Taiwanese Mandarin

Taiwanese Mandarin, or Guoyu (simplified Chinese: 国语; traditional Chinese: 國語; pinyin: Guóyǔ; lit.: 'National Language'), is a variety of Mandarin Chinese and a national language of Taiwan.[4] The core of its standard form is described in the dictionary Guoyu Cidian (國語辭典) maintained by the Ministry of Education.[5] It is based on the phonology of the Beijing dialect together with the grammar of vernacular Chinese.[6]

| Taiwanese Mandarin | |

|---|---|

| 臺灣華語, Táiwān Huáyǔ 中華民國國語, Zhōnghuá Mínguó Guóyǔ | |

| Pronunciation | Standard Chinese [tʰai˧˥wan˥xwa˧˥ɥy˨˩˦]

Hokkien Influenced [tʰai˧˥wan˥fa˧˥ji˨˩˦] Hakka Influenced [tʰai˧˥wan˥xwa˧˥ji˨˩˦] |

| Native to | Taiwan |

Native speakers | (4.3 million cited 1993)[1] L2 speakers: more than 15 million (no date)[2] |

Sino-Tibetan

| |

| Traditional Chinese characters | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Ministry of Education (Taiwan) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| ISO 639-6 | goyu (Guoyu) |

| Glottolog | taib1240[3] |

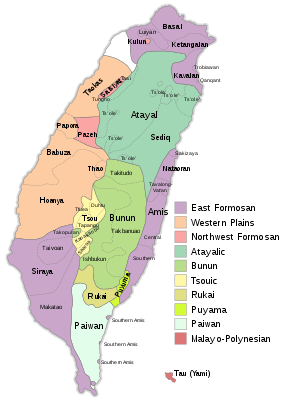

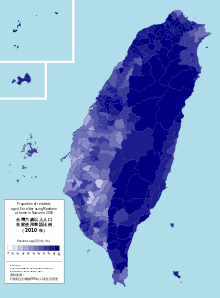

Percentage of Taiwanese aged 6 and above speaking Mandarin at home in 2010 | |

| Taiwanese Mandarin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 臺灣華語 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 台湾华语 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| National language of the Republic of China | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中華民國國語 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中华民国国语 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Standard Taiwanese Mandarin closely resembles and is mutually intelligible with Standard Chinese, the official language of mainland China (simplified Chinese: 普通话; traditional Chinese: 普通話; pinyin: Pǔtōnghuà), with some divergences in pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar. These divergences are the result of a number of factors, including the unique influence of other languages in Taiwan, mainly, Japanese, Taiwanese Hokkien, and to a lesser extent, Taiwanese Hakka. Additionally, the de facto political separation of Taiwan (formally, the Republic of China) and mainland China (the People's Republic of China) after the Chinese Civil War ended in 1949 contributed to many differences in vocabulary, especially for words created after 1949, such as those related to computer science.[7] The PRC adopted simplified Chinese characters beginning in the 1950s, while Taiwan maintained the more complex traditional characters from which simplified characters were derived, resulting in a systematic difference in the written script as well.

History and usage

Large-scale Han Chinese settlement of Taiwan began in the 17th century, with Hoklo immigrants from Fujian province speaking Southern Min (Hokkien), and to a lesser extent, Hakka immigrants speaking their language.[8] Official communications were done in Mandarin (官話 guānhuà, literally: 'Official language'), but the primary languages of everyday life were Hokkien or Hakka, to a lesser extent.[9] After its defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War, the Qing dynasty ceded Taiwan to the Empire of Japan, which governed the island as an Imperial colony from 1895 to 1945. By the end of the colonial period, Japanese had become the high dialect of the island as the result of decades of "Japanization" policy.[9]

After the Republic of China under Kuomintang fled to Taiwan in 1945, Mandarin was introduced as the official language and made compulsory in schools, despite the fact that few native Taiwanese spoke it.[10] The Mandarin Promotion Council (now called National Languages Committee) was established in 1946 by Taiwan Chief Executive Chen Yi to standardize and popularize the usage of Standard Mandarin in Taiwan. The Kuomintang highly discouraged the use of Hokkien and other vernaculars, even portraying them as inferior,[11] and school children could be punished for speaking their home languages.[10] Mandarin was thus established as a lingua franca among the various groups in Taiwan.

