Languages of Taiwan

The languages of Taiwan consist of several varieties of languages under families of Austronesian languages and Sino-Tibetan languages spoken in Taiwan. The Formosan languages, a branch of Austronesian languages, have been spoken by the Taiwanese aborigines in Taiwan for thousands of years. Researches on historical linguistics recognize Taiwan as the Urheimat (homeland) of the whole Austronesian languages family owing to the highest internal variety of the Formosan languages. In the last 400 years, several waves of Chinese emigrations brought several different Sino-Tibetan languages into Taiwan. These languages include Taiwanese Hokkien, Hakka, and Mandarin. These became the major languages of today's Taiwan, and make Taiwan an important center of Hokkien pop and Mandopop.

| Languages of Taiwan | |

|---|---|

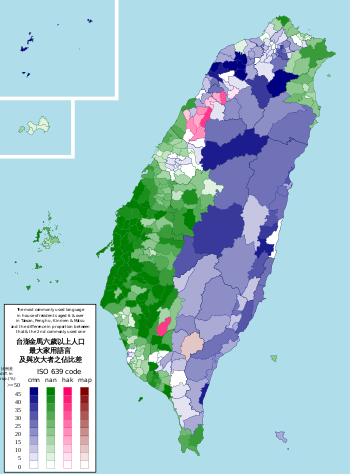

The most commonly used home language in Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu, 2010. (blue 'cmn' = "Mandarin", green 'nan' = "Hokkien"/"Min Nan", hot-pink 'hak' = "Hakka", burgundy 'map' = Austronesian languages) | |

| National | |

| Indigenous | Formosan languages (Amis, Atayal, Bunun, Kanakanabu, Kavalan, Paiwan, Puyuma, Rukai, Saaroa, Saisiyat, Sakizaya, Seediq, Thao, Truku, Tsou), Yami |

| Immigrant | Indonesian, Tagalog, Thai, Vietnamese |

| Foreign | English, Indonesian, Japanese, Tagalog, Thai, Vietnamese[3][4] |

| Signed | Taiwanese Sign Language |

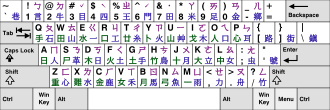

| Keyboard layout | |

Formosan languages were the dominant language of the Prehistory of Taiwan. The long colonial and immigration history of Taiwan brought in several languages such as Dutch, Spanish, Hokkien, Hakka, Japanese and Mandarin. Due to its colonial history, Japanese is also spoken and a large amount of loanwords from Japanese exist in several languages of Taiwan.

After World War II, a long martial law era was held in Taiwan. Policies of the government in this era suppressed languages other than Mandarin in public use. This has significantly damaged the evolution of local languages including Taiwanese Hokkien, Hakka, Formosan languages and Matsu dialect. The situation has slightly changed after the 2000s. The government has put some efforts to protect and revitalize local languages. Local languages are now a part of elementary school education in Taiwan. Laws and regulations regarding local language protection were established for Hakka and Formosan languages. Public TV and radio stations exclusively for the two languages were also established. Currently, the government of Taiwan also maintains standards of several widely spoken languages listed below, the percentage of users are from the 2010 population and household census in Taiwan.[5]

Overview of national languages

| Language | Percentage of home use | Recognised variants | National language | Statutory language for public transport | Regulated by | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandarin | 83.5% | 1 | By legal definition | Required nationwide | Ministry of Education | |

| Taiwanese Hokkien | 81.9% | 1~6 | By legal definition | Required nationwide | Ministry of Education | |

| Hakka | 6.6% | 6 | By designation | Required nationwide | Hakka Affairs Council | |

| Formosan languages | 1.4% | 16 (42) | By designation | Discretionary | Council of Indigenous Peoples | |

| Matsu | <1% | 1 | By legal definition | Required in Matsu Islands | Department of Education, Lienchiang County Government | |

