Pedestrian crossing

A pedestrian crossing (primarily British English) or crosswalk (primarily American English) is a place designated for pedestrians to cross a road, street or avenue. Pelican crosswalks are designed to keep pedestrians together where they can be seen by motorists, and where they can cross most safely across the flow of vehicular traffic.

The wording pedestrian crossing is used in some international treaties on road traffic and road signs, such as the Vienna Convention on Road Traffic and the Vienna Convention on Road Signs and Signals.

Marked pedestrian crossings are often found at intersections, but may also be at other points on busy roads that would otherwise be too unsafe to cross without assistance due to vehicle numbers, speed or road widths. They are also commonly installed where large numbers of pedestrians are attempting to cross (such as in shopping areas) or where vulnerable road users (such as school children) regularly cross. Rules govern usage of the pedestrian crossings to ensure safety; for example, in some areas, the pedestrian must be more than halfway across the crosswalk before the driver proceeds.

Signalised pedestrian crossings clearly separate when each type of traffic (pedestrians or road vehicles) can use the crossing. Unsignalised crossings generally assist pedestrians, and usually prioritise pedestrians, depending on the locality. What appears to be just pedestrian crossings can also be created largely as a traffic calming technique, especially when combined with other features like pedestrian priority, refuge islands, or raised surfaces.

History

Pedestrian crossings already existed more than 2000 years ago, as can be seen in the ruins of Pompeii. Blocks raised on the road allowed pedestrians to cross the street without having to step onto the road itself which doubled up as Pompeii's drainage and sewage disposal system. The spaces between the blocks allowed horse-drawn carts to pass along the road.[2]

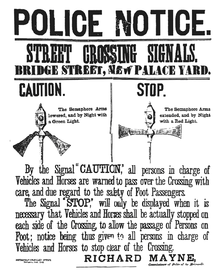

The first pedestrian crossing signal was erected in Bridge Street, Westminster, London, in December 1868. It was the idea of John Peake Knight, a railway engineer, who thought that it would provide a means to safely allow pedestrians to cross this busy thoroughfare. The signal consisted of a semaphore arm (manufactured by Saxby and Farmer, who were railway signaling makers), which was raised and lowered manually by a police constable who would rotate a handle on the side of the pole. The semaphore arms were augmented by gas illuminated lights at the top (green and red) to increase visibility of the signal at night. However, in January 1869, the gas used to illuminate the lights at the top leaked and caused an explosion, injuring the police operator. No further work was done on signalled pedestrian crossings until fifty years later.[3]

In the early 20th century, car traffic increased dramatically. A reader of The Times wrote to the editor in 1911:

"Could you do something to help the pedestrian to recover the old margin of safety on our common streets and roads? It is heartrending to read of the fearful deaths taking place. If a pedestrian now has even one hesitation or failure the chance of escape from a dreadful death is now much less than when all vehicles were much slower. There is, too, in the motor traffic an evident desire not to slow down before the last moment. It is surely a scandal that on the common ways there should be undue apprehension in the minds of the weakest users of them. While the streets and roads are for all, of necessity the pedestrians, and the feeblest of these, should receive the supreme consideration."[4]

According to Zegeer,

"Pedestrians have a right to cross roads safely and, therefore, planners and engineers have a professional responsibility to plan, design, and install safe crossing facilities."[5]

Installation criteria

Some Countries have specific criteria to provide pedestrian facilities; for example, they provide warrants, depending on local conditions, usually prioritized as follows:

a) Do nothing. In most places, the pedestrian does not need specific facilities, as in low car flow streets, the pedestrians can cross (without priority) at any location.

b) providing central islands in the road. Provides the pedestrian with a safe place to wait at the middle of the road and advance as conditions permit.

c) Central reservation. A continuous (Usually raised) central reservation promotes safe pedestrian crossing in all the area, and reduce vehicle speed and head-on crash.

d) Zebra crossing. Provides a crossing in a low pedestrians flow area, if the pedestrian flow is high (as outside a school, train or bus terminal) the vehicle traffic will be severally affected by a significant number of pedestrians using the crossing, making necessary to provide traffic signals.

e) Traffic signals (Pelican in the U.K.). Used to control vehicle-pedestrian conflicts, not in intersections, and provided with pedestrians buttons. In this way, the vehicle signal turns red only if a pedestrian is trying to cross.

g) A staggered traffic signal. If the road is wide, (two or more traffic lines per traffic direction) and a central reservation exists or can be provided, traffic signals can be installed in a not aligned pair. This design permits to provide staggered green time for pedestrians (one side can be green while the other is red), The pedestrian needs to wait in the central reservation for the second crossing, improving the possibility to coordinate vehicle traffic between intersection, with a reduction of stops, fuel consumption, and reduced car emissions.

h) Pedestrian signal in the intersection. This facility is added in an intersection with a traffic signal, giving a clear orientation to a pedestrian when it is possible to cross. In some countries, is provision is obligatory in all traffic signals.

i) Pedestrian overpass or underpass. This facility eliminates the conflict between vehicular traffic and pedestrian, but need to be supported by some form of physical restriction preventing pedestrians from crossing at level, as they perceived the additional effort to climb the overpass.

Design and layout

Unmarked crossings may occur at any intersection, except at locations where pedestrian crossing is expressly prohibited. In the US these are called "unmarked crosswalks."[6]

The simplest marked crossings may just consist of some markings on the road surface. In the US these are known as "marked crosswalks."[6] In the UK these are often called zebra crossings, referring to the alternate white and black stripes painted on the road surface.[7] If the pedestrian has priority over vehicular traffic when using the crossing, then they have an incentive to use the crossing instead of crossing the road at other places. In some countries, pedestrians may not have priority, but may be committing an offence if they cross the road elsewhere, or "jaywalk." Special markings are often made on the road surface, both to direct pedestrians and to prevent motorists from stopping vehicles in the way of foot traffic. There are many varieties of signal and marking layouts around the world and even within single countries. In the United States, there are many inconsistencies, although the variations are usually minor. There are several distinct types in the United Kingdom, each with their own name.

Some crossings have pedestrian traffic signals that allow pedestrians and road traffic to use the crossing alternately. On some traffic signals, pressing a call button is required to trigger the signal.[8][9] Audible or tactile signals may also be included to assist people who have poor sight.[10] In many cities, some or most signals are equipped with countdown timers to give notice to both drivers and pedestrians the time remaining on the crossing signal.[10] In places where there is very high pedestrian traffic, Embedded pavement flashing-light systems are used to signal traffic of pedestrian presence, or exclusive traffic signal phases for pedestrians (also known as Barnes Dances) may be used, which stop vehicular traffic in all directions at the same time.[11][12]

Footbridges and tunnels

Footbridges or pedestrian tunnels may be used in lieu of crosswalks at very busy intersections as well as at locations where limited-access roads and controlled-access highways must be crossed. They can also be beneficial in locations where the sidewalk or pedestrian path naturally ascends or descends to a different level than the intersection itself, and the natural "desire line" leads to a footbridge or tunnel, respectively.[13] However, pedestrian bridges are ineffective in most locations; due to their expense, they are typically spaced far apart. Additionally, ramps, stairs, or elevators present additional obstacles, and pedestrians tend to use an at-grade pedestrian crossing instead, sometimes jaywalking to avoid these obstacles.[13] A variation on the bridge concept, often called a skyway or skywalk, is sometimes implemented in regions that experience inclement weather.

