Post-capitalism

Post-capitalism is a state in which the economic systems of the world can no longer be described as forms of capitalism. Various individuals and political ideologies have speculated on what would define such a world. According to some classical Marxist and some social evolutionary theories, post-capitalist societies may come about as a result of spontaneous evolution as capitalism becomes obsolete. Others propose models to intentionally replace capitalism. The most notable among them are socialism and anarchism.

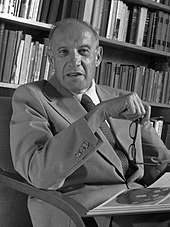

In 1993, Peter Drucker outlined a possible evolution of capitalistic society in his book Post-Capitalist Society.[1] The book stated that knowledge, rather than capital, land, or labor, is the new basis of wealth. The classes of a fully post-capitalist society are expected to be divided into knowledge workers or service workers, in contrast to the capitalists and proletarians of a capitalist society. In the book, Drucker estimated the transformation to post-capitalism would be completed in 2010–2020.

Drucker also argued for rethinking the concept of intellectual property by creating a universal licensing system.[2] Consumers would subscribe for a cost and producers would assume that everything is reproduced and freely distributed through social networks.

In 2015, according to Paul Mason the rise of income inequality, repeating cycles of boom and bust and capitalism’s contributions to climate change has led economists, political thinkers and philosophers to begin to seriously consider how a post-capitalistic society would look and function. Post-capitalism is expected to be made possible with further advances in automation and information technology – both of which are effectively causing production costs to trend towards zero.[3]

Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams identify a crisis in capitalism's ability and willingness to employ all members of society, arguing that "there is a growing population of people that are situated outside formal, waged work, making do with minimal welfare benefits, informal subsistence work, or by illegal means"[4]

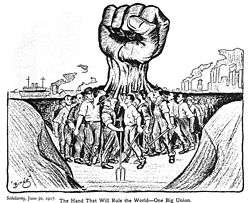

Anarchism

- Anarchist communism, a hybrid of communism and anarchism advocating (among other things) decision making by direct and/or consensus democracy, abolition of the state and abolition of private ownership of the means of production.

- Post-scarcity anarchism, an economic system based on social ecology, libertarian municipalism and an abundance of fundamental resources.

- Anarcho-syndicalism, an ideology centred on self-management of labour, socialism and direct democracy.

Heritage check system

Heritage check system, a socioeconomic plan that retains a market economy, but removes fractional reserve lending power from banks and limits government printing of money to offset deflation with money printed being used to buy materials to back the currency, pay for government programs in lieu of taxes, with the remainder to be split evenly among all citizens to stimulate the economy (termed a "heritage check" for which the system is named). As presented by the original author of the idea, Robert Heinlein, in his book For Us, The Living: A Comedy of Customs, the system would be self-reinforcing and eventually result in a regular heritage checks able to provide a modest living for most citizens.[5]

Economic democracy

- Economic democracy, a socioeconomic philosophy that establishes democratic control of firms by their workers and social control of investment by a network of public banks.[6]

Participatory economy

In his book Of the People, By the People: The Case for a Participatory Economy, Robin Hahnel describes a post-capitalist economy called the participatory economy.[7] The book ends with the proposal of the Green New Deal, a package of policies that address climate change and financial crises.

The participatory economy focuses on the participation of all citizens through the creation of worker councils and consumer councils. Hahnel emphasizes the direct participation of worker and consumers rather than appointing representatives. The councils are concerned with large-scale issues of production and consumption and are broken into various bodies tasked with researching future development projects.

In a participatory economy, economic rewards would be offered according to need, the amount of which would be determined democratically by the workers council. Hahnel also calls for "economic justice" by rewarding people for their effort and diligence rather than accomplishments or prior ownership. A worker’s effort is to be determined by their co-workers. Consumption rights are then rewarded according to the effort ratings. The worker has the choice to decide what they consume using their consumption rights. Hahnel does not address the idea of money, currency, or how consumption rights would be tracked.

