Shining Path

The Communist Party of Peru – Shining Path (Spanish: Partido Comunista del Perú – Sendero Luminoso), more commonly known as the Shining Path (Spanish: Sendero Luminoso), is a revolutionary communist party and political organization in Peru espousing Marxism–Leninism–Maoism and Marxism–Leninism–Maoism–Gonzalo Thought.

Communist Party of Peru Partido Comunista del Perú | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | PCP |

| Leader | Abimael Guzmán |

| Founded | Late 1960s |

| Armed wing | People's Guerrilla Army |

| Ideology | Communism Marxism–Leninism–Maoism Anti-revisionism Gonzalo Thought |

| Political position | Far-left |

| International affiliation | Revolutionary Internationalist Movement |

| Colours | Red |

| Slogan | ¡Viva la Guerra Popular! ¡Guerra Popular hasta el comunismo! "Long live the People's War! People's War until Communism!" |

| Party flag | |

| |

When it first launched during the internal conflict in Peru in 1980, its goal was to overthrow the state by guerrilla warfare and replace it with a New Democracy. The Communist Party of Peru believed that by establishing a dictatorship of the proletariat, inducing a cultural revolution, and eventually sparking a world revolution, they could arrive at full communism. Their representatives stated that the then-existing socialist countries were revisionist, and the Shining Path was the vanguard of the world communist movement. The Communist Party of Peru's ideology and tactics have influenced other Maoist insurgent groups such as the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre) and other Revolutionary Internationalist Movement-affiliated organizations.[1] The Peruvian guerrillas were peculiar in that they had a high proportion of women. 50 per cent of the combatants and 40 per cent of the commanders were women.[2]

The Shining Path has been widely condemned for its brutality,[3][4] including violence deployed against peasants, trade union organizers, elected officials and the general public.[5] The Shining Path is regarded as a terrorist organization by Peru, Japan, the United States, the European Union, and Canada, which consequently prohibit funding and other financial support for the group.[6][7][8][9] Since the capture of its leader Abimael Guzmán in 1992, the Shining Path has declined in activity.[10]

Name

The common name of this group, the Shining Path, distinguishes it from several other Peruvian communist parties with similar names (see Communism in Peru). The name is derived from a maxim of José Carlos Mariátegui, the founder of the original Peruvian Communist Party in the 1920s: "El Marxismo-Leninismo abrirá el sendero luminoso hacia la revolución" ("Marxism–Leninism will open the shining path to revolution").[3]

This maxim was featured on the masthead of the newspaper of a Shining Path front group. Due to the number of Peruvian groups that refer to themselves as the Communist Party of Peru, groups are often distinguished by the names of their publications. The followers of this group are generally called senderistas. All documents, periodicals, and other materials produced by the organization are signed by the Communist Party of Peru (PCP). Academics often refer to them as PCP-SL.

Origins

The Shining Path was founded in 1969 by Abimael Guzmán, a former university philosophy professor (his followers referred to him by his nom de guerre Presidente Gonzalo), and a group of 11 others.[11] His teachings created the foundation of its militant Maoist doctrine. It was an offshoot of the Communist Party of Peru — Bandera Roja (red flag), which in turn split from the original Peruvian Communist Party, a derivation of the Peruvian Socialist Party founded by José Carlos Mariátegui in 1928.[12]

Antonio Díaz Martínez was an agronomist who became a leader of the Sendero Luminoso. His books, Ayacucho, Hambre y Esperanza (1969) and China, La Revolución Agraria (1978) expressed his own conviction of the necessity that revolutionary activity in Peru follow strictly the teachings of Mao Zedong. This was his important contribution to the ideology of Sendero Luminoso.[13][14]

The Shining Path first established a foothold at San Cristóbal of Huamanga University, in Ayacucho, where Guzmán taught philosophy. The university had recently reopened after being closed for about half a century,[15] and many students of the newly educated class adopted the Shining Path's radical ideology. Between 1973 and 1975, Shining Path members gained control of the student councils at the Universities of Huancayo and La Cantuta, and they also developed a significant presence at the National University of Engineering in Lima and the National University of San Marcos. Sometime later, it lost many student elections in the universities, including Guzmán's San Cristóbal of Huamanga. It decided to abandon recruiting at the universities and reconsolidate.

Beginning on March 17, 1980, the Shining Path held a series of clandestine meetings in Ayacucho, known as the Central Committee's second plenary.[16] It formed a "Revolutionary Directorate" that was political and military in nature and ordered its militias to transfer to strategic areas in the provinces to start the "armed struggle". The group also held its "First Military School", where members were instructed in military tactics and the use of weapons. They also engaged in "Criticism and Self-criticism", a Maoist practice intended to purge bad habits and avoid the repetition of mistakes. During the existence of the First Military School, members of the Central Committee came under heavy criticism. Guzmán did not, and he emerged from the First Military School as the clear leader of the Shining Path.[17] In 1992, Guzmán and other leaders of the Shining Path received life imprisonment sentences for their role in the Lucanamarca massacre, among other charges.[18]

