Eurasian lynx

The Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) is a medium-sized wild cat occurring from Northern, Central and Eastern Europe to Central Asia and Siberia, the Tibetan Plateau and the Himalayas. It inhabits temperate and boreal forests up to an altitude of 5,500 m (18,000 ft). Because of its wide distribution, it has been listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List since 2008. It is threatened by habitat loss and fragmentation, poaching and depletion of prey. The European lynx population is estimated at comprising maximum 10,000 individuals and is considered stable.[1]

| Eurasian lynx | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Felinae |

| Genus: | Lynx |

| Species: | L. lynx[2] |

| Binomial name | |

| Lynx lynx[2] | |

| |

| Distribution of Eurasian lynx, 2015[1] | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy

Felis lynx was the scientific name used in 1758 by Carl Linnaeus in his work Systema Naturae.[3] In the 19th and 20th centuries, the following Eurasian lynx subspecies were proposed:[4][5]

- Northern lynx (L. l. lynx) Linnaeus, 1758: Fennoscandia, Baltic states, Poland, Belarus, European part of eastern, western, northern, central part of Russia, Ural Mountains, Western Siberia east to the Yenisei river[1]

- Turkestan lynx (L. l. isabellinus) Blyth, 1847: Central Asia

- Caucasian lynx (L. l. dinniki) Satunin, 1915: Caucasus

- Siberian lynx (L. l. wrangeli) Ognew, 1928: Eastern Siberia

- Balkan lynx (L. l. balcanicus) Bures, 1941: Balkans

- Carpathian lynx (L. l. carpathicus) Kratochvil & Stollmann, 1963: Carpathian Mountains, Central Europe

The following subspecies were also described, but are now not considered valid:[5]

- Altai lynx (L. l. wardi) Lydekker, 1904: Altai Mountains

- Baikal lynx (L. l. kozlovi) Fetisov, 1950: Central Siberia

- Amur lynx (L. l. stroganovi) Heptner, 1969: Amur region

The Sardinian lynx (L. l. sardiniae) Mola, 1908 was a misidentified Sardinian wild cat.[5]

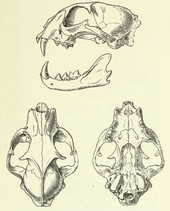

Characteristics

The Eurasian lynx has a relatively short, reddish or brown coat, which tends to be more brightly coloured in animals living at the southern end of its range. In winter, however, this is replaced by a much thicker coat of silky fur that varies from silver-grey to greyish brown. The underparts of the animal, including the neck and chin, are white at all times of the year. The fur is almost always marked with black spots, although the number and pattern of these are highly variable. Some animals also possess dark brown stripes on the forehead and back. Although spots tend to be more numerous in animals from southern populations, Eurasian lynx with heavily spotted fur may exist close to others with plain fur. It has powerful, relatively long legs, with large webbed and furred paws that act like snowshoes. It also possesses a short "bobbed" tail with an all-black tip, black tufts of hair on its ears, and a long grey-and-white ruff. It is the largest of the four lynx species, ranging in length from 80 to 130 cm (31 to 51 in) and standing 60–75 cm (24–30 in) at the shoulder. The tail measures 11 to 24.5 cm (4.3 to 9.6 in) in length.[6] On average, males weigh 21 kg (46 lb) and females weigh 18 kg (40 lb).[7] Male lynxes from Siberia, where the species reaches the largest body size, can weigh up to 38 kg (84 lb) or reportedly even 45 kg (99 lb).[8] The race from the Carpathian Mountains can also grow quite large and rival those from Siberia in body mass in some cases.[9]

Distribution and habitat

The Eurasian lynx inhabits rugged country providing plenty of hideouts and stalking opportunities. Depending on the locality, this may include rocky-steppe, mixed forest-steppe, boreal forest, and montane forest ecosystems. In the more mountainous parts of its range, Eurasian lynx descends to the lowlands in winter, following prey species and avoiding deep snow. It tends to be less common where grey wolf is abundant, and wolves have been reported to attack and even eat lynx.[6]

Europe

The Eurasian lynx was once quite common in most of continental Europe. By the early 19th century, it was persecuted to local extinction in western and southern European lowlands, but survived only in mountainous areas and Scandinavian forests. By the 1950s, it had become extinct in most of Western and Central Europe, where only scattered and isolated populations exist today.[9]