Mandarin remains the dominant language in Taiwan, but following the end of martial law in Taiwan in 1987, the country underwent a liberalization of language policy. Local languages were no longer proscribed in public discourse, mass media, or schools.[12] Mandarin is still the main language of public education, with English and "mother tongue education"(Chinese: 母語教育; pinyin: mǔyǔ jiàoyù) being introduced as subjects in primary school.[13] Mother tongue classes generally occupy much less time than Mandarin classes, however, and English classes are often preferred by parents and students over mother tongue classes.[14] Overall, while the government at both national and local levels has promoted the use of non-Mandarin Chinese languages, younger generations generally prefer using Mandarin.[15][16]

Taiwanese Mandarin (as with Singlish and many other situations of a diglossia) is spoken at different levels according to the social class and situation of the speakers. More formal occasions call for the acrolectal level of Guoyu (Standard Mandarin). Less formal situations often result in the basilect form, which has more uniquely Hokkien features. Bilingual speakers often code-switch between Mandarin and Hokkien, sometimes in the same sentence.[17]

Mandarin is spoken fluently by almost the entire Taiwanese population, except for some elderly people who were educated under Japanese rule. In the capital Taipei, where there is a high concentration of Mainlanders whose native variety is not Hokkien, Mandarin is used in greater frequency and fluency than other parts of Taiwan. As of 2010, in addition to Mandarin, Hokkien is natively spoken by around 70% of the population, and Hakka by 15%.[18]

Divisions

Taiwanese Mandarin can be divided into three dialects, Taipei Mandarin (臺北腔; Táiběi qiāng), Taichung Mandarin (臺中腔; Táizhōng qiāng) and Southern Taiwan Mandarin (南臺話; Nántái huà).

Differences from Mainland Mandarin

Script

Taiwanese Mandarin uses traditional Chinese characters like in the two Special administrative regions of China, Hong Kong and Macau, rather than the simplified Chinese characters used in mainland China.

Taiwanese Mandarin users may use informal shorthand suzi (Chinese: 俗字; pinyin: súzì; lit.: 'custom/conventional characters'; also 俗體字 sútǐzì) when writing. Often, suzi are identical to their simplified counterparts, but may also take after Japanese kanji, or differ from both, as shown in the table below. Some suzi are used as frequently as standard characters in printed media, such as the tai in Taiwan being written 台, as opposed to 臺.[19]:251

| Suzi | Standard traditional | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 会[20] | 會 | Identical to simplified 会 (huì) |

| 机[20] | 機 | Identical to simplified 机 (jī) |

| 発 | 發 | Identical to standard kanji, cf. simplified 发 (fā) |

| 奌 | 點 | Form not used in simplified Chinese or Japanese, where it is 点 (diǎn) |

| 庅 | 麼 | Form not used in simplified Chinese (么) or Japanese (麼) (me, má) |

Taiwanese braille is based on different letter assignments than Mainland Chinese braille.

Romanization

Chinese language romanization in Taiwan differs somewhat from in the mainland, where Hanyu Pinyin is used almost exclusively. A competing pinyin system, Tongyong Pinyin, had been formally revealed in 1998 with the support of Taipei mayor Chen Shuibian.[21]:200 In 1999, however, the Legislative Yuan endorsed a slightly modified Hanyu Pinyin, creating paralleled romanization schemes along largely partisan lines, with Kuomintang-supporting areas using Hanyu Pinyin, and Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) using Tongyong Pinyin.[21]:200 In 2002, the Taiwanese government led by the DPP promulgated established Tongyong Pinyin as the country's preferred system, but this was formally abandoned in 2009 in favor of Hanyu Pinyin.[22]

In addition, various other historical romanization systems also coexist across the island, sometimes together in the same locality. Following the defeat of the Kuomintang and subsequent retreat to Taiwan, little emphasis was placed on romanizing Chinese characters, and the default was the Wade-Giles system.[21]:199 The Gwoyeu Romatzyh method, invented in 1928, also was in use during this time period, but to a lesser extent.[21]:199[23]:12 In 1984, Taiwan's Ministry of Education began revising the Gwoyeu Romatzyh method out of concern that Hanyu Pinyin was gaining prominence internationally. Ultimately, a revised version of Gwoyeu Romatzyh was released in 1986,[21]:199 formally called the National Phonetic Symbols, Second Scheme, but this was not widely adopted.[23]:13

Pronunciation

There are two categories of pronunciation differences. The first is of characters that have an official pronunciation that differs from Putonghua, primarily in the form of differences in tone, rather than in vowels or consonants. The second is more general, with differences being unofficial and arising through Taiwanese Hokkien influence on Guoyu.

Variant official pronunciations

There are many notable differences in official pronunciations, mainly in tone but also in initials and finals, between Guoyu and Putonghua. Some differences only apply in certain contexts, while others are universal.