Guerrilla war

| People's Guerilla Army | |

|---|---|

Ejército Guerrillero Popular Participant in Internal conflict in Peru | |

| Active | 3 December 1982 – present |

| Ideology | Communism Marxism–Leninism–Maoism |

| Area of operations | Peru |

| Size | 350[19] |

| Part of | Communist Party of Peru – Shining Path |

| Opponent(s) | |

| Battles and war(s) | Tarata bombing Hatun Asha ambush Lucanamarca massacre |

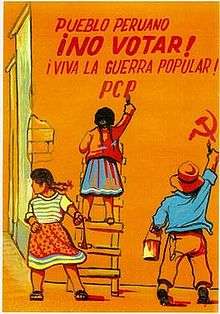

When Peru's military government allowed elections for the first time in a dozen years in 1980, the Shining Path was one of the few leftist political groups that declined to take part. It chose to begin guerrilla war in the highlands of the Ayacucho Region. On May 17, 1980, on the eve of the presidential elections, it burned ballot boxes in the town of Chuschi. It was the first "act of war" by the Shining Path. The perpetrators were quickly caught, and additional ballots were shipped to Chuschi. The elections proceeded without further problems, and the incident received little attention in the Peruvian press.[20]

Throughout the 1980s, the Shining Path grew, both in terms of the territory it controlled and in the number of militants in its organization, particularly in the Andean highlands. It gained support from local peasants by filling the political void left by the central government and providing what they called "popular justice", public trials that disregard any legal and human rights that deliver swift and brutal sentences, including public executions. This caused the peasantry of some Peruvian villages to express some sympathy for the Shining Path, especially in the impoverished and neglected regions of Ayacucho, Apurímac, and Huancavelica. At times, the civilian population of small, neglected towns participated in popular trials, especially when the victims of the trials were widely disliked.[21]

The Shining Path's credibility was helped by the government's initially tepid response to the insurgency. For over a year, the government refused to declare a state of emergency in the region where the Shining Path was operating. The Interior Minister, José María de la Jara, believed the group could be easily defeated through police actions.[22] Additionally, the president, Fernando Belaúnde Terry, who returned to power in 1980, was reluctant to cede authority to the armed forces since his first government had ended in a military coup. The result was that the peasants in the areas where the Shining Path was active thought the state was either impotent or not interested in their issues.

On December 29, 1981, the government declared an "emergency zone" in the three Andean regions of Ayacucho, Huancavelica, and Apurímac and granted the military the power to arbitrarily detain any suspicious person. The military abused this power, arresting scores of innocent people, at times subjecting them to torture during interrogation[23] as well as rape.[24] Police, military forces, and members of the Popular Guerrilla Army (Ejército Guerrillero Popular, or EGP) carried out several massacres throughout the conflict. Military personnel started to wear black ski-masks to hide their identities and protect their safety, and that of their families.

In some areas, the military trained peasants and organized them into anti-rebel militias, called "rondas". They were generally poorly equipped, despite being provided arms by the state. The rondas attacked the Shining Path guerrillas. The first such reported attack was in January 1983, near Huata, when ronderos killed 13 senderistas in February, in Sacsamarca. In March 1983, ronderos brutally killed Olegario Curitomay, one of the commanders of the town of Lucanamarca. They took him to the town square, stoned him, stabbed him, set him on fire, and finally shot him. The Shining Path's retaliation to this was brutal. In one of the worst attacks in the entire conflict, a group of guerrilla members came into town and going house by house, massacred dozens of villagers, including babies, with guns, hatchets, and axes. This action has come to be known as the Lucanamarca massacre.[25]

The Shining Path's attacks were not limited to the countryside. It mounted attacks against the infrastructure in Lima, killing civilians in the process. In 1983, it sabotaged several electrical transmission towers, causing a citywide blackout, and set fire and destroyed the Bayer industrial plant. That same year, it set off a powerful bomb in the offices of the governing party, Popular Action. Escalating its activities in Lima, in June 1985, it blew up electricity transmission towers in Lima, producing a blackout, and detonated car bombs near the government palace and the justice palace. It was believed to be responsible for bombing a shopping mall.[26] At the time, President Fernando Belaúnde Terry was receiving the Argentine president Raúl Alfonsín. In one of its last attacks in Lima, on July 16, 1992, the group detonated a powerful bomb on Tarata Street in the Miraflores District, full of civilian adults and children,[27] killing 25 people and injuring an additional 155.[28]

During this period, the Shining Path assassinated specific individuals, notably leaders of other leftist groups, local political parties, labor unions, and peasant organizations, some of whom were anti-Shining Path Marxists.[5] On April 24, 1985, in the midst of presidential elections, it tried to assassinate Domingo García Rada, the president of the Peruvian National Electoral Council, severely injuring him and mortally wounding his driver. In 1988, Constantin (Gus) Gregory,[29] an American citizen working for the United States Agency for International Development, was assassinated. Two French aid workers were killed on December 4 that same year.[30] In August 1991, the group killed one Italian and two Polish priests in the Ancash Region.[31] The following February, it assassinated María Elena Moyano, a well-known community organizer in Villa El Salvador, a vast shantytown in Lima.[32]

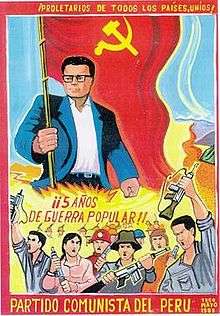

By 1991, the Shining Path had gained control of much of the countryside of the center and south of Peru and had a large presence in the outskirts of Lima. As the organization grew in power, a cult of personality grew around Guzmán. The official ideology of the Shining Path ceased to be "Marxism–Leninism–Mao Tse-tung thought" and was instead referred to as "Marxism–Leninism–Maoism–Gonzalo thought".[33] The Shining Path fought against Peru's other major guerrilla group, the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA),[34] as well as campesino self-defense groups organized by the Peruvian armed forces.