Pedestrian scramble

.jpg)

Some intersections display red lights in all directions for a period of time. Known as a pedestrian scramble, this type of vehicle all-way stop allows pedestrians to cross safely in any direction, including diagonally.

Crosswalk shortening

Pedestrian refuges or small islands in the middle of a street may be added when a street is very wide, as these crossings can be too long for some individuals to cross in one cycle.[14] These pedestrian refuges may consist of building new concrete traffic islands in the middle of the road; extending an existing island or median strip to the crosswalk to provide a refuge; or simply cutting through the existing island or median strip where the median is already continuous.[14]

Another relatively widespread variation is the curb/kerb extension (also known as a bulb-out), which narrows the width of the street and is used in combination with crosswalk markings. They can also be used to slow down cars, potentially creating a safer crossing for pedestrians.[15]

Crosswalk striping

Pedestrian cross striping machines are special equipment professionally used to paint zebra lines on the intersections or other busy road sections. Because of the characteristics of zebra crossings, parallel stripes that are wide but not long, the striping machine is often a small hand-guided road marking machine, which can easily be made to change direction. There are differences between the engineering regulations in different countries. The marking shoe of a pedestrian cross striping machine, which determines marking lines' width, is much wider than on other marking machines. A smaller marking shoe with wheels may be used to perform the road striping.

The section of road should be swept clean and kept dry. The painter first pulls a guiding line straight and fix the two ends on the ground. Then they spray or brush a primer layer on the asphalt or concrete surface. The thermoplastic paint in powder form is then melted into a molten liquid state for painting. Finally, the painter pulls or pushes the striping machine with the guide rod along the guiding line. As an alternative to thermoplastics, household paint or epoxy can be used to mark crosswalks.[16]

Crosswalks as artwork

Some crosswalks include unique designs, many of which take the form of artwork. These works of art may serve many different purposes, such as attracting tourism or catching drivers' attention.[17]

Cities and towns worldwide have held competitions to paint crosswalks, usually as a form of artwork.[17] In Santiago, a 2013 work by Canadian artist Roadsworth features yellow-and-blue fish overlaid on the existing crosswalk. Other crossings worldwide also feature some of Roadsworth's work,[18] including a crosswalk in Montreal where the zebra stripes are shaped like bullets, as well as "conveyor belt" crosswalk in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.[17] In Lompoc, California, several artists were commissioned to create an artwork as part of its "Creative Crossings" competition. Artist Marlee Bedford painted the first set of four crosswalks as part of the 2015 competition,[19] and Linda Powers painted two more crosswalks in 2016 following that year's competition.[20]

In Tbilisi, some Tbilisi Academy of Arts students and government officials jointly created a crossing that is designed to look like it is in 3D. A message on the white bars of the crosswalk reads, "for your safety."[17][21] 3D crosswalk designs have also been installed in China, with a "floating zebra crossing" implemented in a village in Luoyuan County to boost tourism;[17] a multicolored 3-D crossing installed in Changsha to catch drivers' attention;[22] and another multicolored crossing in Sichuan that serves the same purpose as the colored Changsha crosswalk.[23]

Colored crosswalks might have themes that reflect the immediate area. For instance, Chengdu had a red-and-white zebra crossing with hearts painted on it, reflecting its location near a junction of two rivers.[24][17][23] In Curitiba, a crosswalk with its bars irregularly painted like a barcode served as an advertisement for a nearby shopping center, but was later painted over.[23] A pedestrian scramble in the Chinatown section of Oakland, California, is painted with red-and-yellow colors to signify the colors of the flag of China.[23][25]

Sometimes, different cities around the world may have similar art concepts for their crosswalks. Rainbow flag-colored crosswalks, which are usually painted to show support for the locality's LGBT cultures, have been installed in San Francisco;[26][17] West Hollywood;[27] Philadelphia;[28] and Tel Aviv.[29][17] Crosswalks painted like piano keyboards have been painted in Long Beach;[30] Warsaw;[17][23] and Chongqing.[17]

The United States Federal Highway Administration prohibits crosswalk art due to concerns about safety and visibility, but U.S. cities have chosen to install their own designs. Seattle had 40 crosswalks with unique designs, including the rainbow flag in Capitol Hill and the Pan-African flag in the Central District.[31][32]

Distinctions by region

North America

For crosswalk safety, in the USA there is not much clarity regarding the need for a crosswalk to be marked or unmarked dues to advantages and disadvantages of both approaches, although each city might have its own rules.[5]

Marked crosswalks

.svg.png)

In the United States, crosswalks are sometimes marked with white stripes, though many municipalities have slightly different methods, styles, or patterns for doing so. The designs used vary widely between jurisdictions, and often vary even between a city and its county (or local equivalents).[33][34] There are two main methods for road markings in the United States, as mandated by the 2009 version of the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD). Most frequently, they are marked with two parallel white lines running from one side of the road to the other, with the width of the lines being typically 12 to 24 inches (300 to 610 mm) wide.[33][34] A third "stop line", which is about the same thickness and extends only across lanes going into the intersection, is usually also present. The stop line acts as the legally mandated stopping point for vehicles, and discourages drivers from stopping in the middle of the crosswalk.[34] The other method involves the use of the more easily visible "continental stripes" (like the UK's zebra crossings), which are sets of multiple bars across the crosswalk itself that are perpendicular to the direction of crossing. These bars are typically 12 to 24 inches (300 to 610 mm) wide and are set 12 to 24 inches (300 to 610 mm) apart. Crosswalks can use a combination of two parallel white lines and continental stripes to create a "ladder" crosswalk, which is highly visible.[33][34]

Marked crosswalks are usually placed at traffic intersections or crossroads, but are occasionally used at mid-block locations where pedestrian generators are present such as at transit stops, schools, retail, or housing destinations. In the United States, these "mid-block crossings" may include additional regulatory signage such as "PED XING" (for "pedestrian crossing"), flashing yellow beacons, stop or yield signs, or by actuated or automatic signals.[33] Some more innovative crossing treatments include in-pavement flashers, yellow flashing warning lights installed in the roadway, or HAWK beacon—an overhead signal with a pair of red beacons above an amber beacon, when a pedestrian is detected or actuates the device it begins a sequence of amber flashing followed by a solid red, followed by a flashing red phase that allows motorists to proceed, only if the pedestrian(s) are clear of the travel way.[35]

