European badger

The European badger (Meles meles) also known as the Eurasian badger, is a badger species in the family Mustelidae native to almost all of Europe and some parts of Western Asia. It is classified as least concern on the IUCN Red List as it has a wide range and a large stable population size, and is thought to be increasing in some regions. Several subspecies are recognized with the nominate subspecies (M. meles meles) predominating in most of Europe.[1]

| European badger | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Mustelidae |

| Genus: | Meles |

| Species: | M. meles |

| Binomial name | |

| Meles meles | |

| |

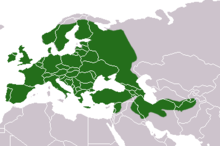

| European badger range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Ursus meles Linnaeus, 1758 | |

The European badger is a powerfully built black, white, brown and grey animal with a small head, a stocky body, small black eyes and short tail. Its weight varies, being 7–13 kg (15–29 lb) in spring but building up to 15–17 kg (33–37 lb) in autumn before the winter sleep period. It is nocturnal and is a social, burrowing animal that sleeps during the day in one of several setts in its territorial range. These burrows have multiple chambers and entrances, and are extensive systems of underground passages of 35–81 m (115–266 ft) length. They house several badger families that use these setts for decades. Badgers are very fussy over the cleanliness of their burrow, carrying in fresh bedding and removing soiled material, and they defecate in latrines strategically situated outside their setts.

Although classified as a carnivore, the European badger feeds on a wide variety of plant and animal foods, feeding on earthworms, large insects, small mammals, carrion, cereals and tubers. Litters of up to five cubs are produced in spring. The young are weaned a few months later but usually remain within the family group. The European badger has been known to share its burrow with other species such as rabbits, red foxes and raccoon dogs, but it can be ferocious when provoked, a trait which has been exploited in the now illegal blood sport of badger-baiting. Badgers are a reservoir for bovine tuberculosis, which also affects cattle. In England, culling of badger populations is used to reduce the incidence of bovine tuberculosis in cattle.[2]

Nomenclature

The source of the word "badger" is uncertain. The Oxford English Dictionary states it probably derives from "badge" + -ard, referring to the white mark borne like a badge on its forehead, and may date to the early sixteenth century.[3] The French word bêcheur (digger) has also been suggested as a source.[4] A male badger is a boar, a female is a sow, and a young badger is a cub. A badger's home is called a sett.[5] Badger colonies are often called clans.

The far older name "brock" (Old English: brocc), (Scots: brock) is a Celtic loanword (cf. Gaelic broc and Welsh broch, from Proto-Celtic *brokko) meaning "grey".[3] The Proto-Germanic term was *þahsu- (cf. German Dachs, Dutch das, Norwegian svin-toks; Early Modern English: dasse), probably from the PIE root *tek'- "to construct," so the badger would have been named after its digging of setts (tunnels); the Germanic term *þahsu- became taxus or taxō, -ōnis in Latin glosses, replacing mēlēs ("marten" or "badger"),[6] and from these words the common Romance terms for the animal evolved (Italian tasso, French tesson/taisson/tasson—now blaireau is more common—, Catalan toixó, Spanish tejón, Portuguese texugo) except Asturian melandru.[7]

Until the mid-18th century, European badgers were variously known in English as 'brock', 'pate', 'grey' and 'bawson'. The name "bawson" is derived from "bawsened", which refers to something striped with white. "Pate" is a local name which was once popular in northern England. The name "badget" was once common, but restricted to Norfolk, while "earth dog" was used in southern Ireland.[8] The badger is commonly referred to in Welsh as a "mochyn daear" (earth pig). [9]

Taxonomy

Ursus meles was the scientific name used by Carl Linnaeus in 1758, who described the badger in his work Systema Naturae.[10]

Evolution

The species likely evolved from the Chinese Meles thorali of the early Pleistocene. The modern species originated during the early Middle Pleistocene, with fossil sites occurring in Episcopia, Grombasek, Süssenborn, Hundsheim, Erpfingen, Koneprusy, Mosbach 2, and Stránská Skála. A comparison between fossil and living specimens shows a marked progressive adaptation to omnivory, namely in the increase in the molars' surface areas and the modification of the carnassials. Occasionally, badger bones are discovered in earlier strata, due to the burrowing habits of the species.[11][12]

Subspecies

In the 19th and 20th centuries, several badger type specimens were described and proposed as subspecies. As of 2005, eight subspecies are recognized as valid taxa.[13]

| Subspecies | Trinomial authority and synonyms | Description | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common badger (M. m. meles)

|

Linnaeus, 1758 taxus (Boddaert, 1785) |

A large subspecies with a strongly developed sagittal crest, it has a soft pelage and relatively dense underfur. The back has a relatively pure silvery-grey tone, while the main tone of the head is pure white. The dark stripes are wide and black, while the white fields fully extend along the upper and lateral parts of the neck. It can weigh up to 20–24 kg in autumn, with some specimens attaining even larger sizes.[14] | Continental Europe, except for the Iberian Peninsula. Its eastern range encompasses the European area of the former Soviet Union eastward to the Volga, Crimea, Ciscaucasia, and the northern Caucasus |

| Transcaucasian badger (M. m. canescens)

|

Blanford, 1875[15] minor (Satunin, 1905) |

A small subspecies with a dirty-greyish back and brown highlights; its head is identical to the common badger, though with weaker crests; its upper molars are elongated in a similar way as the Asian badger's.[16] | Transcaucasia, the Kopet Dag, Turkmenistan, Iran, Afghanistan and possibly Asia Minor |

| Iberian badger (M. m. marianensis) | Graells, 1897[17] mediterraneus (Barrett-Hamilton, 1899) |

