Interdependent networks

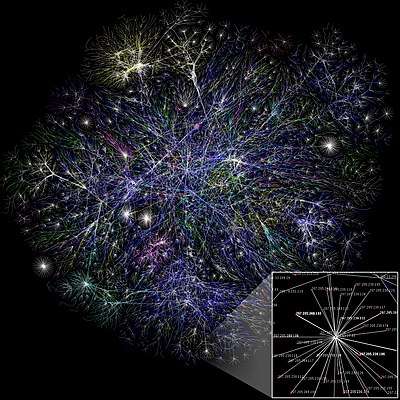

The study of interdependent networks is a subfield of network science dealing with phenomena caused by the interactions between complex networks. Though there may be a wide variety of interactions between networks, dependency focuses on the scenario in which the nodes in one network require support from nodes in another network.[1][2][3][4][5][6] For an example of infrastructure dependency see Fig. 1.

| Network science | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network types | ||||

| Graphs | ||||

|

||||

| Models | ||||

|

||||

| ||||

|

||||

Motivation for the model

In nature, networks rarely appear in isolation. They are typically elements in larger systems and can have non-trivial effects on one another. For example, infrastructure networks exhibit interdependency to a large degree. The power stations which form the nodes of the power grid require fuel delivered via a network of roads or pipes and are also controlled via the nodes of communications network. Though the transportation network does not depend on the power network to function, the communications network does. Thus the deactivation of a critical number of nodes in either the power network or the communication network can lead to a series of cascading failures across the system with potentially catastrophic repercussions. If the two networks were treated in isolation, this important feedback effect would not be seen and predictions of network robustness would be greatly overestimated.

Dependency links

Links in a standard network represent connectivity, providing information about how one node can be reached from another. Dependency links represent a need for support from one node to another. This relationship is often, though not necessarily, mutual and thus the links can be directed or undirected. Crucially, a node loses its ability to function as soon as the node it is dependent on ceases to function while it may not be so severely effected by losing a node it is connected to.

In percolation theory, a node is considered active as long as it is connected to the giant component. The introduction of dependency links adds another condition: that the node that it depends on is also active.

Dependency can be defined between different networks[1] and also within the same network.[7]

Percolation properties and phase transitions

Interdependent networks have markedly different percolation properties than single-networks.

If a single network is subjected to random attack , the largest connected component decreases continuously with a divergence of its derivative at the percolation threshold , a second-order phase transition. This result is established for ER networks, lattices and other standard topologies.

However, when multiple networks are interdependent, cascading failures emerge due to the positive feedback caused by dependency links. This family of processes causes a discontinuous or first order phase transition. This has been observed for random networks as well as lattices.[8] Furthermore, for embedded interdependent networks the transition is particularly precipitous without even a critical exponent for .[9]

Surprisingly, it has been shown that—contrary to the results for single networks—interdependent random networks with broader degree distributions are more vulnerable than those with narrow degree distributions. The high degree which is an asset in single networks can be a liability in interdependent networks. This is because the hubs which increase the robustness in single networks can be dependent on vulnerable low-degree nodes. The removal of the low-degree node then removes the hub and all of its links.[1][10]

Dynamics of cascading failure

A typical cascading failure in a system of interdependent networks can be described as follows:[1] We take two networks and with nodes and a given topology . Each node in relies on a critical resource provided by a node in and vice versa. If stops functioning, will also stop functioning and vice versa. The failure is triggered by the removal of a fraction of nodes from along with the links in which were attached to each of those nodes. Since every node in depends on a node in , this causes the removal of the same fraction of nodes in . In network theory, we assume that only nodes which are a part of the largest connected component can continue to function. Since the arrangement of links in and are different, they fragment into different sets of connected components. The smaller components in cease to function and when they do, they cause the same number of nodes (but in different locations) in to cease to function as well. This process continues iteratively between the two networks until no more nodes are removed. This process leads to a percolation phase transition at a value which is substantially larger than the value obtained for a single network.

