Chinese postal romanization

Postal romanization[1] was a system of transliterating Chinese place names developed by postal authorities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For many cities, the postal romanization was the most common English-language form of the city's name from the 1890s until the 1980s, when the pinyin system was adopted.

| Chinese postal romanization | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

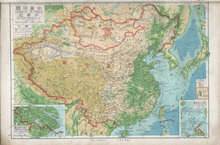

A map of China with romanizations published in 1947 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 郵政式拼音 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 邮政式拼音 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Postal-style romanization system | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

In the late 19th century, China had various competing postal services, including a British postal service and the Imperial Maritime Customs Post Office. After postmarking equipment was introduced in the 1880s, postage was cancelled with a stamp that gave the city of origin in Latin letters. In 1896, the Customs Post was combined with other postal services and renamed the Chinese Imperial Post. With the post office a national agency, the romanizations it used could be treated as standard.

When the Wade-Giles system of romanization became widespread, some argued that the post office should adopt it. This idea was rejected at a conference held in 1906 in Shanghai. The conference selected a system developed by Herbert Giles called "Nanking syllabary".[2] This decision allowed the post office to continue using various romanizations that it had already selected. Wade-Giles romanization is based on the Beijing dialect, which is now standard. The system the post office adopted is based on Nanjing pronunciation. The Nanjing dialect had been China's lingua franca until it was displaced by the Beijing dialect in the mid-19th century.

Table of romanizations

| Chinese | D'Anville (1790)[3] | China Inland Mission (1898)[4] | Postal[5] | Wade-Giles[6] | Pinyin[7] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peking | Peking | Peking (1919) | Pei-ching | Běijīng | |

| [Name for Beijing used in 1928-1949] | Peiping (1947) | Pei-p'ing | Běipíng | ||

| Tching-tou-fou | Chentu | Chengtu | Ch’eng-tu | Chéngdū | |

| Tchong-kin-fou | Chungking | Chungking | Ch'ung-ch'ing | Chóngqìng | |

| Quang-tong | Kuangtung | Kwangtung | Kuang-tung | Guăngdōng | |

| Quang-tcheou or Canton | Canton | Canton (1919) Kwangchow (1947) | Kuang-chou | Guăngzhōu | |

| Quei-li-ng-fou | Kweilin | Kweilin | Kuei-lin | Guìlín | |

| Hang-tcheou | Hangchau | Hangchow | Hang-chou | Hángzhōu | |

| Kiang-nan | Kiang-su | Kiangsu | Chiang-su | Jiāngsū | |

| Tci-nan-fou | Tsinan | Tsinan | Chi-nan | Jĭnán | |

| Nan-king | Nanking | Nanking | Nan-ching | Nánjīng | |

| [Qingdao was founded in 1899] | Tsingtao | Ch’ing-tao | Qīngdǎo | ||

| Se-tchuen | Si-chuen | Szechwan | Ssu-ch'uan | Sìchuān | |

| Sou-tcheou-fou | Suchau | Soochow | Su-chou | Sūzhōu | |

| Tien-king-oei | Tientsin | Tientsin | T’ien-chin | Tiānjīn | |

| Hia-men or Emoui | Amoy | Amoy | Hsia-men | Xiàmén | |

| Si-ngan-fou | Sian | Sianfu (1919) Sian (1947) | Hsi-an | Xī'ān | |

The spelling "Amoy" is based on pronunciation in Hokkien, the local language. The other postal romanizations are based on "Southern Mandarin," an idealized form of Nanjing dialect. The irregular "oo" in "Soochow" is to distinguish this city from Xuzhou (Suchow) in northern Jiangsu. Pinyin spellings are based on putonghua, an idealization of Beijing dialect taught in the Chinese education system.

After the Chinese Nationalist Party came to power in 1927, the capital was moved from Beijing ("northern capital") to Nanjing ("southern capital"). Beijing was renamed "Peiping" ("northern peace"). In addition, the non-systematic spelling "Canton" was dropped, at least officially.[8]

History

In 1866, the Imperial Maritime Customs Service, led by Irishman Robert Hart, created the Customs Post to handle the correspondence between the government in Beijing and the legations in Tianjin and Shanghai.[9] In 1878, this service was opened to the public and expanded. Postage stamps were issued at this time. By 1882, the Customs Post had offices in twelve Treaty Ports: Shanghai, Amoy, Chefoo, Chinkiang, Chungking, Foochow, Hankow, Ichang, Kewkiang, Nanking, Weihaiwei, and Wuhu. Local offices had postmarking equipment so that all mail was marked with a romanized form of the city's name. In additional, there were companies that provided local postal service in each of these cities. From January 1893 to September 1896, these companies issued their own postage stamps that featured the romanized names.

An imperial edict issued in 1896 designated the Customs Post a national postal service and renamed it the Chinese Imperial Post. The local post offices in the Treaty Ports were incorporated into the new service. The Customs Post was smaller than other postal services in China, such as the British. As the Imperial Post, it grew rapidly and soon became the dominant player in the market.