Scandinavia

The Eurasian lynx was close to extinction in Scandinavia in the 1930s. Since the 1950s, the population slowly recovered and forms three subpopulations in northern, central and southern Scandinavia.[10] In Norway, the Eurasian lynx was subjected to an official bounty between 1846 and 1980 and could be hunted without license. In 1994, a compensation scheme for livestock killed by lynx was introduced. By 1996, the lynx population was estimated to comprise 410 Individuals, decreased to less than 260 individuals in 2004 and increased since 2005 to about 452 mature individuals by 2008.[11] In Sweden, the lynx population was estimated at about 1,400 individuals in 2006 and 1,250 in 2011. Hunting is controlled by government agencies.[12] In Finland, about 2,200–2,300 individuals were present according to a 2009 estimate.[13] Lynx population in Finland have been increasing every year since 1991, and is estimated to be nowadays larger than ever before. Limited hunting is permitted. In 2009 the Finnish Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry gave a permit for hunting of 340 lynx individuals.[14]

Western Europe

The Eurasian lynx was exterminated in the French Alps in the early 20th century. Following reintroduction of lynx in Swiss Jura Mountains in the 1970s, lynx were recorded again in the French Alps and Jura from the late 1970s onwards.[15] It recolonised the Italian Alps since the 1980s, also from reintroduced populations in Switzerland, Austria and Slovenia.[16] By 2010, the Alpine lynx population comprised about 120–150 individuals ranging over 27,800 km2 (10,700 sq mi) in six sub-areas.[17] In the Netherlands, lynx were sighted sporadically since 1985 in the country's southern part.[18]

In Germany, the Eurasian lynx was exterminated in Germany in 1850. It was reintroduced to the Bavarian Forest and the Harz in the 1990s; other areas were populated by lynx immigrating from neighboring France and the Czech Republic. In 2002 the first birth of wild lynx on German territory was announced, following a litter from a pair of lynx in the Harz National Park. Small populations exist also in Saxon Switzerland, Palatinate Forest, and Fichtelgebirge. Eurasian lynx also migrated to Austria, where they had also been exterminated. An episode of the PBS television series Nature featured the return of the lynx to Austria's Kalkalpen National Park after a 150-year absence.[19] A higher proportion are killed by human causes than by infectious diseases.[20] In the United Kingdom, the Eurasian lynx is extirpated since the Middle Ages. It was proposed to reintroduce the species to the Scottish Highlands.[21][22]

Eastern Europe

- Carpathian Mountains: About 2,800 Eurasian lynx live in this mountain range in the Czech Republic, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Hungary.[23] It is the largest contiguous Eurasian Lynx population west of the Russian border.

- Czech Republic: In Bohemia, the Eurasian lynx was exterminated in the 19th century (1830–1890) and in Moravia probably at the turn of the 20th century. After 1945, migration from Slovakia created a small and unstable population in Moravia. In the 1980s, almost 20 specimens were imported from Slovakia and reintroduced in the Šumava area. In early 2006, the population of lynx in the Czech Republic was estimated at 65–105 individuals. Hunting is prohibited, but the lynx is often threatened by poachers.

- Poland: In its Environment and Environmental Protection Section, the 2011 Central Statistical Office Report puts the number of Eurasian lynxes observed in the wild in Poland as of 2010 at approximately 285.[24] There are two major populations of lynxes in Poland, one in the northeastern part of the country (most notably in the Białowieża Forest) and the other in the southeastern part in the Carpathian Mountains. Since the 1980s, lynxes have also been spotted in the region of Roztocze, Solska Forest, Polesie Lubelskie, and Karkonosze Mountains, though they still remain rare in those areas. A successfully reintroducted population of lynxes has also been living in the Kampinos National Park since the 1990s.

- Slovakia: the Eurasian lynx inhabits deciduous, coniferous and mixed forests at elevations of 180–1,592 m (591–5,223 ft), mostly in national parks and other protected areas; its presence has been positively confirmed in more than half of Slovak territory (2012).[25] In terms of absolute numbers though in Štiavnica Mountains and Veľká Fatra National Park, surveys during 2011 to 2014 revealed that less than 30 individuals were present in these protected areas, with anthropic disturbances, poaching and insufficient counting methods used by forestry cited as the main causes of the unreliable population figures.[26]

- Estonia: There are 900 individuals in Estonia according to a 2001 estimate.[27] Although 180 lynx were legally hunted in Estonia in 2010, the country still has the highest known density of the species in Europe.[28]

- Latvia: According to a 2005 estimate, about 700 animals inhabit areas in Courland and Vidzeme.[29]

- Lithuania: The population is estimated at 80–100 animals.[30]

- Russia: As of 2013, the Russian lynx population is estimated as comprising 22,510 individuals and is considered abundant and stable in some regions.[1]

