Vulcan Centaur

Vulcan Centaur is a two-stage-to-orbit heavy-lift launch vehicle under development 2014–2020 by United Launch Alliance (ULA), principally funded through National Security Space Launch (NSSL) competition and launch program, to meet the demands of the United States Air Force and US national security satellite launches.

| |

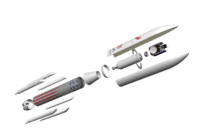

Vulcan configuration as of 2015 with sub-5.4 m Centaur | |

| Function | Launch vehicle, partial reuse planned |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | United Launch Alliance |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Cost per launch | US$~82 - ~200 million (Vulcan Centaur Heavy)[1][2] |

| Size | |

| Height | 61.6 m (202 ft)[3] |

| Diameter | 5.4 m (18 ft)[4] |

| Mass | 546,700 kg (1,205,300 lb) |

| Stages | 2 and 0–6 boosters |

| Capacity | |

| Payload to LEO (28.7°) | 27,200 kg (60,000 lb)[5] (Vulcan Centaur Heavy) |

| Payload to GTO (27°) | 14,400 kg (31,700 lb)[5] (Vulcan Centaur Heavy) |

| Payload to GEO | 7,200 kg (15,900 lb)[5] (Vulcan Centaur Heavy) |

| Payload to TLI | 12,100 kg (26,700 lb)[5] (Vulcan Centaur Heavy) |

| Launch history | |

| Launch sites | |

| First flight | Planned: July 2021[7] |

| Boosters | |

| No. boosters | 0–6[8] |

| Motor | GEM-63XL[9] |

| Thrust | 2,201.7 kN (495,000 lbf) |

| Fuel | HTPB |

| First stage | |

| Diameter | 5.4 m (18 ft) |

| Engines | 2 × BE-4 |

| Thrust | 4,900 kN (1,100,000 lbf) |

| Fuel | CH4/LOX |

| Second stage – Centaur V | |

| Diameter | 5.4 m (18 ft) |

| Engines | 2 × RL-10[10] |

| Thrust | 212 kN (48,000 lbf)[11] |

| Specific impulse | 448.5 seconds (4.398 km/s) |

| Fuel | LH2 / LOX |

| Second stage – ACES (proposed, mid-2020s) | |

| Diameter | 5.4 m (18 ft) |

| Fuel | LH2 / LOX |

The maiden flight is planned to take place in July 2021, launching Astrobotic's Peregrine lunar lander.[12][7]

Vehicle description

Vulcan is ULA's first launch vehicle design, adapting and evolving various technologies previously developed for the Atlas V and Delta IV rockets of the USAF's EELV program. The first stage propellant tanks share the diameter of the Delta IV Common Booster Core, but will contain liquid methane and liquid oxygen propellants instead of the Delta IV's liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen.[13]

Vulcan's upper stage is the Centaur V, an upgraded variant of the Common Centaur/Centaur III currently used on the Atlas V. A lengthened version of the Centaur V will be used on the Vulcan Centaur Heavy.[3] Current plans call for the Centaur V to be eventually upgraded with Integrated Vehicle Fluids technology to become the Advanced Cryogenic Evolved Stage (ACES).[14] Vulcan is intended to undergo the human-rating certification process to allow the launch of crew, such as the Boeing CST-100 Starliner or a future crewed version of the Sierra Nevada Dream Chaser spaceplane.[15]

The Vulcan booster will have a 5.4 m (18 ft) outer diameter to support the methane fuel burned by the Blue Origin BE-4 engines.[16] The BE-4 was selected to power Vulcan's first stage in September 2018 after a competition with the Aerojet Rocketdyne AR1.[17]

Zero to six[8] GEM-63XL[18] solid rocket boosters (SRB)s can be attached to the first stage in pairs,[19] providing additional thrust during the first part of the flight and allowing the six-SRB Vulcan Centaur Heavy to launch a higher mass payload than the most capable Atlas V 551 or Delta IV Heavy.[20]