Spain and Portugal | |

| Cretan badger (M. m. arcalus)

|

Miller, 1907[18] | Crete | |

| Rhodes badger (M. m. rhodius) | Festa, 1914[19] | Rhodes | |

| Kizlyar badger (M. m. heptneri) | Ognev, 1931 | A large subspecies, it exhibits several traits of the Asian badger, namely its very pale, dull, dirty-greyish-ocherous colour and narrow head stripes.[16] | Steppe region of northeastern Ciscaucasia, the Kalmytsk steppes and the Volga delta |

| Fergana badger (M. m. severzovi) | Heptner, 1940[20] bokharensis (Petrov,1953) |

A small subspecies with a relatively pure, silvery-grey back with no yellow sheen. The head stripes are wide and occupy the whole ear. Its skull exhibits several features which are transitory between the Asian and European badger.[16] | Right tributaries of the Panj and upper Amu Darya rivers, the Pamir-Alay system, the Fergana Valley and adjoining mountains[20] |

| Norwegian badger (M. m. milleri)

|

Baryshnikov, Puzachenko and Abramov, 2003[21] | This subspecies has a smaller skull and smaller teeth than the nominate badger subspecies in Sweden and Finland.[21] | Southwestern Norway, west of Telemark[21] |

Description

European badgers are powerfully built animals with small heads, thick, short necks, stocky, wedge-shaped bodies and short tails. Their feet are plantigrade[22] or semidigitigrade[23] and short, with five toes on each foot.[24] The limbs are short and massive, with naked lower surfaces on the feet. The claws are strong, elongated and have an obtuse end, which assists in digging.[25] The claws are not retractable, and the hind claws wear with age. Old badgers sometimes have their hind claws almost completely worn away from constant use.[26] Their snouts, which are used for digging and probing, are muscular and flexible. The eyes are small and the ears short and tipped with white. Whiskers are present on the snout and above the eyes.

Boars typically have broader heads, thicker necks and narrower tails than sows, which are sleeker, have narrower, less domed heads and fluffier tails. The guts of badgers are longer than those of red foxes, reflecting their omnivorous diet. The small intestine has a mean length of 5.36 metres (17.6 ft) and lacks a cecum. Both sexes have three pairs of nipples but these are more developed in females.[24] European badgers cannot flex their backs as martens, polecats and wolverines can, nor can they stand fully erect like honey badgers, though they can move quickly at full gallop.[25]

Adults measure 25–30 cm (9.8–11.8 in) in shoulder height,[27] 60–90 cm (24–35 in) in body length, 12–24 cm (4.7–9.4 in) in tail length, 7.5–13 cm (3.0–5.1 in) in hind foot length and 3.5–7 cm (1.4–2.8 in) in ear height. Males (or boars) slightly exceed females (or sows) in measurements, but can weigh considerably more. Their weights vary seasonally, growing from spring to autumn and reaching a peak just before the winter. During the summer, European badgers commonly weigh 7–13 kg (15–29 lb) and 15–17 kg (33–37 lb) in autumn.[28]

The average weight of adults in Białowieża Forest, Poland were 10.2 kg (22 lb) in spring but weighed up to 19 kg (42 lb) in autumn, 46% higher than their spring low mass.[29] In Woodchester Park, England, adults in spring weighed on average 7.9 kg (17 lb) and in fall average 9.5 kg (21 lb).[30] In Doñana National Park, average weight of adult badgers is reported as 6 to 7.95 kg (13.2 to 17.5 lb), perhaps in accordance with Bergmann's rule, that its size decreases in relatively warmer climates closer to the equator.[31][32] Sows can attain a top autumn weight of around 17.2 kg (38 lb), while exceptionally large boars have been reported in autumn. The heaviest verified was 27.2 kg (60 lb), though unverified specimens have been reported to 30.8 kg (68 lb) and even 34 kg (75 lb) (if so, the heaviest weight for any terrestrial mustelid). If average weights are used, the European badger ranks as the second largest terrestrial mustelid, behind only the wolverine.[28][33] Although their sense of smell is acute, their eyesight is monochromatic as has been shown by their lack of reaction to red lanterns. Only moving objects attract their attention. Their hearing is no better than that of humans.[34]

_fur_skin.jpg)

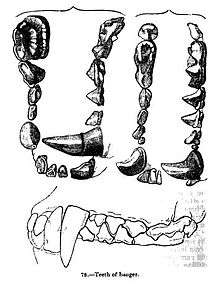

European badger skulls are quite massive, heavy and elongated. Their braincases are oval in outline, while the facial part of their skulls is elongated and narrow.[36] Adults have prominent sagittal crests which can reach 15 mm tall in old males,[37] and are more strongly developed than those of honey badgers.[38] Aside from anchoring the jaw muscles, the thickness of the crests protect their skulls from hard blows.[39] Similar to martens,[40] the dentition of European badgers is well-suited for their omnivorous diets. Their incisors are small and chisel-shaped, their canine teeth are prominent and their carnassials are not overly specialized. Their molars are flattened and adapted for grinding.[37] Their jaws are powerful enough to crush most bones; a provoked badger was once reported as biting down on a man's wrist so severely that his hand had to be amputated.[41] The dental formula is 3.1.3.13.1.4.2.

Scent glands are present below the base of the tail and on the anus. The subcaudal gland secretes a musky-smelling, cream-coloured fatty substance, while the anal glands secrete a stronger-smelling, yellowish-brown fluid.[37]

Fur

In winter, the fur on the back and flanks is long and coarse, consisting of bristly guard hairs with a sparse, soft undercoat. The belly fur consists of short, sparse hairs, with skin being visible in the inguinal region. Guard hair length on the middle of the back is 75–80 mm (3.0–3.1 in) in winter. Prior to the winter, the throat, lower neck, chest and legs are black. The belly is of a lighter, brownish tint, while the inguinal region is brownish-grey. The general colour of the back and sides is light silvery-grey, with straw-coloured highlights on the sides. The tail has long and coarse hairs, and is generally the same colour as the back. Two black bands pass along the head, starting from the upper lip and passing upwards to the whole base of the ears. The bands sometimes extend along the neck and merge with the colour of the upper body. The front parts of the bands are 15 mm (0.6 in), and widen to 45–55 mm (1.8–2.2 in) in the ear region. A wide, white band extends from the nose tip through the forehead and crown. White markings occur on the lower part of the head, and extend backwards to a great part of the neck's length. The summer fur is much coarser, shorter and sparser, and is deeper in colour, with the black tones becoming brownish, sometimes with yellowish tinges.[25] Partial melanism in badgers is known, and albinos are not uncommon. Albino badgers can be pure white or yellowish with pink eyes. Erythristic badgers are more common than the former, being characterized by having a sandy-red colour on the usually black parts of the body. Yellow badgers are also known.[42]