Effect of network topology

In interdependent random networks in which a fraction of the nodes in one network are dependent on another, it is found that there is a critical value above which first-order phase transitions are possible.

In spatially embedded interdependent networks, a new kind of failure has been observed in which a relatively small failure can propagate through space and destroy an entire system of networks.[9]

Localized attacks

A new percolation process, localized attack was introduced by Berezin.[11] Localized attack is defined by removing a node, its neighbors and next nearest neighbors until a fraction of 1-p is removed. The critical (where the system collapse) for random networks was studied by Shao.[12] Surprisingly, for spatial interdependent networks there are cases in which a finite number (independent on the size of the system) of nodes causes cascading failures through the whole system and the system collapses. For this case =1. [13]

Recovery of nodes and links

The concept of recovery of elements in a network and its relation to percolation theory was introduced by Majdandzic.[14] In percolation it is usually assumed that nodes (or links) fail but in real life (e.g, infrastructure) nodes can also recover. Majdandzic et al introduced a percolation model with both failures and recovery and found new phenomena such as hysteresis and spontaneous recovery of systems. Later the concept of recovery was introduced to interdependent networks.[15] This study, besides finding rich and novel critical features, also developed a strategy to optimally repair a system of systems.

Comparison to many-particle systems in physics

In statistical physics, phase transitions can only appear in many particle systems. Though phase transitions are well known in network science, in single networks they are second order only. With the introduction of internetwork dependency, first order transitions emerge. This is a new phenomenon and one with profound implications for systems engineering. Where system dissolution takes place after steady (if steep) degradation for second order transitions, the existence of a first order transition implies that the system can go from a relatively healthy state to complete collapse with no advanced warning.

Reinforced nodes

In interdependent networks, it is usually assumed, based on percolation theory, that nodes become nonfunctional if they lose connection to the network giant component. However, in reality, some nodes, equipped with alternative resources, together with their connected neighbors can still be functioning after being disconnected from the giant component. Yuan et al[16] generalized percolation model that introduces a fraction of reinforced nodes in the interdependent networks that can function and support their neighborhood. The critical fraction of reinforced nodes needed to avoid catastrophic failures have been found.

Interdependence Dynamics

The original model of interdependent networks[1] regarded only structural dependencies, i.e., if a node in network A depends on a node in network B and this node in network B fails also the node in A fails. This lead to cascading failures and abrupt transitions. Danziger et al[17] studied the case where a node in one depends on the dynamic on the other network. For this, Danziger et al developed a dynamic dependency framework capturing interdependent between dynamic systems. They study synchronization and spreading processes in multilayer networks. Coupled collective phenomena, including multi-stability, hysteresis, regions of coexistence, and macroscopic chaos have been found.

Examples

- Infrastructure networks. The network of power stations depends on instructions from the communications network which require power themselves.[18]

- Transportation networks. The networks of airports and seaports are interdependent in that in a given city, the ability of that city's airport to function is dependent upon resources obtained from the seaport or vice versa.[19][20]

- Physiological networks. The nervous and cardiovascular system are each composed of many connected parts which can be represented as a network. In order to function, they require connectivity within their own network as well as resources available only from the other network.[21]

- Economic/financial networks. Availability of credit from the banking network and economic production by the network of commercial firms are interdependent. In October 2012, a bipartite network model of banks and bank assets was used to examine failure propagation in the economy at large.[22]

- Protein networks. A biological process regulated by a number of proteins is often represented as a network. Since the same proteins participate in different processes, the networks are interdependent.

- Ecological networks. Food webs constructed from species which depend on one another are interdependent when the same species participates in different webs.[23]

- Climate networks. Spatial measurements of different climatological variables define a network. The networks defined by different sets of variables are interdependent.[24]

See also

- Cascading failure

- 2003 Italy blackout

- Complex networks

- Network science

- Percolation theory

References

- Buldyrev, Sergey V.; Parshani, Roni; Paul, Gerald; Stanley, H. Eugene; Havlin, Shlomo (2010). "Catastrophic cascade of failures in interdependent networks". Nature. 464 (7291): 1025–1028. arXiv:1012.0206. Bibcode:2010Natur.464.1025B. doi:10.1038/nature08932. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 20393559.

