Sun bear

The sun bear (Helarctos malayanus) is a bear species occurring in tropical forest habitats of Southeast Asia. It is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. The global population is thought to have declined by more than 30% over the past three bear generations. Suitable habitat has been dramatically reduced due to the large-scale deforestation that has occurred throughout Southeast Asia over the past three decades.[1]

| Sun bear | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Ursidae |

| Subfamily: | Ursinae |

| Genus: | Helarctos Horsfield, 1825 |

| Species: | H. malayanus |

| Binomial name | |

| Helarctos malayanus (Raffles, 1821) | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

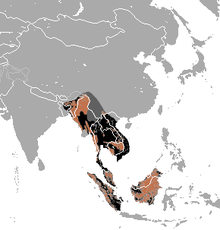

| Sun bear range (brown – extant, black – former, dark grey – presence uncertain) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Ursus malayanus Raffles, 1821 | |

The sun bear is also known as the "honey bear", which refers to its voracious appetite for honeycombs and honey.[2] However, "honey bear" can also refer to a kinkajou, which is an unrelated member of the Procyonidae.

Characteristics

The sun bear's fur is usually jet-black, short, and sleek with some under-wool; some individual sun bears are reddish or grey.[3] Two whirls occur on the shoulders, from where the hair radiates in all directions. A crest is seen on the sides of the neck and a whorl occurs in the centre of the breast patch. Always, a more or less crescent-shaped pale patch is found on the breast that varies individually in colour ranging from buff, cream, or dirty white to ochreous. The skin is naked on the upper lip. The tongue is long and protrusible. The ears are small and round, broad at the base, and capable of very little movement. The front legs are somewhat bowed with the paws turned inwards, and the claws are cream.[4]

The sun bear is the smallest of the bear species. Adults are about 120–150 cm (47–59 in) long and weigh 27–80 kg (60–176 lb). Males are 10–20% larger than females. Their muzzles are short and light-coloured, and in most cases, the white area extends above the eyes. Their paws are large, and the soles are fur-less, which is thought to be an adaptation for climbing trees. Their claws are large, curved, and pointed.[3][5][6] The sun bear's claws are sickle-shaped; the front paw claws are long and heavy. The tail is 30–70 mm (1.2–2.8 in) long.[7]

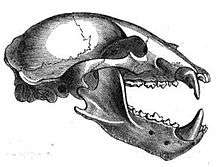

During feeding, the sun bear can extend its exceptionally long tongue 20–25 cm (7.9–9.8 in) to extract insects and honey.[8] The sun bear's teeth are very large, especially canines, and high bite forces in relation to its body size, which are not well understood, but could be related to its frequent opening of tropical hardwood trees (with its powerful jaws and claws) in pursuit of insects, larvae, or honey.[9] The animal's entire head is also large, broad, and heavy in proportion to the body, and the palate is wide in proportion to the skull. The overall morphology of this bear (inward-turned front feet, ventrally flattened chest, powerful forelimbs with large claws) indicates adaptation for extensive climbing.[3]

Distribution and habitat

Sun bears are found in the tropical rainforest of Southeast Asia ranging from northeastern India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, Peninsular Malaysia, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam to southern Yunnan Province in China, and on the islands of Sumatra and Borneo in Indonesia. They now occur very patchily through much of their former range, and have been extirpated from many areas, especially in mainland Southeast Asia. Their current distribution in eastern Myanmar and most of Yunnan is unknown.[1] The bear's habitat is associated with tropical evergreen forests.[10]

Distribution of subspecies

- The Malayan sun bear (H. m. malayanus (Raffles, 1821)) occurs on the Asian mainland and Sumatra.[11]

- The Bornean sun bear (H. m. euryspilus (Horsfield, 1825)) occurs only on the island of Borneo.[12]

Helarctos anmamiticus, described by Pierre Marie Heude in 1901 from Annam, is not considered a distinct species, but is subordinated (a junior synonym) to H. m. malayanus.[11]

Ecology and behavior

As sun bears occur in tropical regions with year-round available foods, they do not hibernate. Except for females with their offspring, they are usually solitary.[1] Male sun bears are primarily diurnal, but some are active at night for short periods. Bedding sites consist mainly of fallen hollow logs, but they also rest in standing trees with cavities, in cavities underneath fallen logs or tree roots, and in tree branches high above the ground.[13]

In captivity, they exhibit social behavior, and sleep mostly during the day.[14]

Sun bears are known as very fierce animals when surprised in the forest.[3]

Diet

Bees, beehives, and honey are important food items of sun bears.[2] They are omnivores, feeding primarily on termites, ants, beetle larvae, bee larvae and a large variety of fruit species, especially figs when available. They have been observed eating fruits from the durian species Durio graveolens.[15] Occasionally, growth shoots of certain palms and some species of flowers are consumed, but otherwise vegetative matter appears rare in the diet. In the forests of Kalimantan, fruits of Moraceae, Burseraceae and Myrtaceae make up more than 50% of the fruit diet.[6] They are known to tear open trees with their long, sharp claws and teeth in search of wild bees and leave behind shattered tree trunks.[16]