Planning in a participatory economy is done through the councils. The process is horizontal across the committees as opposed to vertical. All council members, the workers and consumers, participate directly in planning unlike in Soviet-type economies and other democratic planning proposals in which planning is done by representatives. Planning is an iterative procedure, always being changed and improved upon, that is accomplished at the level of either work or consumption. All information and proposals are freely available to everyone, those inside and outside of the council, so that the social cost of each proposal can be determined and voted on. Long-term plans such as structuring public transportation, residential zones and recreational areas, are to be proposed by delegates and approved by direct democracy (i.e. voting by the population).

Hahnel argues that a participatory economy will return empathy to our purchasing choices. Capitalism removes the knowledge of how and by whom a product was made: "When we eat a salad the market systematically deletes information about the migrant workers who picked it".[8] By removing the human element from goods, consumers only consider their own satisfaction and need when consuming products. Introducing worker and consumer councils would reintroduce the knowledge of where, how and by whom products were manufactured. A participatory economy is expected to also introduce more socially oriented goods, such as parks, clean air, and public health care, through the interaction of the two councils.

For those that call the participatory economy utopian, Albert and Hahnel counter:[8]

Are we being utopian? It is utopian to expect more from a system than it can possibly deliver. To expect equality and justice—or even rationality—from capitalism is utopian. To expect social solidarity from markets, or self-management from central planning, is equally utopian. To argue that competition can yield empathy or that authoritarianism can promote initiative or that keeping most people from decision making can employ human potential most fully: these are utopian fantasies without question. But to recognize human potentials and to seek to embody their development into a set of economic institutions and then to expect those institutions to encourage desirable outcomes is no more than reasonable theorizing. What is utopian is not planting new seeds but expecting flowers from dying weeds.

Socialism

Socialism often implies common ownership of companies and a planned economy, though as an inherently pluralistic ideology, it is argued whether either are essential features.[9] In his book PostCapitalism: A Guide to our Future, Paul Mason argues that centralized planning, even with the advanced technology of today, is unachievable.[3] Rejecting central planning as both technically unachievable and undesirable, Michael Albert and Robin Hahnel argue that democratic planning provides a viable basis for creating a participatory economy.

Helpful definitions surrounding socialism:

- Socialism, an economic system based on public or cooperative ownership of the means of production where production is carried out to directly produce use-value, that includes a moneyless form of accounting such as physical resource accounting or labor-time and based on the direct production of utility rather than on the capitalist laws of accumulation and value. Some models of socialism imply economic planning for the allocation of the factors of production in place of capital markets, while other models of socialism retain market-based allocation of capital goods. Some Marxists believe socialism would eventually in turn evolve into communism.

- Planned socialism, a type of socialism where some form of economic planning substitutes markets for allocating the factors of production and for coordinating the economy. There are various types of planning, including central planning and decentralized planning; material balance planning, input-output planning and computerized planning.

- Market socialism, a type of socialism based on socialization and public or cooperative ownership of the means of production, but retains monetary calculation and market competition and utilizes markets as the primary way of allocating the factors of production.

- Communalism, a political theory based on the writings of Murray Bookchin. Bookchin developed Communalism after he broke with anarchism believing it to be individualist and lifestylist. It is based on libertarian municipalism, confederalism and social ecology. This school of thought has also given rise to democratic confederalism.

In UK politics, strands of Corbynism and the Labour party have adopted this ‘postcapitalist’ tendency.[10][11]

Technology as a driver of post-capitalism

Much of the speculation surrounding the proposed fate of the capitalist system stems from predictions about the future integration of technology into economics. The evolution and increasing sophistication of both automation and information technology is said to threaten jobs and highlight internal contradictions in Capitalism which will allegedly ultimately lead to its collapse.

Automation

Technological change which has driven unemployment has historically been as a result of ‘mechanical-muscle’ machines which have reduced the need for human labour. Just as horses were once employed but were gradually made obsolete by the invention of the automobile, humans' jobs have also been affected throughout history. A modern example of this technological unemployment is the replacement of retail cashiers by self-service checkouts. The invention and development of ‘mechanical-mind’ processes or “brain labour” is thought to threaten jobs at an unprecedented scale, with Oxford Professors Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne estimating that 47 percent of US jobs are at risk of automation.[12] If this leads to a world where human labour is no longer needed then our current market system models, which rely on scarcity, may have to adapt or fail. It is argued that this has been a factor in the creation of many of what David Graeber calls 'bullshit jobs', where, in large bureaucracies, production of anything is not the goal, but exist solely for reasons such as providing sociological benefit to the manager employing them.