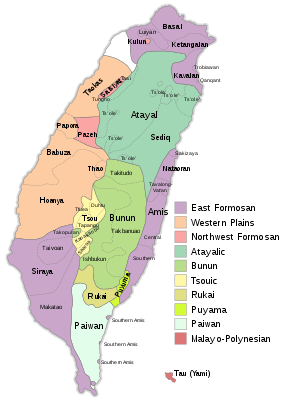

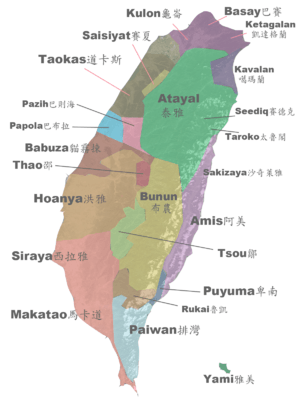

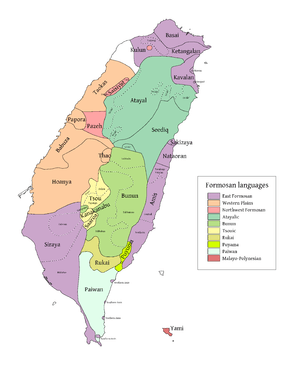

Indigenous languages

The Taiwanese indigenous languages or Formosan languages are the languages of the aboriginal tribes of Taiwan. Taiwanese aborigines currently comprise about 2.3% of the island's population.[7] However, far fewer can still speak their ancestral language, after centuries of language shift. It is common for young and middle-aged Hakka and aboriginal people to speak Mandarin and Hokkien better than, or to the exclusion of, their ethnic languages. Of the approximately 26 languages of the Taiwanese aborigines, at least ten are extinct, another five are moribund,[8] and several others are to some degree endangered. Currently the government recognized 16 languages and 42 accents of the indigenous languages, they are

| Classification | Recognized languages (accents) | |

|---|---|---|

| Formosan | Atayalic | Atayal (6), Seediq (3), Kankei (1) |

| Rukaic | Rukai (6) | |

| Northern Formosan | Saisiyat (1), Thao (1) | |

| Eastern Formosan | Kavalan (1), Sakizaya (1), Amis (5) | |

| Southern Formosan | Bunun (5), Puyuma (4), Paiwan (4) | |

| Tsouic | Tsou (1), Kanakanabu (1), Saaroa (1) | |

| Malayo-Polynesian | Philippine | Yami (1) |

The governmental agency — Council of Indigenous Peoples — maintains the orthography of the writing systems of Formosan languages. Due to the era of Taiwan under Japanese rule, a large number of loanwords from Japanese also appear in Formosan languages. There is also Yilan Creole Japanese as a mixture of Japanese and Atayal.

All Formosan languages are slowly being replaced by the culturally dominant Mandarin. In recent decades the government started an aboriginal reappreciation program that included the reintroduction of Formosan mother tongue education in Taiwanese schools. However, the results of this initiative have been disappointing.[9][10] Television station — Taiwan Indigenous Television, and radio station — Alian 96.3 were created as an efforts to revive the indigenous languages. Formosan languages were made an official language in July 2017.[11][12]

The Amis language is the most widely spoken aboriginal language, on the eastern coast of the island where Hokkien and Hakka are less present than on the western coast. The government estimates put the number of Amis people at a little over 200,000, but number of people who speak Amis as their first language as lower than 10,000.[13] Amis has appeared in some mainstream popular music.[14] Other significant indigenous languages includes Atayal, Paiwan, and Bunun. In addition to the recognized languages, there are around 10 to 12 groups of Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples with their respective languages.

Some indigenous people and languages are recognized by local governments, these include Siraya (and its Makatao and Taivoan varieties) to the south-west of the island. Some other language revitalization movements are going on Basay to the north, Babuza-Taokas in the most populated western plains, and Pazeh bordering it in the center west of the island.

Sinitic languages

Taiwanese Mandarin

Mandarin is commonly known and officially referred to as the national language (國語; Guóyǔ) in Taiwan. In 1945, following the end of World War II, Mandarin was introduced as the official language and made compulsory in schools. (Before 1945, Japanese was the official language and taught in schools.) Since then, Mandarin has been established as a lingua franca among the various groups in Taiwan: the majority Hokkien-speaking Hoklo, the Hakka who have their own spoken language, the aboriginals who speak Austronesian languages; as well as Mainland Chinese who immigrated in 1949 whose native tongue may be any Chinese variant.