Behaviour

Social and territorial behaviour

European badgers are the most social of badgers,[43] forming groups of six adults on average, though larger associations of up to 23 individuals have been recorded. Group size may be related to habitat composition. Under optimal conditions, badger territories can be as small as 30 ha, but may be as large as 150 ha in marginal areas.[44] Badger territories can be identified by the presence of communal latrines and well-worn paths.[45] It is mainly males that are involved in territorial aggression. A hierarchical social system is thought to exist among badgers and large powerful boars seem to assert dominance over smaller males. Large boars sometimes intrude into neighboring territories during the main mating season in early spring.

Sparring and more vicious fights generally result from territorial defense in the breeding season.[46] However, in general, animals within and outside a group show considerable tolerance of each other. Boars tend to mark their territories more actively than sows, with their territorial activity increasing during the mating season in early spring.[44] Badgers groom each other very thoroughly with their claws and teeth. Grooming may have a social function.[47] They are crepuscular and nocturnal in habits.[47] Aggression among badgers is largely associated with territorial defence and mating. When fighting, they bite each other on the neck and rump, while running and chasing each other and injuries incurred in such fights can be severe and sometimes fatal. When attacked by dogs or sexually excited, badgers may raise their tails and fluff up their fur.[48]

European badgers have an extensive vocal repertoire. When threatened they emit deep growls and when fighting make low kekkering noises. They bark when surprised, whicker when playing or in distress,[48] and emit a piercing scream when alarmed or frightened.[49]

Reproduction and development

Estrus in European badgers lasts four to six days and may occur throughout the year, though there is a peak in spring. Sexual maturity in boars is usually attained at the age of twelve to fifteen months but this can range from nine months to two years. Males are normally fecund during January–May, with spermatogenesis declining in summer. Sows usually begin ovulating in their second year, though some exceptionally begin at nine months. They can mate at any time of the year, though the main peak occurs in February–May, when mature sows are in postpartal estrus and young animals experience their first estrus. Matings occurring outside this period typically occur in sows which either failed to mate earlier in the year or matured slowly.[50] Badgers are usually monogamous; boars typically mate with one female for life, whereas sows have been known to mate with more than one male.[51] Mating lasts for fifteen to sixty minutes, though the pair may briefly copulate for a minute or two when the sow is not in estrus. A delay of two to nine months precedes the fertilized eggs implanting into the wall of the uterus, though matings in December can result in immediate implantation. Ordinarily, implantation happens in December, with a gestation period lasting seven weeks. Cubs are usually born in mid-January to mid-March within underground chambers containing bedding. In areas where the countryside is waterlogged, cubs may be born above ground in buildings. Typically, only dominant sows can breed, as they suppress the reproduction of subordinate females.[50]

The average litter consists of one to five cubs.[50] Although many cubs are sired by resident males, up to 54% can be fathered by boars from different colonies.[44] Dominant sows may kill the cubs of subordinates.[48] Cubs are born pink, with greyish, silvery fur and fused eyelids. Neonatal badgers are 12 cm (5 in) in body length on average and weigh 75 to 132 grams (2.6 to 4.7 oz), with cubs from large litters being smaller.[50] By three to five days, their claws become pigmented, and individual dark hairs begin to appear.[51] Their eyes open at four to five weeks and their milk teeth erupt about the same time. They emerge from their setts at eight weeks of age, and begin to be weaned at twelve weeks, though they may still suckle until they are four to five months old. Subordinate females assist the mother in guarding, feeding and grooming the cubs.[50] Cubs fully develop their adult coats at six to nine weeks.[51] In areas with medium to high badger populations, dispersal from the natal group is uncommon, though badgers may temporarily visit other colonies.[47] Badgers can live for up to about fifteen years in the wild.[49]

Denning behaviour

Like other badger species, European badgers are burrowing animals. However, the dens they construct (called setts) are the most complex, and are passed on from generation to generation.[52] The number of exits in one sett can vary from a few to fifty. These setts can be vast, and can sometimes accommodate multiple families. When this happens, each family occupies its own passages and nesting chambers. Some setts may have exits which are only used in times of danger or play. A typical passage has a 22–63 cm (8.7–24.8 in) wide base and a 14–32 cm (5.5–12.6 in) height. Three sleeping chambers occur in a family unit, some of which are open at both ends. The nesting chamber is located 5–10 m (5.5–10.9 yd) from the opening, and is situated more than a 1 m (1.1 yd) underground, in some cases 2.3 m (2.5 yd). Generally, the passages are 35–81 m (38–89 yd) long. The nesting chamber is on average 74 cm × 76 cm (29 in × 30 in), and are 38 cm (15 in) high.[53]

Badgers dig and collect bedding throughout the year, particularly in autumn and spring. Sett maintenance is usually carried out by subordinate sows and dominant boars. The chambers are frequently lined with bedding, brought in on dry nights, which consists of grass, bracken, straw, leaves and moss. Up to 30 bundles can be carried to the sett on a single night. European badgers are fastidiously clean animals which regularly clear out and discard old bedding. During the winter, they may take their bedding outside on sunny mornings and retrieve it later in the day.[44] Spring cleaning is connected with the birth of cubs, and may occur several times during the summer to prevent parasite levels building up.[53]

