Network theory

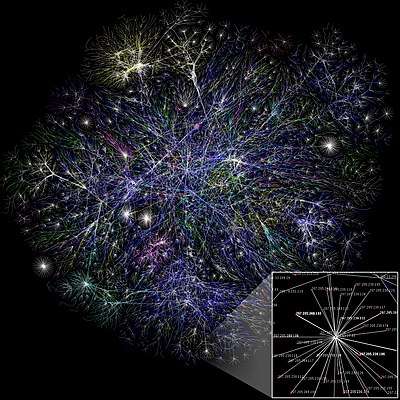

Network theory is the study of graphs as a representation of either symmetric relations or asymmetric relations between discrete objects. In computer science and network science, network theory is a part of graph theory: a network can be defined as a graph in which nodes and/or edges have attributes (e.g. names).

| Network science | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network types | ||||

| Graphs | ||||

|

||||

| Models | ||||

|

||||

| ||||

|

||||

Network theory has applications in many disciplines including statistical physics, particle physics, computer science, electrical engineering[1][2], biology,[3] economics, finance, operations research, climatology, ecology, public health,[4][5] and sociology. Applications of network theory include logistical networks, the World Wide Web, Internet, gene regulatory networks, metabolic networks, social networks, epistemological networks, etc.; see List of network theory topics for more examples.

Euler's solution of the Seven Bridges of Königsberg problem is considered to be the first true proof in the theory of networks.

Network optimization

Network problems that involve finding an optimal way of doing something are studied under the name combinatorial optimization. Examples include network flow, shortest path problem, transport problem, transshipment problem, location problem, matching problem, assignment problem, packing problem, routing problem, critical path analysis and PERT (Program Evaluation & Review Technique). In order to break a NP-hard task of network optimization down into subtasks the network is decomposed into relatively independent subnets.[6]

Network analysis

Electric network analysis

The electric power systems analysis could be conducted using network theory from two main points of view:

(1) an abstract perspective (i.e., as a graph consists from nodes and edges), regardless of the electric power aspects (e.g., transmission line impedances). Most of these studies focus only on the abstract structure of the power grid using node degree distribution and betweenness distribution, which introduces substantial insight regarding the vulnerability assessment of the grid. Through these types of studies, the category of the grid structure could be identified from the complex network perspective (e.g., single-scale, scale-free). This classification might help the electric power system engineers in the planning stage or while upgrading the infrastructure (e.g., add a new transmission line) to maintain a proper redundancy level in the transmission system.[7]

(2) weighted graphs that blend an abstract understanding of complex network theories and electric power systems properties.[8]

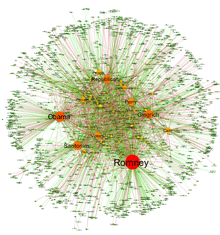

Social network analysis

Social network analysis examines the structure of relationships between social entities.[10] These entities are often persons, but may also be groups, organizations, nation states, web sites, or scholarly publications.

Since the 1970s, the empirical study of networks has played a central role in social science, and many of the mathematical and statistical tools used for studying networks have been first developed in sociology.[11] Amongst many other applications, social network analysis has been used to understand the diffusion of innovations, news and rumors. Similarly, it has been used to examine the spread of both diseases and health-related behaviors. It has also been applied to the study of markets, where it has been used to examine the role of trust in exchange relationships and of social mechanisms in setting prices. Similarly, it has been used to study recruitment into political movements and social organizations. It has also been used to conceptualize scientific disagreements as well as academic prestige. More recently, network analysis (and its close cousin traffic analysis) has gained a significant use in military intelligence, for uncovering insurgent networks of both hierarchical and leaderless nature.