In the United States, crossing laws vary from state to state and sometimes at the local level. All states require vehicles to yield to a pedestrian who has entered a marked crosswalk.[6] Legally speaking, in most states crosswalks exist at all intersections meeting at approximately right angles, whether they are marked or not.[36] All states except Maine and Michigan require vehicles to yield to a pedestrian who has entered an unmarked crosswalk.[6] To gain the right-of-way in some parts of Canada, however, the pedestrian holds out his hand in a position much like that used to shake hands, and steps off the curb. The province of Ontario enacted a law in 2016 that mandates that drivers and bicyclists come to a complete stop at pedestrian "crossovers"—ladder-style crosswalks that are sometimes designated with overhead signs or lights—as well as crosswalks with school crossing guards.[37]

Signalized intersections

.jpg)

- The signal at left displays a "steady upraised hand" signal, which indicates "don't walk".

- The signal at center displays a "steady walking man" signal, which indicates "walk".

- The signal at right displays a "flashing upraised hand" signal, which indicates that "don't walk" is imminent. This is accompanied by a countdown timer as per the 2009 MUTCD.

At crossings controlled by signals, the most common variety is arranged like this: At each end of a crosswalk, the poles which hold the traffic lights also have white "walk" and Portland Orange "don't walk" signs.[38] These particular colors are used in North America (excluding Quebec[39]) to provide conspicuity against the backdrop of red, yellow, and green traffic lights. As of the 2000 MUTCD, modern signals are mandated to use pictograms of an orange "upraised hand" and a white "walking man" rather than words;[38] the hand/man display is the mandate as of the 2009 edition.[10] On pedestrian signals displaying text, "don't walk" is spelled without an apostrophe so that it fits easily on the sign.[40] Modern pedestrian signals can be incandescent, neon, fiber-optic, or LED, with the latter three displays typically utilizing less energy.[41]

Regardless of whether pictograms or words are used, the MUTCD defines a steady "upraised hand" or "don't walk" signal as an indication that a pedestrian cannot enter the street in that signal's direction, while a steady "walking man" or "walk signal" indicates that pedestrians can start crossing the street toward that signal.[10] The upraised hand or "don't walk" signals begin to flash during the pedestrian clearance interval when the transition to "don't walk" is imminent.[10] This normally occurs several seconds before the light turns yellow, usually going solid orange when the traffic light turns yellow or red; however, the display can be turned into a steady hand or "don't walk" sign while the vehicular light is yellow, or while the vehicular signal is still displaying a green light.[42] In intersections with "leading pedestrian intervals," the upraised hand or "don't walk" sign will continue flashing as the vehicular lights turn red and the other crossing(s) in the intersection display a walking man or "walk" sign. The vehicular traffic is then stopped in all directions for a short period of time before cross traffic is allowed to proceed.[43] The 2009 MUTCD states that the flashing walking man or "walk" signals do not have meaning.[10] The "flashing walk" indication was formerly used to delineate "watch out for turning vehicles"[44] and is still in use in Washington, D.C.;[45] however, as of the 2003 MUTCD, this was replaced by an optional "animated eyes" indication within the pedestrian signal display,[46][47] which was placed in the MUTCD following a study that recommended the usage of the "animated eyes" signal.[48]

A gridded "egg-crate visor" (U.S. Patent 3,863,251) is customarily placed in front of the lights to shield them from the sun and increase their visibility, but such visors can also be vulnerable to snow or ice accumulation on the screens, which in turn could block the pedestrian display.[41] Pedestrian signals can also use a triangular-prism-shaped "cutaway visor" or "cap visor" (so named because the pitch of the visor, is shaped like a baseball cap), which mainly covers the top of the signal and the tops of the left and right sides; or a more rectangular-shaped "tunnel visor", which fully covers the left, right, and top sides of the pedestrian display.[49][50]

In some cities in the US, other methods of pedestrian detection are being or have been tested, including infrared and microwave technology, as well as weight sensors built in at curbside.[51] A 2000 study of these detectors in Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Rochester found that the infrared and microwave technologies both helped reduce conflicts between pedestrians and turning vehicles, as well as pedestrians starting during the "don't walk" phase.[52][53]:38–39 Subsequent studies found that the efficacy of these sensors varied based on pedestrian traffic at the location where they were installed.[53]:39–40

On fully actuated signals, or semi-actuated traffic signals, pressing the button to cross a smaller side street will cause an "instant walk signal". In most states, drivers only have to wait until the pedestrian has finished crossing the half of the crosswalk that the driver is driving on, after which the driver may proceed. However, in some states (such as Utah[54]), if the driver is in a school zone with the lights flashing, the driver must wait until the entire crosswalk is clear before he may proceed.

Massachusetts allows an unusual indication variation for pedestrian movement. At signalized intersections without separate pedestrian signal heads, the traffic signals may be programmed to turn red in all directions, followed by a steady display of yellow lights simultaneously with the red indications. During this red-plus-yellow indication, the intersection is closed to vehicular traffic and pedestrians are given an "exclusive pedestrian interval", or a pedestrian scramble phase, in which they can cross any leg of the intersection, usually in whatever direction they choose.[55] This replaces the extra pedestrian signal, but is in violation of the 2009 MUTCD.[10] This practice is obsolescent but it remains in the Commonwealth's driver's manual.[55]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom and certain parts of the Commonwealth of Nations, animal names are often used to distinguish several types of such crossings. A zebra crossing consists of wide longitudinal stripes on road (perpendicular to the crossing route), with flashing amber Belisha beacons either side of the road. Pedestrians may cross at any time, while drivers must give way to pedestrians on the crossing. A pelican crossing is a signalised pedestrian-operated crossing. The motor traffic facing signals use a flashing amber instead of the conventional red and amber signal of the standard UK traffic signal sequence. A puffin crossing is signalised; however, unlike a pelican crossing which is a timed crossing, The puffin has sensors to detect people still on the crossing. The puffin also uses standard UK traffic signal sequence. A toucan crossing is used by bicycles as well as pedestrians, while a pegasus crossing is used by horse riders - hence having the button to operate the crossing higher up.

Zebra crossings are the only specific pedestrian crossing point that does not use light signals to control traffic movement. The other types of crossing use coloured pictogram lights, depending on the intended users of the crossing this will be a man, a bicycle or a horse.