- Balkan peninsula: The Balkan lynx subspecies is found in Croatia, Montenegro, Albania, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Bulgaria and possibly Greece.[31] They can be found in remote mountainous regions of the Balkans, with the largest numbers in remote hills of western North Macedonia, eastern Albania and northern Albania. The Balkan Lynx is considered a national symbol of North Macedonia,[32] and it is depicted on the reverse of the Macedonian 5 denars coin, issued in 1993.[33] The name of Lynkestis, a Macedonian tribe, is translated as "Land of the Lynx". It has been on the brink of extinction for nearly 100 years. Numbers are estimated to be around 100, and the decline is due to illegal poaching.[34][35]

- Dinaric Alps and Julian Alps: Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina are home to approx. 130–200 lynx.[23][36] The Eurasian lynx had been considered extinct in these countries since the beginning of the 20th century. However, a successful reintroduction project was carried out in Slovenia in 1973, when three female and three male lynx from Slovakia were released in the Kočevski Rog forest.[37] Today, lynx are present in the Dinaric forests of the south and southeastern part of Slovenia and in the Croatian regions of Gorski kotar and Velebit, spanning the Dinaric Alps and over the Dinara Mountains into western Bosnia and Herzegovina. The lynx has been also spotted in the Julian Alps and elsewhere in western Slovenia, but the A1 motorway presents a significant hindrance to the development of the population there.[38] Croatia's Plitvice Lakes National Park is home to several pairs of the lynx. In the three countries, the Eurasian lynx is listed as an endangered species and protected by law. Realistic population estimates are 40 lynx in Slovenia, 40–60 in Croatia, and more than 50 in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Croatian massif Risnjak in Risnjak National Park probably got its name from the Croatian word for the lynx, ris.

- Hungary: The population is estimated at 10-12 animals, in the northern mountain ranges of the country close to Slovakia.

- Romania: over 2,000 Eurasian lynx live in Romania, including most of the Carpathian population. However, some experts consider these official population numbers to be overestimated.[39] Limited hunting is permitted but the population is stable.

- Bulgaria: the animal was declared extinct in Bulgaria in 1985, but sightings continued well into the 1990s. In 2006 an audio recording of a lynx mating call was made in the Strandzha mountain range in the southeast. Two years later an ear-marked individual was accidentally shot near Belogradchik in the northwest, and a few months later a mounted trap camera caught a glimpse of another individual. Further camera sightings followed in Osogovo as well as Strandzha, confirming that the animal has returned to the country. A thorough examination on the subject is yet to be made available.

- Ukraine: The Eurasian lynx is native to forested areas of the country. Before the 19th century it was common also in the forest steppe zone. Nowadays, the most significant populations remain in the Carpathian mountains and across the forests of Polesia. The population is estimated as 80–90 animals for the Polesia region and 350–400 for the forests of the Carpathians.[40]

Asia

Anatolia and Caucasus

In the Anatolian part of Turkey, the Eurasian lynx is present in the Lesser Caucasus, Kaçkar Mountains and Artvin Province.[41][42] In Ciglikara Nature Reserve located in the Taurus Mountains, 15 individuals were identified.[43] More than 50 individuals were identified and monitored at a forest-steppe mixed ecosystem in northwestern Anatolia by camera traps, genetic material and radiotelemetry between 2009 and 2019.[44][45] In Kars Province, a breeding population occurs in Sarıkamış-Allahuekber Mountains National Park.[46] Eurasian lynx and grey wolf can occur sympatrically, as they occupy different trophic niches.[47][48]

Central Asia

In Central Asia, it is native to Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan and the Chinese provinces of Xinjiang, Gansu, Qinghai, Sichuan, and Shaanxi, as well as to the northern slopes of Iran's Alborz Mountains, Mongolia.

In northern Pakistan, the Eurasian lynx was recorded at elevations of 1,067–5,000 m (3,501–16,404 ft) in Chitral District.[49][50] In India: Ladakh, Himachal Pradesh and most other Himalayan states.

In Nepal, a Eurasian lynx was sighted in the western Dhaulagiri massif in 1975.[51] It is also present above elevations of 3,800 m (12,500 ft) in Humla, Mustang and Dolpa Districts.[52]

Fossils of the Eurasian or a closely related Lynx species from the Late Pleistocene era and onward were excavated at various locations in the Japanese archipelago. Since no archaeological evidence after the Yayoi period was found, it was probably eradicated during the Jōmon period.[53]