Biological network analysis

With the recent explosion of publicly available high throughput biological data, the analysis of molecular networks has gained significant interest.[12] The type of analysis in this context is closely related to social network analysis, but often focusing on local patterns in the network. For example, network motifs are small subgraphs that are over-represented in the network. Similarly, activity motifs are patterns in the attributes of nodes and edges in the network that are over-represented given the network structure. Using networks to analyse patterns in biological systems, such as food-webs, allows us to visualize the nature and strength of interactions between species. The analysis of biological networks with respect to diseases has led to the development of the field of network medicine.[13] Recent examples of application of network theory in biology include applications to understanding the cell cycle[14] as well as a quantitative framework for developmental processes.[15] The interactions between physiological systems like brain, heart, eyes, etc. can be regarded as a physiological network.[16]

Narrative network analysis

The automatic parsing of textual corpora has enabled the extraction of actors and their relational networks on a vast scale. The resulting narrative networks, which can contain thousands of nodes, are then analysed by using tools from Network theory to identify the key actors, the key communities or parties, and general properties such as robustness or structural stability of the overall network, or centrality of certain nodes.[18] This automates the approach introduced by Quantitative Narrative Analysis,[19] whereby subject-verb-object triplets are identified with pairs of actors linked by an action, or pairs formed by actor-object.[17]

Link analysis

Link analysis is a subset of network analysis, exploring associations between objects. An example may be examining the addresses of suspects and victims, the telephone numbers they have dialed and financial transactions that they have partaken in during a given timeframe, and the familial relationships between these subjects as a part of police investigation. Link analysis here provides the crucial relationships and associations between very many objects of different types that are not apparent from isolated pieces of information. Computer-assisted or fully automatic computer-based link analysis is increasingly employed by banks and insurance agencies in fraud detection, by telecommunication operators in telecommunication network analysis, by medical sector in epidemiology and pharmacology, in law enforcement investigations, by search engines for relevance rating (and conversely by the spammers for spamdexing and by business owners for search engine optimization), and everywhere else where relationships between many objects have to be analyzed. Links are also derived from similarity of time behavior in both nodes. Examples include climate networks where the links between two locations (nodes) are determined for example, by the similarity of the rainfall or temperature fluctuations in both sites.[20][21][22]

Network robustness

The structural robustness of networks is studied using percolation theory.[23] When a critical fraction of nodes (or links) is removed randomly (random failures), the network becomes fragmented into small disconnected clusters. This phenomenon is called percolation,[24] and it represents an order-disorder type of phase transition with critical exponents. Percolation theory can predict the size of the largest component (called giant component), the critical percolation threshold and the critical exponents. The failures discussed above are random, as usually assumed in percolation theory. However, when generalizing percolation also to non-random but targeted attacks, e.g., on highest degree nodes, the results, such as p_c, change significantly[25][26] .Recently, a new type of failures in networks has been developed, called localized attacks.[27] In this case one choses randomly a node and remove its neighbors and next nearest neighbors until a fraction of 1-p nodes are removed. One such realistic example of random percolation is the use of percolation theory to predict the fragmentation of biological virus shells (capsids), with the percolation threshold of Hepatitis B Virus capsid predicted and detected experimentally: a molecular, randomly played game of Jenga on a rhombically tiled sphere. [28] [29]

Web link analysis

Several Web search ranking algorithms use link-based centrality metrics, including Google's PageRank, Kleinberg's HITS algorithm, the CheiRank and TrustRank algorithms. Link analysis is also conducted in information science and communication science in order to understand and extract information from the structure of collections of web pages. For example, the analysis might be of the interlinking between politicians' web sites or blogs. Another use is for classifying pages according to their mention in other pages.[30]

Centrality measures

Information about the relative importance of nodes and edges in a graph can be obtained through centrality measures, widely used in disciplines like sociology. For example, eigenvector centrality uses the eigenvectors of the adjacency matrix corresponding to a network, to determine nodes that tend to be frequently visited. Formally established measures of centrality are degree centrality, closeness centrality, betweenness centrality, eigenvector centrality, subgraph centrality and Katz centrality. The purpose or objective of analysis generally determines the type of centrality measure to be used. For example, if one is interested in dynamics on networks or the robustness of a network to node/link removal, often the dynamical importance[31] of a node is the most relevant centrality measure. For a centrality measure based on k-core analysis see ref.[32]

Assortative and disassortative mixing

These concepts are used to characterize the linking preferences of hubs in a network. Hubs are nodes which have a large number of links. Some hubs tend to link to other hubs while others avoid connecting to hubs and prefer to connect to nodes with low connectivity. We say a hub is assortative when it tends to connect to other hubs. A disassortative hub avoids connecting to other hubs. If hubs have connections with the expected random probabilities, they are said to be neutral. There are three methods to quantify degree correlations.

