Caracal

The caracal /ˈkærəkæl/ (Caracal caracal) is a medium-sized wild cat native to Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia and India. It is characterised by a robust build, long legs, a short face, long tufted ears, and long canine teeth. Its coat is uniformly reddish tan or sandy, while the ventral parts are lighter with small reddish markings. It reaches 40–50 cm (16–20 in) at the shoulder and weighs 8–18 kg (18–40 lb). It was first scientifically described by German naturalist Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber in 1776. Three subspecies are recognised since 2017.

| Caracal | |

|---|---|

%2C_Paris%2C_d%C3%A9cembre_2013.jpg) | |

| Caracal at Jardin des Plantes, Paris | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Felinae |

| Genus: | Caracal |

| Species: | C. caracal |

| Binomial name | |

| Caracal caracal (Schreber, 1776) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

See text | |

| |

| Distribution of Caracal, 2016[1] | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Typically nocturnal, the caracal is highly secretive and difficult to observe. It is territorial, and lives mainly alone or in pairs. The caracal is a carnivore that typically preys upon small mammals, birds, and rodents. It can leap higher than 4 m (12 ft) and catch birds in midair. It stalks its prey until it is within 5 m (16 ft) of it, after which it runs it down and kills its prey with a bite to the throat or to the back of the neck. Both sexes become sexually mature by the time they are one year old and breed throughout the year. Gestation lasts between two and three months, resulting in a litter of one to six kittens. Juveniles leave their mothers at the age of nine to ten months, though a few females stay back with their mothers. The average lifespan of captive caracals is nearly 16 years.

Caracals have been tamed and used for hunting since the time of ancient Egypt.[3][4]

Taxonomy and phylogeny

Felis caracal was the scientific name used by Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber in 1776 who described a caracal skin from the Cape of Good Hope.[5] In 1843, British zoologist John Edward Gray placed it in the genus Caracal. It is placed in the family Felidae and subfamily Felinae.[2]

In the 19th and 20th centuries, several caracal specimens were described and proposed as subspecies. Since 2017, three subspecies are recognised as valid:[6]

- Southern caracal (C. c. caracal) (Schreber, 1776) – occurs in Southern and East Africa

- Northern caracal (C. c. nubicus) (Fischer, 1829)[7] – occurs in North and West Africa

- Asiatic caracal (C. c. schmitzi) (Matschie, 1912)[8] – occurs in Asia

Phylogeny

Results of a phylogenetic study indicates that the caracal and the African golden cat (Caracal aurata) diverged between 2.93 and 1.19 million years ago. These two species together with the serval (Leptailurus serval) form the Caracal lineage, which diverged between 11.56 and 6.66 million years ago.[9][10] The ancestor of this lineage arrived in Africa between 8.5 and 5.6 million years ago.[11]

The relationship of the caracal is considered as follows:[9][10]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Etymology

The name 'caracal' is composed of two Turkish words: 'kara', meaning black, and 'kulak', meaning ear. The first recorded use of this name dates back to 1760.[12] An alternative name for the caracal is Persian lynx.[13] The 'lynx' of the Greeks and Romans was most probably the caracal and the name 'lynx' is sometimes still applied to it, but the present-day lynx proper is a separate species.[14]

Local names

In Tigrinya language: ጭክ ኣንበሳ ch’ok anbessa, which means bearded lion.[15]

Characteristics

The caracal is a slender, moderately sized cat characterised by a robust build, a short face, long canine teeth, tufted ears, and long legs. It reaches nearly 40–50 cm (16–20 in) at the shoulder; the head-and-body length is typically 78 cm (31 in) for males and 73 cm (29 in) for females. While males weigh 12–18 kg (26–40 lb), females weigh 8–13 kg (18–29 lb). The tan, bushy tail measures 26–34 cm (10–13 in), and extends to the hocks.[16][17] The caracal is sexually dimorphic; the females are smaller than the males in most bodily parameters.[18]

The prominent facial features include the 4.5-cm-long black tufts on the ears, two black stripes from the forehead to the nose, the black outline of the mouth, the distinctive black facial markings, and the white patches surrounding the eyes and the mouth. The eyes appear to be narrowly open due to the lowered upper eyelid, probably an adaptation to shield the eyes from the sun's glare. The ear tufts may start drooping as the animal ages. The coat is uniformly reddish tan or sandy, though black caracals are also known. The underbelly and the insides of the legs are lighter, often with small reddish markings.[18] The fur, soft, short, and dense, grows coarser in the summer. The ground hairs (the basal layer of hair covering the coat) are denser in winter than in summer. The length of the guard hairs (the hair extending above the ground hairs) can be up to 3 cm (1.2 in) long in winter, but shorten to 2 cm (0.8 in) in summer.[19] These features indicate the onset of moulting in the hot season, typically in October and November.[20] The hind legs are longer than the forelegs, so the body appears to be sloping downward from the rump.[17][18]

Caracals possess distinctive black markings on their faces, and some individuals may have pronounced 'eyebrow' markings.