Although the reliability of reports regarding the Shining Path's atrocities remains a matter of controversy in Peru, the organization's use of violence is well documented. The Shining Path rejected the concept of human rights; a Shining Path document stated:

We start by not ascribing to either the Universal Declaration of Human Rights or the Costa Rica [Convention on Human Rights], but we have used their legal devices to unmask and denounce the old Peruvian state. [...] For us, human rights are contradictory to the rights of the people, because we base rights in man as a social product, not man as an abstract with innate rights. "Human rights" do not exist except for the bourgeois man, a position that was at the forefront of feudalism, like liberty, equality, and fraternity were advanced for the bourgeoisie of the past. But today, since the appearance of the proletariat as an organized class in the Communist Party, with the experience of triumphant revolutions, with the construction of socialism, new democracy and the dictatorship of the proletariat, it has been proven that human rights serve the oppressor class and the exploiters who run the imperialist and landowner-bureaucratic states. Bourgeois states in general. [...] Our position is very clear. We reject and condemn human rights because they are bourgeois, reactionary, counterrevolutionary rights, and are today a weapon of revisionists and imperialists, principally Yankee imperialists.

— Communist Party of Peru – Shining Path, Sobre las Dos Colinas[35]

Level of support

The Shining Path quickly seized control of large areas of Peru. The group had significant support among peasant communities, and it had the support of some slum dwellers in the capital and elsewhere. The Shining Path's Maoism probably did not have the support of many city dwellers. According to opinion polls, only 15% of the population considered subversion to be justifiable in June 1988, while only 17% considered it justifiable in 1991.[36] In June 1991, "the total sample disapproved of the Shining Path by an 83 to 7 percent margin, with 10 percent not answering the question. Among the poorest, however, only 58% stated disapproval of the Shining Path; 11 percent said they had a favorable opinion of the Shining Path, and some 31 percent would not answer the question."[37] A September 1991 poll found that 21 percent of those polled in Lima believed that the Shining Path did not torture and kill innocent people. The same poll found that 13% believed that society would be more just if the Shining Path won the war and 22% believed society would be equally just under the Shining Path as it was under the government.[37]

Polls have never been completely accurate since Peru has several anti-terrorism laws, including "apology for terrorism", that makes it a punishable offense for anyone who does not condemn the Shining Path. In effect, the laws make it illegal to support the group in any way.[38]

Many peasants were unhappy with the Shining Path's rule for a variety of reasons, such as its disrespect for indigenous culture and institutions.[39] However, they had also made agreements and alliances with some indigenous tribes. Some did not like the brutality of its "popular trials" that sometimes included "slitting throats, strangulation, stoning, and burning."[40][41] Peasants were offended by the rebels' injunction against burying the bodies of Shining Path victims.[42]

The Shining Path followed Mao Zedong's dictum that guerrilla warfare should start in the countryside and gradually choke off the cities.[43] The Shining Path banned continuous drunkenness, but they did allow the consumption of alcohol.

Government response

In 1991, President Alberto Fujimori issued a law that gave the rondas a legal status, and from that time, they were officially called Comités de auto defensa ("Committees of Self-Defense").[44] They were officially armed, usually with 12-gauge shotguns, and trained by the Peruvian Army. According to the government, there were approximately 7,226 comités de auto defensa as of 2005;[45] almost 4,000 are located in the central region of Peru, the stronghold of the Shining Path.

The Peruvian government also cracked down on the Shining Path in other ways. Military personnel were dispatched to areas dominated by the Shining Path, especially Ayacucho, to fight the rebels. Ayacucho, Huancavelica, Apurímac and Huánuco were declared emergency zones, allowing for some constitutional rights to be suspended in those areas.[46]

Initial government efforts to fight the Shining Path were not very effective or promising. Military units engaged in many human rights violations, which caused the Shining Path to appear in the eyes of many as the lesser of two evils. They used excessive force and killed many innocent civilians. Government forces destroyed villages and killed campesinos suspected of supporting the Shining Path. They eventually lessened the pace at which the armed forces committed atrocities such as massacres. Additionally, the state began the widespread use of intelligence agencies in its fight against the Shining Path. However, atrocities were committed by the National Intelligence Service and the Army Intelligence Service, notably the La Cantuta massacre, the Santa massacre and the Barrios Altos massacre, which were committed by Grupo Colina.[47][48]

After the collapse of the Fujimori government, interim President Valentín Paniagua established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to investigate the conflict. The Commission found in its 2003 Final Report that 69,280 people died or disappeared between 1980 and 2000 as a result of the armed conflict.[49] The Shining Path was found to be responsible for about 54% of the deaths and disappearances reported to the Commission.[50] A statistical analysis of the available data led the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to estimate that the Shining Path was responsible for the death or disappearance of 31,331 people, 46% of the total deaths and disappearances.[49] According to a summary of the report by Human Rights Watch, "Shining Path… killed about half the victims, and roughly one-third died at the hands of government security forces… The commission attributed some of the other slayings to a smaller guerrilla group and local militias. The rest remain unattributed."[51] The MRTA was held responsible for 1.5% of the deaths.[52] A 2019 study disputed the casualty figures from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, estimating instead "a total of 48,000 killings, substantially lower than the TRC estimate", and concluding that "the Peruvian State accounts for a significantly larger share than the Shining Path."[53][54]