People who emigrated from mainland China after 1949 (12% of the population) mostly speak Mandarin Chinese.[15] Mandarin is almost universally spoken and understood.[16] It was the only officially sanctioned medium of instruction in schools in Taiwan from late 1940s to late 1970s, following the handover of Taiwan to the government of the Republic of China in 1945, until English became a high school subject in the 1980s and local languages became a school subject in the 2000s.

Taiwanese Mandarin (as with Singlish and many other situations of a creole speech community) is spoken at different levels according to the social class and situation of the speakers. Formal occasions call for the acrolectal level of Standard Chinese of Taiwan (國語; Guóyǔ), which differs little from the Standard Chinese of China (普通话; Pǔtōnghuà). Less formal situations may result in the basilect form, which has more uniquely Taiwanese features. Bilingual Taiwanese speakers may code-switch between Mandarin and a Taiwanese variety, sometimes in the same sentence.

Many Taiwanese, particularly the younger generations, speak Mandarin better than Hakka or Hokkien, and it has become a lingua franca for the island amongst the Chinese dialects.[17]

Taiwanese Hokkien

Properly known as Holo (河洛語/河洛話), misleadingly called Taiwanese (臺語, Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tâi-gí) and officially referred as Taiwanese Hokkien (臺灣閩南語; Tâi-oân Bân-lâm-gú); Taiwanese Hokkien is the most-spoken native language in Taiwan, spoken by about 70% of the population.[18][19] Linguistically, it is a subgroup of Southern Min languages variety originating in southern Fujian province and is spoken by many overseas Chinese throughout Southeast Asia.

There are both colloquial and literary registers of Taiwanese. Colloquial Taiwanese has roots in Old Chinese. Literary Taiwanese, which was originally developed in the 10th century in Fujian and based on Middle Chinese, was used at one time for formal writing, but is now largely extinct. Due to the era of Taiwan under Japanese rule, a large amount of loanwords from Japanese also appear in Taiwanese. The loanwords may be read in Kanji through Taiwanese pronunciation or simply use the Japanese pronunciation. These reasons makes the modern writing Taiwanese in a mixed script of traditional Chinese characters and Latin-based systems such as pe̍h-ōe-jī or the Taiwanese romanization system derived from pe̍h-ōe-jī in official use since 2006.

Recent work by scholars such as Ekki Lu, Sakai Toru, and Lí Khîn-hoāⁿ (also known as Tavokan Khîn-hoāⁿ or Chin-An Li), based on former research by scholars such as Ông Io̍k-tek, has gone so far as to associate part of the basic vocabulary of the colloquial language with the Austronesian and Tai language families; however, such claims are not without controversy. Recently there has been a growing use of Taiwanese Hokkien in the broadcast media.

Accent differences among Taiwanese dialects are relatively small but still exist. The standard accent — Thong-hêng accent (通行腔) is sampled from Kaohsiung city,[20] while other accents fall into a spectrum between

- Hái-kháu accent (海口腔): representing the accent spoken in Lukang, close to Quanzhou dialect in China, and

- Lāi-po͘ accent (內埔腔): representing the accent spoken in Yilan, close to Zhangzhou dialect in China.

A great part of Taiwanese Hokkien is generally understood by other dialects of Hokkien as spoken in China and South-east Asia (such as Singaporean Hokkien), but also has a degree of intelligibility with the Teochew variant of Southern Min spoken in Eastern Guangdong, China. It is, however, mutually unintelligible with Mandarin or other Chinese languages.