Vulcan will have a 5.4 m diameter fairing available in two lengths. The longer fairing is 21 m long, with a volume of 317 m3.[8]

Payload mass capabilities

As of November 2019, the Vulcan Centaur payload figures are as follows:[5]

| Version | SRBs | Payload to LEO (kg) | Payload to ISS (kg) | Payload to polar LEO (kg) | Payload to GTO (kg) | Payload to GEO (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vulcan Centaur 502 | 0 | 10,600 | 9,000 | 8,300 | 2,900 | N/A |

| Vulcan Centaur 522 | 2 | 18,500 | 16,100 | 15,000 | 7,600 | 2,600 |

| Vulcan Centaur 542 | 4 | 23,900 | 21,000 | 19,500 | 10,800 | 4,800 |

| Vulcan Centaur 562 | 6 | 27,200 | 25,300 | 23,200 | 13,600 | 6,500 |

| Vulcan Centaur Heavy 5H2 | 6 | 27,200 | 26,200 | 24,000 | 14,400 | 7,200 |

| NSSL requirement[21] | 6,800 | 17,000 | 8,165 | 6,600 |

Payload to LEO is for a 200 km circular orbit at 28.7 degree inclination; payload to ISS is for a 407 km circular orbit at 51.6 degree inclination; payload to polar LEO is for a 200 km circular orbit at 90 degree inclination.[5] These capabilities are driven by the need to meet USAF NSSL requirements, with room for future growth.[21] As can be seen, the direct GEO orbit is the most demanding, with Vulcan Centaur Heavy only 600 kg above the requirement.

History

The United Launch Alliance inherited the Lockheed-Martin Atlas V and the Boeing Delta IV launch vehicle families when the company was formed in 2006. Both were first flown in 2002.

By early 2014 it was clear that ULA would have to develop a new launch vehicle to replace its existing fleet. Additionally, the Atlas V booster uses a Russian RD-180 engine, which led to a push to replace the RD-180 with a U.S. designed and built engine during the Ukrainian crisis of 2014. Relying on foreign hardware to launch critical national security spacecraft was also seen as controversial and undesirable. Formal study contracts were issued by ULA in June 2014 to several U.S. rocket engine suppliers.[22] ULA was also facing competition from SpaceX, then seen to affect ULA's core national security market of U.S. military launches, and by July 2014 the United States Congress was debating whether to legislate a ban on future use of the RD-180.[23]

In September 2014, ULA announced that it had entered into a partnership with Blue Origin to develop the BE-4 liquid oxygen (LOX) and liquid methane (CH4) engine to replace the RD-180 on a new first stage booster. At the time, ULA expected the new booster to start flying no earlier than 2019.[24] ULA had consistently referred to Vulcan as a 'next generation launch system' into early 2015.[24][25]

Announcement

On 13 April 2015, ULA CEO Tory Bruno announced the name—Vulcan—for the new launch vehicle that ULA had been planning for some time. The name was selected by an online poll. Vulcan was intended to incorporate proven technologies. ULA stated its goal was to sell the basic Vulcan for half the then-current US$164 million price of a basic Atlas V rocket. Addition of strap-on boosters for heavier payloads would increase the price.[26] The first launch was initially planned for 2019.[23]

At the time of the 2015 announcement, ULA proposed an incremental approach to rolling out the vehicle and its technologies.[13] Vulcan deployment was expected to begin with a new first stage based on the Delta IV's fuselage diameter and production process and initially expected to use two BE-4 engines, with the AR1 as an alternative. The initial second stage was planned to be the Common Centaur/Centaur III from the Atlas V, with its existing RL10 engine. A later upgrade, the Advanced Cryogenic Evolved Stage (ACES), was conceptually planned for the full development in the late 2010s to be introduced a few years after Vulcan's first flight. ULA also announced a design concept for reuse of the Vulcan booster engines, thrust structure and first stage avionics where they could be detached as a module from the propellant tanks after booster engine cutoff, with the module descending through the atmosphere under an inflatable heat shield.[27] In the event, neither the ACES second stage nor the SMART reuse for the first stage have become funded development projects by ULA as of 2019, even though ULA states that the "first stage propulsion module accounts for around 65% of Vulcan Centaur’s costs."[28]