Capture of Guzmán and collapse

On September 12, 1992, El Grupo Especial de Inteligencia (GEIN) captured Guzmán and several Shining Path leaders in an apartment above a dance studio in the Surquillo district of Lima. GEIN had been monitoring the apartment since a number of suspected Shining Path militants had visited it. An inspection of the garbage of the apartment produced empty tubes of a skin cream used to treat psoriasis, a condition that Guzmán was known to have. Shortly after the raid that captured Guzmán, most of the remaining Shining Path leadership fell as well.[55]

The capture of rebel leader Abimael Guzmán left a huge leadership vacuum for the Shining Path. "There is no No. 2. There is only Presidente Gonzalo and then the party," a Shining Path political officer said at a birthday celebration for Guzmán in Lurigancho prison in December 1990. "Without Presidente Gonzalo, we would have nothing."[56]

At the same time, the Shining Path suffered embarrassing military defeats to self-defense organizations of rural campesinos — supposedly its social base. When Guzmán called for peace talks, the organization fractured into splinter groups, with some Shining Path members in favor of such talks and others opposed.[57] Guzmán's role as the leader of the Shining Path was taken over by Óscar Ramírez, who himself was captured by Peruvian authorities in 1999. After Ramírez's capture, the group splintered, guerrilla activity diminished sharply, and peace returned to the areas where the Shining Path had been active.[58]

21st century resurgence and downfall

Although the organization's numbers had lessened by 2003,[58] a militant faction of the Shining Path called Proseguir ("Onward") continued to be active.[59]

On May 21, 2002, a car bomb exploded outside the US embassy in Lima just before a visit by President George W. Bush. Nine people were killed, and 30 were injured; the attack was determined to be the work of the Shining Path.[60]

On June 9, 2003, a Shining Path group attacked a camp in Ayacucho and took 68 employees of the Argentinian company Techint and three police guards as hostages. They had been working on the Camisea gas pipeline project that would take natural gas from Cusco to Lima.[61] According to sources from Peru's Interior Ministry, the rebels asked for a sizable ransom to free the hostages. Two days later, after a rapid military response, the rebels abandoned the hostages; according to government sources, no ransom was paid.[62] However, there were rumors that US$200,000 was paid to the rebels.[63]

Government forces have captured three leading Shining Path members. In April 2000, Commander José Arcela Chiroque, called "Ormeño", was captured, followed by another leader, Florentino Cerrón Cardozo, called "Marcelo", in July 2003. In November of the same year, Jaime Zuñiga, called "Cirilo" or "Dalton", was arrested after a clash in which four guerrillas were killed and an officer was wounded.[64] Officials said he took part in planning the kidnapping of the Techint pipeline workers. He was also thought to have led an ambush against an army helicopter in 1999 in which five soldiers died.

In 2003, the Peruvian National Police broke up several Shining Path training camps and captured many members and leaders.[65] By late October 2003, there were 96 terrorist incidents in Peru, projecting a 15% decrease from the 134 kidnappings and armed attacks in 2002.[65] Also for the year, eight[66] or nine[65] people were killed by the Shining Path, and 6 senderistas were killed and 209 were captured.[65]

In January 2004, a man known as Comrade Artemio and identifying himself as one of the Shining Path's leaders, said in a media interview that the group would resume violent operations unless the Peruvian government granted amnesty to other top Shining Path leaders within 60 days.[67] Peru's Interior Minister, Fernando Rospigliosi, said that the government would respond "drastically and swiftly" to any violent action. In September that same year, a comprehensive sweep by police in five cities found 17 suspected members. According to the interior minister, eight of the arrested were school teachers and high-level school administrators.[68]

Despite these arrests, the Shining Path continued to exist in Peru. On December 22, 2005, the Shining Path ambushed a police patrol in the Huánuco region, killing eight.[69] Later that day, they wounded an additional two police officers. In response, then President Alejandro Toledo declared a state of emergency in Huánuco and gave the police the power to search houses and arrest suspects without a warrant. On February 19, 2006, the Peruvian police killed Héctor Aponte, believed to be the commander responsible for the ambush.[70] In December 2006, Peruvian troops were sent to counter renewed guerrilla activity, and according to high-level government officials, the Shining Path's strength has reached an estimated 300 members.[71] In November 2007, police said they killed Artemio's second-in-command, a guerrilla known as JL.[72]

In September 2008, government forces announced the killing of five rebels in the Vizcatan region. This claim was subsequently challenged by the APRODEH, a Peruvian human rights group, which believed that those who were killed were in fact local farmers and not rebels.[73] That same month, Artemio gave his first recorded interview since 2006. In it, he stated that the Shining Path would continue to fight despite escalating military pressure.[74] In October 2008, in Huancavelica Region, the guerrillas engaged a military convoy with explosives and firearms, demonstrating their continued ability to strike and inflict casualties on military targets. The conflict resulted in the death of 12 soldiers and two to seven civilians.[75][76] It came one day after a clash in the Vizcatan region, which left five rebels and one soldier dead.[77]

In November 2008, the rebels utilized hand grenades and automatic weapons in an assault that claimed the lives of 4 police officers.[78] In April 2009, the Shining Path ambushed and killed 13 government soldiers in Ayacucho.[79] Grenades and dynamite were used in the attack.[79] The dead included eleven soldiers and one captain, and two soldiers were also injured, with one reported missing.[79]