Behaviour and ecology

Although they may hunt during the day when food is scarce, the Eurasian lynx is mainly nocturnal or crepuscular, and spends the day sleeping in dense thickets or other places of concealment. It lives solitarily as an adult. The hunting area of Eurasian lynx can be anything from 20 to 450 km2 (7.7 to 173.7 sq mi), depending on the local availability of prey. Males tend to hunt over much larger areas than females, which tend to occupy exclusive, rather than overlapping, hunting ranges. The Eurasian lynx can travel up to 20 km (12 mi) during one night, although about half this distance is more typical. They patrol regularly throughout all parts of their hunting range, using scent marks to indicate their presence to other individuals. As with other cats, its scent marks may consist of faeces, urine, or scrape marks,[54] with the former often being left in prominent locations along the boundary of the hunting territory. Eurasian lynx makes a range of vocalizations, but is generally silent outside of the breeding season. They have been observed to mew, hiss, growl, and purr, and, like domestic cats, will "chatter" at prey that is just out of reach. Mating calls are much louder, consisting of deep growls in the male, and loud "meow"-like sounds in the female. Eurasian lynx are secretive, and because the sounds they make are very quiet and seldom heard, their presence in an area may go unnoticed for years. Remnants of prey or tracks on snow are usually observed long before the animal is seen.[6]

Diet and hunting

Diet in Europe

Eurasian lynx in Europe, prey largely on small to fairly large sized mammals and birds. Among the recorded prey items for the species are hares, rabbits, marmots, squirrels, dormice, other rodents, mustelids (such as martens), grouse, red foxes, wild boar, chamois, young moose, roe deer, red deer, reindeer and other ungulates. Although taking on larger prey presents a risk to the animal, the bounty provided by killing them can outweigh the risks. The Eurasian lynx thus prefers fairly large ungulate prey, especially during winter when small prey is less abundant. Where common, roe deer appear to be the preferred prey species for the lynx.[55][56] Even where roe deer are quite uncommon, the deer are still quantitatively the favored prey species, though in summer smaller prey and occasional domestic sheep are eaten more regularly.[57] In parts of Finland, introduced white-tailed deer are eaten regularly. In some areas in Poland and Austria, red deer is the preferred prey, and in Switzerland, chamois is locally favored.[56] Eurasian lynx also feeds on carrion when available. Adult lynx require 1.1 to 2 kilograms (2.4 to 4.4 lb) of meat per day, and may take several days to fully consume some of their larger prey.[6]

Diet in Asia

In the Mediterranean mixed forest-steppe and subalpine ecosystems of Anatolia the main and most preferred prey of the Eurasian lynx is European hare, forming 79% to 99% of prey biomass eaten. Although the lynx is in sympatry with wild ungulates, such as wild goat, chamois, red deer and wild boar in these ecosystems, ungulate biomass in lynx diet does not exceed 10%.[47] In ten other study sites in the Black Sea region of northern Anatolia where roe deer can occur in high densities, lynx occurrence is positively correlated with European hare occurrence rather than roe deer.[58] Lynx in Anatolia also has physiological requirements and morphological adjustments similar to other lagomorph specialists, with a daily prey intake of about 900 g (32 oz).[47] It is therefore classified as lagomorph specialist. Diet studies in central [59][60] and northern Asia also indicate a diet mainly composed of lagomorphs and ungulate prey contributes in low amounts to lynx diet.[61]

Hunting

The main method of hunting is stalking, sneaking and jumping on prey, although they are also ambush predators when conditions are suitable. In winter certain snow conditions make this harder and the animal may be forced to switch to larger prey in Europe. Eurasian lynx hunt using both vision and hearing, and often climb onto high rocks or fallen trees to scan the surrounding area. A very powerful predator, these lynxes have successfully killed adult deer weighing to at least 150 kg (330 lb).[62]

Predators

In Russian forests, the most important predators of the Eurasian lynx are the grey wolf. Wolves kill and eat lynx that fail to escape into trees. Lynx populations decrease when wolves appear in a region and are likely to take smaller prey where wolves are active.

Wolverines are perhaps the most dogged of competitors for kills, often stealing lynx kills. Lynxes tend to actively avoid encounters with wolverines, but may sometimes fight them if defending kittens. Instances of predation on lynx by wolverines may occur, even perhaps on adults, but unlike wolf attacks on lynx are extremely rare if they do in fact occur. There are no known instances of lynx preying on a wolverine.