Recurrence networks

The recurrence matrix of a recurrence plot can be considered as the adjacency matrix of an undirected and unweighted network. This allows for the analysis of time series by network measures. Applications range from detection of regime changes over characterizing dynamics to synchronization analysis.[33][34][35]

Spread

Content in a complex network can spread via two major methods: conserved spread and non-conserved spread.[36] In conserved spread, the total amount of content that enters a complex network remains constant as it passes through. The model of conserved spread can best be represented by a pitcher containing a fixed amount of water being poured into a series of funnels connected by tubes . Here, the pitcher represents the original source and the water is the content being spread. The funnels and connecting tubing represent the nodes and the connections between nodes, respectively. As the water passes from one funnel into another, the water disappears instantly from the funnel that was previously exposed to the water. In non-conserved spread, the amount of content changes as it enters and passes through a complex network. The model of non-conserved spread can best be represented by a continuously running faucet running through a series of funnels connected by tubes. Here, the amount of water from the original source is infinite. Also, any funnels that have been exposed to the water continue to experience the water even as it passes into successive funnels. The non-conserved model is the most suitable for explaining the transmission of most infectious diseases, neural excitation, information and rumors, etc.

Network Immunization

The question of how to immunize efficiently scale free networks which represent realistic networks such as the Internet and social networks has been studied extensively. One such strategy is to immunize the largest degree nodes, i.e., targeted (intentional) attacks^[24a,24b] since for this case p_c is relatively high and less nodes are needed to be immunized. However, in most realistic nodes the global structure is not available and the largest degree nodes are not known. For this case the method of acquaintance immunization has been developed [37]. In this case, which is quite efficient one choses randomly nodes but immunize their neighbors. Another and even more efficient method is based on graph parition method [38].

Interdependent networks

An interdependent network is a system of coupled networks where nodes of one or more networks depend on nodes in other networks. Such dependencies are enhanced by the developments in modern technology. Dependencies may lead to cascading failures between the networks and a relatively small failure can lead to a catastrophic breakdown of the system. Blackouts are a fascinating demonstration of the important role played by the dependencies between networks. A recent study developed a framework to study the cascading failures in an interdependent networks system.[39][40]

See also

- Complex network

- Congestion game

- Quantum complex network

- Dual-phase evolution

- Percolation theory

- Network partition

- Percolation theory

- Network science

- Network theory in risk assessment

- Network topology

- Network analyzer

- Seven Bridges of Königsberg

- Small-world networks

- Social network

- Scale-free networks

- Network dynamics

- Sequential dynamical systems

- Pathfinder networks

- Human disease network

- Biological network

- Network medicine

References

- Saleh, Mahmoud; Esa, Yusef; Mohamed, Ahmed (2018-05-29). "Applications of Complex Network Analysis in Electric Power Systems". Energies. 11 (6): 1381. doi:10.3390/en11061381.

- Saleh, Mahmoud; Esa, Yusef; Onuorah, Nwabueze; Mohamed, Ahmed A. (2017). "Optimal microgrids placement in electric distribution systems using complex network framework". Optimal microgrids placement in electric distribution systems using complex network framework - IEEE Conference Publication. ieeexplore.ieee.org. pp. 1036–1040. doi:10.1109/ICRERA.2017.8191215. ISBN 978-1-5386-2095-3. Retrieved 2018-06-07.

- Habibi, Iman; Emamian, Effat S.; Abdi, Ali (2014-01-01). "Quantitative analysis of intracellular communication and signaling errors in signaling networks". BMC Systems Biology. 8: 89. doi:10.1186/s12918-014-0089-z. ISSN 1752-0509. PMC 4255782. PMID 25115405.