Funding

Through the first several years, the ULA board of directors made quarterly funding commitments to Vulcan Centaur development.[29] As of October 2018, the US government had committed approximately US$1.2 billion in a public–private partnership to Vulcan Centaur development, with future funding being dependent on ULA securing an NSSL contract.[30]

By March 2016, the US Air Force had committed up to US$202 million of funding for Vulcan development. At that time, ULA had not yet estimated the total cost of Vulcan development, but CEO Tory Bruno noted that "new rockets typically cost $2 billion, including $1 billion for the main engine."[29] In April 2016, ULA Board of Directors member and President of Boeing's Network and Space Systems (N&SS) division Craig Cooning expressed confidence in the possibility of further USAF funding of Vulcan development.[31]

In March 2018, ULA CEO Tory Bruno said that Vulcan-Centaur had been "75 percent privately funded" up to that time.[32] In October 2018 and following a request for proposals and technical evaluation, ULA was awarded $967 million to develop a prototype Vulcan launch system as a part of the National Security Space Launch program. Two other providers, Blue Origin and Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems, were also awarded development funding, with detailed proposals and a competitive selection process to follow in 2019. The USAF's goal with the next generation of Launch Service Agreements is to get out of the business of "buying rockets" and move to acquire launch services from launch service providers, but U.S. government funding of launch vehicle development continues.[30]

Path to production

In September 2015, ULA and Blue Origin announced an agreement to expand the production capabilities of the BE-4 rocket engine then in development and test.[33]

In January 2016, ULA was designing two versions of the Vulcan first stage. The BE-4 version has a 5.4 m diameter to support the use of less-dense methane fuel.[16]

In late 2017, the upper stage was changed to the larger and heavier Centaur V, and the overall launch vehicle was renamed Vulcan Centaur.[32] The single core Vulcan Centaur will be capable of lifting "30% more" than a Delta IV Heavy,[34] meeting the NSSL requirements.[21]

In May 2018, ULA announced the selection of Aerojet Rocketdyne's RL10 engine for the Vulcan Centaur upper stage.[35] In September 2018, ULA announced the selection of the Blue Origin BE-4 engine for Vulcan's booster.[36][37]

In October 2018, the USAF released an NSSL launch service agreement with additional requirements, delaying Vulcan's initial launch to April 2021 after an earlier slip to 2020.[38][39][40]

On 8 July 2019, images of two Vulcan qualification test articles were released by CEO Tory Bruno on Twitter: the liquefied natural gas (fuel) tank[41] and thrust structure.[42] On 9 July 2019, an image of a Vulcan payload attach fitting (PAF) was released by Peter Guggenbach, the CEO of RUAG Space.[43] On 31 July 2019, two images of the mated LNG tank and thrust structure were released by CEO Tory Bruno on Twitter.[44][45]

On 2 August 2019, Blue Origin released on Twitter an image of a BE-4 engine at full power on a test stand.[46] On 6 August 2019, the first two parts of Vulcan's mobile launcher platform (MLP) were transported[47] to the Spaceflight Processing Operations Center (SPOC) near SLC-40 and SLC-41, Cape Canaveral. The MLP was fabricated in eight sections and will move at 3 mph (4.8 km/h) on existing rail dollies and stand 183 feet (56 m) tall.[48]

On 12 August 2019, ULA submitted Vulcan Centaur for phase 2 of the USAF's launch services competition. As of that time, Vulcan Centaur was on track for a 2021 launch.[49] As of February 2020, the tankage for the second operational rocket was under construction in the ULA factory in Decatur, Alabama.[50]