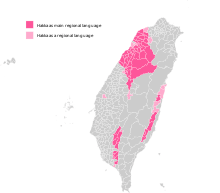

Taiwanese Hakka

Hakka (客家語; Hak-kâ-ngî) is mainly spoken in Taiwan by people who have Hakka ancestry. These people are concentrated in several places throughout Taiwan. The majority of Hakka Taiwanese reside in Taoyuan, Hsinchu and Miaoli. Varieties of Taiwanese Hakka were officially recognized as national languages.[21] Currently the Hakka language in Taiwan is maintained by the Hakka Affairs Council. This governmental agency also runs Hakka TV and Hakka Radio stations. The government currently recognizes and maintains five Hakka dialects (six, if Sixian and South Sixian are counted independently) in Taiwan.[22]

| Subdialect (in Hakka) | Si-yen | Hói-liu̍k | South Si-yen | Thai-pû | Ngiàu-Phìn | Cheu-ôn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subdialect (in Chinese) | 四縣腔 Sixian | 海陸腔 Hailu | 南四縣腔 South Sixian | 大埔腔 Dabu | 饒平腔 Raoping | 詔安腔 Zhao'an |

| Percentage (as of 2013) | 56.1% | 41.5% | 4.8% | 4.2% | 1.6% | 1.3% |

| Percentage (as of 2016) | 58.4% | 44.8% | 7.3% | 4.1% | 2.6% | 1.7% |

Matsu dialect

Matsu dialect (馬祖話, Mā-cū-huâ) is the language spoken in Matsu islands. It is a dialect of Fuzhou dialect, Eastern Min.

Written and sign languages

Chinese characters

Traditional Chinese characters is widely used in Taiwan to write Sinitic languages including Mandarin, Taiwanese Hokkien and Hakka. The Ministry of Education maintains standards of writing for these languages, publications including the Standard Form of National Characters and the recommended characters for Taiwanese Hokkien and Hakka.

Written vernacular Chinese is the standard of written Chinese used in official documents, general literature and most aspects of everyday life, and has grammar based on Modern Standard Mandarin. Vernacular Chinese is the modern written variant of Chinese that supplanted the use of classical Chinese in literature following the New Culture Movement of the early 20th Century, which is based on the grammar of Chinese spoken in ancient times. In recent times, following the Taiwan localization movement and an increasing presence of Taiwanese literature, written Hokkien based on the vocabulary and grammar of Taiwanese Hokkien is occasionally used in literature and informal communications.

Traditional Chinese characters are also used in Hong Kong and Macau. A small number of characters are written differently in Taiwan; the Standard Form of National Characters is the orthography standard used in Taiwan and administered by the Ministry of Education, and has minor variations compared with the standardized character forms used in Hong Kong and Macau. Such differences relate to orthodox and vulgar variants of Chinese characters.

Latin alphabet and Romanization

Latin alphabet is native to Formosan languages and partially native to Taiwanese Hokkien and Hakka. With the early influences of European missionaries, writing systems such as Sinckan Manuscripts, Pe̍h-ōe-jī, and Pha̍k-fa-sṳ were based on in Latin alphabet. Currently the official Writing systems of Formosan languages are solely based on Latin and maintained by the Council of Indigenous Peoples. The Ministry of Education also maintains Latin based systems Taiwanese Romanization System for Taiwanese Hokkien, and Taiwanese Hakka Romanization System for Hakka. The textbooks of Taiwanese Hokkien and Hakka are written in a mixed script of Traditional Chinese characters and Latin alphabet.

Chinese language romanization in Taiwan tends to be highly inconsistent. Taiwan still uses the Zhuyin system and does not commonly use the Latin alphabet as the language phonetic symbols. Traditionally Wade–Giles is used. The central government adopted Tongyong Pinyin as the official romanization in 2002 but local governments are permitted to override the standard as some have adopted Hanyu Pinyin and retained old romanizations that are commonly used. However, in August 2008 the central government announced that Hanyu Pinyin will be the only system of Romanization of Standard Mandarin in Taiwan as of January 2009.

Phonetic symbols

Zhuyin Fuhao, often abbreviated as Zhuyin, or known as Bopomofo after its first four letters, is the phonetic system of Taiwan for teaching the pronunciation of Chinese characters, especially in Mandarin. Mandarin uses 37 symbols to represent its sounds: 21 consonants and 16 rimes. Taiwanese Hokkien uses 45 symbols to represent its sounds: 21 consonants and 24 rimes. There is also a system created for Hakka language.