If a badger dies within the sett, its conspecifics will seal off the chamber and dig a new one. Some badgers will drag their dead out of the sett and bury them outside.[54] A sett is almost invariably located near a tree, which is used by badgers for stretching or claw scraping.[55] Badgers defecate in latrines, which are located near the sett and at strategic locations on territorial boundaries or near places with abundant food supplies.[47]

In extreme cases, when there is a lack of suitable burrowing grounds, badgers may move into haystacks in winter.[53] They may share their setts with red foxes or European rabbits. The badgers may provide protection for the rabbits against other predators. The rabbits usually avoid predation by the badgers by inhabiting smaller, hard to reach chambers.[56]

Winter sleep

Badgers begin to prepare for winter sleep during late summer by accumulating fat reserves, which reach a peak in October. During this period, the sett is cleaned and the nesting chamber is filled with bedding. Upon retiring to sleep, badgers block their sett entrances with dry leaves and earth. They typically stop leaving their setts once snow has fallen. In Russia, badgers retire for their winter sleep from late October to mid-November and emerge from their setts in March and early April.[57] In areas such as England and Transcaucasia, where winters are less harsh, badgers either forgo winter sleep entirely or spend long periods underground, emerging in mild spells.[49]

Ecology

Distribution and habitat

The European badger is native to most of Europe and parts of western Asia. In Europe its range includes Albania, Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Crete, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and Ukraine. In Asia it occurs in Afghanistan, China (Xinjiang), Iran, Iraq and Israel.[1]

The distributional boundary between the ranges of European and Asian badgers is the Volga River, the European species being situated on the western bank. They are common in European Russia, with 30,000 individuals having been recorded there in 1990. They are abundant and increasing throughout their range, partly due to a reduction in rabies in Central Europe. In the UK, badgers experienced a 77% increase in numbers during the 1980s and 1990s.[1] The badger population in Great Britain in 2012 is estimated to be 300,000.[58]

The European badger is found in deciduous and mixed woodlands, clearings, spinneys, pastureland and scrub, including Mediterranean maquis shrubland. It has adapted to life in suburban areas and urban parks, although not to the extent of red foxes. In mountainous areas it occurs up to an altitude of 2,000 metres (6,600 ft).[1][49]

Badger tracking to study their behavior and territories has been done in Ireland using Global Positioning Systems.[59]

Diet

European badgers are among the least carnivorous members of the Carnivora;[60] they are highly adaptable and opportunistic omnivores, whose diet encompasses a wide range of animals and plants. Earthworms are their most important food source, followed by large insects, carrion, cereals, fruit and small mammals including rabbits, mice, shrews, moles and hedgehogs. Insect prey includes chafers, dung and ground beetles, caterpillars, leatherjackets, and the nests of wasps and bumblebees. They are able to destroy wasp nests, consuming the occupants, combs, and envelope, such as that of Vespula rufa nests, since thick skin and body hair protect the badgers from stings.[61] Cereal food includes wheat, oats, maize and occasionally barley. Fruits include windfall apples, pears, plums, blackberries, bilberries, raspberries, strawberries, acorns, beechmast, pignuts and wild arum corms.

Occasionally, they feed on medium to large birds, amphibians, small reptiles, including tortoises, snails, slugs, fungi, and green food such as clover and grass, particularly in winter and during droughts.[62] Badgers characteristically capture large numbers of one food type in each hunt. Generally, they do not eat more than 0.5 kg (1.1 lb) of food per day, with young specimens yet to attain one year of age eating more than adults. An adult badger weighing 15 kg (33 lb) eats a quantity of food equal to 3.4% of its body weight.[60] Badgers typically eat prey on the spot, and rarely transport it to their setts. Surplus killing has been observed in chicken coops.[47]

Badgers prey on rabbits throughout the year, especially during times when their young are available. They catch young rabbits by locating their position in their nest by scent, then dig vertically downwards to them. In mountainous or hilly districts, where vegetable food is scarce, badgers rely on rabbits as a principal food source. Adult rabbits are usually avoided, unless they are wounded or caught in traps.[63] They consume them by turning them inside out and eating the meat, leaving the inverted skin uneaten.[64] Hedgehogs are eaten in a similar manner.[63] In areas where badgers are common, hedgehogs are scarce.[43] Some rogue badgers may kill lambs[63], though this is very rare; they may be erroneously implicated in lamb killings through the presence of discarded wool and bones near their setts, though foxes, which occasionally live alongside badgers, are often the culprits, as badgers do not transport food to their earths. They typically kill lambs by biting them behind the shoulder[63]. Poultry and game birds are also taken only rarely. Some badgers may build their setts in close proximity to poultry or game farms without ever causing damage. In the rare instances in which badgers do kill reared birds, the killings usually occur in February–March, when food is scarce due to harsh weather and increases in badger populations. Badgers can easily breach bee hives with their jaws, and are mostly indifferent to bee stings, even when set upon by swarms.[63]

Relationships with other non-human predators

European badgers have few natural enemies. While normally docile, Badgers can become extremely aggressive and ferocious when cornered, making it dangerous for predators to target them. Grey wolves (Canis lupus), Eurasian lynxes (Lynx lynx) and brown bears (Ursus arctos), Europe's three largest remaining land predators, and large domestic dogs (C. l. familiaris) can pose a threat to adult badgers, though deaths caused by them are quantitatively rare as these predators are often limited in population due to human persecution and usually prefer easier, larger prey like ungulates, while badgers may fight viciously if aware of a predator and cornered without an escape route.[65][66][68] They may live alongside red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in isolated sections of large burrows.[54] The two species possibly tolerate each other out of commensalism; foxes provide badgers with food scraps, while badgers maintain the shared burrow's cleanliness.[69] However, cases are known of badgers driving vixens from their dens and destroying their litters without eating them.[54] In turn, very large male red foxes are known to have killed badgers in spring.[70] Golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) are known predators of European badgers and attacks by them on badger cubs are not infrequent, including cases where they've been pulled out directly from below the legs of their mothers, and even adult badgers may be attacked by this eagle when emerging weak and hungry from hibernation.[71][72] Eurasian eagle owls (Bubo bubo) may also take an occasional cub and other large raptors such as white-tailed eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla) and greater spotted eagle (Clanga clanga) are considered potential badger cub predators.[65][68][73] Raccoon dogs may extensively use badger setts for shelter. There are many known cases of badgers and raccoon dogs wintering in the same hole, possibly because badgers enter hibernation two weeks earlier than the latter, and leave two weeks later. In exceptional cases, badger and raccoon dog cubs may coexist in the same burrow. Badgers may drive out or kill raccoon dogs if they overstay their welcome.[74]