- Vespignani, Alessandro (2010). "Complex networks: The fragility of interdependency". Nature. 464 (7291): 984–985. Bibcode:2010Natur.464..984V. doi:10.1038/464984a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 20393545.

- Gao, Jianxi; Buldyrev, Sergey V.; Stanley, H. Eugene; Havlin, Shlomo (2011). "Networks formed from interdependent networks". Nature Physics. 8 (1): 40–48. Bibcode:2012NatPh...8...40G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.379.8214. doi:10.1038/nphys2180. ISSN 1745-2473.

- Kenett, Dror Y.; Gao, Jianxi; Huang, Xuqing; Shao, Shuai; Vodenska, Irena; Buldyrev, Sergey V.; Paul, Gerald; Stanley, H. Eugene; Havlin, Shlomo (2014). "Network of Interdependent Networks: Overview of Theory and Applications". In D'Agostino, Gregorio; Scala, Antonio (eds.). Networks of Networks: The Last Frontier of Complexity. Understanding Complex Systems. Springer International Publishing. pp. 3–36. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-03518-5_1. ISBN 978-3-319-03517-8.

- Danziger, Michael M.; Bashan, Amir; Berezin, Yehiel; Shekhtman, Louis M.; Havlin, Shlomo (2014). An Introduction to Interdependent Networks. 22nd International Conference, NDES 2014, Albena, Bulgaria, July 4–6, 2014. Proceedings. Communications in Computer and Information Science. 438. pp. 189–202. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-08672-9_24. ISBN 978-3-319-08671-2.

- Kivelä, Mikko; Arenas, Alex; Barthelemy, Marc; Gleeson, James P.; Moreno, Yamir; Porter, Mason A. (2014). "Multilayer networks". Journal of Complex Networks. 2 (3): 203–271. arXiv:1309.7233. doi:10.1093/comnet/cnu016. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- Parshani, R.; Buldyrev, S. V.; Havlin, S. (2010). "Critical effect of dependency groups on the function of networks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (3): 1007–1010. arXiv:1010.4498. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.1007P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1008404108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3024657. PMID 21191103.

- Parshani, Roni; Buldyrev, Sergey V.; Havlin, Shlomo (2010). "Interdependent Networks: Reducing the Coupling Strength Leads to a Change from a First to Second Order Percolation Transition". Physical Review Letters. 105 (4): 48701. arXiv:1004.3989. Bibcode:2010PhRvL.105d8701P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.048701. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 20867893.

- Li, Wei; Bashan, Amir; Buldyrev, Sergey V.; Stanley, H. Eugene; Havlin, Shlomo (2012). "Cascading Failures in Interdependent Lattice Networks: The Critical Role of the Length of Dependency Links". Physical Review Letters. 108 (22): 228702. arXiv:1206.0224. Bibcode:2012PhRvL.108v8702L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.228702. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 23003664.

- Gao, Jianxi; Buldyrev, Sergey V.; Havlin, Shlomo; Stanley, H. Eugene (2011). "Robustness of a Network of Networks". Physical Review Letters. 107 (19): 195701. arXiv:1010.5829. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.107s5701G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.195701. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 22181627.

- Berezin, Yehiel; Bashan, Amir; Danziger, Michael M.; Li, Daqing; Havlin, Shlomo (2015). "Localized attacks on spatially embedded networks with dependencies". Scientific Reports. 5 (1): 8934. Bibcode:2015NatSR...5E8934B. doi:10.1038/srep08934. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4355725. PMID 25757572.

- Shao, Shuai; Huang, Xuqing; Stanley, H Eugene; Havlin, Shlomo (2015). "Percolation of localized attack on complex networks". New Journal of Physics. 17 (2): 023049. arXiv:1412.3124. Bibcode:2015NJPh...17b3049S. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/17/2/023049. ISSN 1367-2630.