Poor communications were said to have made relay of the news difficult.[79] The country's Defense Minister, Antero Flores Aráoz, said many soldiers "plunged over a cliff".[79] His Prime Minister, Yehude Simon, said these attacks were "desperate responses by the Shining Path in the face of advances by the armed forces" and expressed his belief that the area would soon be freed of "leftover terrorists".[79] In the aftermath, a Sendero leader called this "the strongest [anti-government] blow... in quite a while".[80] In November 2009, Defense Minister Rafael Rey announced that Shining Path militants had attacked a military outpost in southern Ayacucho province. One soldier was killed and three others wounded in the assault.[81]

On April 28, 2010, Shining Path rebels in Peru ambushed and killed a police officer and two civilians who were destroying coca plantations of Aucayacu, in the central region of Haunuco, Peru. The victims were gunned down by sniper fire coming from the thick forest as more than 200 workers were destroying coca plants.[82] Since this attack, the Shining Path faction, based in the Upper Huallaga Valley of Peru and headed by Florindo Eleuterio Flores Hala, alias Comrade Artemio, has been operating in a survival mode and has lost 9 of their top 10 leaders to Peruvian National Police (PNP)-led capture operations. Two of the eight leaders were killed by PNP personnel during the attempted captures. Those nine arrested/killed Shining Path (Upper Huallaga Valley faction) leaders include Mono (Aug. 2009), Rubén (May 2010), Izula (Oct. 2010), Sergio (Dec. 2010), Yoli/Miguel/Jorge (Jun. 2011), Gato Larry (Jun. 2011), Oscar Tigre (Aug. 2011), Vicente Roger (Aug. 2011), and Dante/Delta (Jan. 2012).[83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90]

This loss of leadership, coupled with a sweep of Shining Path (Upper Huallaga Valley) supporters executed by the PNP in November 2010, prompted Comrade Artemio to declare in December 2011 to several international journalists that the guerrilla war against the Peruvian Government has been lost and that his only hope was to negotiate an amnesty agreement with the Government of Peru.[91]

On February 12, 2012, Comrade Artemio was found badly wounded after a clash with troops in a remote jungle region of Peru. President Ollanta Humala said the capture of Artemio marked the defeat of the Shining Path in the Alto Huallaga valley – a center of cocaine production. President Humala has stated that he would now step up the fight against the remaining bands of Shining Path rebels in the Ene-Apurímac valley.[92] On March 3, Walter Diaz, the lead candidate to succeed Artemio,[93] was captured,[94] further ensuring the disintegration of the Alto Huallaga valley faction.[93] On April 3, 2012, Jaime Arenas Caviedes, a senior leader in the group's remnants in Alto Huallaga Valley[95] who was also regarded to be the leading candidate to succeed Artemio following Diaz's arrest,[96] was captured.[95] After Caviedes, alias "Braulio",[95] was captured, Humala declared that the Shining Path was now unable to operate in the Alto Huallaga Valley.[97]

On October 7, 2012, Shining Path rebels carried out an attack on three helicopters being used by an international gas pipeline consortium, in the central region of Cusco.[98] According to the military Joint Command spokesman, Col. Alejandro Lujan, no one was kidnapped or injured during the attack.[99]

On June 7, 2013, Comrade Artemio was convicted of terrorism, drug trafficking, and money laundering. He was sentenced to life in prison and a fine of $183 million.[100]

On August 11, 2013, Comrade Alipio, the Shining Path's leader in the Ene-Apurímac Valley, was killed in a battle with government forces in Llochegua.[101]

On April 9, 2016, on the eve of the country's presidential elections, the Peruvian government blamed remnants of the Shining Path for a guerilla attack that killed eight soldiers and two civilians.[102]

On March 18, 2017, Shining Path snipers killed three police officers in the Ene Apurimac Valley.[103]

Popular culture

- American hard rock band Guns N' Roses quotes a speech by a Shining Path officer in their 1990 song "Civil War", as saying "We practice selective annihilation of mayors and government officials, for example, to create a vacuum, then we fill that vacuum. As popular war advances, peace is closer."[104]

- The popular leftist rock band Rage Against the Machine explicitly supported the Shining Path in the music video of their popular song "Bombtrack", released in 1993, as well as in the lyrics of the track "Without a Face", released on their 1996 album Evil Empire.

- Philosopher J. Moufawad-Paul offers an extensive critique of the Shining Path in his theoretical Marxist work Continuity and Rupture, addressing what he considers to be the Shining Path's "degeneracy into personality cults, dogmatism, and terrorism."[105]

See also

- Maoism

- Definitions of terrorism

- List of designated terrorist groups

Notes

- Maske, Mahesh. "Maovichar", in Studies in Nepali History and Society, Vol. 7, No. 2 (December 2002), p. 275.

- Género y conflicto armado en el Perú, Sous la direction d’Anouk Guiné et de Maritza Felices-Luna

- "Shining-Path". Britannica.com. Accessed September 13, 2018.

- Truth and Reconciliation. Accessed September 13, 2018.

- Burt, Jo-Marie (2006). "'Quien habla es terrorista': The political use of fear in Fujimori's Peru." Latin American Research Review 41 (3) 32-62.

- "MOFA: Implementation of the Measures including the Freezing of Assets against Terrorists and the Like". Archived from the original on April 6, 2013. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- United States Department of State, April 30, 2007. "Terrorist Organizations". Retrieved June 11, 2009.

- Council Common Position 2005/936/CFSP.. March 14, 2005. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- Government of Canada. "Listed Entities" Archived November 19, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved June 11, 2009.