Status

The International Union for Conservation of Nature rates the European badger as being of least concern. This is because it is a relatively common species with a wide range and populations are generally stable. In Central Europe it has become more abundant in recent decades due to a reduction in the incidence of rabies. In other areas it has also fared well, with increases in numbers in Western Europe and the United Kingdom. However, in some areas of intensive agriculture it has reduced in numbers due to loss of habitat and in others it is hunted as a pest.[1]

Diseases and parasites

Bovine tuberculosis (bovine TB) caused by Mycobacterium bovis is a major mortality factor in badgers, though infected badgers can live and successfully breed for years before succumbing. The disease was first observed in badgers in 1951 in Switzerland where they were believed to have contracted it from chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra) or roe deer (Capreolus capreolus).[75] It was detected in the United Kingdom in 1971 where it was linked to an outbreak of bovine TB in cows. The evidence appears to indicate that the badger is the primary reservoir of infection for cattle in the south west of England, Wales and Ireland. Since then there has been considerable controversy as to whether culling badgers will effectively reduce or eliminate bovine TB in cattle.[76]

Badgers are vulnerable to the mustelid herpesvirus-1, as well as rabies and canine distemper, though the latter two are absent in Great Britain. Other diseases found in European badgers include arteriosclerosis, pneumonia, pleurisy, nephritis, enteritis, polyarthritis and lymphosarcoma.[77]

Internal parasites of badgers include trematodes, nematodes and several species of tapeworm.[77] Ectoparasites carried by them include the fleas Paraceras melis (the badger flea), Chaetopsylla trichosa and Pulex irritans, the lice Trichodectes melis and the ticks Ixodes ricinus, I. canisuga, I. hexagonus, I. reduvius and I. melicula. They also suffer from mange.[77] They spend much time grooming, individuals concentrating on their own ventral areas, alternating one side with the other, while social grooming occurs with one individual grooming another on its dorsal surface. Fleas tried to avoid the scratching, retreating rapidly downwards and backwards through the fur. This was in contrast to fleas away from their host which ran upwards and jumped when disturbed. The grooming seems to disadvantage fleas rather than merely having a social function.[78]

Relationships with humans

In folklore and literature

Badgers play a part in European folklore and are featured in modern literature. In Irish mythology, badgers are portrayed as shape-shifters and kinsmen to Tadg, the king of Tara and foster father of Cormac mac Airt. In one story, Tadg berates his adopted son for having killed and prepared some badgers for dinner.[79] In German folklore, the badger is portrayed as a cautious, peace-loving Philistine, who loves more than anything his home, family and comfort, though he can become aggressive if surprised. He is a cousin of Reynard the Fox, whom he uselessly tries to convince to return to the path of righteousness.[8]

In Kenneth Graham's The Wind in the Willows, Mr. Badger is depicted as a gruff, solitary figure who "simply hates society", yet is a good friend to Mole and Ratty. As a friend of Toad's now-deceased father, he is often firm and serious with Toad, but at the same time generally patient and well-meaning towards him. He can be seen as a wise hermit, a good leader and gentleman, embodying common sense. He is also brave and a skilled fighter, and helps rid Toad Hall of invaders from the wild wood.[80]

The "Frances" series of children's books by Russell and Lillian Hoban depicts an anthropomorphic badger family.

In T.H. White's Arthurian series The Once and Future King, the young King Arthur is transformed into a badger by Merlin as part of his education. He meets with an older badger who tells him "I can only teach you two things – to dig, and love your home." [81]

A villainous badger named Tommy Brock appears in Beatrix Potter's 1912 book The Tale of Mr. Tod. He is shown kidnapping the children of Benjamin Bunny and his wife Flopsy, and hiding them in an oven at the home of Mr. Tod the fox, whom he fights at the end of the book. The portrayal of the badger as a filthy animal which appropriates fox dens was criticized from a naturalistic viewpoint, though the inconsistencies are few and employed to create individual characters rather than evoke an archetypical fox and badger.[82] A wise old badger named Trufflehunter appears in C. S. Lewis' Prince Caspian, where he aids Caspian X in his struggle against King Miraz.[83]

A badger takes a prominent role in Colin Dann's The Animals of Farthing Wood series as second in command to Fox.[84] The badger is also the house symbol for Hufflepuff in the Harry Potter book series.[85] The Redwall series also has the Badger Lords, who rule the extinct volcano fortress of Salamandastron and are renowned as fierce warriors.[86] The children's television series Bodger & Badger was popular on CBBC during the 1990s and was set around the mishaps of a mashed potato-loving badger and his human companion.[87]

An unnamed badger is part of Bosnian writer Petar Kočić's satirical play Badger on Tribunal in which local farmer David Štrbac attempts to sue a badger for eating his crops. It is actually highly critical towards Austro-Hungarian rule in Bosnia and Herzegovina at the beginning of 20th century. In honor of Kočić and his Badger, satirical theater in Banja Luka is named Jazavac (Badger).