Sun bear scats collected in a forest reserve in Sabah contained mainly invertebrates such as beetles and their larvae, termites, and ants, followed by fruits and vertebrates. They break open decayed wood in search of termites, beetle larvae, and earthworms, and use their claws and teeth to break the standing termite mound into a few pieces. They quickly lick and suck the contents from the exposed mound, and also hold pieces of the broken mound with their front paws, while licking the termites from the surface of the mound. They consume figs in large amounts and eat them whole. Vertebrates consumed comprise birds, eggs, reptiles, turtles, deer and several unidentified small vertebrates.[17] Hair or bone remains are rarely found in sun bear scat.[18]

They can crack open nuts with their powerful jaws. Much of their food must be detected using their keen sense of smell.

Reproduction

Females are observed to mate at about 3 years of age. During time of mating, the sun bear shows behaviours such as hugging, mock fighting, and head bobbing with its mate.

Gestation has been reported at 95 and 174 days. Litters consist of one or two cubs weighing about 280–325 g (9.9–11.5 oz) each.[5][19] Cubs are born blind and hairless. Initially, they are totally dependent on their mothers, and suckle for about 18 months. After one to three months, the young can run, play, and forage near their mothers. They reach sexual maturity after 3–4 years, and may live up to 30 years in captivity.

Threats

The two major threats to sun bears are habitat loss and commercial hunting. These threats are not evenly distributed throughout their range. In areas where deforestation is actively occurring, they are mainly threatened by the loss of forest habitat and forest degradation arising from clear-cutting for plantation development, unsustainable logging practices, illegal logging both within and outside protected areas, and forest fires.[1]

The main predator of sun bears throughout its range by far is man. Commercial poaching of bears for the wildlife trade is a considerable threat in most countries. During surveys in Kalimantan between 1994 and 1997, interviewees admitted to hunting sun bears and indicated that sun bear meat is eaten by indigenous people in several areas in Kalimantan. High consumption of bear parts was reported to occur where Japanese or Korean expatriate employees of timber companies created a temporary demand. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) shops in Sarawak and Sabah offered sun bear gallbladders. Several confiscated sun bears indicated that live bears are also in demand for the pet trade.[20]

Sun bears are among the three primary bear species specifically targeted for the bear bile trade in Southeast Asia, and are kept in bear farms in Laos, Vietnam, and Myanmar. Bear bile products include raw bile sold in vials, gall bladder by the gram or in whole form, flakes, powder and pills. The commercial production of bear bile from bear farming has turned bile from a purely traditional medicinal ingredient to a commodity with bile now found in non-TCM products like cough drops, shampoo, and soft drinks.[21]

Tigers and other large cats are potential predators.[22][23] The loose skin, particularly around the neck, is an evolutionary trait and defense mechanism. If caught by a predator, the loose skin would allow the sun bear to spin its head around to try and bite its attacker.[23] American Museum of Natural History naturalist and co-founder Albert S. Bickmore described a case in which a tiger-sun bear interaction resulted in a prolonged altercation and in the death of both animals.[24] A wild female sun bear was swallowed by a large reticulated python in a lowland dipterocarp forest in East Kalimantan. The python possibly had come across the sleeping bear. Other predators on mainland Southeast Asia and Sumatra could be the leopard and the clouded leopard, although the latter could be too small to kill an adult sun bear.[25]

Conservation

Helarctos malayanus has been listed on CITES Appendix I since 1979. Killing of sun bears is strictly prohibited under national wildlife protection laws throughout their range. However, little enforcement of these laws occurs.[1]

In captivity

The Malayan sun bear is part of an international captive-breeding program and has a Species Survival Plan under the Association of Zoos and Aquariums since late 1994.[19] Since that same year, the European breed registry for sun bears is kept in the Cologne Zoological Garden, Germany.[26]

Comprehensive research about sun bear conservation and rehabilitation is the mission of the Bornean Sun Bear Conservation Centre in Sandakan, Sabah, founded in 2008 by wildlife biologist Wong Siew Te.

Gallery

Malayan sun bear at the Columbus Zoo

Malayan sun bear at the Columbus Zoo A juvenile sun bear at the Bornean Sun Bear Conservation Centre, Malaysia

A juvenile sun bear at the Bornean Sun Bear Conservation Centre, Malaysia- Three sun bears at the Medan old zoo in Jalan Brigjen Katamso, Medan, North Sumatra, Indonesia.

References

- Scotson, L.; Fredriksson, G.; Augeri, D.; Cheah, C.; Ngoprasert, D. & Wai-Ming, W. (2017). "Helarctos malayanus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T9760A123798233.

- Lekagul, B. and J. A. McNeely (1977). Mammals of Thailand. Kurusapha Ladprao Press, Bangkok.

