lower-alpha 1], can be compared to lexical items in Tai-Kadai languages:

- "吳謂善「伊」, 謂稻道「缓」, 號從中國, 名從主人。"[13]

“The Wú say yī for ‘good’ and huăn for ‘way’, i.e. in their titles they follow the central kingdoms, but in their names they follow their own lords.”

伊 yī < MC ʔjij < OC *bq(l)ij ← Siamese diiA1, Longzhou dai1, Bo'ai nii1 Daiya li1, Sipsongpanna di1, Dehong li6 < proto-Tai *ʔdɛiA1 | Sui ʔdaai1, Kam laai1, Maonan ʔdaai1, Mak ʔdaai6 < proto-Kam-Sui/proto-Kam-Tai *ʔdaai1 'good'

缓 [huăn] < MC hwanX < OC *awan ← Siamese honA1, Bo'ai hɔn1, Dioi thon1 < proto-Tai *xronA1| Sui khwən1-i, Kam khwən1, Maonan khun1-i, Mulam khwən1-i < proto-Kam-Sui *khwən1 'road, way' | proto-Hlai *kuun1 || proto-Austronesian *Zalan (Thurgood 1994:353)

- yuè jué shū 越絕書 (The Book of Yuè Records), 1st c. A.D.[14]

絕 jué < MC dzjwet < OC *bdzot ← Siamese codD1 'to record, mark' (Zhengzhang Shangfang 1999:8)

- "姑中山者越銅官之山也, 越人謂之銅, 「姑[沽]瀆」。"[14]

“The Middle mountains of Gū are the mountains of the Yuè’s bronze office, the Yuè people call them ‘Bronze gū[gū]dú.”

「姑[沽]瀆」 gūdú < MC ku=duwk < OC *aka=alok

← Siamese kʰauA1 'horn', Daiya xau5, Sipsongpanna xau1, Dehong xau1, Lü xău1, Dioi kaou1 'mountain, hill' < proto-Tai *kʰauA2; Siamese luukD2l 'classifier for mountains', Siamese kʰauA1-luukD2l 'mountain' || cf. OC 谷 gǔ < kuwk << *ak-lok/luwk < *akə-lok/yowk < *blok 'valley'

- "越人謂船爲「須盧」。"[15]

"... The Yuè people call a boat xūlú. (‘beard’ & ‘cottage’)"

? ← Siamese saʔ 'noun prefix'

← Siamese rɯaA2, Longzhou lɯɯ2, Bo'ai luu2, Daiya hə2, Dehong hə2 'boat' < proto-Tai *drɯ[a,o] | Sui lwa1/ʔda1, Kam lo1/lwa1, Be zoa < proto-Kam-Sui *s-lwa(n)A1 'boat'

- "[劉]賈築吳市西城, 名曰「定錯」城。"[16]

"[Líu] Jiă (the king of Jīng 荆) built the western wall, it was called dìngcuò ['settle(d)' & 'grindstone'] wall."

定 dìng < MC dengH < OC *adeng-s

← Siamese diaaŋA1, Daiya tʂhəŋ2, Sipsongpanna tseŋ2 'wall'

? ← Siamese tokD1s 'to set→sunset→west' (tawan-tok 'sun-set' = 'west'); Longzhou tuk7, Bo'ai tɔk7, Daiya tok7, Sipsongpanna tok7 < proto-Tai *tokD1s ǀ Sui tok7, Mak tok7, Maonan tɔk < proto-Kam-Sui *tɔkD1

See also

Notes

- ↑ The author notes that these two texts are only preserved in corrupt versions and share a rather convoluted editorial history.

References

- ↑ Goodenough, Ward Hunt (1996). Prehistoric Settlement of the Pacific, Volume 86, Part 5. American philosophical society. p. 48. ISBN 9780871698650.

- ↑ Holm 2014, p. 35.

- ↑ Kiernan 2017, pp. 49-50.

- ↑ Kiernan 2017, p. 50.

- ↑ Theobald, Ulrich. China Knowledge. "Chinese History – Yue 越 (Zhou period feudal state)". 2000. Accessed 5 December 2013.

- ↑ Chinese Text Project. Wu–Yue Chunqiu. 《越王無余外傳》 ["Yuèwàng Wúyú Wàizhuàn"]. Accessed 5 December 2013.(in Chinese)

- ↑ "AEEA (Activities of Exhibition and Education in Astronomy) 天文教育資訊網". 23 Jul 2006. (in Chinese)

- ↑ Allen, Richard. "Star Names – Their Lore and Meaning: Aquila".

- ↑ Ian Ridpath's Startales - Capricornus the Sea Goat

- ↑ Allen, Richard. "Star Names – Their Lore and Meaning: Capricornus".

- ↑ Hong Lee and Stefanowsky (2007). Biographical dictionary of Chinese women: antiquity through Sui, 1600 B.C.E.-618 C.E. M.E. Sharpe. p. 91.

- 1 2 Li 2001, p. 15.

- ↑ Behr 2002, pp. 1-2.

- 1 2 Behr 2002, p. 2.

- ↑ Behr 2002, pp. 2-3.

- ↑ Behr 2002, p. 3.

Sources

- Behr, Wolfgang (2002). "Stray loanword gleanings from two Ancient Chinese fictional texts". 16e Journées de linguistique d'Asie Orientale, Centre de Recherches Linguistiques sur l’Asie Orientale (E.H.E.S.S.), Paris: 1–6.

- Holm, David (2014). "A Layer of Old Chinese Readings in the Traditional Zhuang Script". Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities: 1–45.

- Kiernan, Ben (2017), Việt Nam: A History from Earliest Times to the Present, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-195-16076-5.

- Li, Hui (2001). "Daic Background Vocabulary in Shanghai Maqiao Dialect" (PDF). Proceedings for Conference of Minority Cultures in Hainan and Taiwan, Haikou: Research Society for Chinese National History: 15–26.

Further reading

- Zhengzhang Shangfang 1999. "An Interpretation of the Old Yue Language Written in Goujiàn's Wéijiă lìng" [句践“维甲”令中之古越语的解读]. In Minzu Yuwen 4, pp. 1-14.

- Zhengzhang Shangfang 1998. “Gu Yueyu” 古越語 [The old Yue language]. In Dong Chuping 董楚平 et al. Wu Yue wenhua zhi 吳越文化誌 [Record of the cultures of Wu and Yue]. Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe, 1998, vol. 1, pp. 253–281.

- Zhengzhang Shangfang 1990. "Some Kam-Tai Words in Place Names of the Ancient Wu and Yue States" [古吴越地名中的侗台语成份]. In Minzu Yuwen 6.

External links

- Eric Henry: The Submerged History of Yuè (Sino-Platonic Papers 176, May 2007)