Form criticism

Form criticism as a method of biblical criticism classifies units of scripture by literary pattern and then attempts to trace each type to its period of oral transmission.[1] Form criticism seeks to determine a unit's original form and the historical context of the literary tradition.[1]

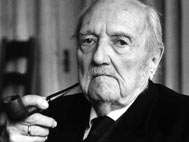

Hermann Gunkel (1862-1932), Martin Noth, Gerhard von Rad, and other scholars originally developed form criticism for Old Testament studies; they used it to supplement the documentary hypothesis with reference to its oral foundations.[2] Karl Ludwig Schmidt, Martin Dibelius (1883-1947) and Rudolf Bultmann later applied form criticism to the Gospels.

Over the past few decades, form criticism's emphasis on oral tradition has waned in Old Testament studies. This is largely because scholars are increasingly skeptical about our ability to distinguish the "original" oral traditions from the literary sources that preserve them. As a result, the method as applied to the Old Testament now focuses on the Bible's literary genres, becoming virtually synonymous with genre criticism.

Literary forms and sociological contexts

Form criticism begins by identifying a text's genre or conventional literary form, such as parables, proverbs, epistles, or love poems. It goes on to seek the sociological setting for each text's genre, its "situation in life" (German: Sitz im Leben). For example, the sociological setting of a law is a court, or the sociological setting of a psalm of praise (hymn) is a worship context, or that of a proverb might be a father-to-son admonition. Having identified and analyzed the text's genre-pericopes, form criticism goes on to ask how these smaller genre-pericopes contribute to the purpose of the text as a whole.

Demythologising

As developed by Rudolf Bultmann (1884–1976) and others, form criticism attempts to rediscover the original kernel of meaning of a text. Bultmann described this process as "demythologising", although the word must be used with caution. "Myth" is not intended to convey a sense of "untrue", but the significance of an event in the narrator's agenda[3]. What, ultimately, does the writer mean by it?

In the case of the Canonical gospels, this demythologising aims to reveal the underlying kerygma or "message" conveyed by a passage: what does a Gospel say about the nature and significance of Christ and about his teaching? Form criticism thus attempts to reconstruct the theological opinions of the primitive church and of pre-talmudic Judaism.

The Evangelists

Studies based on form criticism state that the Evangelists drew upon oral traditions when composing the canonical gospels. This oral tradition consisted of several distinct components. Parables and aphorisms are the "bedrock of the tradition." Pronouncement stories, scenes that culminate with a saying of Jesus, are more plausible historically than other kinds of stories about Jesus. Other sorts of stories include controversy stories, in which Jesus is in conflict with religious authorities; miracles stories, including healings, exorcisms, and nature wonders; call and commissioning stories; and legends.[4][5][6] The oral model developed by the form critics drew heavily on contemporary theory of Jewish folkloric transmission of oral material, and as a result of this form criticism one can trace the development of the early gospel tradition.[7] However, "Today it is no exaggeration to claim that a whole spectrum of main assumptions underlying Bultmann's Synoptic Tradition must be considered suspect."[8]

See also

References

- 1 2 "form criticism." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2 Dec. 2007 read online

- ↑ Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ↑ Herrin, Paul, Smoking the Tree of Knowledge. Johnson City: East Tennessee State University. 2013 https://soundcloud.com/paul-herrin/smoking-the-tree-of-knowledge

- ↑ Schmidt, K. L. (1919). Der Rahmen der Geschichte Jesu. Berlin: Paternoster.

- ↑ Dibelius, M. (1919). Die Formgeschichte des Evangelium 3d Ed. Günter Bornkamm (ed). Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr.

- ↑ Bultmann, R. (1921). Die Geschichte der synoptischen Tradition. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

- ↑ http://www.biblicalstudies.org.uk/article_tradition_bailey.html

- ↑ Kelber, W. H. (1997). The Oral and Written Gospel: The Hermeneutics of Speaking and Writing in the Synoptic Tradition, Mark, Paul, and Q. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 8.

Bibliography

- Armerding, Carl E. The Old Testament and Criticism. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1983, pp. 43–66.

- Hayes, John H. An Introduction to Old Testament Study. Nashville: Abingdon, 1979, pp. 121–154.

- Hayes, John H., ed. Old Testament Form Criticism. San Antonio: Trinity University, 1974.

- McKnight, E.V., "What is Form Criticism?" Guide to Biblical Scholarship, New Testament; Philadelphia, 1967.

- Tucker, Gene M. Form Criticism of the Old Testament. Guides to Biblical Scholarship. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1971.

- Tucker, Gene M."Form Criticism, OT," pp. 342–345 in Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible, Supplementary Volume. Keith Crim, gen. ed. Nashville: Abingdon, 1976.

Further reading

- Koch, Klaus (1969). The Growth of the Biblical Tradition: The Form-Critical Method. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0-684-14524-3.

- Lohfink, Gerhard (1979). The Bible: Now I Get It! A Form-Critical Handbook. New York: Doubleday.

- Tucker, Gene M. (1971). Form Criticism of the Old Testament. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. ISBN 0-8006-0177-7.

External links

- Form criticism, Dictionary.com

- Form criticism, Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- Biblical criticism, at Religious Tolerance web site.