The following is a list of examples of such differences from the Cross-strait language database:[24]

| Taiwanese Mandarin Guoyu (ROC) | Chinese Mandarin

Putonghua |

Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 垃圾 'garbage' | lèsè | lājī | The pronunciation of lèsè originates from Wu Chinese and was the common pronunciation in China before 1949. |

| 步驟 (步骤) 'step, measure' | bùzòu | bùzhòu | |

| 和 'and' | hàn, hé | hé | The hàn pronunciation only applies when 和 is used as a conjunction; in words like 和平 hépíng 'peace' it is not pronounced hàn. |

| 星期 'week' | xīngqí | xīngqī | |

| 企業 (企业) 'enterprise' | qìyè | qǐyè | |

| 成績 (成绩) 'achievement; academic grades' |

chéngjī | chéngjì | |

| 危險 (危险) 'danger; dangerous' | wéixiǎn | wēixiǎn | |

| 微波爐 (微波炉) 'microwave oven' | wéibōlú | wēibōlú | |

| 暴露 'to expose' | pùlù | bàolù | The pronunciation bào is used in all other contexts in Taiwan |

| 攻擊 (攻击)

'attack' |

gōngjí | gōngjī | |

| 質量 (质量)

'mass; quality' |

zhíliàng | zhìliàng | The noun is less commonly used to express 'quality' in Taiwan. 質 is pronounced as zhí in most contexts in Taiwain, except in select words like 'hostage' (人質 rénzhì) or 'to pawn' (質押 zhìyā). |

| 髮型 (发型)

'hairstyle' |

fǎxíng | fàxíng | In Taiwan, 髮 ('hair') is pronounced as fǎ. The simplified form of 髮 is identical to that of the semantically unrelated 發 fā 'to emit, send out'. |

| 口吃

'stutter' |

kǒují | kǒuchī | |

| 暫時 (暂时)

'temporary' |

zhànshí | zànshí |

Hokkien-influenced

Hokkien-influenced Mandarin (known as Taiwan Guoyu 台灣國語 or simply Guoyu) used to be more commonly heard in Central and Southern Taiwan, where the general populace speaks more Taiwanese Hokkien rather than Mandarin. These Hokkien-influenced Mandarin accent in Taiwan is generally similar to the Hokkien-influenced Mandarin accent in Minnan region of Fujian.

In acrolectal Taiwanese Mandarin:

- The retroflex sounds (zh, ch, sh, r) from Putonghua tend to merge with the alveolar series (z, c, s), becoming more retracted version of alveolar consonants like [t͡s̠ʰ][t͡s̠][s̠][z̠].[25]

- Erhua is rarely heard as a diminutive.[25]

- Isochrony is considerably more syllable-timed than in other Mandarin dialects (including Putonghua), which are stress-timed. Consequently, the "neutral tone" (輕聲 qīngshēng) does not occur as often, and the final syllable retains its tone.[25]

- The syllable written as pinyin: eng after b, f, m, p and w is pronounced as [oŋ].[26]

In basilectal Taiwanese Mandarin, sounds that do not occur in Hokkien are replaced by sounds from Hokkien. These variations from Standard Mandarin are similar to the variations of Mandarin spoken in southern China. Using the Hanyu Pinyin system, the following sound changes take place (going from Putonghua to Taiwanese Mandarin followed with an example):

- Complete replacement of retroflex sounds (zh, ch, sh, r) by alveolar consonants (z, c, s, l). r may also become [z]. The ability to produce retroflex sounds is considered a hallmark of "good" Mandarin, and may be overcompensated in some speakers, causing them to pronounce alveolar consonants as their retroflex counterparts when attempting to speak "proper" Mandarin.[27] (e.g. 所以 suǒyǐ → shuǒyǐ)

- f- becomes a voiceless bilabial fricative (⟨ɸ⟩), closer to a light 'h' in standard English (fǎn → huǎn 反 → 緩)[28] (This applies to native Hokkien speakers; Hakka speakers maintain precisely the opposite, e.g. huā → fā 花 → 發)

- endings -uo, -ou, and -e (when it represents a close-mid back unrounded vowel, like in 喝 hē 'to drink') merge into the close-mid back rounded vowel -o

- -ie, ye becomes ei (tie → tei)

- the close front rounded vowel in words such as 雨 yǔ 'rain' become unrounded, transforming into yǐ[29]

- the diphthong ei is monophthongized [e][29]

- the triphthong [uei] (as in 對 duì 'right, correct') similarly becomes [ei] or [e][29]

Grammar

For non-recurring events, the construction involving 有 (yǒu) is used where the sentence final particle 了 (le) would normally be applied to denote perfect. For instance, Taiwanese Mandarin more commonly uses "你有看醫生嗎?" to mean "Have you seen a doctor?" whereas Putonghua uses "你看醫生了嗎?". This is due to the influence of Hokkien grammar, which uses 有 (ū) in a similar fashion. For recurring or certain events, however, both Taiwanese and Mainland Mandarin use the latter, as in "你吃飯了嗎?", meaning "Have you eaten?"