The caracal is often confused with the lynx, as both cats have tufted ears. However, a notable point of difference between the two is that the lynx is spotted and blotched, while the caracal shows no such markings on the coat.[18] The African golden cat has a similar build as the caracal's, but is darker and lacks the ear tufts. The sympatric serval can be distinguished from the caracal by the former's lack of ear tufts, white spots behind the ears, spotted coat, longer legs, longer tail, and smaller footprints.[19][21]

The skull of the caracal is high and rounded, featuring large auditory bullae, a well-developed supraoccipital crest normal to the sagittal crest, and a strong lower jaw. The caracal has a total of 30 teeth; the dental formula is 3.1.3.13.1.2.1. The deciduous dentition is 3.1.23.1.2. The striking canines are up to 2 cm (0.8 in) long, heavy, and sharp; these are used to give the killing bite to the prey. The caracal lacks the second upper premolars, and the upper molars are diminutive.[20] The large paws, similar to those of the cheetah,[22] consist of four digits in the hind legs and five in the fore legs.[19] The first digit of the fore leg remains above the ground and features the dewclaw. The claws, sharp and retractable (able to be drawn in), are larger but less curved in the hind legs.[19]

Distribution and habitat

In Africa, the caracal is widely distributed south of the Sahara, but considered rare in North Africa. In Asia, it occurs from the Arabian Peninsula, Middle East, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan to western India.[1] It inhabits forests, savannas, marshy lowlands, semideserts, and scrub forests, but prefers dry areas with low rainfall and availability of cover. In montane habitats such as the Ethiopian Highlands, it occurs up to an altitude of 3,000 m (9,800 ft).[19]

In Benin's Pendjari National Park, caracals were recorded by camera-traps in 2014 and 2015.[23] In Ethiopia, such as in the Degua Tembien massif, they can be seen along roads, sometimes as road kills.[24]

In the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, a male caracal was recorded by camera-traps in Jebel Hafeet National Park in the Al-Ain Region, Abu Dhabi in February 2019, the first such record since 1984.[25][26]

In Uzbekistan, caracals were recorded only in the desert regions of the Ustyurt Plateau and Kyzylkum Desert. Between 2000 and 2017, 15 individuals were sighted alive, and at least 11 were killed by herders.[27]

In India, the caracal occurs in Sariska Tiger Reserve and Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve.[28][29]

Ecology and behaviour

.jpg)

The caracal is typically nocturnal (active at night), though some activity may be observed during the day as well. However, the cat is so secretive and difficult to observe that its activity at daytime might easily go unnoticed.[20] A study in South Africa showed that caracals are most active when the air temperature drops below 20 °C (68 °F); activity typically ceases at higher temperatures.[30] A solitary cat, the caracal mainly occurs alone or in pairs; the only groups seen are of mothers with their offspring.[17] Females in oestrus temporarily pair with males. A territorial animal, the caracal marks rocks and vegetation in its territory with urine and probably with dung, which is not covered with soil. Claw scratching is prominent, and dung middens are typically not formed.[19] In Israel, males are found to have territories averaging 220 km2 (85 sq mi), while that of females averaged 57 km2 (22 sq mi). The male territories vary from 270–1,116 km2 (104–431 sq mi) in Saudi Arabia. In Mountain Zebra National Park (South Africa), the female territories vary between 4.0 and 6.5 km2 (1.5 and 2.5 sq mi). These territories overlap extensively.[18] The conspicuous ear tufts and the facial markings often serve as a method of visual communication; caracals have been observed interacting with each other by moving the head from side to side so that the tufts flicker rapidly. Like other cats, the caracal meows, growls, hisses, spits, and purrs.[17]

Diet and hunting

A carnivore, the caracal typically preys upon small mammals, birds, and rodents. Studies in South Africa have reported that it preys on the Cape grysbok, the common duiker, sheep, goats, bush vlei rats, rock hyraxes, hares, and birds.[31][32][33] A study in western India showed that rodents comprise a significant portion of the diet.[28] They will feed from a variety of sources, but tend to focus on the most abundant one.[34] Grasses and grapes are taken occasionally to clear their immune system and stomach of any parasites.[35] Larger antelopes such as young kudu, bushbuck, impala, mountain reedbuck, and springbok may also be targeted. Mammals generally comprise at least 80% of the diet.[19] Lizards, snakes, and insects are infrequently eaten.[1] They are notorious for attacking livestock, but rarely attack humans.[22]