- D Vaknin, MM Danziger, S Havlin (2017). "Spreading of localized attacks in spatial multiplex networks". New J. Phys. (19): 073037.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Majdandzic, Antonio; Podobnik, Boris; Buldyrev, Sergey V.; Kenett, Dror Y.; Havlin, Shlomo; Eugene Stanley, H. (2013). "Spontaneous recovery in dynamical networks". Nature Physics. 10 (1): 34–38. Bibcode:2014NatPh..10...34M. doi:10.1038/nphys2819. ISSN 1745-2473.

- Majdandzic, Antonio; Braunstein, Lidia A.; Curme, Chester; Vodenska, Irena; Levy-Carciente, Sary; Eugene Stanley, H.; Havlin, Shlomo (2016). "Multiple tipping points and optimal repairing in interacting networks". Nature Communications. 7: 10850. arXiv:1502.00244. Bibcode:2016NatCo...710850M. doi:10.1038/ncomms10850. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4773515. PMID 26926803.

- Yuan, X.; Hu, Y.; Stanley, H.E.; Havlin, S. (2017). "Eradicating catastrophic collapse in interdependent networks via reinforced nodes". PNAS. 114 (13): 3311. arXiv:1605.04217. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114.3311Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.1621369114. PMC 5380073. PMID 28289204.

- Danziger, Michael M; Bonamassa, Ivan; Boccaletti, Stefano; Havlin, Shlomo (2019). "Dynamic interdependence and competition in multilayer networks". Nature Physics. 15 (2): 178. arXiv:1705.00241. doi:10.1038/s41567-018-0343-1.

- Rinaldi, S.M.; Peerenboom, J.P.; Kelly, T.K. (2001). "Identifying, understanding, and analyzing critical infrastructure interdependencies". IEEE Control Systems Magazine. 21 (6): 11–25. doi:10.1109/37.969131. ISSN 0272-1708.

- Parshani, R.; Rozenblat, C.; Ietri, D.; Ducruet, C.; Havlin, S. (2010). "Inter-similarity between coupled networks". EPL. 92 (6): 68002. arXiv:1010.4506. Bibcode:2010EL.....9268002P. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/92/68002. ISSN 0295-5075.

- Gu, Chang-Gui; Zou, Sheng-Rong; Xu, Xiu-Lian; Qu, Yan-Qing; Jiang, Yu-Mei; He, Da Ren; Liu, Hong-Kun; Zhou, Tao (2011). "Onset of cooperation between layered networks" (PDF). Physical Review E. 84 (2): 026101. Bibcode:2011PhRvE..84b6101G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.84.026101. ISSN 1539-3755. PMID 21929058.

- Bashan, Amir; Bartsch, Ronny P.; Kantelhardt, Jan. W.; Havlin, Shlomo; Ivanov, Plamen Ch. (2012). "Network physiology reveals relations between network topology and physiological function". Nature Communications. 3: 702. arXiv:1203.0242. Bibcode:2012NatCo...3E.702B. doi:10.1038/ncomms1705. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 3518900. PMID 22426223.

- Huang, Xuqing; Vodenska, Irena; Havlin, Shlomo; Stanley, H. Eugene (2013). "Cascading Failures in Bi-partite Graphs: Model for Systemic Risk Propagation". Scientific Reports. 3: 1219. arXiv:1210.4973. Bibcode:2013NatSR...3E1219H. doi:10.1038/srep01219. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 3564037. PMID 23386974.

- Pocock, M. J. O.; Evans, D. M.; Memmott, J. (2012). "The Robustness and Restoration of a Network of Ecological Networks" (PDF). Science. 335 (6071): 973–977. Bibcode:2012Sci...335..973P. doi:10.1126/science.1214915. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 22363009.

- Donges, J. F.; Schultz, H. C. H.; Marwan, N.; Zou, Y.; Kurths, J. (2011). "Investigating the topology of interacting networks". The European Physical Journal B. 84 (4): 635–651. arXiv:1102.3067. Bibcode:2011EPJB...84..635D. doi:10.1140/epjb/e2011-10795-8. ISSN 1434-6028.