Another example of Hokkien grammar's influence on Taiwanese Mandarin is the use of 會 (huì) as "to be" verbs before adjectives, in addition to the usual meanings "would" or "will". For instance:

- Taiwanese Mandarin: 你會冷嗎? (lit. "you are cold INT?")

- Taiwanese Mandarin: 我會冷 (lit. "I am cold.")

- Taiwanese Mandarin: 我不會冷 (lit. "I not am cold.")

This reflects Hokkien syntax, as shown below:

- Hokkien: 你會寒𣍐? (lit. "you are cold, not?")

- Hokkien: 我會寒 (lit. "I am cold.")

- Hokkien: 我𣍐寒 (lit. "I not cold.")

In Putonghua, sentences would more likely be rendered as follows:

Vocabulary

Vocabulary differences can be divided into several categories – particles, different usage of the same term, loan words, technological words, idioms, and words specific to living in Taiwan. Because of the limited transfer of information between mainland China and Taiwan after the Chinese civil war, many items that were invented after this split have different names in Guoyu and Putonghua. Additionally, many terms were adopted from Japanese both as a result of its close proximity (Okinawa) as well as Taiwan's status as a Japanese territory in the first half of the 20th century.

Particles

Spoken Taiwanese Mandarin uses a number of Taiwan specific (but not exclusive) final particles, such as 囉 (luō), 嘛(ma), 喔 (ō), 耶 (yē), 咧 (lie), 齁 (hō), 咩 (mei), 唷 (yō), etc.

Same words, different meaning

Some terms have different meanings in Taiwan and China, which can sometimes lead to misunderstandings between speakers of different sides of the Taiwan Strait. Often there are alternative, unambiguous terms which can be understood by both sides.

| Term | Meaning in Taiwan | Meaning in China | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 土豆 tǔdòu |

peanut | potato | Unambiguous terms:

| |

| 搞 gǎo |

to carry out something insidious, to have sex (vulgar/slang) | to do, to perform a task | As such, it is a verb that is rarely seen in any official or formal setting in Taiwan, whereas it is widely used in China even by its top officials in official settings.

The word 弄 (nòng) can be used inoffensively in place of 搞 in both Taiwan and China to convey the action "to do; to perform a task" as 弄 is widely used in both places and does not carry the vulgar connotation. While many Mainland speakers are in fact aware of the term's connotations (and it can mean the same thing in China), it is still used normally and is rarely misunderstood. | |

| 窩心 (T) 窝心 (S) wōxīn |

a kind of warm feeling | having an uneased mind | ||

| 出租車 (T) 出租车 (S) chūzūchē |

rental car | taxi | In Taiwan, taxis are called 計程車 / 计程车 (jìchéngchē), which is used less frequently in China. However, many taxis in Taiwan have 個人出租汽車 written on them. Despite the fact that the term chuzuche literally means "car for rent," the term is almost completely unheard of in Taiwan. | |

| 研究所 yánjiūsuǒ (China) yánjiùsuǒ (Taiwan) |

graduate school | research institute | ||

| 愛人 (T) 爱人 (S) àirén |

lover (unmarried)/mistress | spouse | ||

| 小姐 xiǎojie |

Miss | Miss (formal); prostitute (informal, mostly in the North) |

While it is common to address women with unknown marital status as xiǎojie in Taiwan, it can make a negative impression in China's North, although it is still widely used in formal and informal circumstances on the Mainland. The standard definition on the Mainland has a broader range, however, and could be used to describe a young woman regardless of if she is married or not. |

In addition, words with the same literal meaning as in Standard Chinese may differ in register in Taiwanese Mandarin. For instance, éryǐ 而已 'that's all, only' is very common in Taiwanese Mandarin, influenced by speech patterns in Hokkien, but in Standard Chinese the word is used mainly in formal writing, not spoken language.[32]

Different preferred usage

Some terms can be understood by both sides to mean the same thing; however, their preferred usage differs.

| Term | Taiwan | China |

|---|---|---|

| tomato | fānqié (番茄), literally "foreign eggplant" | xīhóngshì (西红柿), literally "western red persimmon" (fānqié is the preferred term in southern China) |

| bicycle | jiǎotàchē (腳踏車), literally "pedaling/foot-stamp vehicle", tiémǎ (鐵馬), literally "metal horse" | zìxíngchē (自行车), literally "self-propelled vehicle" (脚踏车 - jiǎotàchē is the preferred term in Wu-speaking areas) |

| kindergarten | yòuzhìyuán (幼稚園), (loanword from Japanese yōchien 幼稚園) |

yòu'éryuán (幼儿园) |

| pineapple | fènglí (鳳梨) | bōluó (菠萝) |

| dress | liánshēnqún (連身裙), yángzhuāng (洋裝), literally "western clothing" | liányīqún (连衣裙), qúnzi (裙子) |

| hotel | 飯店 (fàndiàn) 'food store' | 酒店 (jĭudiàn) 'alcohol store' |

| Big Mac | Dàmàikè (大麥克) | Jùwúbà (巨无霸) |

| Mandarin | 國語 (guóyŭ) 'national language', 華語(huáyŭ) 'Chinese language', 中文(zhōngwén) 'Chinese language' | 普通话 (pŭtōnghuà) 'common speech' |