Its speed and agility make it an efficient hunter, able to take down prey two to three times its size.[1] The powerful hind legs allow it to leap more than 3 m (10 ft) in the air to catch birds on the wing.[18][36][37] It can even twist and change its direction mid-air.[18] It is an adroit climber.[18] It stalks its prey until it is within 5 m (16 ft), following which it can launch into a sprint. While large prey such as antelopes are suffocated by a throat bite, smaller prey are killed by a bite on the back of the neck.[18] Kills are consumed immediately, and less commonly dragged to cover. It returns to large kills if undisturbed.[19] It has been observed to begin feeding on antelope kills at the hind parts.[20] It may scavenge at times, though this has not been frequently observed.[31] It often has to compete with foxes, wolves, leopards, and hyaena for prey.[22]

Reproduction

Both sexes become sexually mature by the time they are a year old; production of gametes begins even earlier at seven to ten months. However, successful mating takes place only at 12 to 15 months. Breeding takes place throughout the year. Oestrus, one to three days long, recurs every two weeks unless the female is pregnant. Females in oestrus show a spike in urine-marking, and form temporary pairs with males. Mating has not been extensively studied; a limited number of observations suggest that copulation, that lasts nearly four minutes on an average, begins with the male smelling the areas urine-marked by the female, which rolls on the ground. Following this, he approaches and mounts the female. The pair separate after copulation.[18][19]

Gestation lasts about two to three months, following which a litter consisting of one to six kittens is born. Births generally peak from October to February. Births take place in dense vegetation or deserted burrows of aardvarks and porcupines. Kittens are born with their eyes and ears shut and the claws not retractable (unable to be drawn inside); the coat resembles that of adults, but the abdomen is spotted. Eyes open by ten days, but it takes longer for the vision to become normal. The ears become erect and the claws become retractable by the third or the fourth week. Around the same time, the kittens start roaming their birthplace, and start playing among themselves by the fifth or the sixth week. They begin taking solid food around the same time; they have to wait for nearly three months before they make their first kill. As the kittens start moving about by themselves, the mother starts shifting them every day. All the milk teeth appear in 50 days, and permanent dentition is completed in 10 months. Juveniles begin dispersing at nine to ten months, though a few females stay back with their mothers. The average lifespan of the caracal in captivity is nearly 16 years.[18][22][38]

In the 1990s, a captive caracal spontaneously mated with a domestic cat in the Moscow Zoo, resulting in a felid hybrid offspring.[39]

Threats

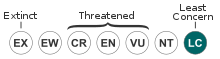

The caracal is listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List since 2002, as it is widely distributed in over 50 range countries, where the threats to caracal populations vary in extent. Habitat loss due to agricultural expansion, the building of roads and settlements is a major threat in all range countries. It is thought to be close to extinction in North Africa, Critically Endangered in Pakistan, Endangered in Jordan, but stable in central and Southern Africa. Local people kill caracal to protect livestock, or in retaliation for its preying on small livestock. Additionally, it is threatened by hunting for the pet trade on the Arabian Peninsula. In Turkey and Iran, caracals are frequently killed in road accidents.[1] In Uzbekistan, the major threat to caracal is killing by herders in retaliation for livestock losses. Guarding techniques and sheds are inadequate to protect small livestock like goats and sheep from being attacked by predators. Additionally, similarly to Ethiopia, heavy-traffic roads crossing Caracal habitat pose a potential threat for the species.[27]

Conservation

African caracal populations are listed under CITES Appendix II, while Asian populations come under CITES Appendix I. Hunting of caracal is prohibited in Afghanistan, Algeria, Egypt, India, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan, Syria, Tajikistan, Tunisia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. In Namibia and South Africa, it is considered a "problem animal", and its hunting is allowed for protecting livestock. Caracals occur in a number of protected areas across their range.[1]

The Central Asian caracal population is listed as Critically Endangered in Uzbekistan since 2009, and in Kazakhstan since 2010.[27][40][41]

In culture

Chinese emperors used caracals as gifts. In the 13th and the 14th centuries, Yuan dynasty rulers bought numerous caracals, cheetahs, and tigers from Muslim merchants in the western parts of the empire in return for gold, silver, cash, and silk. According to the Ming Shilu, the subsequent Ming dynasty continued this practice. Until as recently as the 20th century, the caracal was used in hunts by Indian rulers to hunt small game, while the cheetah was used for larger game.[42] In those times, caracals were exposed to a flock of pigeons and people would bet on which caracal would kill the largest number of pigeons. This probably gave rise to the expression "to put the cat among the pigeons".[37]

The caracal appears to have been religiously significant in the Egyptian culture, as it occurs in paintings and as bronze figurines; sculptures were believed to guard the tombs of pharaohs. Embalmed caracals have also been discovered. Its pelt was used for making fur coats.[22]

References

- Avgan, B.; Henschel, P. & Ghoddousi, A. (2016). "Caracal caracal". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T3847A102424310.

- Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 533. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Faure, E.; Kitchener, A. C. (2009). "An archaeological and historical review of the relationships between felids and people". Anthrozoös. 22 (3): 221–238. doi:10.2752/175303709X457577.

- Malek, J. (1997). The cat in ancient Egypt. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Schreber, J. C. D. (1777). "Der Karakal". Die Säugethiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur mit Beschreibungen. Erlangen: Wolfgang Walther. pp. 413–414.

- Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z.; Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News. Special Issue 11: 30−31.

- Fischer, J. B. (1829). "F. caracal Schreb.". Synopsis Mammalium. Stuttgart: J. G. Cottae. p. 210.

- Matschie, P. (1912). "Über einige Rassen des Steppenluchses Felis (Caracal) caracal (St. Müll.)". Sitzungsberichte der Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin. 1912 (2a): 55–67.

- Johnson, W. E.; Eizirik, E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Murphy, W. J.; Antunes, A.; Teeling, E.; O'Brien, S. J. (2006). "The late Miocene radiation of modern Felidae: A genetic assessment". Science. 311 (5757): 73–77. Bibcode:2006Sci...311...73J. doi:10.1126/science.1122277. PMID 16400146.

- Werdelin, L.; Yamaguchi, N.; Johnson, W. E.; O'Brien, S. J. (2010). "Phylogeny and evolution of cats (Felidae)". In Macdonald, D. W.; Loveridge, A. J. (eds.). Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 59–82. ISBN 978-0-19-923445-5.

- Johnson, W. E.; O'Brien, S. J. (1997). "Phylogenetic reconstruction of the Felidae using 16S rRNA and NADH-5 mitochondrial genes". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 44 (Supplement 1): S98–S116. Bibcode:1997JMolE..44S..98J. doi:10.1007/PL00000060. PMID 9071018.

- "Caracal". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- Chisholm, H.; Phillips, W. A., eds. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed, Vol. V. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 297–298.

- Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878). . Encyclopædia Britannica, 9th ed, Vol. V. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 80–81.

- Aerts, R. (2019). "Forest and woodland vegetation in the highlands of Dogu'a Tembien". In Nyssen J.; Jacob, M.; Frankl, A. (eds.). Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains: The Dogu'a Tembien District. Springer International Publishing. ISBN 9783030049546.

- Nowak, R. M. (1999). "Caracal". Walker's Mammals of the World (Sixth ed.). Baltimore, Maryland, US: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 810–811. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- Estes, R. D. (2004). "Caracal". The Behavior Guide to African Mammals: Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, Primates (Fourth ed.). Berkeley, California, US: University of California Press. pp. 363–365. ISBN 978-0520-080-850.

- Sunquist, F. & Sunquist, M. (2002). "Caracal Caracal caracal". Wild Cats of the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 38–43. ISBN 978-0-226-77999-7.

- Kingdon, J. (1997). The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals (2nd ed.). London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. pp. 174–179. ISBN 978-1472-912-367.

- Skinner, J. D.; Chimimba, C. T. (2006). "Caracal". The Mammals of the Southern African Sub-region (3rd (revised) ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 397–400. ISBN 978-1107-394-056.

- Liebenberg, L. (1990). A Field Guide to the Animal Tracks of Southern Africa. Cape Town, South Africa: D. Philip. pp. 257–258. ISBN 978-0864-861-320.

- Heptner, V. G.; Sludskij, A. A. (1992) [1972]. "Caracal". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 2. Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats)]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 498–524. ISBN 90-04-08876-8.

- Sogbohossou, E.; Aglissi, J. (2017). "Diversity of small carnivores in Pendjari Biosphere Reserve, Benin". Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies. 5 (6): 1429–1433. doi:10.22271/j.ento.

- Aerts, Raf (2019). Forest and woodland vegetation in the highlands of Dogu'a Tembien. In: Nyssen J., Jacob, M., Frankl, A. (Eds.). Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- Wam (2019). "Arabian Caracal sighted in Abu Dhabi for first time in 35 years". Emirates 24/7. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Wam (2019). "Arabian Caracal spotted in Abu Dhabi for first time in 35 years". Emirates News Agency. Abu Dhabi: Khaleej Times. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Gritsina, M. (2019). "The Caracal Caracal caracal Schreber, 1776 (Mammalia: Carnivora: Felidae) in Uzbekistan". Journal of Threatened Taxa. 11 (4): 13470–13477. doi:10.11609/jott.4375.11.4.13470-13477.