In two ecosystems of Anatolia, cannibalism was common and lynx found to form 5% to 8% of prey biomass in diet. Claws and bones analysed showed that sub-adult lynx were the victims of cannibalism during the mating and spring seasons.[47] Lynx were not found in the sympatrically occurring wolves' diet,[48] however, lynx itself was the predator of golden jackal, red fox, martens, domestic cat and dog.[47] Sometimes, Siberian tigers have also preyed on lynxes, as evidenced by examination of tiger stomach contents.[8][63] In Sweden, out of 33 deaths of lynx of a population being observed, one was probably killed by a wolverine.[64][65] Lynx compete for food with the predators described above, and also with the red fox, eagle owls, golden eagles, wild boar (which scavenge from lynx kills), and in the southern part of its range, the snow leopard and leopard as well.[8] Brown bears, although not (so far as is known) a predator of Eurasian lynx, are in some areas a semi-habitual usurpers of ungulate kills by lynxes, not infrequently before the cat has had a chance to consume its kill itself.[66][56]

Reproduction

The mating season of the Eurasian lynx lasts from January to April. The female typically comes into oestrus only once during this period, lasting from four to seven days. If the first litter is lost, a second period of oestrus is common. It does not appear to be able to control its reproductive behaviour based on prey availability. Gestation lasts from 67 to 74 days. Pregnant females construct dens in secluded locations, often protected by overhanging branches or tree roots. The den is lined with feathers, deer hair, and dry grass to provide bedding for the young. At birth, Eurasian lynx kittens weigh 240 to 430 g (8.5 to 15.2 oz) and open after ten to twelve days. They initially have plain, greyish-brown fur, attaining the full adult colouration around eleven weeks of age. They begin to take solid food at six to seven weeks, when they begin to leave the den, but are not fully weaned for five or six months. The den is abandoned two to three months after the kittens are born, but the young typically remain with their mother until they are around ten months of age. Eurasian lynx reach sexual maturity at two or three years, and have lived for twenty one years in captivity.[6] Females usually have two kittens, and litters with more than three kittens are rare.[67][68][69]

Conservation

The Eurasian lynx is included on CITES Appendix II and listed as a protected species in the Berne Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats, Appendix III. Hunting lynx is illegal in many range countries, with the exception of Estonia, Latvia, Russia, Armenia and Iraq.[1] Since 2005, the Norwegian government sets national population goals, while a committee of representatives from county assemblies decide on hunting quotas.[11]

See also

- Bobcat

- Iberian lynx

- Canada lynx

- List of largest cats

References

- Breitenmoser, U.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Lanz, T.; von Arx, M.; Antonevich, A.; Bao, W. & Avgan, B. (2015). "Lynx lynx". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T12519A121707666.

- Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Species Lynx lynx". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 541. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Felis lynx". Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Tomus I (decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. p. 43.

- von Arx, M.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Zimmermann, F.; Breitenmoser, U., eds. (June 2004). Status and conservation of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) in Europe in 2001 (PDF). Eurasian Lynx Online Information System ELOIS.

- Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z.; Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 11): 42−45.

- Sunquist, M.; Sunquist, F. (2002). "Eurasian Lynx Lynx lynx (Linnaeus, 1758)". Wild cats of the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 164–176. ISBN 978-0-226-77999-7.

- Nowell, K.; Jackson, P. (1996). "Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx (Linnaeus, 1758)". Wild cats: Status survey and Conservation Action Plan. Gland: IUCN Cat Specialist Group. pp. 101–106.

- Heptner, V. G.; Sludskij, A. A. (1992) [1972]. "Lynx". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 2. Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats)]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 524–636.

- Breitenmoser, U.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Okarma, H.; Kaphegyi, T. (2000). Action plan for the conservation of the Eurasian lynx in Europe (Lynx lynx) (PDF). Nature and Environment. 112. Council of Europe.

- Rueness, E. K.; Jorde, P. E.; Hellborg, L.; Stenseth, N. C.; Ellegren, H.; Jakobsen, K. S. (2003). "Cryptic population structure in a large, mobile mammalian predator: the Scandinavian lynx" (PDF). Molecular Ecology. 12 (10): 2623–2633. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01952.x.

- Linnell, J. D.; Broseth, H.; Odden, J.; Nilsen, E. B. (2010). "Sustainably harvesting a large carnivore? Development of Eurasian lynx populations in Norway during 160 years of shifting policy". Environmental Management. 45 (5): 1142–1154. doi:10.1007/s00267-010-9455-9.

- "Swedish Environmental Protection Agency & Council For Predator Issues".

- "RKTL – Ilves". Rktl.fi. 2010-10-14. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- "Metsästäjäliitto on tyytyväinen ilveksen pyyntilupien lisäämiseen | Suomen Metsästäjäliitto – Finlands Jägarförbund r.y". Metsastajaliitto.fi. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- Stahl, P.; Vandel, J.-M. (1998). "Distribution of the lynx in the French Alps" (PDF). Hystrix. 10 (1): 3–15. doi:10.4404/hystrix-10.1-4117.

- Molinari, P.; Rotelli, L.; Catello, M.; & Bassano, B. (2001). "Present status and distribution of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) in the Italian Alps" (PDF). Hystrix. 12 (2): 3−9.