These phonetic symbols sometimes appear as ruby characters printed next to the Chinese characters in young children's books, and in editions of classical texts (which frequently use characters that appear at very low frequency rates in newspapers and other such daily fare). In advertisements, these phonetic symbols are sometimes used to write certain particles (e.g., ㄉ instead of 的); other than this, one seldom sees these symbols used in mass media adult publications except as a pronunciation guide (or index system) in dictionary entries. Bopomofo symbols are also mapped to the ordinary Roman character keyboard (1 = bo, q = po, a = mo, and so forth) used in one method for inputting Chinese text when using a computer. In more recent years, with the advent of smartphones, it has become increasingly common to see Zhuyin used in written slang terms, instead of typing full characters - for example ㄅㄅ replacing 拜拜 (bye bye). It is also used to give phrases a different tone, like using ㄘ for 吃 (to eat) to indicate a childlike tone in the writing.

The sole purpose for Zhuyin in elementary education is to teach standard Mandarin pronunciation to children. Grade one textbooks of all subjects (including Mandarin) are entirely in zhuyin. After that year, Chinese character texts are given in annotated form. Around grade four, presence of Zhuyin annotation is greatly reduced, remaining only in the new character section. School children learn the symbols so that they can decode pronunciations given in a Chinese dictionary, and also so that they can find how to write words for which they know only the sounds. Even among adults, it is almost universally used in Taiwan to explain pronunciation of a certain character being referred to others.

Sign language

Taiwan has a national sign language, the Taiwanese Sign Language, which was developed from Japanese Sign Language during Japanese colonial rule. TSL has some mutual intelligibility with Japanese Sign Language and the Korean Sign Language as a result. TSL has about a 60% lexical similarity with JSL.[24]

Other languages

Japanese

The Japanese language was compulsorily taught while Taiwan was under Japanese rule (1895 to 1945). Although fluency is now largely limited to the elderly, most of Taiwan's youth who look to Japan as the trend-setter of the region's youth pop culture now might know a bit of Japanese through the media, their grandparents, or classes taken from private "cram schools".

South-East Asian languages

A significant number of immigrants and spouses in Taiwan are from South-East Asia.

- Indonesian: Indonesian is the most widely spoken language among the approximately 140,000 Indonesians in Taiwan.

- Javanese: Javanese is also spoken by Javanese people from Indonesia who are in Taiwan.

- Tagalog: Tagalog is also widely spoken by Filipinos by the approximately 108,520 Filipinos in Taiwan.

- Vietnamese: There are somewhere around 200,000 Vietnamese in Taiwan, many of whom speak Vietnamese. There has been some effort, particularly beginning in 2011, to teach Vietnamese as a heritage language to children of Vietnamese immigrants.[25]

European languages

- Dutch: Dutch was taught to the residents of the island during the Dutch colonial rule of Taiwan. After the withdrawal of Dutch presence in Taiwan, the use of the language disappeared.

- English: English is a common foreign language, with some large private schools providing English instruction.

- Spanish: Spanish was mainly spoken by the northern part of the island during the establishment of a Spanish colony in Formosa until 1642.

Sino-Tibetan languages

- Cantonese: Cantonese is spoken by many recent and early immigrants from Guangdong, Guangxi, Hong Kong, and Macau. Various Cantonese-speaking communities exist throughout Taiwan, and the use of the language in Taiwan continues to increase. There are a reported 87,719 Hongkongers residing in Taiwan as of the early 2010's [26], however it is likely that this number has increased significantly since.

See also

- Taiwanese Aborigines

- Han Taiwanese — Hoklo Taiwanese, Hakka Taiwanese

- Formosan languages

- Taiwanese Hokkien

- Taiwanese Hakka

- Taiwanese Mandarin

References

- Not designated but meets legal definition

Citations

- "Indigenous Languages Development Act". law.moj.gov.tw. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- "Hakka Basic Act". law.moj.gov.tw. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- Taiwanese Talent Turns to Southeast Asia. Language Magazine. Retrieved 2016-01-24.

- Learning Vietnamese gaining popularity in Taiwan. Channel News Asia. Retrieved 2016-01-24.

- "99 年人口及住宅普查 - 總報告統計結果提要分析" (PDF) (in Chinese). Ministry of Education (Republic of China). 2010.