Mainland Europe

In Spain, Great Britain, Germany and other European countries, 90% of pedestrian fatalities occur outside of pedestrian crossings. The highest rate is in the UK, which has fewer crossings than neighbouring European countries.[56]

Continental crossings do not have the refinements of British ones, but they still indicate a good place to cross.[56]

In Switzerland, zebra crossings are marked in yellow.[57]

In France, it is not mandatory that crosswalks exist. However, if there is one less than 50 meters away, pedestrians are obliged to use it.[58]

- Crosswalk at intersection, in Thun, Switzerland

- Crosswalk at Zurich tramway Central station

Crosswalk before a roundabout, Switzerland

Crosswalk before a roundabout, Switzerland

Some countries in Europe, have used the word pedestrian crossing in some treaties, for instance in the sentence "A vehicle shall not overtake another vehicle which is approaching a pedestrian crossing marked on the carriageway or signposted as such, or which is stopped immediately before the crossing, otherwise than at a speed low enough to enable it to stop immediately if a pedestrian is on the crossing." from the convention on road traffic.[59]

Such convention also consider that

- "pedestrians wishing to cross a carriageway shall not step on to it without exercising care; they shall use a pedestrian crossing whenever there is one nearby;" (§6.a)

- "At other pedestrian crossings, pedestrians shall not step on to the carriageway without taking the distance and speed of approaching vehicles into account." (§6.b iii)

- "to cross the carriageway elsewhere than at a pedestrian crossing signposted as such or indicated by markings on the carriageway, pedestrians shall not step on to the carriageway without first making sure that they can do so without impeding vehicular traffic" (§6.c)

- "Once they have started to cross a carriageway, pedestrians shall not take an unnecessarily long route, and shall not linger or stop on the carriageway unnecessarily." (§6.d).[59]

In Europe, the pedestrian crossing is also dealt with European agreement supplementing the 1968 convention on road traffic done at Geneva on 1 May 1971 (Consolidated version including 1993, 2001, and 2006 amendments):[60]

- "In order to cross the carriageway elsewhere than at a pedestrian crossing signposted as such or indicated by markings on the carriageway, pedestrians shall not step on the carriageway without first making sure that they can do so without impeding vehicular traffic. Pedestrians shall cross the carriageway at right-angles to its axis."

- "The standing or parking of a vehicle shall be prohibited on the carriageway: Within 5 m before pedestrian crossings and crossings for cyclists, on pedestrian crossings, on crossings for cyclists, and on level crossings"

For marking, many European countries are aligned with treaties which states that:

- "To mark pedestrian crossings, relatively broad stripes, parallel to the axis of the carriageway, should preferably be used".[61]

- "To mark cyclist crossings, either transverse lines, or other markings which cannot be confused with those of pedestrian crossings, shall be used."

The convention on road sign also provide warning models for signs and symbol. In those countries, the "pedestrian crossing sign" is on a blue or black ground, with a white or yellow triangle where the symbol is displayed in black or dark blue.[61]

In Europe, the minimum width recommended for pedestrian crossings is 2.5 m (or 8-foot) on roads on which the speed limit is lower than 60 km/h (or 37 mph), and 4 m (or 13-foot) on roads wit a higher or no speed limit.[61]

Australia

In Australia, the terminology pedestrian crossing is used.

Pictograms are standard on all traffic light controlled crossings. Like some other countries, a flashing red sequence is used prior to steady red to clear pedestrians. Moments after, in some instances, a flashing yellow sequence (for motorists) can begin indicating that the vehicles may proceed through the crossing if safe to do so; this is fairly uncommon however. In districts with heavier traffic warranting the use of a traffic light such as inner city areas, the equivalent of the US 'standard' configuration is used.

Zebra crossings are common in low traffic areas and their approaches may be marked by zig zag lines.

Reflector signposting is used at crossings in school zones, however given that most school crossings in the country are manned, these signs only serve as a warning to motorists.

Signals

Pedestrian call buttons

Call buttons are installed at traffic lights with a dedicated pedestrian signal, and are used to bring up the pedestrian "walk" indication in locations where they function correctly.[8][9] In the majority of locations where call buttons are installed, pushing the button does not light up the pedestrian walk sign immediately. One Portland State University researcher notes of call buttons in the US, "Most [call] buttons don’t provide any feedback to the pedestrian that the traffic signal has received the input. It may appear at many locations that nothing happens."[62] However, there are some locations where call buttons do provide confirmation feedback. At such locations, pedestrians are more likely to wait for the "walk" indications.[63]

Reports suggest that many walk buttons in some areas, such as New York City and the United Kingdom, may actually be either placebo buttons or nonworking call buttons that used to function correctly.[8][9] In the former case, these buttons are designed to give pedestrians an illusion of control while the crossing signal continues its operation as programmed.[9] However, in instances of the latter case, such as New York City's, the buttons were simply deactivated when traffic signals were updated to automatically include pedestrian phases as part of every signal cycle. In such instances these buttons may be removed during future updates to the pedestrian signals.[8][64] In the United Kingdom, pressing a button at a standalone pedestrian crossing that is unconnected to a junction will turn a traffic light red immediately, but this is not necessarily the case at a junction.[9]

Sometimes, call buttons work only at some intersections, at certain times of day, or certain periods of the year, such as in New York City or in Boston, Massachusetts.[8][65] In Boston, some busy intersections are programmed to give a pedestrian cycle during certain times of day (so pushing the button is not necessary) but at off-peak times a button push is required to get a pedestrian cycle. In neighboring Cambridge, a button press is always required if a button is available, though the city prefers to build signals where no button is present and the pedestrian cycle always happens between short car cycles.[65] In both cases the light will not turn immediately, but will wait until the next available pedestrian slot in a pre-determined rotation.[65]

Countdown timers

Some pedestrian signals integrate a countdown timer, showing how many seconds are remaining for the clearing phase. In the United States, San Francisco was the first major city to install countdown signals to replace older pedestrian modules, doing so on a trial basis starting in March 2001.[66] The United States MUTCD added a countdown signal as an optional feature to its 2003 edition; if included, the countdown digits would be Portland Orange, the same color as the "Upraised Hand" indication.[46] The MUTCD's 2009 edition changed countdown timers to a mandatory feature on pedestrian signals at all signalized intersections with pedestrian clearance intervals ("flashing upraised hand" phases) longer than seven seconds. With the MUTCD guideline allotting at least one second to cross 3 feet (0.91 m), this indicates that countdown timers are supposed to be installed on roads wider than 21 feet (6.4 m).[10] The countdown is not supposed to be displayed during the pedestrian "walk" interval ("steady walking person" phase),[10]