- Molinari-Jobin, A.; Marboutin, E.; Wölfl, S.; Wölfl, M.; Molinari, P.; Fasel, M.; Kos, I.; Blažič, M.; Breitenmoser, C.; Fuxjäger, C.; Huber, T.; Koren, I.; Breitenmoser, U. (2010). "Recovery of the Alpine lynx Lynx lynx metapopulation" (PDF). Oryx. 44 (2): 267–275. doi:10.1017/S0030605309991013.

- Trouwborst, A. (2010). "Managing the carnivore comeback: international and EU species protection law and the return of lynx, wolf and bear to Western Europe". Journal of Environmental Law. 22 (3): 347–372. doi:10.1093/jel/eqq013.

- Robinson, Jennifer (March 25, 2019). "NATURE: Forest Of The Lynx". KPBS. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- "Journal of Wildlife Diseases 38" (PDF). Wildlife Disease Association. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-12-15. Retrieved 2009-06-12. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hetherington, D.; Gorman, M. (2007). "Using prey densities to estimate the potential size of reintroduced populations of Eurasian lynx" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 137 (1): 37–44. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2007.01.009.

- Hetherington, D. A.; Miller, D. R.; Macleod, C. D.; Gorman, M. L. (2008). "A potential habitat network for the Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx in Scotland" (PDF). Mammal Review. 38 (4): 285–303. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2008.00117.x.

- "Large Carnivore Initiative for Europe Species fact sheet – Lynx lynx". Large Carnivore Initiative for Europe. Retrieved May 28, 2007.

- "Concise Statistical Yearbook of Poland" (PDF). 2011. Retrieved 2019-02-10.

- Krištofík, J.; Danko, Š.; Hell, J.; Bučko, J.; Hanzelová, V.; Špakulová, M. (2012). "Rys ostrovid - Lynx lynx". Cicavce Slovenska, rozšírenie, bionómia a ochrana [Mammals of Slovakia, Distribution, Bionomy and Protection]. Veda, Bratislava. ISBN 978-80-224-1264-3.

- Kubala, J.; Smolko, P.; Zimmermann, F.; Rigg, R.; Tám, B.; Iľko, T.; Foresti, D.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Kropil, R.; Breitenmoser, U. (2017). "Robust monitoring of the Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx in the Slovak Carpathians reveals lower numbers than officially reported" (PDF). Oryx. 53 (3): 548–556. doi:10.1017/S003060531700076X.

- Valdmann, Harri. "Estonia – 3. Size & trend". Eurasian Lynx Online Information System for Europe. Archived from the original on November 22, 2004. Retrieved 2007-05-28.

- Eestist asustatakse Poola metsadesse ümber kuni 40 ilvest. Eesti Päevaleht, 1-3-2011. (in Estonian)

- "Latvia". Eurasian Lynx Online Information System for Europe. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- "Lūšis – vienintelė kačių šeimos rūšis Lietuvoje". Ministry of Environment of the Republic of Lithuania. Retrieved 2011-04-29.

- "ELOIS – Populations – Balkan population". Kora.ch. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- "Macedonia Wildcats Fight for Survival", by Konstantin Testorides, Associated Press; in The Washington Post, 4 November 2006. – Retrieved on 30 March 2009.

- Macedonian currency: Coins in circulation. National Bank of the Republic of Macedonia.

- "Poachers put Balkan lynx on brink of extinction". Terradaily. AFP. 22 February 2009. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "Action urged to save Balkan lynx". BBC. 3 November 2006. Retrieved May 28, 2007.

- "World of Animals at Plitvice Lakes". Plitvice Lakes National Park World of Animals. Archived from the original on March 5, 2009.

- "Ris v Sloveniji" [The Lynx in Slovenia] (PDF). Strategija ohranjanja in trajnostnega upravljanja navadnega risa (Lynx lynx) v Sloveniji 2016–2026 [The Strategy for Preserving and Sustainably Managing the Common Lynx (Lynx lynx) in Slovenia 2016–2026]. Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning, Government of the Republic of Slovenia. 2016. p. 7.

- "Risom v Sloveniji in na Hrvaškem se obeta svetlejša prihodnost" [Brighter Future Expected for the Lynx of Slovenia and Croatia]. Delo.si (in Slovenian). 14 April 2017.

- "Status and conservation of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) in Europe in 2001" (PDF). Coordinated research projects for the conservation and management of carnivores in Switzerland KORA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-19. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- Shkvyria, M. G.; Shevchenko, L.S. (2009). "Lynx". In Akimova, I.A.; Globalconsulting (eds.). Red book of Ukraine. Kyiv: Wildlife Disease Association. p. 546. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- Ambarli, H.; Mengüllüoglu, D.; Bilgin, C. (2010). "First camera trap pictures of Eurasian lynx from Turkey". Cat News (52): 32.