- Rochlin, p. 3.

- Roncagliolo, Santiago (2007). "3 - Por el Sendero Luminoso de Mariátegui" [3 - On the Shining Path of Mariategui]. La cuarta espada : la historia de Abimael Guzmán y Sendero Luminoso [The Fourth Sword: The History of Abimael Guzman and the Shining Path] (5 ed.). Buenos Aires: Debate. p. 78. ISBN 9789871117468. OCLC 225864678.

"Y en su fundación de 1969 sólo eran doce personas." "And at the founding in 1969, they were only 12 people."

- Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. Book II Chapter 1 page 16. Retrieved June 11, 2009.

- Colin Harding, “Antonio Díaz Martínez and the Ideology of Sendero Luminoso,” Bulletine for Latin American Research 7#1 (January 1988) pp 65–73.

- Julia Lovell, Maoism: A Global History (2019) pp 306–346.

- "Reseña Histórica" [Historical Overview]. UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE SAN CRISTÓBAL DE HUAMANGA (in Spanish). Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

"Con auspicios de la corona española y del Poder Pontificio, el 3 de julio de 1677 el obispo de la Diócesis de Huamanga, don Cristóbal de Castilla y Zamora, fundó la 'Universitas Guamangensis Sancti Christhophosi' [...] Clausurada en 1886 y reabierta 80 años después, reiniciando sus labores académicas el 3 de julio de 1959 como 'Universidad Nacional de San Cristóbal de Huamanga.'" "Closed in 1886 and reopened 80 years later, it restarted its academic work July 3rd, 1959 as the 'National University of Saint Christopher of Huamanga.'"

- Gorriti, p. 21.

- Gorriti, pp. 29–36.

- La República. October 13, 2006. Abimael Guzmán y Elena Iparraguirre pasarán el resto de sus vidas en prisión. Accessed February 11, 2008.

- "Shining Path is Back". August 18, 2015. Archived from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- Gorriti, p. 17.

- Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. Book VI Chapter 1 page 41. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. Book III Chapter 2 pages 17–18. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- Amnesty International. "Peru: Summary of Amnesty International's concerns 1980 – 1995" Archived March 30, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- Human Rights Watch "The Women's Rights Project." . Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. August 28, 2003. "La Masacre de Lucanamarca (1983)". (in Spanish) Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- Human Rights Watch. Peru: Human Rights Developments. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- "Ataque terrorista en Tarata." Archived online. Retrieved January 16, 2008

- Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. Los Asesinatos y Lesiones Graves Producidos en el Atentado de Tarata (1992). p. 661. Retrieved February 9, 2008.

- Beyette, Beverly (July 7, 1988). "A Most Unlikely Target : Good Samaritan Aiding the Peruvian Poor Became a Casualty in the Nation's Political Struggle". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- Stéphane Courtois et al. The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Harvard University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-674-07608-7 p. 677

- Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. Annex 1 page 190. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- Burt, Jo-Marie. "The Shining Path and the Decisive Battle in Lima's Barriadas: The Case of Villa El Salvador, p 291 in Shining and Other Paths: War and Society in Peru, 1980–1995, ed. Steve Stern, Duke University Press: Durham and London, 1998 (ISBN 0-8223-2217-X).

- Gorriti, p. 185.

- Manrique, Nelson. "The War for the Central Sierra," p. 211 in Shining and Other Paths: War and Society in Peru, 1980–1995, ed. Steve Stern, Duke University Press: Durham and London, 1998 (ISBN 0-8223-2217-X).

- Communist Party of Peru. "Sobre las Dos Colinas" Part 3 Archived November 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine and Part 5 Archived September 1, 2006, at the Wayback Machine available online. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- Kenney, Charles D. 2004. Fujimori's Coup and the Breakdown of Democracy in Latin America. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame. Citing Balibi, C.R. 1991. "Una inquietante encuesta de opinión." Quehacer: 40–45.

- Kenney, Charles D. 2004. Fujimori's Coup and the Breakdown of Democracy in Latin America. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame.

- Sandra Coliver, Paul Hoffman, Joan Fitzpatrick, Stephen Bowman, Secrecy and Liberty: National Security, Freedom of Expression and Access To Information, (Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague Publishers,) 1999, P. 162.

- Del Pino H., Ponciano. "Family, Culture, and 'Revolution': Everyday Life with Sendero Luminoso," p. 179 in Shining and Other Paths: War and Society in Peru, 1980–1995, ed. Steve Stern, Duke University Press: Durham and London, 1998 (ISBN 0-8223-2217-X).

- U.S. Department of State. March 1996 "Peru Human Rights Practices, 1995". Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- Starn, Orin. "Villagers at Arms: War and Counterrevolution in the Central-South Andes," p. 237 in Shining and Other Paths: War and Society in Peru, 1980–1995, ed. Steve Stern, Duke University Press: Durham and London, 1998 (ISBN 0-8223-2217-X).

- Degregori, p. 140.