Some municipalities have found that there are instances where pedestrian countdown signals may be less effective than standard hand/man or "walk"/"dont walk" signals. New York City started studying the pedestrian timers in an inconclusive 2006 study[67] but only started rolling out pedestrian timers on a large scale in 2011 after the conclusion of a second study, which found that pedestrian countdown timers were ineffective at shorter crosswalks.[68] Additionally, a 2000 study of pedestrian countdown timers in Lake Buena Vista, Florida, at several intersections near Walt Disney World, found that pedestrians were more likely to cross the street during the pedestrian clearance interval (flashing upraised hand) if there is a timer present, compared to at intersections where there was no timer present.[69] A study in Toronto found similar results to the Florida study, determining that countdown timers may actually cause more crashes than standard hand/man signals.[70][71] However, other cities such as London found that countdown timers were effective,[72] and New York City found that countdown signals worked mainly at longer crosswalks.[68]

Pedestrian countdown signals are also used elsewhere around the world, such as in Buenos Aires,[73][74] India,[75] Mexico,[76] Taiwan,[77] and the United Arab Emirates.[1] In Mexico City, the walking man moves his feet during the countdown.[76] In Taiwan, all the crossings feature animated men called xiaolüren ("little green man"), who will walk faster immediately before the traffic signal will change. There is also always a countdown timer.[77]

Variations

In some countries, instead of "don't walk", a depiction of a red man or hand indicating when not to cross, the drawing of the person crossing appears with an "X" drawn over it.

Some countries around the Baltic Sea in Scandinavia duplicate the red light. Instead of one red light, there are two which both illuminate at the same time.

In many parts of eastern Germany, particularly the former German Democratic Republic, the design of the crossing man (Ampelmännchen) has a hat. There are also female Ampelmännchen in western Germany and the Netherlands.[76] Other countries also use unusual "walk" and "don't walk" pedestrian indicators. In southwest Yokohama, Kanagawa Prefecture, there are pedestrian signal lights that resemble Astro Boy.[78] In Lisbon, some signals have a "don't walk" indicator that dances; these "dancing man" signals, created by Daimler AG, were created to encourage pedestrians to wait for the "walk" indicator, with the result that 81% more pedestrians stopped and waited for the "walk" light compared to at crosswalks with conventional signals.[79]

Leading Pedestrian Interval

In some areas, the signal timing technique of a Leading Pedestrian Interval (LPI) allows pedestrians exclusive access to a crosswalk, typically 3–7 seconds, before vehicular traffic is permitted.[80][81] Depending on intersection volume and safety history, a normal right-turn-on-red (RTOR) might be explicitly prohibited during the LPI phase.[82] LPI benefits include increased visibility and greater likelihood of vehicles yielding. LPI is among the tools being considered in the fatality-elimination toolkit of Vision Zero planners and advocates.[83]

Temporary signals

In certain circumstances, there are needs to install temporary pedestrian crossing signals. The reasons may include redirecting traffics due to roadworks, closing of the permanent crossing signals due to repairs or upgrades, and establishing new pedestrian crossings for the duration of large public events.

The temporary pedestrian crossings can be integrated into portable traffic signals that may be used during the roadworks, or it can be stand-alone just to stop vehicles to allow pedestrians to safely cross the road without directing vehicle movements. When using the temporary pedestrian crossings signals for roadworks, there should be consideration on signal cycle time. The pedestrian crossing cycles may add longer delay to the traffics which may require additional planning on road work traffic flows.

Depending on the duration and the nature of the temporary signals, the equipment can be installed in different way. One way is to use the permanent traffic signals mounted temporary poles such as poles in concrete-filled barrels. Another way is to use portable pedestrian crossing signals.[84]

Enhancements for disabled people

Pedestrian controlled crossings are sometimes provided with enhanced features to assist disabled people.

Tactile indications

Tactile cones near or under the control button may rotate or shake when the pedestrian signal is in the pedestrian "walk" phase. This is for pedestrians with visual impairments. A vibrating button is used in Australia, Germany, some parts of the United States, Greece, Ireland, and Hong Kong to assist hearing-impaired people. Alternatively, electrostatic, touch-sensitive buttons require no force to activate. To confirm that a request has been registered, the buttons usually emit a chirp or other sound. They also offer anti-vandalism benefits due to not including moving parts which are sometimes jammed on traditional push-button units.

Tactile surfacing patterns (or tactile pavings) may be laid flush within the adjacent footways (US: sidewalks), so that visually impaired pedestrians can locate the control box and cone device and know when they have reached the other side. In Britain, different colours of tactile paving indicate different types of crossings; yellow (referred to as buff coloured) is used at non-controlled (no signals) crossings, and red is used at controlled (signalised) locations.[10]

Audible signals

Crosswalks have adaptations, mainly for people with visual impairments, through the addition of accessible pedestrian signals (APS) that may include speakers at the pushbutton, or under the signal display, for each crossing location.[85] These types of signals have been shown to reduce conflicts between pedestrians and vehicles.[86] However, without other indications such as tactile pavings or cones, these APS units may be hard for visually impaired people to locate.[87]

In the United States, the standards in the 2009 MUTCD require APS units to have a pushbutton locator tone, audible and vibrotactile walk indications, a tactile arrow aligned with the direction of travel on the crosswalk, and to respond to ambient sound. The pushbutton locator tone is a beep or tick, repeating at once per second, to allow people who are blind to find the device.[10] If APS units are installed in more than one crossing direction (e.g. if there are APS units at a curb for both the north–south and west–east crossing directions), different sounds or speech messages may be used for each direction.[85] Under the MUTCD guideline, the walk indication may be a speech message if two or more units on the same curb are separated by less than 10 feet (3.0 m). These speech messages usually follow the pattern "[Street name]. Walk sign is on to cross [Street Name]."[88] Otherwise, the walk indication may be a "percussive tone," which usually consists of repeated, rapid sounds that can be clearly heard from the opposite curb and can oscillate between high and low volumes.[88] In both cases, when the "don't walk" indication is flashing, the device will beep at every second until the "don't walk" indication becomes steady and the pedestrian countdown indication reaches "0", at which point the device will beep intermittently at lower volume.[88] When activated, the APS units are mandated to be accompanied by a vibrating arrow on the APS during the walk signal.[10]

The devices have been in existence since the mid-20th century, but were not popular until the 2000s because of concerns over noise.[85] As of the 2009 MUTCD, APS are supposed to be set to be heard only 6 to 12 feet from the device to be easy to detect from a close distance but not so loud as to be intrusive to neighboring properties.[10] Among American cities, San Francisco has one of the greatest numbers of APS-equipped intersections in the United States, with APS installed at 202 intersections as of October 2016.[89] New York City has APS at 131 intersections as of November 2015, with 75 more intersections to be equipped every year after that.[90]

APS in other countries may consist of a short recorded message, as in Scotland, Hong Kong, Singapore and some parts of Canada (moderate to large urban centres). In Japan, various electronic melodies are played, often of traditional melancholic folk songs such as "Tōryanse" or "Sakura". In Croatia, Denmark and Sweden, beeps (or clicks) with long intervals in-between signifying "don't walk" mode and beeps with very short intervals signifying "walk" mode.

Relief symbol

On some pushbutton especially in Austria and Germany there is a symbolic relief showing the crossing situation for the visually impaired, so they can get an overview of the crossing.

The relief is read from the bottom up. It consists of different modules, which are put together according to the crosswalk. Each pedestrian crossing begins with the start symbol, consisting of an arrow and a broad line representing the curb. Subsequently, different modules for traffic lanes and islands follow. The relief is completed with a broad line.

Modules for traffic lanes consist of a dash in the middle and a symbol for the kind of lane right or left of the dash, depending on the direction from which the traffic crosses the crossing. If a crossing is possible from both directions, a symbol is located on both sides. If the pedestrian crossing is a zebra crossing, the middle line is dashed. A traffic light secured crossing has a solid line.

A cycle path is represented by two points next to each other, a vehicle lane by a rectangle and tram rails by two lines lying one above the other.

Islands are represented as a rectangle, which has semicircles on the right and left side. If there is a pushbutton for pedestrians on the island, there is a dot in the middle of the rectangle. If the pedestrian walkway divides on an island, the rectangle may be open on the right or left side.[91]

| Symbol | securing | typ | direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| End | |||

| zebra crossing | cycle path | bidirectional | |

| zebra crossing | cycle path | right | |

| zebra crossing | vehicle lane | right | |

| zebra crossing | tram tracks | right | |

| island with pushbutton | open to the left | ||

| island with pushbutton | |||

| island | |||

| traffic light | tram tracks | left | |

| traffic light | vehicle lane | left | |

| traffic light | cycle path | left | |

| traffic lights | cycle path | bidirectional | |

| Start |

Key-based system

In Perth, Western Australia, an extended phase system called "Keywalk" was developed by the Main Roads Department of Western Australia in response to concerns from disability advocates about the widening of the Albany Highway in that city in the mid-1990s. The Department felt that extending the walk phase permanently on cross streets would cause too much disruption to traffic flow on the highway and so the Keywalk system was developed to allow for those who needed an extended green light phase to cross the road safely. A small electronic key adjusted the green/walk and flashing red/complete crossing phases to allow more time for the key holder to complete the crossing of the highway safely. The system was first installed at the junction of Albany Highway and Cecil Avenue.[92] It is unclear what became of this system.

Lighting

There are two types of crosswalk lights: those that illuminate the whole crosswalk area, and warning lights.[93]

The Illuminating Engineering Society of North America currently provides engineering design standards for highway lighting. In the US, in conventional intersections, area lighting is typically provided by pole-mounted luminaires.[94] These systems illuminate the crosswalk as well as surrounding areas, and do not always provide enough contrast between the pedestrian and his or her background.

There have been many efforts to create lighting scenarios that offer better nighttime illumination in crosswalks. Some innovative concepts include:

Illuminating lights

- Bollard posts containing linear light sources inside. These posts have been shown to sufficiently illuminate the pedestrian but not the background, consequently increasing contrast and improving pedestrian visibility and detection.[95] Although this method shows promise in being incorporated into crosswalk lighting standards, more studies need to be done.[96][97]

- Festooned strings of light over the top of the crosswalk.[98]

Warning lights

- In-pavement lighting oriented to face oncoming traffic.[99]

- In-pavement, flashing warning lights oriented upwards (especially visible to children, the short-statured, and smombies)[100][101]

- Pole-mounted, flashing warning lights (mounted similar to a traffic signal).

- Pedestrian warning signs enhanced with LED lights either within the sign face[102] or underneath it.[103][104]

In areas with heavy snowfall, using in-pavement lighting can be problematic, since snow can obscure the lights, and snowplows can damage them.

Railway pedestrian crossings

In Finland, fences in the footpath approaching the crossing force pedestrians and bicycles to slow down to navigate a zigzag path, which also tends to force that user to look out for the train.

Pedestrian crossings across railways may be arranged differently elsewhere, such as in New South Wales, where they consist of:

- a barrier which closes when a train approaches;

- a "Red Man" light; no light when no train approaching

- an alarm

In France, when a train is approaching, a red man is shown with the word STOP flashing in red (R25 signal).[105]

When a footpath crosses a railway in the United Kingdom, there will most often be gates or stiles protecting the crossing from wildlife and livestock. In situations where there is little visibility along the railway, or the footpath is especially busy, there will also be a small set of lights with an explanatory sign. When a train approaches, the signal light will change to red and an alarm will sound until the train has cleared the crossing.

Safety

The safety of unsignalled pedestrian or zebra crossings is somewhat contested in traffic engineering circles.

Research undertaken in New Zealand showed that a zebra crossing without other safety features on average increases pedestrian crashes by 28% compared to a location without crossings. However, if combined with (placed on top of) a speed table, zebra crossings were found to reduce pedestrian crashes by 80%.[106]

A five-year U.S. study of 1,000 marked crosswalks and 1,000 unmarked comparison sites found that on most roads, the difference in safety performance of marked and unmarked crossings is not statistically significant, unless additional safety features are used. On multilane roads carrying over 12,000 vehicles per day, a marked crosswalk is likely to have worse safety performance than an otherwise similar unmarked location, unless safety features such as raised median refuges or pedestrian beacons are also installed.[107] On multilane roads carrying over 15,000 vehicles per day, a marked crosswalk is likely to have worse safety performance than an unmarked location, even if raised median refuges are provided. The marking pattern had no significant effect on safety. This study only included locations where vehicle traffic was not controlled by a signal or stop sign.[107]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pedestrian crossings. |

- Footpath

- Stile

- Traffic light

- The Greenwalking

- Road surface marking

References

- "Abu Dhabi installs countdown signal system for pedestrians". GulfNews. 6 February 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Bradley, Pamela (23 May 2013). Cities of Vesuvius: Pompeii and Herculaneum. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107638112.

- Muhammad M. Ishaque; Robert B. Noland. "Making Roads Safe for Pedestrians or Keeping them Out of the Way? - an Historical Perspective on Pedestrian Policies in Britain" (PDF). Imperial College London Centre for Transport Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- The Times, 14 Feb. 1911, pg. 14: The Pedestrian's Chances.

- https://www.nevadadot.com/home/showdocument?id=9057

- "Right of Way in the Crosswalk" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2014.

- "Your guide to PEDESTRIAN CROSSINGS" (PDF). Trafford Council. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- "Chapter 4E - MUTCD 2009 Edition". FHWA. 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- "Death by Car". NYMag.com. December 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- Jaffe, Eric (18 December 2012). "A Brief History of the Barnes Dance". CityLab. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- Wetmore, John (29 October 2012). "Perils For Pedestrians". Pedestrian Bridges. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- National Association of City Transportation Officials; Global Designing Cities Initiative (2016). Global Street Design Guide. Island Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-61091-702-5. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- Fisher, Donald L.; Rizzo, Matthew; Caird, Jeffrey; Lee, John D. (2011). Handbook of Driving Simulation for Engineering, Medicine, and Psychology. CRC Press. p. 34–PA10. ISBN 978-1-4200-6101-7. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- "Guide for Maintaining Pedestrian Facilities for Enhanced Safety Research Report - Safety". Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- Perry, Francesca (14 July 2016). "Creative crosswalks around the world – in pictures". the Guardian. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- Metcalfe, John (25 February 2014). "How to Make Crosswalks Artistically Delightful". CityLab. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- Jacobson, Willis (21 August 2015). "'Creative Crossings' organizers unveil crosswalk artwork". Lompoc Record. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- Jacobson, Willis (22 April 2016). "Second set of Lompoc crosswalks undergoes artistic makeover". Lompoc Record. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- "Tbilisi opening up for colorful crosswalks". GeorgianJournal. 31 January 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- "Colorful 3D zebra crossing seen in China's Changsha". Xinhua. 29 January 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- "Ten More Creative Crosswalks & Zany Zebra Crossings". WebUrbanist. 27 May 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- "Love zebra crossing in Chengdu". Xinhua. 3 February 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- Bechtel, Allyson K.; MacLeod, Kara E.; Ragland, David R. (17 December 2003). "Oakland Chinatown Pedestrian Scramble: An Evaluation". Safe Transportation Research & Education Center. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- Branson-Potts, Hailey (14 March 2014). "San Francisco's Castro District to get gay pride rainbow crosswalks". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- "West Hollywood's rainbow-colored crosswalks to stay". Los Angeles Times. 27 August 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- "Crews Paint Rainbow Crosswalks in Center City". CBS Philly. 25 June 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- Lior, Ilan (16 May 2012). "Tel Aviv's rainbow crosswalk draws cheers, then jeers, online". haaretz.com. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- "Long Beach Tunes Up Road Safety With Painted Piano Crosswalks". NBC Southern California. 30 September 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- Rueb, Emily S. (7 October 2019). "The Government Says Rainbow Crosswalks Could Be Unsafe. Are They Really?". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- Lee, Jessica (6 August 2015). "Crosswalks marked with colors of Pan-African flag". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- "Part II of II: Best Practices Design Guide - Sidewalk2 - Publications - Bicycle and Pedestrian Program - Environment - FHWA". www.fhwa.dot.gov. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "Chapter 3B - MUTCD 2009 Edition". FHWA. 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "Chapter 4F - MUTCD 2009 Edition". FHWA. 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- See here (discussing the Uniform Vehicle Code and stating that "a crosswalk at an intersection is defined as the extension of the sidewalk or the shoulder across the intersection, regardless of whether it is marked or not."); see also California Vehicle Code section 275(a) ("'Crosswalk' is . . . [t]hat portion of a roadway included within the [extension] of the boundary lines of sidewalks at intersections where the intersecting roadways meet at approximately right angles, except the [extension] of such lines from an alley across a street")

- "What is the new crosswalk law in Ontario and what's the reason for it?". The Globe and Mail. 26 January 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "2000 MUTCD - PART 4 - TRAFFIC SIGNALS" (PDF). fhwa.dot.gov. December 2000. pp. 4E1 to 4E14. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- "Driver's Handbook".

- Smallwood, Karl (21 July 2014). "Why No One Bothers Putting Apostrophes in "Don't Walk" Signs". Gizmodo. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- Yauch, Peter J. (1 January 1990). Traffic Signal Control Equipment: State of the Art. Transportation Research Board. p. 43. ISBN 9780309049177.

- "Figure 4E-2 Long Description - MUTCD 2009 Edition". FHWA. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Houten, Ron; Retting, Richard; Farmer, Charles; Houten, Joy (1 January 2000). "Field Evaluation of a Leading Pedestrian Interval Signal Phase at Three Urban Intersections". Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board. 1734: 86–92. doi:10.3141/1734-13. ISSN 0361-1981.

- Olson, P.L.; Dewar, R.E. (2002). Human Factors in Traffic Safety. Lawyers & Judges Pub. ISBN 978-0-913875-47-6. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- Raschke, Kurt (12 November 2010). "'Walking person' confusion". Kurt Raschke – Technologist. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- "FHWA - MUTCD - 2003 Edition Chapter 4E". mutcd.fhwa.dot.gov. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Redmon, Tamara. "Looking Out for Pedestrians - Looking Out for Pedestrians, November/December 2005 - FHWA-HRT-05-001 Vol. 69 No. 3". Home | Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- Van Houten, R. (2001). "ANIMATED LED "EYES" TRAFFIC SIGNALS" (PDF). ITS-IDEA Program Project Final Report.

- "History of Traffic Signal Visors". www.kbrhorse.net. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "Pedestrian Signals". www.signalfan.com. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "Automated Pedestrian Detection". Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- Hughes, R.; Huang, H.; Zegeer, C.; Cynecki, M. (2001). "EVALUATION OF AUTOMATED PEDESTRIAN DETECTION AT SIGNALIZED INTERSECTIONS" (PDF). Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2006. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- Mead, Jill; Zegeer, Charlie; Bushell, Max (April 2014). "Evaluation of Pedestrian-Related Roadway Measures: A Summary of Available Research" (PDF). Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center.

- "Title 41 Chapter 6a Part 10 Section 1002". Utah State Legislature. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- Massachusetts Department of Transportation, Registry of Motor Vehicles Division (c. 2015). Driver's Manual (PDF). p. 82.

You must yield to pedestrians if your traffic signal is red or if it is red and yellow.

- "Public Affairs : AA pedestrian crossings survey in Europe - the AA".

- https://www.polisnetwork.eu/uploads/Modules/PublicDocuments/pedestrian_crossings_intro.pdf

- Code de la route, article R412-37

- http://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/trans/conventn/Conv_road_traffic_EN.pdf

- "UNECE Homepage". www.unece.org. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- http://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/trans/conventn/Conv_road_signs_2006v_EN.pdf

- Gan, Vicky (2 September 2015). "Ask CityLab: Do "WALK" Buttons Actually Do Anything?". CityLab. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Van Houten, Ron; Ellis, Ralph; Sanda, Jose; Kim, Jin-Lee (2006). "Pedestrian Push-Button Confirmation Increases Call Button Usage and Compliance". Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board. 1982: 99–103. doi:10.3141/1982-14.

- Kim, Susanna (31 July 2014). "Why the Crosswalk Buttons in Your City May Not Work". ABC News. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Ragusea, Adam (10 May 2010). "Crosswalk Buttons Don't Do Anything! Except When They Do". Radio Boston.