Hunting

European badgers are of little significance to hunting economies, though they may be actively hunted locally. Methods used for hunting badgers include catching them in jaw traps, ambushing them at their setts with guns, smoking them out of their earths and through the use of specially bred dogs such as Fox Terriers and Dachshunds to dig them out.[88] Badgers are, however, notoriously durable animals; their skins are thick, loose and covered in long hair which acts as protection, and their heavily ossified skulls allow them to shrug off most blunt traumas, as well as shotgun pellets.[89]

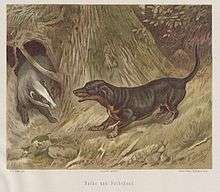

Badger-baiting

Badger-baiting was once a popular blood sport,[90] in which badgers were captured alive, placed in boxes, and attacked with dogs.[91] In the UK, this was outlawed by the Cruelty to Animals Act of 1835[91] and again by the Protection of Animals Act of 1911.[92] Moreover, the cruelty towards and death of the badger constitute offences under the Protection of Badgers Act 1992,[93] and further offences under this act are inevitably committed to facilitate badger-baiting (such as interfering with a sett, or the taking or the very possession of a badger for purposes other than nursing an injured animal to health). If convicted, badger-baiters may face a sentence of up to six months in jail, a fine of up to £5,000, and other punitive measures, such as community service or a ban from owning dogs.[94]

Culling

Many badgers in Europe were gassed during the 1960s and 1970s to control rabies.[95] Until the 1980s, badger culling in the United Kingdom was undertaken in the form of gassing, to control the spread of bovine tuberculosis (bTB). Limited culling resumed in 1998 as part of a 10-year randomized trial cull which was considered by John Krebs and others to show that culling was ineffective. Some groups called for a selective cull,[96] while others favoured a programme of vaccination, and vets support the cull on compassionate grounds as they say that the illness causes much suffering in badgers.[96] In 2012, the government authorized a limited cull[97] led by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), however, this was later deferred with a wide range of reasons given.[98] In August 2013, a full culling programme began where about 5,000 badgers were killed over six weeks in West Somerset and Gloucestershire by marksmen with high-velocity rifles using a mixture of controlled shooting and free shooting (some badgers were be trapped in cages first). The cull caused many protests with emotional, economic and scientific reasons being cited. The badger is considered an iconic species of the British countryside, though is not endangered. It was claimed by shadow ministers that "The government's own figures show it will cost more than it saves...", and Lord Krebs, who led the Randomised Badger Culling Trial in the 1990s, said the two pilots "will not yield any useful information".[99] A scientific study of culling from 2013–2017 has shown a reduction of 36–55% incidence of bovine tuberculosis in cattle.[2]

Tameability

There are several accounts of European badgers being tamed. Tame badgers can be affectionate pets, and can be trained to come to their owners when their names are called. They are easily fed, as they are not fussy eaters, and will instinctively unearth rats, moles and young rabbits without training, though they do have a weakness for pork. Although there is one record of a tame badger befriending a fox, they generally do not tolerate the presence of cats and dogs, and will chase them.[100]

Uses

Badger meat is eaten in some districts of the former Soviet Union, though in most cases it is discarded.[88] Smoked hams made from badgers were once highly esteemed in England, Wales and Ireland.[101]

Some badger products have been used for medical purposes; badger expert Ernest Neal, quoting from an 1810 edition of The Sporting Magazine, wrote;

'The flesh, blood and grease of the badger are very useful for oils, ointments, salves and powders, for shortness of breath, the cough of the lungs, for the stone, sprained sinews, collachs etc. The skin being well dressed is very warm and comfortable for ancient people who are troubled with paralytic disorders.'[101]

The hair of the European badger has been used for centuries for making sporrans[101] and shaving brushes.[90][102] Sporrans are traditionally worn as part of male Scottish highland dress. They form a bag or pocket made from a pelt and a badger or other animal's mask may be used as a flap.[103] The pelt was also formerly used for pistol furniture.[90]

Notes

- Kranz, A.; Abramov, A. V.; Herrero, J. & Maran, T. (2016). "Meles meles". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T29673A45203002.

- Downs SH, Prosser A, Ashton A, Ashfield S, Brunton LA, Brouwer A, Upton P, Robertson A, Donnelly CA, Parry JE (October 2019). "Assessing effects from four years of industry-led badger culling in England on the incidence of bovine tuberculosis in cattle, 2013–2017". Scientific Reports. 9 (14666). doi:10.1038/s41598-019-49957-6. PMC 6789095. PMID 31604960.

- Weiner, E. S. C.; Simpson, J. R. (1989). The Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-861186-2. Retrieved 30 August 2008.

- Neal, Ernest G. and Cheeseman, C. L. (1996) Badgers, p. 2, T. & A.D. Poyser ISBN 0-85661-082-8

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-06-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Ernout, Alfred; Meillet, Antoine (1979) [1932]. Dictionnaire étimologique de la langue latine (in French) (4th ed.). Paris: Klincksieck.

- Devoto, Giacomo (1989) [1979]. Avviamento all'etimologia italiana (in Italian) (6th ed.). Milano: Mondadori.

- Neal 1958, pp. 150–152

- "Badger". Geiriadur: Welsh-English / English-Welsh On-line Dictionary. University of Wales: Trinity Saint David. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Ursus meles". Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. p. 48. (in Latin)

- Kurtén 1968, pp. 103–105

- Spagnesi & De Marina Marinis 2002, pp. 226–227

- Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Species Meles meles". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 611–612. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1253–1254

- Blanford, W. T. (1875). "Description of new Mammalia from Persia and Balúchistán". The Annals and Magazine of Natural History; Zoology, Botany, and Geology. 4. 16 (95): 309–313.

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1254–1255

- Graells, M. de la P. (1897). "Meles Taxus. (Schreb.)". Fauna Mastodológica Ibérica. Memorias de la Real Academia de Ciencias Exactas, Fisicas y Naturales de Madrid. 17. pp. 170–173.

- Miller, G. S. (1907). "Some new European Insectivora and Carnivora". The Annals and Magazine of Natural History; Zoology, Botany, and Geology. 7. 20 (99): 389–398.