- Desarrollar la lucha armada del campo a la ciudad, San Marcos 1985 PCP speech

- Legislative Decree No. 741. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- Army of Peru (2005). Proyectos y Actividades que Realiza la Sub Dirección de Estudios Especiales.". Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- "Government Declares State of Emergency with Curfew in Lima". AP NEWS. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- La Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. August 28, 2003. "2.45. Las Ejecuciones Extrajudiciales en Barrios Altos (1991.)" Available online in Spanish. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- La Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. August 28, 2003. "2.19. La Universidad Nacional de educación Enrique Guzmán y Valle «La Cantuta»." Available online in Spanish. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. Annex 2 Page 17. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. Book I Part I Page 186. Retrieved January 14, 2008

- Human Rights Watch. August 28, 2003. "Peru – Prosecutions Should Follow Truth Commission Report". Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- Laura Puertas, Inter Press Service. August 29, 2003. Peru: 20 Years of Bloodshed and Death" Archived March 21, 2004, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- Rendon, Silvio (January 1, 2019). "Capturing correctly: A reanalysis of the indirect capture–recapture methods in the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission". Research & Politics. 6 (1): 2053168018820375. doi:10.1177/2053168018820375. ISSN 2053-1680.

- Rendon, Silvio (April 1, 2019). "A truth commission did not tell the truth: A rejoinder to Manrique-Vallier and Ball". Research & Politics. 6 (2): 2053168019840972. doi:10.1177/2053168019840972. ISSN 2053-1680.

- Rochlin, p. 71.

- "Guzman arrest leaves Void in Shining Path Leadership" Associated Press/Deseret News.com, September 14, 1992

- Sims, Calvin (August 5, 1996) "Blasts Propel Peru's Rebels From Defunct To Dangerous.". The New York Times. Retrieved January 17, 2008

- Rochlin, pp. 71–72.

- United States Department of State (2005). Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Peru – 2005. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- "Peru bomb fails to deter Bush". BBC. March 21, 2002. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- "Pipeline Workers Kidnapped". The New York Times, June 10, 2003. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- "Peru hostages set free". BBC, June 11, 2003. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- "Gas Workers Kidnapped, Freed" Americas.org. Retrieved January 17, 2008

- "Peru Captures Shining Path Rebel.". BBC News, November 9, 2003. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- United States Department of State, Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism. April 29, 2004. "Patterns of Global Terrorism: Western Hemisphere Overview" . Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- United States Department of State. February 25, 2004. Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – 2003: Peru. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- Issue Papers and Extended Responses. Available online Archived December 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- "En operativo especial capturan a 17 requisitoriados por terrorismo" Archived March 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. La República, September 29, 2004. Retrieved January 16, 2008. (in Spanish)

- "Rebels Kill 8 Policemen". The New York Times, December 22, 2005. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- "Jefe militar senderista ‘Clay’ muere en operativo policial" Archived March 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. La República, February 20, 2006. Retrieved January 20, 2008. (in Spanish)

- Washington Times. December 12, 2006. "Troops dispatched to corral guerrillas."

- "Peru police 'kill leading rebel'" . BBC. Retrieved January 13, 2008.

- "Peru army may have killed farmers – rights group". Reuters. Retrieved June 11, 2009.

- "Peru rebel leader refuses to lay down arms". AP. Retrieved June 11, 2009.

- "Peru rebels launch deadly ambush'". BBC. Retrieved June 11, 2009.

- "Peru says 14 killed in Shining Path attack" Archived October 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Associated Press. Retrieved June 11, 2009.

- "1 Peruvian soldier, 5 rebels killed in military campaign". Associated Press. Retrieved June 11, 2009.

- "Peru's Shining Path kill four police in ambush". AFP. Retrieved June 11, 2009.

- "Rebels kill 13 soldiers in Peru". BBC. Retrieved April 12, 2009.

- "Shining Path rebels stage comeback in Peru". CNN. April 21, 2009. Retrieved April 24, 2009.

- "Peru rebels attack army outpost, killing 1 soldier". Associated Press. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- "Peru rebels ambush and kill coca plantation clearers". BBC, April 28, 2010

- "Senderista 'Izula' es responsable del secuestro y asesinato de 40 civiles | El Comercio Perú". Elcomercio.pe. October 13, 2010. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- "Policía Nacional capturó a cabecilla terrorista 'Sergio' en el Alto Huallaga | El Comercio Perú". Elcomercio.pe. December 30, 2010. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- "Policía Nacional del Perú". Pnp.gob.pe. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- "Cae terrorista sindicado como el N° 3 de Sendero en el Huallaga". LaRepublica.pe. April 17, 2014. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 9, 2012. Retrieved January 22, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 10, 2012. Retrieved January 22, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- DELTA. "Detenido el proveedor de armas a terroristas del Alto Huallaga". LaRepublica.pe. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- "Cae terrorista cercano a 'Artemio' | Actualidad". Peru21.pe. January 9, 2012. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- "Entrevista con senderista 'Artemio': "No vamos a realizar más ataques" | El Comercio Perú". Elcomercio.pe. December 7, 2011. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- "Peru Shining Path leader Comrade Artemio captured". BBC News. February 13, 2012.

- Christopher Looft (March 5, 2012). "Peru Arrests 'Successor' to Captured Shining Path Leader". Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- "Peruvian police capture 'Shining Path boss' Walter Diaz". BBC News. March 4, 2012.

- Andean Air Mail & Peruvian Times (April 5, 2012). "Peru Captures Shining Path Leader In Upper Huallaga". Peruvian Times. Retrieved April 5, 2012.

- Archived April 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Shining Path 'defeated' in Alto Huallaga stronghold". BBC News. April 6, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- "Peru rebels burn helicopters at jungle airfield". BBC News. BBC. October 7, 2012. Retrieved October 9, 2012.

- "Rebels Burn 3 Helicopters in Peru". ABC News. Archived from the original on October 7, 2012.