- Harris, Jenine K; Luke, Douglas A; Zuckerman, Rachael B; Shelton, Sarah C (2009). "Forty Years of Secondhand Smoke Research: The Gap Between Discovery and Delivery". AMEPRE American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 36 (6): 538–548. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.039. ISSN 0749-3797. OCLC 5899755895. PMID 19372026.

- Varda, Danielle M; Forgette, Rich; Banks, David; Contractor, Noshir (2009). "Social Network Methodology in the Study of Disasters: Issues and Insights Prompted by Post-Katrina Research". Popul Res Policy Rev Population Research and Policy Review : In Cooperation with the Southern Demographic Association (SDA). 28 (1): 11–29. doi:10.1007/s11113-008-9110-9. ISSN 0167-5923. OCLC 5659930640.

- Ignatov, D.Yu.; Filippov, A.N.; Ignatov, A.D.; Zhang, X. (2016). "Automatic Analysis, Decomposition and Parallel Optimization of Large Homogeneous Networks". Proc. ISP RAS. 28 (6): 141–152. arXiv:1701.06595. doi:10.15514/ISPRAS-2016-28(6)-10.

- Saleh, Mahmoud; Esa, Yusef; Mohamed, Ahmed (2018-05-29). "Applications of Complex Network Analysis in Electric Power Systems". Energies. 11 (6): 1381. doi:10.3390/en11061381.

- Saleh, Mahmoud; Esa, Yusef; Onuorah, Nwabueze; Mohamed, Ahmed A. (2017). "Optimal microgrids placement in electric distribution systems using complex network framework". Optimal microgrids placement in electric distribution systems using complex network framework - IEEE Conference Publication. ieeexplore.ieee.org. pp. 1036–1040. doi:10.1109/ICRERA.2017.8191215. ISBN 978-1-5386-2095-3. Retrieved 2018-06-07.

- Grandjean, Martin (2014). "La connaissance est un réseau". Les Cahiers du Numérique. 10 (3): 37–54. doi:10.3166/lcn.10.3.37-54. Retrieved 2014-10-15.

- Wasserman, Stanley and Katherine Faust. 1994. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Rainie, Lee and Barry Wellman, Networked: The New Social Operating System. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012.

- Newman, M.E.J. Networks: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. 2010

- Habibi, Iman; Emamian, Effat S.; Abdi, Ali (2014-10-07). "Advanced Fault Diagnosis Methods in Molecular Networks". PLOS One. 9 (10): e108830. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j8830H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0108830. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4188586. PMID 25290670.

- Barabási, A. L.; Gulbahce, N.; Loscalzo, J. (2011). "Network medicine: a network-based approach to human disease". Nature Reviews Genetics. 12 (1): 56–68. doi:10.1038/nrg2918. PMC 3140052. PMID 21164525.

- Jailkhani, N.; Ravichandran, N.; Hegde, S. R.; Siddiqui, Z.; Mande, S. C.; Rao, K. V. (2011). "Delineation of key regulatory elements identifies points of vulnerability in the mitogen-activated signaling network". Genome Research. 21 (12): 2067–81. doi:10.1101/gr.116145.110. PMC 3227097. PMID 21865350.

- Jackson M, Duran-Nebreda S, Bassel G (October 2017). "Network-based approaches to quantify multicellular development". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 14 (135): 20170484. doi:10.1098/rsif.2017.0484. PMC 5665831. PMID 29021161.

- Bashan, Amir; Bartsch, Ronny P.; Kantelhardt, Jan. W.; Havlin, Shlomo; Ivanov, Plamen Ch. (2012). "Network physiology reveals relations between network topology and physiological function". Nature Communications. 3: 702. arXiv:1203.0242. Bibcode:2012NatCo...3..702B. doi:10.1038/ncomms1705. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 3518900. PMID 22426223.