In 1899, Hart, as inspector general of posts, asked postmasters to submit romanizations for their districts. Although Hart asked for transliterations "according to the local pronunciation", most postmasters were reluctant to play lexicographer and simply looked up the relevant characters in a dictionary. The spellings that they submitted generally followed a system created by Thomas Francis Wade, now called the Wade–Giles system. The system had been developed in 1867 and was based on the Beijing pronunciation. It became the standard method of romanizing Chinese after Herbert Giles published a dictionary, using the system, in 1892.[10]

| Chinese romanization |

|---|

| Mandarin |

|

Sichuanese |

| Wu |

| Yue |

| Southern Min |

| Eastern Min |

| Northern Min |

| Pu-Xian Min |

| Hainanese |

| Gan |

|

Chang-Du dialect |

| Hakka |

| Xiang |

|

Chang–Yi dialects |

| See also |

|

Other transliterations |

The post office published a draft romanization map in 1903.[11] Disappointed with the Wade-based map, Hart issued another directive in 1905. This one told postmasters to submit romanizations "not as directed by Wade, but according to accepted or usual local spellings." Local missionaries could be consulted, Hart suggested. However, Wade's system did reflect pronunciation in Mandarin-speaking areas.[lower-alpha 1]

Théophile Piry, a long-time customs manager, was appointed postal secretary in 1901. Appointing a French national to the top position fulfilled an 1898 commitment by China to "take into account the recommendations of the French government" when selecting staff for the post office. Until 1911, the post office remained part of the Maritime Customs Service, which meant that Hart was Piry's boss.[12]

1906 conference

To resolve the romanization issue, Piry organised an Imperial Postal Joint-Session Conference[13] in Shanghai in the spring of 1906. This was a joint postal and telegraphic conference. The conference resolved that existing spellings would be retained for names already transliterated. Accents, apostrophes, and hyphens would be dropped to facilitate telegraphic transmission. The requirement for addresses to be given in Chinese characters was dropped. For new transliterations, local pronunciation would be followed in Guangdong as well as in parts of Guangxi and Fujian. In other areas, a system called Nanking syllabary would be used.[8]

Nanking syllabary was a transliteration system presented by Giles in his Dictionary.[lower-alpha 2] Nanjing dialect had been China's lingua franca until the mid-19th century, when it was replaced by Beijing dialect. Nanking syllabary was described as a romanization of "Southern Mandarin." This is an idealized form of the Jianghuai dialect spoken in the lower Yangtze region. Jianghuai is a divergent form of Mandarin and is widely spoken in both Jiangsu and Anhui provinces. In Giles' idealization, the speaker consistently makes various phonetic distinctions not made in Beijing dialect (or in the dialect of any other specific city). Giles created the system to encompass a range of dialects. It also supports the traditional romanizations "Peking" and "Nanking," which go back to the D'Anville map of 1737. The selection of Nanking syllabary did not suggest that the post office was treating Nanjing pronunciation as standard. The principal advantage of the system was that it allowed "the romanization of non-English speaking people to be met as far as possible," as Piry put it.[2]

Atlases explaining postal romanization were issued in 1907, 1919, 1933, and 1936. The ambiguous result of the 1906 conference led critics to complain that postal romanization was idiosyncratic.[8] According to modern scholar Lane J. Harris:

What they have criticized is actually the very strength of postal romanization. That is, postal romanization accommodated local dialects and regional pronunciations by recognizing local identity and language as vital to a true representation of the varieties of Chinese orthoepy as evinced by the Post Office's repeated desire to transcribe according to "local pronunciation" or "provincial sound-equivalents".[14]

Later developments

Prompted by a 1919 Ministry of Education decision to teach the Beijing dialect in elementary schools nationwide, the post office briefly reverted to Wade's system in 1920 and 1921. It was the era of the May Fourth Movement, when language reform was the rage and the Beijing dialect was promoted as a national standard. The post office adopted a dictionary by William Edward Soothill as a reference.[15] The Soothill-Wade system was used for newly created offices. Existing post office retained their romanizations.

In December 1921, Codirector Henri Picard-Destelan quietly ordered a return to Nanking syllabary "until such time as uniformity is possible." Although the Soothill-Wade period was brief, it was a time when 13,000 offices were created, a rapid and unprecedented expansion. At the time the policy was reversed, one third of all postal establishments used Soothill-Wade spelling.[16]

In 1943, the Japanese ousted A. M. Chapelain, the last French head of the Chinese post. The post office had been under French administration almost continuously since Piry's appointment as postal secretary in 1901.[lower-alpha 3]

In 1958, Communist China announced that it was adopting the pinyin romanization system. Implementing the new system was a gradual process. The government did not get around to abolishing postal romanization until 1964.[16] Even then, the post office did not adopt pinyin, but merely withdrew Latin characters from official use, such as in postal cancellation markings.

Mapmakers of the time followed various approaches. Private atlas makers generally used postal romanization in the 1940s, but they later shifted to Wade-Giles.[17] The U.S. Central Intelligence Agency used a mix of postal romanization and Wade-Giles.[18] The U.S. Army Map Service used Wade-Giles exclusively.[19]

The U.S. government and the American press adopted pinyin in 1979.[20][21] The International Organization for Standardization followed suit in 1982.[22]

Postal romanization remained official in Taiwan until 2002, when Tongyong Pinyin was adopted. In 2009, Hanyu Pinyin replaced Tongyong Pinyin as the official romanization (see Chinese language romanization in Taiwan). While street names in Taipei have been romanized via Hanyu Pinyin, municipalities throughout Taiwan, such as Kaohsiung and Taichung, presently use a number of romanizations, including Tongyong Pinyin and postal romanization.

See also

Notes

- This map shows where the various dialects of Chinese are spoken. Both Wade-Giles and pinyin are based on Northern Mandarin, which is shown in red. Although this is often called the "Beijing dialect," both systems leave out language features that are local to Beijing.

- That refers to the first edition of Giles' dictionary, published in 1892.

- The only break in French control of the post office was 1928 to 1931, when Norwegian Erik Tollefsen was foreign head.

References

Citations

- Postal Romanization. Taipei: Directorate General of Posts. 1961. OCLC 81619222.

- Harris (2009), p. 101.

- Anville, Jean Baptiste Bourguignon, Atlas général de la Chine, de la Tartarie chinoise, et du Tibet : pour servir aux différentes descriptions et histoires de cet empire (1790). This is an expanded edition of an atlas first published in 1737.

- "Map of China : prepared for the China Inland Mission," London : Stanford's Geographical Establishment, 1898.

- Jacot-Guillarmod, Charles, Postal Atlas of China, Peking : Directorate General of Posts, 1919.

"Chinese Republic, Outer Mongolia," 1947. p. 6. This map uses postal romanization consistently, but with some misspellings. - "Mongolia and China", Pergamon World Atlas, Pergamon Press, Ltd, 1967).

- "China.," United States. Central Intelligence Agency, 1969.

- Harris, Lane J. (2009). "A "Lasting Boon to All": A Note on the Postal Romanization of Place Names, 1896–1949". Twentieth-Century China. 34 (1): 96–109. doi:10.1353/tcc.0.0007.

- Hart, Robert, The I.G. in Peking: Letters of Robert Hart, Chinese Maritime Customs 1868-1907, Vol. 1, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1975, p. 253.

- Giles, Herbert (1892). A Chinese-English Dictionary. London: Bernard Quaritch.

- China Postal Working Map (1903).

- Twitchett, Denis, and Fairbank, John K., Cambridge History of China: Republican China 1912-1949, Volume 12, part 1, 1983, p. 189.

- 帝國郵電聯席會議 (dìguó yóudiàn liánxí huìyì)

- Harris (2009), p. 97.

- William Edward Soothill (1908). The student's four thousand tzu and general pocket dictionary

- Harris (2009), p. 105.

- Compare Hammond 1948 ("Japan and China," Hammond, C.S. 1948) to Pergamon 1967 ("Mongolia and China", Pergamon World Atlas, Pergamon Press, Ltd, 1967). The latter is a pure Wade-Giles map.

- "China, administrative divisions," United States. Central Intelligence Agency, 1969.

- "China 1:250,000," 1954, Series L500, U.S. Army Map Service.

- Gazetteer of the People's Republic of China, United States. Defense Mapping Agency, United States Board on Geographic Names, 1979. This book lists 22,000 pinyin place names, with Wade-Giles equivalents, that were approved by the BGN for use by agencies of the U.S. government.

- "Times due to revise its Chinese spelling," New York Times, Feb. 4, 1979.

- "ISO 7098:1982 – Documentation – Romanization of Chinese". Retrieved 2009-03-01.

Bibliography

- China Postal Album: Showing the Postal Establishments and Postal Routes in Each Province. 1st ed. Shanghai: Directorate General of Posts, 1907.

- China Postal Album: Showing the Postal Establishments and Postal Routes in Each Province. 2nd ed. Peking: Directorate General of Posts, 1919.

- China Postal Atlas: Showing the Postal Establishments and Postal Routes in Each Province. 3rd ed. Nanking: Directorate General of Posts, 1933.

- China Postal Atlas: Showing the Postal Establishments and Postal Routes in Each Province. 4th ed. Nanking: Directorate General of Posts, 1936.

- Playfair, G. M. H. The Cities and Towns of China: A Geographical Dictionary. 2nd. ed. Shanghai: Kelly & Walsh Ltd., 1910.

- "Yóuzhèng shì pīnyīn" (邮政式拼音) Zhōngguó dà bǎikē quánshū: Yuyán wénzì (中国大百科全书:语言文字). Beijing: Zhōngguó dà bǎikē quánshū chūbǎnshè (中国大百科全书出版社), 1998.