- Festa, E. (1914). "Escursioni Zoologiche del Dr. Enrico Festa nell'Isola di Rodi. Mammiferi". Bollettino dei Musei di zoologia ed anatomia comparata della R. Università di Torino. 29 (686): 1–21.

- Heptner, W. G. (1940). "Eine neue Form des Dachses aus Turkestan" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 15: 224.

- Baryshnikov, G. F.; Puzachenko, A. Y.; Abramov, A. V. (2003). "New analysis of variability of check teeth in Eurasian badgers (Carnivora, Mustelidae, Meles)" (PDF). Russian Journal of Theriology. 1 (2): 133–149.

- Raichev, E. (2010). "Adaptability to locomotion in snow conditions of fox, gackal, wild cat, badger in the region of Sredna Gora, Bulgaria". Trakia Journal of Sciences. 8 (2): 499–505.

- Polly, P. D. & MacLeod, N. (2008). "Locomotion in fossil Carnivora: an application of eigensurface analysis for morphometric comparison of 3D surfaces". Palaeontologia Electronica. 11 (2): 10–13.

- Harris & Yalden 2008, p. 427

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1234–1237

- Neal 1958, p. 23

- Pease 1898, p. 24

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1241–1242

- Kowalczyk, R.; Jȩdrzejewska, B.; Zalewski, A. (2003). "Annual and circadian activity patterns of badgers (Meles meles) in Białowieża Primeval Forest (eastern Poland) compared with other Palaearctic populations" (PDF). Journal of Biogeography. 30 (3): 463–472. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.2003.00804.x.

- Delahay, R. J.; Carter, S. P.; Forrester, G. J.; Mitchell, A.; Cheeseman, C. L. (2006). "Habitat correlates of group size, bodyweight and reproductive performance in a high‐density Eurasian badger (Meles meles) population". Journal of Zoology. 270 (3): 437–447. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00165.x.

- Rodriguez, A.; Martin, R.; Delibes, M. (1996). "Space use and activity in a Mediterranean population of badgers Meles meles" (PDF). Acta Theriologica. 41 (1): 59–72.

- Revilla, E.; Palomares, F.; Delibes, M. (2001). "Edge‐core effects and the effectiveness of traditional reserves in conservation: Eurasian badgers in Doñana National Park" (PDF). Conservation Biology. 15 (1): 148–158. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2001.99431.x.

- Wood, G. (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Sterling Pub Co Inc. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 1272

- Neal 1958, p. 25

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 1238

- Harris & Yalden 2008, p. 428

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 1214

- Neal 1958, p. 29

- Pease 1898, p. 29

- Pease 1898, p. 35

- Neal 1958, p. 27

- Macdonald 2001, p. 117

- Harris & Yalden 2008, pp. 430–431

- Schmid, T. K.; Roper, T. J.; Christian, S. E.; Ostler, J.; Conradt, L. & Butler, J. (1993). "Territorial marking with faeces in badgers (Meles meles): a comparison of boundary and hinterland latrine use" (PDF). Behaviour. 127 (3–4): 289–-307.

- Gallagher, J. & Clifton-Hadley, R. S. (2005). "Tuberculosis in badgers; a review of the disease and its significance for other animals" (PDF). Research in Veterinary Science. 69 (3): 203–217.

- Harris & Yalden 2008, p. 432

- Harris & Yalden 2008, p. 431

- König 1973, pp. 162–163

- Harris & Yalden 2008, pp. 433–434

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1278–1279

- Macdonald 2001, p. 116

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1269–1272

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1279–1281

- Neal 1958, p. 83

- Pease 1898, p. 45

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1272–1233

- "Badger: Meles meles". British Wildlife Centre. 2012. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- MacWhite, T., Maher, P., Mullen, E., Marples, N. and Good, M. 2013. Ir. Nat. J. 32: 99 – 105

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1265–1268

- Edwards, Robin. (1980). Social Wasps: Their Biology and Control. W. Sussex, Great Britain: Rentokil Limited.

- Harris & Yalden 2008, pp. 432–433

- Neal 1958, pp. 70–80

- Pease 1898, p. 62

- Sidorovich, V. E., Rotenko, I. I., & Krasko, D. A. (2011, March). Badger Meles meles spatial structure and diet in an area of low earthworm biomass and high predation risk. In Annales Zoologici Fennici (Vol. 48, No. 1, pp. 1–16). Finnish Zoological and Botanical Publishing.

- Olsson, O., Wirtberg, J., Andersson, M., & Wirtberg, I. (1997). Wolf Canis lupus predation on moose Alces alces and roe deer Capreolus capreolus in south-central Scandinavia. Wildlife biology, 3(1), 13–25.

- Butler, J. M., & Roper, T. J. (1995). Escape tactics and alarm responses in badgers Meles meles: a field experiment. Ethology, 99(4), 313-322.

- Dale, Thomas Francis, The fox, Longmans, Green, and Co., 1906

- Palomares, F., & Caro, T. M. (1999). Interspecific killing among mammalian carnivores. The American Naturalist, 153(5), 492–508.

- Watson, J. (2010). The golden eagle. Poyser Monographs; A&C Black.

- Sørensen, O. J., Totsås, M., Solstad, T., & Rigg, R. (2008). Predation by a golden eagle on a brown bear cub. Ursus, 19(2), 190–193.

- Korpimäki, E., & Norrdahl, K. (1989). Avian predation on mustelids in Europe 1: occurrence and effects on body size variation and life traits. Oikos, 205–215.

- Heptner, V. G. ; Naumov, N. P., Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol.II Part 1a, SIRENIA AND CARNIVORA (Sea cows; Wolves and Bears), p. 107, Science Publishers, Inc. USA. 1998, ISBN 1-886106-81-9

- Bouvier, G.; Burgisser, H; Sweitzer, R. (1951). "Tuberculose chez un chamois". Schweizer Arch Tierheil. 93: 689–695.