- "Peru's Shining Path leader jailed for life for terrorism." BBC News. June 7, 2013. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- "Alejandro Borda Casafranca, 2 other Senderistas killed in Peru". United Press International. August 13, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- "Death toll climbs to 10 in Peru guerrilla attack on election eve" Tico Times. April 11, 2016. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- Goi, Leonardo. "Recent Attack on Peru Police Shows Shining Path Still Strong". www.insightcrime.org. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- de Lama, George (July 9, 1989). "'More War Will Bring Peace,' Say Peru's Maoists After 15,000 Die". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- Moufawad-Paul, J. (2016). Contitunity and Rupture. Zero Books.

References

- Courtois, Stephane (1999). The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Harvard University Press.

- Crenshaw, Martha, "Theories of Terrorism: Instrumental and Organizational Approaches" in: Inside Terrorist Organizations, (ed. David Rapoport), 2001. Franck Cass, London

- Degregori, Carlos Iván (1998). "Harvesting Storms: Peasant Rondas and the Defeat of Sendero Luminoso in Ayacucho". In Steve Stern (Ed.), Shining and Other Paths: War and Society in Peru, 1980–1995. Durham and London: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-2217-X. ISBN 978-0-8223-2217-7.

- Gorriti, Gustavo (1999). The Shining Path: A History of the Millenarian War in Peru. Trans. Robin Kirk. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4676-7

- Isbell, Billie Jean (1994). "Shining Path and Peasant Responses in Rural Ayacucho". In Shining Path of Peru, ed. David Scott Palmer. 2nd Edition. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-10619-X

- Isbell, J (1994). Shining Path and Peasant Responses in Rural Ayacucho en Shining Path of Per (1st ed.) New York.

- Koppel, Martin. Peru's 'Shining Path' Evolution of a Stalinist Sect (1994)

- Palmer, David Scott. ed. The Shining Path of Peru (2nd ed 1994) excerpt

- Rochlin, James F (2003). Vanguard Revolutionaries in Latin America: Peru, Colombia, Mexico. Boulder and London: Lynne Rienner Publishers: ISBN 1-58826-106-9.

- Laqueur, W. (1999). The new terrorism: Fanaticism and the arms of mass destruction. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lovell, Julia. Maoism: A Global History (2019) pp 306–346 on Peru.

- Rochlin, J. F. (2003). Vanguard revolutionaries in Latin America: Peru, Colombia, Mexico. Boulder, Colo: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Starn, Orin. "Maoism in the Andes: The Communist Party of Peru-Shining Path and the refusal of history." Journal of Latin American Studies 27.2 (1995): 399-421. online

- Comisión de la verdad y reconciliación (2003). La verdad después del silencio (Informe final tomo 6). Lima. Perú

- Martín-Baró, I. (1988) El Salvador 1987. Estudios Centroamericanos (ECA), No. 471-472, pp. 21–45

- Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación (2003). Informe Final. Lima: CVR. (in Spanish)

Fiction

- The Vision of Elena Silves: A Novel by Nicholas Shakespeare

- The Dancer Upstairs: A Novel by Nicholas Shakespeare, ISBN 0-385-72107-2.

- The Dancer Upstairs movie listing from the Internet Movie Database

- Detective First Grade, by Dan Mahoney, ISBN 978-0-312-95313-3.

- Edge of the City, by Dan Mahoney, ISBN 978-0-312-95788-9.

- Strange Tunnels Disappearing by Gary Ley, ISBN 1-85411-302-X.

- The Evening News, by Arthur Hailey, ISBN 0-385-50424-1.

- Death in the Andes, by Mario Vargas Llosa, ISBN 0-14-026215-6.

- "The Road Back Home" (El camino de regreso) by José de Piérola, ISBN 978-9972-09-002-8

- "A Kiss from Hell" (Un beso del infierno) by José de Piérola, ISBN 978-9972-09-318-0

- Paper Dove (Paloma de Papel) movie listing from the Internet Movie Database

- La Trinchera Luminosa del Presidente Gonzalo

- "War Cries", a first-season episode of JAG.

- Corner of the Dead by Lynn Lurie, University of Massachusetts Press (winner of the Juniper Prize for Fiction)

- Escape from L.A. a movie starring Kurt Russell

- "Red April": a novel by Santiago Roncagliolo

- The Intelligent Homosexual's Guide to Capitalism and Socialism with a Key to the Scriptures, a play by Tony Kushner

External links

- The People's War in Perú Archive – Information about the Communist Party of Perú (PCP) 'Shining Path' Official Site until 1998

- Article by Caretas comparing Tarata to the 9/11 attack by Al Qaeda

- Article in PDF about the Tarata Car Bomb by the Shining Path

- New 'Shining Path' threat in Peru, on the April 2004 interview with Artemio

- (in Spanish) Shining Path communiqués on the web site of the "Partido Comunista de España [Maoista]"

- (in Spanish) Report of the (CVR) Truth and Reconciliation Commission (PDF)

- (in Spanish) Report of the (CVR) Truth and Reconciliation Commission (HTML)

- Terrorism Research Center list of Terrorist Organizations.

- The assassination of Maria Elena Moyano

- Peru: The killings of Lucanamarca BBC, October 14, 2006

- Committee to Support the Revolution in Peru

- Peru and the Capture of Abimael Guzman, Congressional Record, (Senate—October 2, 1992)

- The Search for Truth: The Declassified Record on Human Rights Abuses in Peru. Edited by Tamara Feinstein, Director, Peru Documentation Project