This also applies in the use of some function words. Preference for the expression of modality often differs among northern Mandarin speakers and Taiwanese, as evidenced by the selection of modal verbs. Compared to native speakers from Beijing, Taiwanese Mandarin users very strongly prefer 要 yào and 不要 búyào over 得 děi and 別 bié to express 'must' and 'must not', for instance, though both pairs are grammatical in either dialect.[33]

Loan words

Loan words may differ largely between Putonghua and Taiwanese Mandarin, as different characters or methods may be chosen for transliteration (phonetical or semantical), even the number of characters may differ. For example, former U.S. President Barack Obama's surname is called 奥巴馬 Àobāmǎ in Putonghua and 歐巴馬 or 歐巴瑪 Ōubāmǎ in Guoyu.

From English

The term (麻吉 májí) borrowed from the English term "match", is used to describe items or people which complement each other well. Note that this term has become popular in mainland China as well.

The English term "hamburger" has been adopted in many Chinese-speaking communities. In Taiwan, the preferred form is 漢堡 (hànbǎo) rather than the mainland Chinese 漢堡包 (hànbǎobāo) though 漢堡 (hànbǎo) is used as abbreviated form in Mainland as well.

From Taiwanese Hokkien

The terms "阿公 agōng" and "阿媽 amà" are more commonly heard than the standard Mandarin terms 爺爺 yéye (paternal grandfather), 外公 wàigōng (maternal grandfather), 奶奶 nǎinai (paternal grandmother) and 外婆 wàipó (maternal grandmother).

Some local foods usually are referred to using their Hokkien names. These include:

| Hokkien (mixed script) | Pe̍h-ōe-jī (POJ) | IPA | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| 礤冰[34]/chhoah冰[35][36] | chhoah-peng | [tsʰuaʔ˥˧piŋ˥] | baobing: shaved ice with sliced fresh fruit on top (usually strawberry, kiwi or mango) |

| 麻糍[34]/麻糬[35] | môa-chî | [mua˧tɕi˧˥] | glutinous rice cakes (see mochi) |

| 蚵仔煎 | ô-á-chian | [o˧a˥tɕiɛn˥] | oyster omelette |

List of Taiwanese Hokkien words commonly found in local Mandarin-language newspapers and periodicals

| As seen in two popular newspapers[37] | Hokkien (POJ) | Mandarin equivalent (Pinyin) | English | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

鴨霸

|

壓霸

|

惡霸

|

a local tyrant; a bully | ||||||||

肉腳

|

(滷)肉腳

|

無能

|

incompetent; foolish person; a person whose ability is unmatched with those around him. (compare to baka) | ||||||||

ㄍㄧㄥ

|

硬

|

硬

|

(adj, adv) obstinate(ly), tense (as of singing/performing) | ||||||||

甲意

|

佮意[34]/合意

|

喜歡

|

to like | ||||||||

見笑[38]

|

見笑

|

害羞

|

shy; bashful; sense of shame | ||||||||

摃龜

|

摃龜

|

落空

|

to end up with nothing | ||||||||

龜毛[39]

|

龜毛

|

不乾脆

|

picky; high-maintenance | ||||||||

| Q | 𩚨[34]

|

軟潤有彈性

(ruǎn rùn yǒu tánxìng) |

description for food—soft and pliable (like mochi cakes) | ||||||||

LKK

|

老硞硞[34]/老柝柝[35]

|

老態龍鍾

|

old and senile | ||||||||

趴趴走

|

拋拋走

|

東奔西跑

|

to muck around | ||||||||

歹勢

|

歹勢

|

不好意思

|

I beg your pardon; I am sorry; Excuse me. | ||||||||

速配

|

四配

|

相配

|

(adj) well-suited to each other | ||||||||

代誌

|

代誌

|

事情

|

an event; a matter; an affair | ||||||||

凍未條

|

擋袂牢[40]/擋bē-tiâu[35]

|

1受不了

|

1can not bear something

| ||||||||

凍蒜

|

當選

|

當選

|

to win an election[41] | ||||||||

頭殼壞去

|

頭殼歹去

|

腦筋有問題

|

(you have/he has) lost (your/his) mind! | ||||||||

凸槌

|

脫箠

|

出軌

|

to go off the rails; to go wrong | ||||||||

運將

|

un51-chiang11[34]/ùn-chiàng[35]

|

司機

|

driver (of automotive vehicles; from Japanese unchan (運ちゃん), slang for untenshi (運転士), see (運転手)) | ||||||||