- Albayrak, I. (2012). "New record of Lynx lynx (L., 1758) in Turkey (Mammalia: Carnivora)" (PDF). Turkish Journal of Zoology. 36 (6): 814–819.

- Avgan, B.; Zimmermann, F.; Güntert, M.; Arıkan, F.; Breitenmoser, U. (2014). "The first density estimation of an isolated Eurasian lynx population in Southwest Asia". Wildlife Biology. 20 (4): 217–221. doi:10.2981/wlb.00025.

- Mengüllüoğlu, D. (2010). An inventory of medium and large mammal fauna in Pine forests of Beypzari through camera trapping (MSc thesis). Ankara: Middle East Technical University. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.18368.84486.

- Mengüllüoğlu, D.; Fickel, J.; Hofer, H.; Förster, D. W. (2019). "Non-invasive faecal sampling reveals spatial organization and improves measures of genetic diversity for the conservation assessment of territorial species: Caucasian lynx as a case species". PLOS ONE. 14 (5): e0216549. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0216549. PMC 6510455. PMID 31075125.

- Chynoweth, M.; Coban, E.; Şekercioğlu, Ç. (2015). "Conservation of a new breeding population of Caucasian lynx (Lynx lynx dinniki) in eastern Turkey". Turkish Journal of Zoology. 39 (3): 541–543. doi:10.3906/zoo-1405-10.

- Mengüllüoğlu, D.; Ambarlı, H.; Berger, A.; Hofer, H. (2018). "Foraging ecology of Eurasian lynx populations in southwest Asia: Conservation implications for a diet specialist". Ecology and Evolution. 8 (18): 9451–9463. doi:10.1002/ece3.4439. PMC 6194280. PMID 30377514.

- Mengüllüoğlu, D.; İlaslan, E.; Emir, H.; Berger, A. (2019). "Diet and wild ungulate preferences of wolves in northwestern Anatolia during winter". PeerJ. 7: e7446. doi:10.7717/peerj.7446. PMC 6708370. PMID 31497386.

- Din, J. U.; Nawaz, M. A. (2010). "Status of the Himalayan Lynx in District Chitral, NWFP, Pakistan". The Journal of Animal and Plant Sciences. 20 (1): 17–22.

- Din, J. U.; Zimmermann, F.; Ali, M.; Shah, K. A.; Ayub, M.; Nawaz, M. A. (2013). "Population assessment of Himalayan lynx (Lynx lynx isabellinus) and conflict with humans in the Hindu Kush mountain range of District Chitral, Pakistan". Journal of Biodiversity and Environmental Sciences. 6 (2): 32–39.

- Fox, J. L. (1985). "An observation of lynx in Nepal". Journal of Bombay Natural History Museum. 82: 394–395.

- Kusi, N.; Manandhar, P.; Subba, S. A.; Thapa, K.; Thapa, K.; Shrestha, B.; Pradhan, N. M. B.; Dhakal, M.; Aryal, N.; Werhahn, G. (2018). "Shadowed by the ghost: the Eurasian lynx in Nepal". Cat News (68): 16–19.

- Hasegawa, Y.; Kaneko, H.; Tachibana, M.; Tanaka, G. (2011). "日本における後期更新世~前期完新世産のオオヤマネコLynxについて" [A study of the extinct Japanese Lynx from the Late Pleistocene to the Early Holocene] (PDF). Bulletin of Gunma Museum of Natural History (in Japanese). 15: 43−80.

- Mengüllüoğlu, D.; Berger, A.; Förster, D. W.; Hofer, H. (2015). "Faecal marking behaviour in Eurasian lynx, Lynx lynx". doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.4339.8163. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Molinari-Jobin, A.; Zimmermann, F.; Ryser, A.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Capt, S.; Breitenmoser, U.; Molinari, P.; Haller, H.; Eyholzer, R. (2007). "Variation in diet, prey selectivity and home-range size of Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx in Switzerland" (PDF). Wildlife Biology. 13 (4): 393. doi:10.2981/0909-6396(2007)13[393:VIDPSA]2.0.CO;2.

- Krofel, M.; Huber, D.; Kos, I. (2011). "Diet of Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx in the northern Dinaric Mountains (Slovenia and Croatia)". Acta Theriologica. 56 (4): 315–322. doi:10.1007/s13364-011-0032-2.

- Odden, J.; Linnell, J. D. C.; Andersen, R. (2006). "Diet of Eurasian lynx, Lynx lynx, in the boreal forest of southeastern Norway: The relative importance of livestock and hares at low roe deer density". European Journal of Wildlife Research. 52 (4): 237. doi:10.1007/s10344-006-0052-4.