- Automated analysis of the US presidential elections using Big Data and network analysis; S Sudhahar, GA Veltri, N Cristianini; Big Data & Society 2 (1), 1–28, 2015

- Network analysis of narrative content in large corpora; S Sudhahar, G De Fazio, R Franzosi, N Cristianini; Natural Language Engineering, 1–32, 2013

- Quantitative Narrative Analysis; Roberto Franzosi; Emory University © 2010

- Tsonis, Anastasios A.; Swanson, Kyle L.; Roebber, Paul J. (2006). "What Do Networks Have to Do with Climate?". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 87 (5): 585–595. Bibcode:2006BAMS...87..585T. doi:10.1175/BAMS-87-5-585. ISSN 0003-0007.

- Yamasaki, K.; Gozolchiani, A.; Havlin, S. (2008). "Climate Networks around the Globe are Significantly Affected by El Niño". Physical Review Letters. 100 (22): 228501. Bibcode:2008PhRvL.100v8501Y. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.228501. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 18643467.

- Boers, N.; Bookhagen, B.; Barbosa, H.M.J.; Marwan, N.; Kurths, J. (2014). "Prediction of extreme floods in the eastern Central Andes based on a complex networks approach". Nature Communications. 5: 5199. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.5199B. doi:10.1038/ncomms6199. ISSN 2041-1723. PMID 25310906.

- R. Cohen; S. Havlin (2010). Complex Networks: Structure, Robustness and Function. Cambridge University Press.

- A. Bunde; S. Havlin (1996). Fractals and Disordered Systems. Springer.

- Cohen, Reoven; Erez, K.; ben-Avraham, D.; Havlin, S. (2001). "Breakdown of the Internet under Intentional Attack". Physical Review Letters. 16 (86): 3682–5. arXiv:cond-mat/0010251. Bibcode:2001PhRvL..86.3682C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3682. PMID 11328053.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Callaway, Duncan S.; Newman, M. E. J.; Strogatz, S. H.; Watts, D. J (2000). "Network Robustness and Fragility: Percolation on Random Graphs". Physical Review Letters. 25 (85): 5468–71. arXiv:cond-mat/0007300. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..85.5468C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.5468. PMID 11136023.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- S. Shao, X. Huang, H.E. Stanley, S. Havlin (2015). "Percolation of localized attack on complex networks". New J. Phys. 17 (17): 023049.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Brunk, Nicholas E.; Lee, Lye Siang; Glazier, James A.; Butske, William; Zlotnick, Adam (2018). "Molecular jenga: The percolation phase transition (collapse) in virus capsids". Physical Biology. 15 (5): 056005. Bibcode:2018PhBio..15e6005B. doi:10.1088/1478-3975/aac194. PMC 6004236. PMID 29714713.

- Lee, Lye Siang; Brunk, Nicholas; Haywood, Daniel G.; Keifer, David; Pierson, Elizabeth; Kondylis, Panagiotis; Wang, Joseph Che-Yen; Jacobson, Stephen C.; Jarrold, Martin F.; Zlotnick, Adam (2017). "A molecular breadboard: Removal and replacement of subunits in a hepatitis B virus capsid". Protein Science. 26 (11): 2170–2180. doi:10.1002/pro.3265. PMC 5654856. PMID 28795465.

- Attardi, G.; S. Di Marco; D. Salvi (1998). "Categorization by Context" (PDF). Journal of Universal Computer Science. 4 (9): 719–736.

- Restrepo, Juan; E. Ott; B. R. Hunt (2006). "Characterizing the Dynamical Importance of Network Nodes and Links". Phys. Rev. Lett. 97 (9): 094102. arXiv:cond-mat/0606122. Bibcode:2006PhRvL..97i4102R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.094102. PMID 17026366.

- Carmi, S.; Havlin, S.; Kirkpatrick, S.; Shavitt, Y.; Shir, E. (2007). "A model of Internet topology using k-shell decomposition". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (27): 11150–11154. arXiv:cs/0607080. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10411150C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0701175104. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1896135. PMID 17586683.