鬱卒

|

鬱卒

|

悶悶不樂

|

depressed; sulky; unhappy; moody |

From Japanese

Japanese loanwords based on kanji, now pronounced using Mandarin.

| Japanese (Romaji) | Taiwanese Mandarin (Pinyin) | Mainland Chinese Mandarin (Pinyin) | English | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 弁当 (bentō) | 便當 (biàndāng) | 盒饭 (héfàn) | A boxed lunch. | 弁当 in Japanese was borrowed from a Classical Chinese term using different characters but reintroduced to Taiwan via Mandarin as 便當 via different characters via 便 instead of 弁 because 便 means "convenient" which certainly is what a bento box is. In China, they used the semantic approach. |

| 達人 (tatsujin) | 達人 (dárén) | 高手 (gāoshǒu) | Someone who is very talented at doing something (a pro or expert) or adult. Also written 大人. | 達人 has the same meaning in Classical Chinese, but not widely used in vernacular Chinese in mainland china.[42] |

| 中古 (chūko) | 中古 (zhōnggǔ) | 二手 (èrshǒu) | Used, second-hand. |

Japanese loanwords based on phonetics, transliterated using Chinese characters with similar pronunciation in Mandarin or Taiwanese Hokkien.

| Japanese (Romaji) | Taiwanese Mandarin[43] (Pinyin) | English |

|---|---|---|

| 気持ち (kimochi) | 奇檬子 (qíméngzǐ)[44] | Mood; Feeling. |

| おばさん (obasan) | 歐巴桑 (ōubāsāng)[45] | Old lady; Auntie. |

| おでん (oden) | 黑輪 (hēilún)[46] | A type of stewed flour-based snack/sidedish. |

| おじさん (ojisan) | 歐吉桑 (ōujísāng)[47] | Old man; Uncle. |

| オートバイ (ōtobai) | 歐多拜 (ōuduōbài) | motorcycle ("autobike", from "autobicycle"). |

Technical terms

Taiwanese Mandarin (Pinyin)

|

Mainland Chinese Mandarin (Pinyin)

|

English | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

部落格 (bùluògé)

|

博客 (bókè)

|

Blog | ||||

光碟 (guāngdié)

|

光盘 (guāngpán)

|

Optical disc | ||||

滑鼠 (huáshǔ)

|

鼠标 (shǔbiāo)

|

mouse (computing) | ||||

加護病房 (jiāhùbìngfáng)

|

监护病房 (jiānhùbìngfáng)

|

Intensive Care Unit (ICU); Intensive Treatment Unit (ITU) | ||||

雷射 (léishè)

|

激光 (jīguāng)

|

Laser | ||||

錄影機 (lùyǐngjī)

|

录像机 (lùxiàngjī)

|

videocassette recorder | ||||

軟體 (ruǎntǐ)

|

软件 (ruǎnjiàn)

|

software | ||||

(網際)網路 ([wǎngjì] wǎnglù)

|

互联网 (hùliánwǎng), 網絡 (wǎngluo)

|

Internet | ||||

印表機 (yìnbiǎojī)

|

打印机 (dǎyìnjī)

|

computer printer | ||||

硬碟 (yìngdié)

|

硬盘 (yìngpán)

|

Hard disk | ||||

螢幕 (yíngmù)

|

显示器 (xiǎnshìqì)

|

computer monitor (螢幕 is the equivalent of "screen (noun)" in English, while 显示 means "to display" in English) | ||||

資料庫 (zīliàokù)

|

数据库 (shùjùkù)

|

database | ||||

資訊 (zīxùn)

|

信息 (xìnxī)

|

Information | ||||

作業系統 (zuòyè xìtǒng)

|

操作系统 (cāozuò xìtǒng)

|

operating system |

Idioms and proverbs

Taiwanese Mandarin (Pinyin)

|

Mainland Chinese Mandarin (Pinyin)

|

English | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

一蹴可幾 (yī cù kě jī)

|

一蹴而就 (yī cù ér jiù)

|

to reach a goal in one step | ||||

一覽無遺 (yī lǎn wú yí)

|

一览无余 (yī lǎn wú yú)

|

to take in everything at a glance | ||||

入境隨俗 (rù jìng suí sú)

|

入乡随俗 (rù xiāng suí sú)

|

When in Rome, do as the Romans do. | ||||

揠苗助長

|

拔苗助長

|

Words specific to living in Taiwan

| Mandarin Google hits: .tw Google hits: .cn |

Pinyin | English |

|---|---|---|

| 安親班 .tw: 261,000 .cn: 4,330 |

ānqīnbān | after school childcare (lit. happy parents class) |

| 綁樁 .tw: 78,400 .cn: 992 |

bǎngzhuāng | pork barrel (lit. bind stumps together) |

| 閣揆[48] .tw: 38,200 .cn: 8,620 |

gékuí | the premier (surname + kui for short) |

| 公車 .tw: 761,000 .cn: 827,000[49] |

gōngchē | public bus (in the PRC, 公车 also/mainly refers to government owned vehicles) |

| 機車 .tw: 2,500,000 .cn: 692,000 |

jīchē | motor scooter/(slang) someone or something extremely annoying or irritating (though the slang meaning is often written 機扯)(means "locomotive" in mainland China)[50] |

| 捷運 .tw: 1,320,000 .cn 65,600 |

jiéyùn | rapid transit (e.g. Kaohsiung MRT, Taipei Metro); the term 地铁 (meaning “underground railway”) is used in mainland China, Hong Kong and Singapore but is not applicable to Taiwan due to the relocation of Taiwan Railway Administration lines underground in urban areas since the 1980s and the presence of elevated sections on Taiwanese metro lines such as the Taoyuan Airport MRT. |

| 統一編號[51] .tw: 997,000 .cn: 133,000 |

tǒngyī biānhào | the Government Uniform ID number of a corporation |

Notes

- Mandarin Chinese (Taiwan) at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- Mandarin Chinese (Taiwan) at Ethnologue (14th ed., 2000).

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Taibei Mandarin". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- "LEARNING MANDARIN". Taiwan.gov.tw The official website of the Republic of China. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

In modern Taiwan, traditional Chinese characters are utilized as the written form of Mandarin, one of the nation’s official languages.

- "首頁 > 凡例 > 本辭典編輯首頁 > 凡例 > 本辭典編輯目標" (in Chinese).

本辭典係以正編為基礎,企能編輯成一本簡易且符合實用的工具書,建立今日(五年以內)國語形音義的使用標準,並附上常用易混名物及概念等插圖,以利教學及海內外一般人士研習國語文所需。

- Chen, Ping (1999). Modern Chinese: History and Sociolinguistics. Cambridge University Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780521645720.

- Yao, Qian (September 2014). "Analysis of Computer Terminology Translation Differences between Taiwan and Mainland China". Advanced Materials Research. 1030-1032. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.1030-1032.1650.

- Scott, Mandy; Tiun, Hak-khiam (23 January 2007). "Mandarin-Only to Mandarin-Plus: Taiwan". Language Policy. 6 (1): 53–72. doi:10.1007/s10993-006-9040-5.

- Scott & Tiun 2007, p. 55.

- Scott & Tiun 2007, p. 57.

- Su, Jinzhi (21 January 2014). "Diglossia in China: Past and Present". In Árokay, Judit; Gvozdanović, Jadranka; Miyajima, Darja (eds.). Divided languages?: Diglossia, Translation and The Rise of Modernity in Japan, China, and the Slavic World. pp. 61–2. ISBN 978-3-319-03521-5.

- Scott & Tiun 2007, p. 58.

- Scott & Tiun 2007, p. 60.

- Scott & Tiun 2007, p. 64.

- Scott & Tiun 2007, pp. 59-60.

- Yap, Ko-hua (December 2017). "臺灣民眾的家庭語言選擇" [Family Language Choice in Taiwan] (PDF). 臺灣社會學刊 [Taiwanese Journal of Sociology] (in cn) (62): 59–111. Retrieved 24 May 2020.CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

- Chiu, Miao-chin (April 2012). "Code-switching and Identity Constructions in Taiwan TV Commercials" (PDF). Monumenta Taiwanica. 5. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "2010 population and household census in Taiwan" (PDF). Government of Taiwan (in Chinese). Taiwan Ministry of Education. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- Wang, Boli; Shi, Xiaodong; Chen, Yidong; Ren, Wenyao; Yan, Siyao (March 2015). "语料库语言学视角下的台湾汉字简化研究" [On the Simplification of Chinese Characters in Taiwan: A Perspective of Corpus Linguistics]. Acta Scientiarum Naturalium Universitatis Pekinensis (in Chinese). 51 (2). doi:10.13209/j.0479-8023.2015.043.

- Su, Dailun (12 April 2006). "基測作文 俗體字不扣分 [Basic Competence Test will not penalize nonstandard characters]". Apple Daily (in Chinese). Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Lin, Peiyin (December 2015). "Language, Culture, and Identity: Romanization in Taiwan and Its Implications". Taiwan Journal of East Asian Studies. 12 (2). doi:10.6163/tjeas.2015.12(2)191.