Information technology

Postcapitalism is said to be possible due to major changes information technology has brought about in recent years. It has blurred the edges between work and free time [13] and loosened the relationship between work and wages. Significantly, information is corroding the market’s ability to form prices correctly. Information is abundant and information goods are freely replicable. Goods such as music, software or databases do have a production cost, but once made can be copied/pasted infinitely. If the normal price mechanism of capitalism prevails, then the price of any good which has essentially no cost of reproduction will fall towards zero.[14] This lack of scarcity is a problem for our models, which try to counter by developing monopolies in the form of giant tech companies to keep information scarce and commercial. But many significant commodities in the digital economy are now free and open-source, such as Linux, Firefox, and Wikipedia.[15]

See also

- Anti-capitalism

- Commons-based peer production

- Critique of capitalism

- Distributism

- Economic history of the world

- Eco-communalism

- Evolutionary economics

- P2P economic system

- Post-democracy

- Post-scarcity economy

- Resource-based economy

- Sharing economy

- Socialist calculation debate

- Social evolution

- Technological unemployment § Solutions

- The Venus Project

- The Zeitgeist Movement

- Historical materialism

References

- Drucker, Peter F. (1993). Post-Capitalist Society. HarperInformation. ISBN 978-0-7506-0921-0.

- Schwartz, Peter (1 March 1993). "Post-Capitalist". WIRED. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- Mason, Paul (2015). PostCapitalism: A Guide to our Future. Allen Lane. ISBN 9781846147388.

- Srnicek, Nick; Williams, Alex. Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work. Verso Books. pp. 103–104. ISBN 9781784780968

- Heinlein, Robert (2003). For Us, The Living. Scribner. pp. 233. ISBN 978-0-7432-5998-9.

- Schweickart, David (2002). After Capitalism. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0-7425-1299-3.

- Hahnel, Robert (2012). Of the People, By the People: The Case for a Participatory Economy. AK Press Distribution. ISBN 978-0983059769.

- Albert, Michael; Hahnel, Robin. "Participatory Planning" (PDF). Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- Wright, Tony (1986) Socialisms: theories and practices. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192191885.

- Pitts, F. and Dinerstein, A. (2017). Corbynism’s conveyor belt of ideas: Postcapitalism and the politics of social reproduction. Capital & Class, 41(3), pp.423-434.

- Peck, Tom (2016-08-30). "Jeremy Corbyn promises to 'rebuild Britain' with digital manifesto". Independent. Independent. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- Frey, Carl Benedikt; Osborne, Michael A (2017-01-01). "The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation?". Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 114: 254–280. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.395.416. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2016.08.019. ISSN 0040-1625.

- N. Korody. "Architecture after capitalism, in a world without work". Retrieved 25 Jun 2017.

- P. Mason (2015-07-17). "Three dynamics leading to post-capitalism". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 Jun 2017.

- Mason, Paul (17 July 2015). "The end of capitalism has begun". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

Further reading

- Albert, Michael. Parecon: Life After Capitalism. London: Verso, 2003.

- Ankerl, Guy C. Beyond Monopoly Capitalism and Monopoly Socialism: Distributive Justice in a Competitive Society. Cambridge MA: Schenkman, 1978.

- The Associative Economy: Insights beyond the Welfare System and into Post-Capitalism.

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2006). A Postcapitalist Politics. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0816648047

- Mason, Paul (2015). PostCapitalism: A Guide to our Future, London: Allen Lane. ISBN 9781846147388.

- Rifkin, Jeremy (2014). The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Internet of Things, the Collaborative Commons, and the Eclipse of Capitalism. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1137278463

- Shutt, Harry (2010). Beyond the Profits System: Possibilities for the Post-Capitalist Era. Zed Books. ISBN 978-1848134171.

- Srnicek, Nick and Alex Williams. Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work. London: Verso, 2015. ISBN 1784780960.

- Steele, Ramsay Steele (1999). From Marx to Mises: Post-Capitalist Society and the Challenge of Economic Calculation. Open Court. ISBN 978-0875484495.

- Wright, Erik O. Envisioning Real Utopias. London: Verso, 2010.

.jpg)

_(cropped).jpg)