Certification flights

On 14 August 2019, it was announced that the second Vulcan certification flight will be SNC Demo-1, the first of six Dream Chaser CRS-2 flights. Launches are planned to begin in 2021 and will use the four-SRB Vulcan configuration.[51]

On 19 August 2019, it was announced that Astrobotic Technology's Peregrine lander will launch on the first Vulcan certification flight. Peregrine is intended to launch in 2021 from SLC-41 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station.[52]

Potential upgrades

Since the formal announcement in 2015, ULA has spoken of several technologies that would extend the capabilities of the Vulcan launch vehicle. These include enhancements to the first stage——to make the most expensive components potentially reusable, and enhancements to the second stage to increase the long-term mission duration of the stage to operate for weeks or months in Earth orbit cislunar space. By 2020, ULA has not funded nor begun these development efforts.[28]

ACES upper stage with Integrated Vehicle Fluids

A conceptual upgrade to the upper stage of Vulcan at the time of the announcement in 2015 was the ACES upper stage,[13] which was described to be liquid oxygen (LOX) and liquid hydrogen (LH2) powered by one to four rocket engines yet to be selected, a stage that could subsequently be upgraded to include the Integrated Vehicle Fluids (IVF) technology that could allow much longer on-orbit life of the upper stage, measured in weeks rather than hours.[53][13] In the event, neither the ACES upper stage nor the IVF technology capabilities have been added to ULA's planned Vulcan capabilities for the early 2020s.[28]

SMART reuse

Also announced during the initial April 2015 unveiling was the 'Sensible Modular Autonomous Return Technology' (SMART) reuse concept. The booster engines, avionics, and thrust structure would be detached as a module from the propellant tanks after booster engine cutoff, with the module descending through the atmosphere under an inflatable heat shield. After parachute deployment, the module would be captured by a helicopter in mid-air. ULA estimated that this would reduce the cost of the first stage propulsion by 90%, and 65% of the total first stage cost.[27] Through 2020, ULA has not announced firm plans to fund and build/test this engine-reuse concept, though they stated in late 2019 that they were "still planning to eventually reuse Vulcan’s first-stage engines."[28]

Planned launches

| Date/time (UTC) |

Configuration | Launch site | Payloads | Planned destination |

Customer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q2 2021[54][55] | 522 | SLC-41 | Peregrine lander | Selenocentric | Astrobotic Technology |

| First launch | |||||

| September 2021[55][56] | 542 | SLC-41 | SNC Demo-1 | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) |

| Second launch; first with Dream Chaser.[51] | |||||

| 2021 and on[56] | 542 | SLC-41 | Dream Chaser | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) |

| 5 more launches on contract.[56] | |||||

References

- Clark, Stephen. "ULA needs commercial customers to close Vulcan rocket business case". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- Shalal, Klotz, Andrea, Irene. "'Vulcan' rocket launch in 2019 may end U.S. dependence on Russia". Reuters. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- "Vulcan Centaur Cutaway Poster" (PDF). ULA. November 2019. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- Peller, Mark. "United Launch Alliance" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 12, 2016. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- "Rocket Rundown – A Fleet Overview" (PDF). ULA. November 2019. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- Clark, Stephen (October 12, 2015). "ULA selects launch pads for new Vulcan rocket". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved October 12, 2015.

- Wall, Mike. "SpaceX Falcon 9 Rocket Will Launch Private Moon Lander in 2021". Space.com. 2 October 2019. Quote: "But Peregrine will fly on a different rocket, United Launch Alliance's Vulcan Centaur, which is still in development. The 2021 Peregrine mission will be the first for both the lander and its launch vehicle".