- Servheen, C.; Salter, R. E. (1999). "Chapter 11: Sun Bear Conservation Action Plan" (PDF). In Servheen, C.; Herrero, S.; Peyton, B. (eds.). Bears: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Gland: International Union for Conservation of Nature. pp. 219–224.

- Pocock, R. I. (1941). The fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Mammalia. – Volume 2. Taylor and Francis, London.

- Malayan Sun Bear Archived 2014-12-21 at the Wayback Machine, Arkive

- Servheen, C. (1993). The Sun Bear. Pp. 124 in: Stirling, I., Kirshner, D., Knight, F. (eds.). Bears, Majestic Creatures of the Wild. Rodale Press, Emmaus, Pennsylvania.

- Brown, G. (1996). Great Bear Almanac. The Lyons Press. p. 340. ISBN 978-1-55821-474-3.

- Meijaard, E. (1997). The Malayan Sun Bear on Borneo, with Special Emphasis on its Conservation Status in Kalimantan, Indonesia. International Ministry of Forestry – Tropendos Kalimantan Project and World Society for the Protection of Animals, London.

- Christiansen, P (2007). "Evolutionary implications of bite mechanics and feeding ecology in bears". Journal of Zoology. 272 (4): 423–443. Bibcode:2010JZoo..281..263G. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00286.x.

- Nazeri, Mona; Jusoff K; Madani N; Mahmud AR; Bahman AR; et al. (2012). "Predictive Modeling and Mapping of Malayan Sun Bear (Helarctos malayanus) Distribution Using Maximum Entropy". PLOS ONE. 7 (10): e48104. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...748104N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048104. PMC 3480464. PMID 23110182.

- Ellerman, J. R., Morrison-Scott, T. C. S. (1966). Checklist of Palaearctic and Indian mammals 1758 to 1946. Second edition. British Museum of Natural History, London. p. 241.

- Meijaard, E. (2004). "Craniometric differences among Malayan sun bears (Ursus malayanus); Evolutionary and taxonomic implications". Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 52: 665–672.

- Wong, S. T.; Servheen, C. W.; Ambu, L. (2004). "Home range, movement and activity patterns, and bedding sites of Malayan sun bears Helarctos malayanus in the Rainforest of Borneo" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 119 (2): 169–181. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2003.10.029. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-11. Retrieved 2013-02-07.

- Wong, S. T (2011). "The Integration of Fulung and Mary". Borneo Sun Bear Conservation Center. Archived from the original on 2014-04-24. Retrieved 2012-09-11.

- Fredriksson, Gabriella M.; Wich, Serge A.; Trisno (1 November 2006). "Frugivory in sun bears (Helarctos malayanus) is linked to El Niño-related fluctuations in fruiting phenology, East Kalimantan, Indonesia". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 89 (3): 489–508. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2006.00688.x. ISSN 1095-8312.

Durio graveolens Bombacaceae S fr Tree

- MacKinnon, K., Hattah, G., Halim, H., Mangalik, A. (1996). The ecology of Kalimantan, Indonesia Borneo. Periplus Editions, Hong Kong.

- Wong, S. T.; Servheen C.; Ambu, L. (2002). "Food habits of Malayan Sun Bears in lowland tropical forests of Borneo" (PDF). Ursus. 13: 127–136.

- Augeri, D. M. (2005). On the Biogeographic Ecology of the Malayan Sun Bear. PhD dissertation, Darwin College, Cambridge.

- Ball, J. (2000). Sun Bear Fact Sheet. Woodland Park Zoo.

- Meijaard, E. (1999). Human imposed threats to sun bears in Borneo. Ursus 11: 185–192.

- Foley, K. E., Stengel, C. J. and Shepherd, C. R. (2011). Pills, Powders, Vials and Flakes: the bear bile trade in Asia. Traffic Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia.

- Kawanishi, K.; Sunquist, M. E. (2004). "Conservation status of tigers in a primary rainforest of Peninsular Malaysia". Biological Conservation. 120 (3): 329–344. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2004.03.005.

- A-Z-Animals.com. "Sun Bear". a-z-animals.com. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- Bickmore, Albert Smith. Travels in the East Asian Archipelago. London: John Murray; 1868. pp510-1. Accessed at: https://books.google.com/books?id=PAlJAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA510&lpg=PA510&dq=sun+bear+tiger+travels+in+the+archipelago&source=bl&ots=PWZxeOlNd3&sig=dBxYegZDpKLcBUGQ1DNDBQUwsaE&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0CB4Q6AEwAGoVChMI2ZLT9fWHxgIV0j2MCh07Mw50#v=onepage&q=sun%20bear%20tiger%20travels%20in%20the%20archipelago&f=false

- Fredriksson, G. M. (2005). "Predation on Sun Bears by Reticulated Python in East Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo" (PDF). Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. 53 (1): 165–168. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-08-11.

- Kok, J. (ed.) (2008). EAZA Bear TAG Annual Report 2007–2008. European Association of Zoos and Aquaria, Amsterdam.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikispecies has information related to Helarctos malayanus |