- "Pedestrian Countdown Signals: Experience with an Extensive Pilot Installation" (PDF). ITE Journal. January 2006. pp. 43–48. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Chan, Sewell (3 November 2006). "Too Slow in the Crosswalk? Automatic Timers Will Tell You". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- "Countdown Clocks Coming to City Crosswalks". NBC New York. 16 August 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Huang, Herman; Zegeer, Charles (November 2000). "The Effects of Pedestrian Countdown Signals in Lake Buena Vista" (PDF). fdot.gov. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Highway Safety Research Center. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Kapoor, Sacha; Magesan, Arvind. "Paging Inspector Sands: The Costs of Public Information" (PDF). people.few.eur.nl. Erasmus School of Economics. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Richmond, Sarah A; Willan, Andrew R; Rothman, Linda; Camden, Andi; Buliung, Ron; Macarthur, Colin; Howard, Andrew (9 March 2017). "The impact of pedestrian countdown signals on pedestrian-motor vehicle collisions: a reanalysis of data from a quasi-experimental study". Injury Prevention. 20 (3): 155–158. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2012-040717. ISSN 1353-8047. PMC 4033273. PMID 24065777.

- "Pedestrian Countdown at Traffic Signals - An overview of London's successful trials" (PDF). Transport for London. September 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- "Podrán programar semáforos según el estado del tránsito". Clarín (in Spanish). 19 November 2010. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- "Patente de Invención, Semáforo vehicular-peatonal con aviso de cambio en unidad de tiempo". Instituto Nacional de la Propiedad Industrial (in Spanish). INPI. 28 November 2006. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- Biswas, Sabyasachi; Ghosh, Indrajit; Chandra, Satish (1 April 2017). "Effect of Traffic Signal Countdown Timers on Pedestrian Crossings at Signalized Intersection". Transportation in Developing Economies. 3 (1): 2. doi:10.1007/s40890-016-0032-7. ISSN 2199-9287.

- Walker, Alissa. "7 Crosswalk Signals You Won't Mind Waiting For". Gizmodo. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Long, Kejun; Han, Lee D.; Yang, Qiang (1 October 2011). "Effects of countdown timers on driver behavior after the yellow onset at Chinese intersections". Traffic Injury Prevention. 12 (5): 538–544. doi:10.1080/15389588.2011.593010. ISSN 1538-957X. PMID 21972865.

- Metcalfe, John (19 November 2014). "Japan Now Has a Traffic Signal Shaped Like Astro Boy". CityLab. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- Liszewski, Andrew (16 September 2014). "Waiting for 'Don't Walk' Signs Is More Fun When the Stick Figure Dances". Gizmodo. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "Leading Pedestrian Interval". National Association of City Transportation Officials. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- "Proven Safety Countermeasures - Leading Pedestrian Intervals - Safety | Federal Highway Administration". safety.fhwa.dot.gov. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- "Right Turn on Red Restrictions". safety.fhwa.dot.gov. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- Bliss, Laura (26 January 2018). "The Best Cheap Street Fix". CityLab. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- "Signal-Controlled Pedestrian Facilities at Portable Traffic Signals" (PDF). Department for Transport (United Kingdom) (Traffic Advisory Leaflet). June 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- Bentzen, Billie Louise; Tabor, Lee S. (August 1998). "Accessible Pedestrian Signals" (PDF). Accessible Design for the Blind. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- Van Houten, Ron; Louis Malenfant, J.; Van Houten, Joy; Retting, Richard (1 January 1997). "Using Auditory Pedestrian Signals To Reduce Pedestrian and Vehicle Conflicts". Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board. 1578: 20–22. doi:10.3141/1578-03. ISSN 0361-1981.

- Barlow, Janet M.; Scott, Alan C.; Bentzen, Billie Louise (1 January 2009). "Audible Beaconing with Accessible Pedestrian Signals". AER Journal : Research and Practice in Visual Impairment and Blindness. 2 (4): 149–158. ISSN 1945-5569. PMC 2901122. PMID 20622978.

- "APS Technical Specifications" (PDF). SFMTA. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- "Accessible Pedestrian Signals (APS), October 31, 2016" (PDF). SFMTA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- "Accessible Pedestrian Signals Program Status Report" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of Transportation. November 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- "Productinformation Signal requesting device (EK 533)" (PDF). Langmatz GmbH. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- Keywalk for the disabled is an Australian first (March 1995). Western Roads: official journal of Main Roads, Western Australia, 18(4), p.10. Perth: Main Roads Department.

- Illuminating Engineering Society of North America. American National Standard Practice for Roadway Lighting. Publication IESNA-RP-8-00. Illuminating Engineering Society of North America, New York, 2000.

- Hasson, P., P. Lutkevich, B. Ananthanarayanan, P. Watson, and R. Knoblauch. Field Test for Lighting to Improve Safety at Pedestrian Crosswalks. Presented at the 16th Biennial Transportation Research Board Visibility Symposium, Iowa City, Ia., 2002.

- "Crosswalk Demonstration Project: Design and Evaluation of Effective Crosswalk Illumination - University Transportation Research Center" (PDF).

- "Press Releases - LRC Newsroom". Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Bullough, J.D., X. Zhang, N.P. Skinner, and M.S. Rea. Design and Evaluation of Effective Crosswalk Lighting. Publication FHWA-NJ-2009-03. New Jersey Department of Transportation, Trenton, NJ, 2009.

- "Illuminated Air Crosswalk Concept".

- "Pedestrian & Bicycle Information Center". Archived from the original on 2 December 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- "German traffic light for smartphone zombies", The Guardian, 29 April 2016

- "Crosswalk Lights, Pedestrian Crossing Signs - Traffic Safety Corp".

- Embedded LEDs in Signs, Federal highway Administration, May 2009

- Van Houten, Ron and & Malenfant, J.E. Louis, Efficacy of Rectangular-shaped Rapid Flash LED Beacons, Retrieved 25 March 2011

- Impacts of LED Brightness, Flash Pattern, and Location for Illuminated Pedestrian Traffic Control Device, Federal Highway Administration, May 2015

- Sécurisation des traversées piétonnes des voies de tramway, CETE Sud-Ouest

- Pedestrian planning and design guide. Land Transport New Zealand / NZ Transport Agency. 2007. ISBN 978-0-478-30945-4.

- Zegeer, Charles (2002). Safety Effects of Marked vs. Unmarked Crosswalks at Uncontrolled Locations:Executive Summary and Recommended Guidelines (PDF). Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

External links

- Bicycle and Pedestrian Statistics Federal Highway Administration (US)

- The Design of Pedestrian Crossings - Department for Transport (United Kingdom)

- Photos of pedestrian signals from various countries

- Investigating Improvements to Pedestrian Crossings FHWA.dot.gov