- @ToryBruno (July 1, 2019). "Vulcan is configurable with 0 to 6 SRBs. 2 fairing lengths, the longer, 70 ft fairing having a massive 11,000 cuft (317cu-m) payload volume" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Rhian, Jason. "ULA selects Orbital ATK's GEM 63/63XL SRBs for Atlas V and Vulcan Boosters". Spaceflight Insider. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- "United Launch Alliance Selects Aerojet Rocketdyne's RL10 Engine". ULA. May 11, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- "Aerojet Rocketdyne RL10 Propulsion System" (PDF). Aerojet Rocketdyne. March 2019.

- Neal, Mihir (June 8, 2020). "Vulcan on track as ULA eyes early-2021 test flight to the Moon".

- Gruss, Mike (April 13, 2015). "ULA's Vulcan Rocket To be Rolled out in Stages". SpaceNews. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- Bruno, Tory (October 10, 2017). "Building on a successful record in space to meet the challenges ahead". Space News.

- Tory Bruno. ""@A_M_Swallow @ULA_ACES We intend to human rate Vulcan/ACES"". Twitter.com. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

- de Selding, Peter B. (March 16, 2016). "ULA intends to lower its costs, and raise its cool, to compete with SpaceX". SpaceNews. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

Methane rocket has a lower density so we have a 5.4 meter design outside diameter, while drop back to the Atlas V size for the kerosene AR1 version.

- "United Launch Alliance Building Rocket of the Future with Industry-Leading Strategic Partnerships". September 28, 2018.

- Jason Rhian (September 23, 2015). "ULA selects Orbital ATK's GEM 63/63 XL SRBs for Atlas V and Vulcan boosters". Spaceflight Insider.

- @ToryBruno (July 1, 2019). "No. Vulcan SRBs come in pairs" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- "United Launch Alliance Unveils America's New Rocket – Vulcan: Innovative Next Generation Launch System will Provide Country's Most Reliable, Affordable and Accessible Launch Service". ULA. April 13, 2015. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- Space and Missile Systems (October 5, 2018). "EELV LSA RFP OTA". Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved June 22, 2019.

table 10 of page 27

- Ferster, Warren (September 17, 2014). "ULA To Invest in Blue Origin Engine as RD-180 Replacement". Space News. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- Gruss, Mike (April 24, 2015). "Evolution of a Plan : ULA Execs Spell Out Logic Behind Vulcan Design Choices". Space News. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- Fleischauer, Eric (February 7, 2015). "ULA's CEO talks challenges, engine plant plans for Decatur". Decatur Daily. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- Avery, Greg (October 16, 2014). "ULA plans new rocket, restructuring to cut launch costs in half". Denver Business Journal. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- Clark, Stephen (April 22, 2015). "ULA needs commercial business to close Vulcan rocket business case". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- Ray, Justin (April 14, 2015). "ULA chief explains reusability and innovation of new rocket". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- Henry, Caleb (November 20, 2019). "ULA gets vague on Vulcan upgrade timeline". SpaceNews. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Gruss, Mike (March 10, 2016). "ULA's parent companies still support Vulcan … with caution". SpaceNews. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- Erwin, Sandra (October 10, 2018). "Air Force awards launch vehicle development contracts to Blue Origin, Northrop Grumman, ULA". SpaceNews.com. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- Host, Pat (April 12, 2016). "Cooning Confident Air Force Will Invest In Vulcan Development". Defense Daily. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- Erwin, Sandra (March 25, 2018). "Air Force stakes future on privately funded launch vehicles. Will the gamble pay off?". SpaceNews. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- "Boeing, Lockheed Differ on Whether to Sell Rocket Joint Venture". Wall Street Journal. September 10, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- ToryBruno (President & CEO of ULA). "Vulcan Heavy?". Reddit.com. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- Tribou, Richard (May 11, 2018). "ULA chooses Aerojet Rocketdyne over Blue Origin for Vulcan's upper stage engine". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- "United Launch Alliance Building Rocket of the Future with Industry-Leading Strategic Partnerships – ULA Selects Blue Origin Advanced Booster Engine for Vulcan Centaur Rocket System" (Press release). United Launch Alliance. September 27, 2018.