- Mukherjee, S.; Goyal, S.P.; Johnsingh, A.J.T. & Pitman, M.L. (2004). "The importance of rodents in the diet of jungle cat (Felis chaus), caracal (Caracal caracal) and golden jackal (Canis aureus) in Sariska Tiger Reserve, Rajasthan, India" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 262 (4): 405–411. doi:10.1017/S0952836903004783.

- Singh, R.; Qureshi, Q.; Sankar, K.; Krausman, P.R. & Goyal, S.P. (2014). "Population and habitat characteristics of caracal in semi-arid landscape, western India". Journal of Arid Environments. 103: 92–95. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2014.01.004.

- Avenant, N.L.; Nel, J.A.J. (1998). "Home-range use, activity, and density of caracal in relation to prey density". African Journal of Ecology. 36 (4): 347–59. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2028.1998.00152.x.

- Stuart, C.T.; Hickman, G. C. (1991). "Prey of caracal (Felis caracal) in two areas of Cape Province, South Africa". Journal of African Zoology. 105 (5): 373–381.

- Palmer, R.; Fairall, N. (1988). "Caracal and African wild cat diet in the Karoo National Park and the implications thereof for hyrax" (PDF). South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 18 (1): 30–34.

- Grobler, J. H. (1981). "Feeding behaviour of the caracal Felis caracal (Schreber 1776) in the Mountain Zebra National Park". South African Journal of Zoology. 16 (4): 259–262. doi:10.1080/02541858.1981.11447764.

- Avenant, N. L.; Nel, J. A. J. (2002). "Among habitat variation in prey availability and use by caracal Felis caracal". Mammalian Biology – Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 67 (1): 18–33. doi:10.1078/1616-5047-00002.

- Bothma, J. D. P. (1965). "Random observations on the food habits of certain Carnivora (Mammalia) in southern Africa". Fauna and Flora. 16: 16–22.

- Kohn, T. A.; Burroughs, R.; Hartman, M. J.; Noakes, T. D. (2011). "Fiber type and metabolic characteristics of lion (Panthera leo), caracal (Caracal caracal) and human skeletal muscle". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 159 (2): 125–133. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.02.006. hdl:2263/19598. PMID 21320626.

- Sunquist, F.; Sunquist, M. (2014). The Wild Cat Book: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know about Cats. Chicago, US: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 87–91. ISBN 978-0226-780-269.

- Bernard, R. T. F.; Stuart, C. T. (1986). "Reproduction of the caracal Felis caracal from the Cape Province of South Africa" (PDF). South African Journal of Zoology. 22 (3): 177–182. doi:10.1080/02541858.1987.11448043.

- Kusminych, I.; Pawlowa, A. (1998). "Ein Bastard von Karakal und Hauskatze im Moskauer Zoo". Der Zoologische Garten. 68 (4): 259–260.

- Abdunazarov, B. B. (2009). "Turkmenskiy karakal Caracal caracal (Schreber, 1776) ssp. michaelis (Heptner, 1945) [Turkmen Caracal Caracal caracal (Schreber, 1776) ssp. michaelis (Heptner, 1945)]". Krasnaya kniga Respubliki Uzbekistan. Chast' II Zhivotnye [The Red Data Book of the Republic of Uzbekistan. Part II, Animals]. Tashkent: Chinor ENK. pp. 192–193.

- Bekenov, A. B.; Kasabekov, B. B. (2010). "Karakal Lynx caracal Schreber, 1776". Krasnaya kniga Respubliki Kazakhstan. Tom 1, Zhivotnye. Chast' 1 Pozvonochnye [The Red Data Book of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Vol. 1, Animals. Part 1, Vertebrates]. Almaty: Ministerstvo obrazovaniya i nauki Respubliki Kazakhstan [Ministry for Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan]. pp. 256–257.

- Mair, V.H. (2006). Contact and exchange in the ancient world. Hawai'i, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. pp. 116–123. ISBN 978-0-8248-2884-4.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Caracal caracal |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Caracal caracal. |

| Look up caracal in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Look up Caracal in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- "Caracal". IUCN Cat Specialist Group.

- Cats For Africa : Caracal Distribution

- "Arabian caracal spotted for first time in Abu Dhabi in 35 years". The National (Abu Dhabi). 2019. Retrieved 23 February 2019.