- "臺灣原住民平埔族群百年分類史系列地圖 (A history of the classification of Plains Taiwanese tribes over the past century)". blog.xuite.net. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- Council of Indigenous Peoples, Executive Yuan "Statistics of Indigenous Population in Taiwan and Fukien Areas" Archived 2006-08-30 at the Wayback Machine.

- Zeitoun, Elizabeth & Ching-Hua Yu "The Formosan Language Archive: Linguistic Analysis and Language Processing". Computational Linguistics and Chinese Language Processing. Volume 10, No. 2, June 2005, pp. 167-200

- Lee, Hui-chi (2004). A Survey of Language Ability, Language Use and Language Attitudes of Young Aborigines in Taiwan. In Hoffmann, Charlotte & Jehannes Ytsma (Eds.) Trilingualism in Family, School, and Community Archived 2007-05-26 at the Wayback Machine pp.101-117. Clevedon, Buffalo: Multilingual Matters. ISBN 1-85359-693-0

- Huteson, Greg. (2003). Sociolinguistic survey report for the Tona and Maga dialects of the Rukai Language. SIL Electronic Survey Reports 2003-012, Dallas, TX: SIL International.

- "President lauds efforts in transitional justice for indigenous people". Focus Taiwan. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- Zeldin, Wendy (June 21, 2017). "Taiwan: New Indigenous Languages Act | Global Legal Monitor". Library of Congress. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- "Saving the Amis language one megabyte at a time". Taipei Times. Retrieved 2018-12-05.

- Chang, Chiung-Wen. ""Return to Innocence": In Search of Ethnic Identity in the Music of the Amis of Taiwan". symposium.music.org. College Music Symposium. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- Liao, Silvie (2008). "A Perceptual Dialect Study of Taiwan Mandarin: Language Attitudes in the Era of Political Battle" (PDF). Proceedings of the 20th North American Conference on Chinese Linguistics (NACCL-20). Columbus, Ohio: The Ohio State University. 1: 393. ISBN 9780982471500. OCLC 895153060. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-24.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Chapter 2: People and Language". The Republic of China Yearbook 2012. Executive Yuan, R.O.C. (Taiwan). 2012. p. 24. ISBN 9789860345902. Archived from the original on 2013-10-14. Retrieved 2013-12-18.

- Noble (2005), p. 16.

- Cheng, Robert L. (1994). "Chapter 13: Language Unification in Taiwan: Present and Future". In Rubinstein, Murray (ed.). The Other Taiwan: 1945 to the Present. M.E. Sharpe. p. 362. ISBN 9781563241932.

- Klöter, Henning (2004). "Language Policy in the KMT and DPP eras". China Perspectives. 56. ISSN 1996-4617.

- "臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典編輯凡例". twblg.dict.edu.tw (in Chinese). Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- "Hakka Basic Act". Laws & Regulations Database of The Republic of China. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- "Chapter 2: People and Language" (PDF). The Republic of China Yearbook 2010. Government Information Office, Republic of China (Taiwan). 2010. p. 42. ISBN 9789860252781. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-05.

- 客家委員會 (2017). 105年度全國客家人口暨語言基礎資料調查研究.

- Fischer, Susan et al. (2010). "Variation in East Asian Sign Language Structures" in Sign Languages, p. 501 at Google Books

- Yeh, Yu-Ching; Ho, Hsiang-Ju; Chen, Ming-Chung (2015). "Learning Vietnamese as a heritage language in Taiwan". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 36 (3): 255–265. doi:10.1080/01434632.2014.912284.

- "臺灣地區居留外僑統計". 統計資料. 內政部入出國及移民署. December 31, 2011. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

Sources

- Noble, Gregory W. (2005). "What Can Taiwan (and the United States) Expect from Japan?". Journal of East Asian Studies. 5 (1): 1–34. doi:10.1017/s159824080000624x. JSTOR 23417886.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weingartner, F. F. (1996). Survey of Taiwan aboriginal languages. Taipei. ISBN 957-9185-40-9.

External links

- Mair, V. H. (2003). "How to Forget Your Mother Tongue and Remember Your National Language".CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)