- Gallagher, J.; Clifton-Hadley, R. S. (2000). "Tuberculosis in badgers; a review of the disease and its significance for other animals" (PDF). Research in Veterinary Science. 69 (3): 203–217. doi:10.1053/rvsc.2000.0422. PMID 11124091.

- Harris & Yalden 2008, p. 435

- Stewart, Paul D.; Macdonald, David W. (2003). "Badgers and Badger Fleas: Strategies and Counter-Strategies". Ethology. 109 (9): 751–763. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0310.2003.00910.x.

- Monaghan, Patricia, The encyclopedia of Celtic mythology and folklore, p.436, Infobase Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8160-4524-0

- Grahame, Kenneth (1908). The Wind in the Willows. Wordsworth Editions Ltd. ISBN 978-1853260179.

- White, T.H. (1939) 'The Once And Future King.' 200 Madison Ave., New York, NY 10016.

- MacDonald, Ruth K., Beatrix Potter, p.47, Twayne Publishers, 1986, ISBN 0-8057-6917-X

- C.S., Lewis (1951). Prince Caspian. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0006716792.

- Dann, Colin (1979). The Animals of Farthing Wood. Egmont Publishing. ISBN 1-4052-2552-1.

- Rowling, J. K. (1997). Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone. Bloomsbury. ISBN 0-7475-3269-9.

- Jacques, Brian (2001). Tribes of Redwall: Badgers. Red Fox. ISBN 0-09-941714-6.

- "Comedy: Bodger and Badger". BBC. Retrieved 2013-06-20.

- Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1281–1282

- Pease 1898, p. 36

- EB (1878).

- EB (1911).

- "Protection of Animals Act 1911 (revised)". OPSI website. Archived from the original on 2009-05-01. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- UK Government. "Protection of Badgers Act 1992". Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- "Protection of Badgers Act 1992". OPSI website. Archived from the original on 2009-08-14. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- The European badger (Meles meles) Archived 2012-09-01 at the Wayback Machine. badger.org.uk

- Moody, Oliver (2013-04-27). "Badger cull is necessary to stop them suffering, say vets". The Times: Wildlife. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- Carrington, D. (2011-12-11). "Badger culling will go ahead in 2012". The Guardian. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- Carrington, D. (2012). "Badger cull postponed until 2013". The Guardian. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- "Badger cull begins in Somerset in attempt to tackle TB". BBC. 2013. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- Pease 1898, pp. 58–61

- Neal 1958, pp. 152–154

- Griffiths, H.I.; Thomas, D.H. (1997). The Conservation and Management of the European Badger (Meles Meles). Strasbourg: Council of Europe. p. 53. ISBN 978-9-28-713447-9.

- "Sporran wearers may need licence". BBC News. 2007-06-24. Retrieved 2013-07-11.

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), , Encyclopædia Britannica, 3 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 188

- Harris, S.; Yalden, D. (2008). Mammals of the British Isles (Forth Revised ed.). Mammal Society. ISBN 0-906282-65-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kurtén, B. (1968). "The Badger Meles meles Linné". Pleistocene mammals of Europe (Reprint 2017 ed.). London and New York: Routledge. pp. 104–105. ISBN 9781351499484.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heptner, V. G.; Sludskii, A. A. (2001). "Badger Meles meles Linnaeus, 1758". Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 1b, Carnivores (Mustelidae and Procyonidae). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Libraries and National Science Foundation. pp. 1232–1282. ISBN 90-04-08876-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- König, C. (1973). Mammals. London: William Collins. ISBN 0-00-212080-1.

- Macdonald, D. (2001). The New Encyclopedia of Mammals. ISBN 0-19-850823-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Neal, E. (1976). The Badger. New Naturalist (Fifth ed.). London: Collins. ISBN 9780002193993.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pease, A. E. (1898). The badger; a monograph. London: Lawrence and Bullen.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spagnesi, M.; De Marina Marinis, M. (2002). Mammiferi d'Italia (PDF) (in Italian). Quaderni di Conservazione della Natura. ISSN 1592-2901.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Ernest Neal & Chris Cheeseman. Badgers (Poyser, 2002)

- Richard Meyer. The Fate of the Badger (Batsford 1986), Reprinted with new material (Fire-raven Writing, 2016)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Meles meles. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Meles meles |

- ARKive Photographs and video

- The Badger Trust – representing over 80 British badger groups

- Scottish Badgers

- Steve Jackson's Badger Pages – Facts about and photos of the badgers of the world

- Badgerland – The Definitive On-Line Guide to Badgers (Meles meles) in the UK

- Badgerwatcher.com – A guide to watching badgers in the UK

- Wildlife Online – Natural History of the European Badger

- http://durhambadgers.org.uk/page.php?pageid=1

- Lancashire Badger Group.

- Dublin and Wicklow Badger Group

- Science & Nature: Animals, BBC.

- Badgers in the Netherlands, Badgergroup Brabant Foundation.

- Badger Survey in the Netherlands 2000–2001, The Census Foundation.

- Waarneming.nl Originally a Dutch site, but you can change language at the top of the page. Sightings, pictures and distribution maps of European badgers in the Netherlands.

- Badgers in France, L'assiociation Meles.

- A video of an adult european badger. This is a close up video showing their behavior

- Video of a European Badger feeding on peanuts by its sett

- Video of an evening's badger-watching in mid-Wales, U.K.

- Badgers and TB in the UK

- DEFRA (UK government department) position on badgers and TB

- Executive summary of the Krebs Report Bovine Tuberculosis in Cattle and Badgers 1997

- The Randomised Badger Culling Trial

- Godfray Report, Independent Scientific Review of the Randomised Badger Culling Trial and Associated Epidemiological Research, March 2004. PDF format

- National Farmers Union proposals to control badgers (would involve repeal of the 1992 act) July 2005

- NFBG (now Badger Trust) response to the National Farmers Union proposals, August 2005

- Claims of continued badger-hunting in the UK

- Allegations of lamping (among other practices) were made in the appendix to the NFBG (now Badger Trust) response to the Krebs Report