- Soyumert, A.; Ertürk, A.; Tavşanoğlu, Ç. (2019). "The importance of lagomorphs for the Eurasian lynx in Western Asia: Results from a large scale camera-trapping survey in Turkey". Mammalian Biology. 95: 18–25. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2019.01.003.

- Weidong, B. (2010). "Eurasian lynx in China - present status and conservation challenges" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 5): 22–26.

- Werhahn, G.; Kusi, N.; Karmacharya, D.; Man Sherchan, A.; Manandhar, P.; Manandhar, S.; Bhatta, T. R.; Joshi, J.; Bhattarai, S.; Sharma, A.N.; Kaden, J. (2018). "Eurasian lynx and Pallas's cat in Dolpa district of Nepal: genetics, distribution and diet". Cat News (67): 34–36.

- Sedalischev, V. T.; Odnokurtsev, V. A.; Ohlopkov, I. M. (2014). "Материалы по экологии рыси (Lynx lynx L., 1758) Якутии" [Materials on ecology of the lynx (Lynx lynx, 1758) in Yakutia]. News of Samara Scientific Center Russian Academy of Sciences (in Russian) (16): 175–182.

- Hunter, L. (2011). Carnivores of the World. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15228-8.

- Boitani, L. (2003). Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. University of Chicago Press. pp. 265–. ISBN 978-0-226-51696-7.

- Andrén, Henrik; Linnell, J. D. C.; Liberg, O.; Andersen, R.; Danell, A.; Karlsson, J.; Odden, J.; Moa, P. F.; Ahlqvist, P.; Kvam, T.; Franzén, R.; Segerström, P. (2006). "Survival rates and causes of mortality in Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) in multi-use landscapes". Biological Conservation. 131 (1): 23–32. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2006.01.025.

- Andren, H.; Persson, J.; Mattisson, J.; Danell, A. C. (2011). "Modelling the combined effect of an obligate predator and a facultative predator on a common prey: lynx Lynx lynx and wolverine Gulo gulo predation on reindeer Rangifer tarandus". Wildlife Biology. 17 (1): 33–43. doi:10.2981/10-065.

- Krofel, M.; Kos, I.; Jerina, K. (2012). "The noble cats and the big bad scavengers: Effects of dominant scavengers on solitary predators". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 66 (9): 1297. doi:10.1007/s00265-012-1384-6.

- Henriksen, H. B.; Andersen, R.; Hewison, A. J. M.; Gaillard, J. M.; Bronndal, M.; Jonsson, S.; Linnell, J. D.; Odden, J. (2005). "Reproductive biology of captive female Eurasian lynx, Lynx lynx". European Journal of Wildlife Research. 51 (3): 151–156. doi:10.1007/s10344-005-0104-1.

- Breitenmoser‐Würsten, C.; Vandel, J. M.; Zimmermann, F.; Breitenmoser, U. (2007). "Demography of lynx Lynx lynx in the Jura Mountains" (PDF). Wildlife Biology. 13 (4): 381–392. doi:10.2981/0909-6396(2007)13[381:DOLLLI]2.0.CO;2.

- Gaillard, J. M.; Nilsen, E. B.; Odden, J.; Andrén, H.; Linnell, J. D. (2014). "One size fits all: Eurasian lynx females share a common optimal litter size". Journal of Animal Ecology. 83 (1): 107–115. doi:10.1111/1365-2656.12110. PMID 23859302.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lynx lynx. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Lynx lynx |

- IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group: Eurasian lynx

- Eurasian Lynx Online Information System for Europe

- Eurasian Lynx from the Wild Cats: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan

- Large Carnivore Initiative for Europe

- Balkan Lynx Conservation Compendium

- DinaRis – lynx research project in Slovenia and Croatia

- Lynx archaeological research project in Craven, North Yorkshire

- Deksne, G.; Laakkonen, J.; Näreaho, A.; Jokelainen, P.; Holmala, K.; Kojola, I.; Sukura, A. (2013). "Endoparasites of the Eurasian Lynx (Lynx lynx) in Finland". Journal of Parasitology. 99 (2): 229–234. doi:10.1645/GE-3161.1. PMID 23016871.

- Free-ranging Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) as host of Toxoplasma gondii in Finland

- Molecular identification of Taenia spp. in the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) from Finland (a putative new species of Taenia found in Eurasian lynx)

- First Hard Evidence of Lynx (Lynx Lynx L.) Presence in Bulgaria − published in Biotechnology and Biotechnological Equipment

- Lynx UK Trust – Organisation driving efforts to reintroduce Eurasian lynx across the UK