- Shih, Hsiu-chuan (18 September 2008). "Hanyu Pinyin to be standard system in 2009". Taipei Times. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Chiung, Wi-vun Taiffalo. "Romanization and Language Planning in Taiwan*" (PDF). The Linguistic Association of Korea Journal. 9 (1). Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "中華語知識庫 (Chinese Language Database)". The General Association of Chinese Culture. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Chen (1999), p. 47.

- Chen (1999), p. 48.

- Kubler (1985), p. 159.

- Kubler (1985), p. 157.

- Kubler (1985), p. 160.

- Lu (2011).

- Sanders, Robert M. (1992). "THE EXPRESSION OF MODALITY IN PEKING AND TAIPEI MANDARIN / 關於北京話和台北國語中的情態表示". Journal of Chinese Linguistics. 20 (2): 289–314. ISSN 0091-3723. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Kubler (1985), p. 171.

- Sanders 1992, p. 289.

- MoE (2011).

- Iûⁿ.

- Often written using the Mandarin equivalent 刨冰, but pronounced using the Taiwanese Hokkien word.

- Google hits from the China Times (中時電子報) and Liberty Times (自由時報) are included.

- This can be a tricky one, because 見笑 means "to be laughed at" in Standard Mandarin. Context will tell you which meaning should be inferred.

- Many people in Taiwan will use the Mandarin pronunciation (guīmáo).

- MoE (2011), 擋 entry.

- the writing 凍蒜 (lit. freeze garlic) probably originated in 1997, when the price of garlic was overly raised, and people called for the government to gain control of the price.

- 晋 葛洪 《抱朴子·行品》:“顺通塞而一情,任性命而不滞者,达人也。” 贾谊 《鵩鸟赋》:“小智自私兮,贱彼贵我;达人大观兮,物无不可。”

- 臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典-外來詞 [Dictionary of Frequently-Used Taiwan Minnan - Loanwords] (in Chinese). Ministry of Education (Republic of China). 2011. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- Derived from Taiwanese 起毛-chih (Pe̍h-ōe-jī: khí-mo͘-chih; [ki˧mɔ˥ʑi˧]; see 起毛)

- Most people in Taiwan will use the Taiwanese pronunciation (Pe̍h-ōe-jī: o·-bá-sáng; [ɔ˧ba˥saŋ˥˧])

- Derived from Hokkien 烏輪 (Pe̍h-ōe-jī: o͘-lián; [ɔ˧liɛn˥˧])

- Most people in Taiwan will use the Taiwanese pronunciation (Pe̍h-ōe-jī: o·-jí-sáng; [ɔ˧ʑi˥saŋ˥˧])

- The first character 閣 is usually omitted when placed behind the surname. For example, the former premier was Su Tseng-chang (蘇貞昌). Since his surname is 蘇, he was referred to in the press as 蘇揆.

- The numbers are a bit misleading in this case because in the PRC, 公车 also refers to government owned vehicles.

- Young people in Taiwan also use this word to refer to someone or something extremely annoying or irritating.

- Often abbreviated as 統編 (tǒngbiān).

References

- Chen, Ping (1999). Modern Chinese: History and sociolinguistics. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64572-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chen, Shou (2000). Tâi-ôan-ōe tōa-sû-tián 台灣話大詞典 [A Dictionary of Taiwanese] (in Chinese). Taipei: Yuan-Liou. ISBN 9789573240785.

- Iûⁿ, Ún-giân. "Tâi-bûn/Hôa-bûn Sòaⁿ-téng Sû-tián" 台文/華文線頂辭典 [On-line Taiwanese/Mandarin Dictionary] (in Chinese and English).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kubler, Cornelius C. (1985). "The Influence of Southern Min on the Mandarin of Taiwan". Anthropological Linguistics. 27 (2): 156–176. ISSN 0003-5483. JSTOR 30028064.

- Kuo, Yun-Hsuan (2005). New dialect formation: The case of Taiwanese Mandarin (Ph.D.). Colchester: Department of Language and Linguistics, University of Essex. OCLC 61123947.

- Lu, Huang Cheng (2011). Tâi-gí sû-tián 簡明台語詞典 [A Dictionary of Taiwanese] (in Chinese). Taipei: 文水藝文事業有限公司. ISBN 9789868696648.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- 臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典 [Dictionary of Frequently-Used Taiwan Minnan] (in Chinese). Ministry of Education (Republic of China). 2011. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- Tseng, Hsin-I (2003). 當代台灣國語的句法結構 [The syntax structures of contemporary Taiwanese Mandarin] (M.A. Thesis) (in Chinese). Taipei: National Taiwan Normal University. OCLC 185021205.