- Johnson, Eric M.; Roulette, Joey (September 27, 2018). "Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin to supply engines for Vulcan rocket". Reuters. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- Foust, Jeff (October 25, 2018). "ULA now planning first launch of Vulcan in 2021". SpaceNews. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- @jeff_foust (January 18, 2018). "Tom Tshudy, ULA: with Vulcan we plan to maintain reliability and on-time performance of our existing rockets, but at a very affordable price. First launch mid-2020" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Foust, Jeff. "ULA now planning first launch of Vulcan in 2021". Space News, October 25, 2018.

- @ToryBruno (July 8, 2019). "I spy a Vulcan booster LNG qualification tank just finished and heading off to structural testing..." (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- @ToryBruno (July 8, 2019). "How do you get over a million pounds of thrust from a pair of BE4 rocket engines efficiently into the rest of the rocket? With a ultra high performance thrust structure. Here's Vulcan's on its way to structural testing" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- @PeterGuggenbach (July 9, 2019). "Flying saucer at Area 51? Nope! Our first out-of-autoclave Payload Attach Fitting (PAF), produced on a 360-degree mold, is headed to the oven in our @RUAGSpace Decatur, Alabama facility. This PAF will be used on the @ULALaunch #VulcanCentaur" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- @ToryBruno (July 31, 2019). "Look at that beautiful bird! This first Vulcan booster is heading off to structural qual testing to verify Vulcan's advanced design and manufacturing tech. Super proud of our Decatur team. #MadeInAlabama. #ULArocketStars @ulalaunch" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- @ToryBruno (July 31, 2019). "Here's another shot of the Vulcan Structural Test qual booster to give you a size comparison. Mighty Atlas on the left. Great Vulcan on the right. A new class of space launch vehicle; the single-core heavy #TheBeast" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- @blueorigin (August 2, 2019). "BE-4 continues to rack up time on the test stand. Here's a great shot of our full power engine test today #GradatimFerociter" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- @ToryBruno (August 6, 2019). "Mighty Atlas is not the only thing rolling at the Cape today. Check the new Vulcan MLP arrival" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- @ULAlaunch (August 6, 2019). "The MLP will transport #VulcanCentaur Vertical Integration Facility to SLC-41 using heritage undercarriage dollies used for Titan III, Titan IV and #AtlasV and will move at 3 mph. #VulcanCentaur" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- "Vulcan Centaur Rocket on Schedule for First Flight in 2021: ULA Submits Proposal for U.S. Air Force's Launch Services Competition". www.ULAlaunch.com. ULA. August 12, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- Sandlin, Destin (February 29, 2020). "How Rockets Are Made (Rocket Factory Tour - United Launch Alliance) - Episode 231". YouTube. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "SNC Selects ULA for Dream Chaser® Spacecraft Launches: NASA Missions to Begin in 2021". ULALaunch. August 14, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- "Astrobotic Selects United Launch Alliance Vulcan Centaur Rocket to Launch its First Mission to the Moon". ULALaunch. August 19, 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- "America, meet Vulcan, your next United Launch Alliance rocket". Denver Post. April 13, 2015. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- "Vulcan on track as ULA eyes early-2021 test flight to the Moon". NASASpaceFlight.com. June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- Pietrobon, Steven (August 27, 2019). "United States Commercial ELV Launch Manifest". Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- "Cargo Dream Chaser solidifies ULA deal by securing six Vulcan Centaur flights". NASASpaceFlight.com. August 14, 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vulcan (rocket). |

- Official ULA Vulcan page

- xTTkrxVR_20 ISPCS 2015 Keynote, Mark Peller, Program Manager of Major Development at ULA and Vulcan Program Manager discusses Vulcan, October 8, 2015. Key discussion of Vulcan is at 12:20 point in video.

- 7a758ea8_0 A current ULA Vulcan with 5.4 m Centaur image

_launches_with_LRO_and_LCROSS_cropped.jpg)