- Marwan, N.; Donges, J.F.; Zou, Y.; Donner, R.V.; Kurths, J. (2009). "Complex network approach for recurrence analysis of time series". Physics Letters A. 373 (46): 4246–4254. arXiv:0907.3368. Bibcode:2009PhLA..373.4246M. doi:10.1016/j.physleta.2009.09.042. ISSN 0375-9601.

- Donner, R.V.; Heitzig, J.; Donges, J.F.; Zou, Y.; Marwan, N.; Kurths, J. (2011). "The Geometry of Chaotic Dynamics – A Complex Network Perspective". European Physical Journal B. 84 (4): 653–672. arXiv:1102.1853. Bibcode:2011EPJB...84..653D. doi:10.1140/epjb/e2011-10899-1. ISSN 1434-6036.

- Feldhoff, J.H.; Donner, R.V.; Donges, J.F.; Marwan, N.; Kurths, J. (2013). "Geometric signature of complex synchronisation scenarios". Europhysics Letters. 102 (3): 30007. arXiv:1301.0806. Bibcode:2013EL....10230007F. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/102/30007. ISSN 1286-4854.

- Newman, M., Barabási, A.-L., Watts, D.J. [eds.] (2006) The Structure and Dynamics of Networks. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Y. Chen, G. Paul, S. Havlin, F. Liljeros, H.E. Stanley (2008). "Finding a Better Immunization Strategy". Physical Review Letters (101): 058701.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- R. Cohen, S. Havlin, D. Ben-Avraham (2003). "Efficient immunization strategies for computer networks and populations". Physical Review Letters. 25 (91): 247901.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- S. V. Buldyrev; R. Parshani; G. Paul; H. E. Stanley; S. Havlin (2010). "Catastrophic cascade of failures in interdependent networks". Nature. 464 (7291): 1025–28. arXiv:0907.1182. Bibcode:2010Natur.464.1025B. doi:10.1038/nature08932. PMID 20393559.

- Jianxi Gao; Sergey V. Buldyrev; Shlomo Havlin; H. Eugene Stanley (2011). "Robustness of a Network of Networks". Phys. Rev. Lett. 107 (19): 195701. arXiv:1010.5829. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.107s5701G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.195701. PMID 22181627.

Books

- S.N. Dorogovtsev and J.F.F. Mendes, Evolution of Networks: from biological networks to the Internet and WWW, Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-19-851590-1

- G. Caldarelli, "Scale-Free Networks", Oxford University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-19-921151-7

- A. Barrat, M. Barthelemy, A. Vespignani, "Dynamical Processes on Complex Networks", Cambridge University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0521879507

- E. Estrada, "The Structure of Complex Networks: Theory and Applications", Oxford University Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0-199-59175-6

- K. Soramaki and S. Cook, "Network Theory and Financial Risk", Risk Books, 2016 ISBN 978-1782722199

- V. Latora, V. Nicosia, G. Russo, "Complex Networks: Principles, Methods and Applications", Cambridge University Press, 2017, ISBN 978-1107103184

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Network theory |

- netwiki Scientific wiki dedicated to network theory

- New Network Theory International Conference on 'New Network Theory'

- Network Workbench: A Large-Scale Network Analysis, Modeling and Visualization Toolkit

- Optimization of the Large Network doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.20183.06565/6

- Network analysis of computer networks

- Network analysis of organizational networks

- Network analysis of terrorist networks

- Network analysis of a disease outbreak

- Link Analysis: An Information Science Approach (book)

- Connected: The Power of Six Degrees (documentary)

- Kitsak, M.; Gallos, L. K.; Havlin, S.; Liljeros, F.; Muchnik, L.; Stanley, H. E.; Makes, H.A. (2010). "Influential Spreaders in Networks". Nature Physics. 6 (11): 888. arXiv:1001.5285. Bibcode:2010NatPh...6..888K. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.366.2543. doi:10.1038/nphys1746.

- A short course on complex networks

- A course on complex network analysis by Albert-László Barabási

- The Journal of Network Theory in Finance

- Network theory in Operations Research from the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS)